The strongly Surrealist Skeleton Dress was designed by Elsa Schiaparelli in collaboration with Salvador Dalí for her 1938 collection Le Cirque.

About the Look

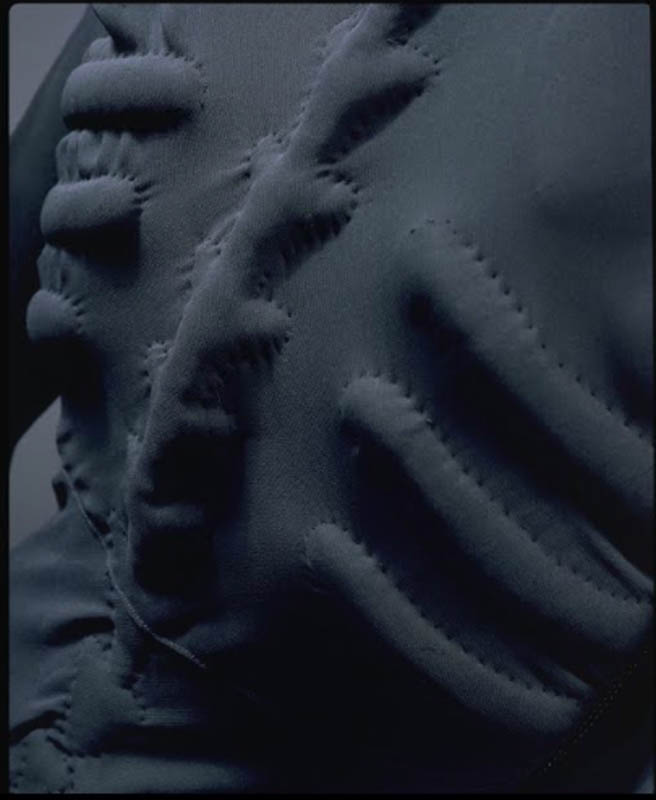

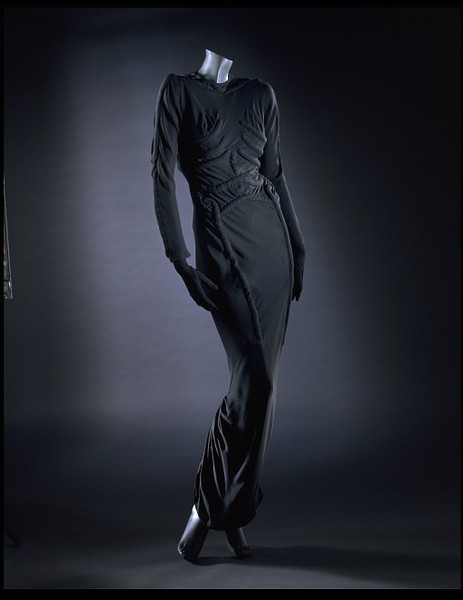

The floor-length, black body-hugging evening gown is composed of silk crêpe with a fine matte sheen (Fig. 1/ V&A). The gown covers the wearer from her fingertips to her ankles, utilizing a high neckline, and plastic zippers on the shoulder seams and right side (V&A). The full-coverage aspect of the garment, along with its seemingly constricting nature, plays into the surrealism of the garment, acting as a “second skin” on the wearer (V&A). The Skeleton Dress features quilting resembling large bones, particularly the rib cage, vertebrae, hip, and leg bones. The skeletal structure is made using an exaggerated trapunto quilting technique involving the use of cotton wadding to give the design a three-dimensional effect (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Skeleton dress, 1938. Silk, cotton. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.394&A-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: V&A

Fig. 2 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Skeleton dress, 1938. Silk, cotton. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.394&A-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: V&A

Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Skeleton dress, 1938. Silk, cotton. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.394&A-1974. Given by Miss Ruth Ford. Source: V&A

About the context

The year 1938 was a particularly turbulent one in the world; the United States was still reeling from the Great Depression and WWII was on the horizon in Europe (Shim). There was a mutual feeling of somberness that led to a yearning for escapism, as can be seen in Hollywood films of the era. The 1930s marked the beginning of the “Golden Age of Hollywood;” glamorous actresses, suave actors, and giant studios produced fantastical films and a growing celebrity culture. A rising fashion icon of the time was the American Wallace Simpson, who famously became Duchess of Windsor and was known for her sophisticated yet free-spirited style. She appreciated Schiaparelli’s aesthetic and was a loyal customer, thus she was often photographed wearing the couturier’s designs (Shim). The dress features the simple, sophisticated silhouette with slightly broad shoulders, popular throughout most of the 1930s. The quirky surrealist themes of Schiaparelli’s design was also on trend (Shim).

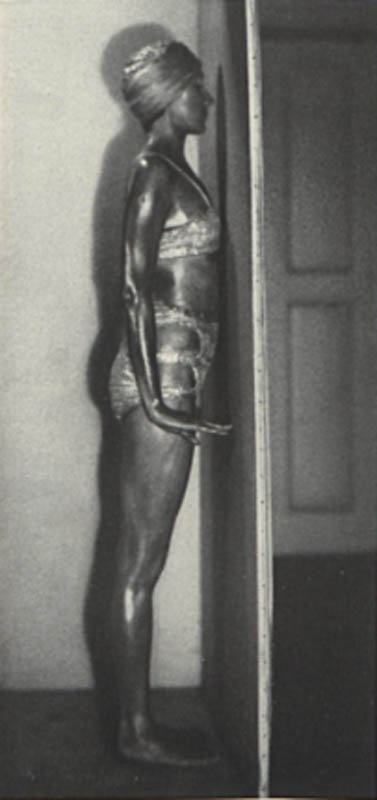

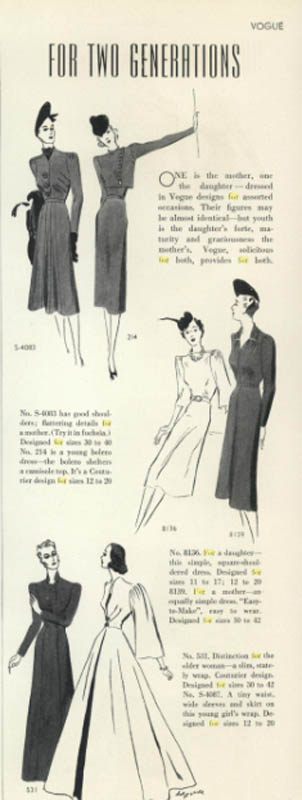

The ideal body of the 1930s was slightly less boyish and youthful than that of the 1920s – favoring subtle curves, high waistlines, long and elegant posture (Fig. 3/ “Features: Good Form” 82). The Skeleton Dress fit perfectly into the ideal silhouette of the 1930s, but by 1938, the year the Skeleton Dress debuted, there was already talk of a changing silhouette for the 1940s – the hourglass body ideal began to dominate almost a decade before Dior’s 1947 New Look (Fig. 4/ Shim).

Fig. 3 - Marguerite Agniel (American, 1891-19??). "Features: Good Form in Figures" Vogue, vol. 75 iss. 4 (February 1930). Source: Vogue Archive

Fig. 4 - Illustrator unknown. "Fashion: For Two Generations" Vogue, vol. 92, iss. 5 (September 1938). Source: Vogue Archive

Schiaparelli was born into a family of aristocrats, descended from the Medici family, and originally studied philosophy, although she had aspirations of becoming an actor (Hoyningen-Huene). She met her first husband, Count Wilhelm Wendt de Kerlor, while he was speaking at a theology conference. They moved to New York City and had a daughter, known by her nickname, Gogo (Hoyningen-Huene). She divorced Wilhelm, moved to Paris, and moved in artistic circles (Hoyningen-Huene). She met couturier Paul Poiret, who allowed Schiaparelli to take home several garments which apparently inspired her to become a designer (Hoyningen-Huene).

Schiaparelli began freelance designing, gaining widespread recognition when she designed a knit pullover with a white trompe-l’œl bow motif, which was noted as a “masterpiece” by Vogue (Hoyningen-Huene). She officially opened her own Couture House in 1927, first specializing in sportswear with the words “Schiaparelli – Pour le Sport” on the door plate (Hoyningen-Huene). She uniquely combined sportswear and haute couture, which gave her so much notoriety that she was the first female fashion designer to be featured on the cover of a magazine in the United States, TIME Magazine, in 1934 (Fig. 5). The combination of eclectic family and friends, her travels, the inspiration from Poiret, and her own fearless way of creating had a notable effect on the Schiaparelli Couture House aesthetic. As she herself was a fashion visionary in so many ways, it only made sense that she worked with art world visionaries like Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau.

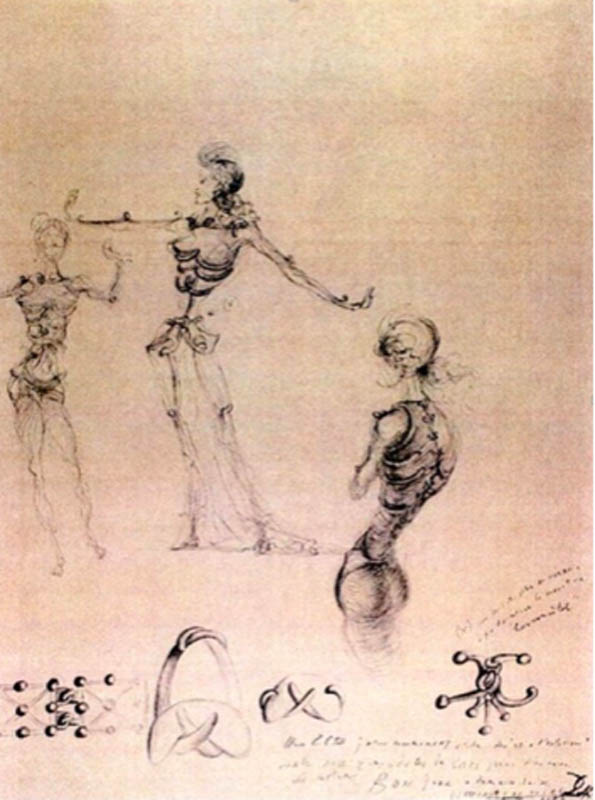

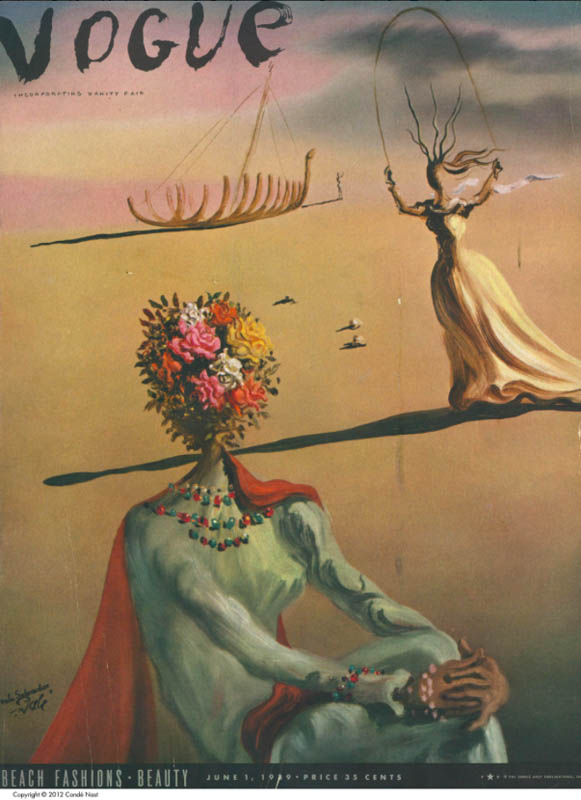

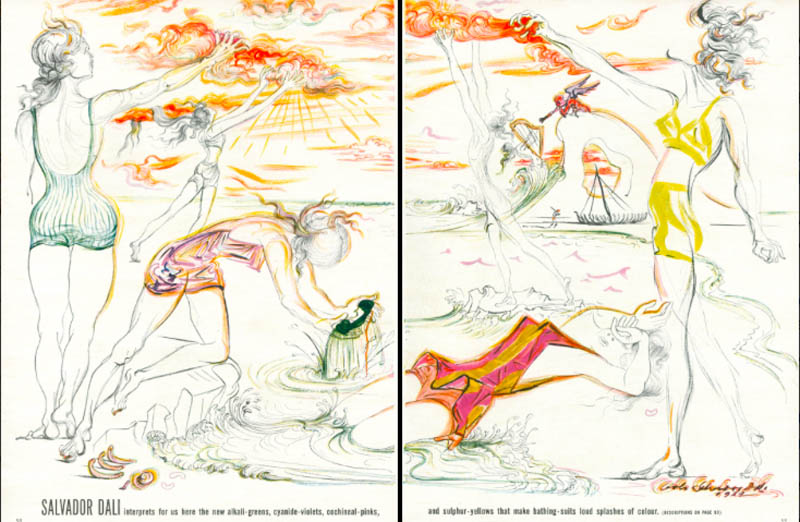

Schiaparelli utilized surrealist influences throughout her work as a couturier. The Le Cirque collection (1938), inspired by the circus, featured many whimsical and light-hearted circus-themed elements which made the gothic qualities of the Skeleton Dress look odd in comparison (“Schiaparelli & the Artists”). Dalí provided the inspiration that led to the collaboration on the Skeleton Dress by giving Schiaparelli a drawing of a woman in a sheer, body-hugging dress, but with her rib cage and hip bones exposed (Fig. 6/ Cain). He attached a note that said, “Dear Elsa, I like this idea of ‘bones on the outside’ enormously…” (“Schiaparelli & the Artists”). Dalí often utilized human figures in his own art, which featured warped limbs and proportions, usually drawn very tall (Figs. 7, 8).

The garment is emblematic of the Schiaparelli Couture House because it so flawlessly fits within her aesthetic; avant-garde, yet classic in terms of construction and silhouette. Elsa herself said “I believe in a strict neatness about both day and evening clothes, their simple lines accentuated by an original touch” (Woolf 69). The Skeleton Dress was widely reflective of this principle of hers, exemplifying her signature pencil silhouette as well as her eccentric additions (“Fashion: Paris Presents” 114). Both Dalí and Schiaparelli enjoyed shocking consumers, and both were willing to step outside of what societal norms were for the sake of art, making the collaboration fit seamlessly in both of their respective portfolios (Rubenstein).

The Skeleton Dress evokes Schiaparelli’s specialty, sportswear, due to the fabric it was made out of and the level of mobility the dress allows for. Schiaparelli designed with eccentricity and ingenuity at the forefront, but with an emphasis on practicality and comfort, posing the question: “When will women learn that it is better to be smart than fashionable and that smartness makes fashion?” (Woolf 69). The Skeleton dress combines avante-garde artistic elements not only with elegance, but also wearability.

Fig. 5 - Photographer unknown. Time Magazine Cover, vol. 24 iss. 7 (August 1934). Source: Maison Schiaparelli

Fig. 6 - Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989). The Skeleton Woman, 1938. Source: Maison Schiaparelli

Fig. 7 - Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989). Vogue Magazine Cover, vol. 93 iss. 11 (June 1939). Source: Vogue Archive

Fig. 8 - Salvador Dalí (Spanish, 1904-1989). "Fashion: Salvador Dali Interprets For Us Here", Vogue, vol. 93 iss. 11 (June 1939). Source: Vogue Archive

In 1931 Vogue summed up Schiaparelli’s impact in fashion when they wrote:

“[Schiaparelli] made a bold attack on fabrics. The conventions of cut held no restraint for her, rather were they something to be ignored in her avoidance to the banal… the result was smart, unusual, individual clothes that have a practical side as well, and no stigma of eccentricity.” (“Variety: The House of Schiaparelli” 48)

The Skeleton Dress is one of Schiaparelli’s most important garments because it shows the bones of Schiaparelli as a designer. At her core, she designed garments with clean tailoring and silhouettes for the modern women, but with her own particularly zesty flair.

Its Afterlife

The Skeleton Dress inspired the “Spine Corset,” designed by Shaun Leane for Alexander McQueen in the Spring/Summer 1998 collection (Fig. 9/ “Spine Corset”). Made out of aluminum and leather, the corset features a rib cage and vertebrae, and was cast using an actual human skeleton (“Spine Corset”). The piece was shown on top of a shimmering black dress, specifically nodding to Schiaparelli’s influence in the design of the corset (Fig. 10).

The Victoria and Albert Museum showcased the Skeleton Dress in their 2007 “Surreal Things” exhibition that particularly emphasized surreal artists crossing over into fashion. Alexander Klar, the assistant curator of the show, commented that the body and dressing of the body are really intertwined for surrealists (Jones 9). Surrealist artists reveled in “promot[ing] the conflict between the bohemian and the bourgeoisie in fashion,” and Schiaparelli and Dalí met in the middle of that conflict, making the Skeleton Dress a perfect reflection of the surreal aspects of fashion and of our own bodies (Jones 9).

Most recently, Maison Schiaparelli introduced their 2020 Spring-Summer haute couture collection which featured a tribute to the 1938 Skeleton Dress (Fig. 11). The floor-length dress, made of black silk crepe, featured spaghetti straps, open décolletage with mesh fabric in the center, and embroideries highlighting the rib cage, hip, and leg bones, as well as on the arms (“Haute Couture Printemps-Été 2020”). Maison Schiaparelli also paid tribute to the Skeleton Dress in their ready-to-wear 2020/21 collection, featuring a strapless, straight tea-length dress including less-emphasized and more abstract embroidered boning as well as surrealist buttons down the front of the dress (Fig. 12).

Fig. 9 - Shaun Leane for Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-). 'Spine' corset, Spring/Summer 1998. Aluminium and leather. London: Victoria and Albert. Source: V&A

Fig. 10 - Shaun Leane for Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-). 'Spine' corset, Spring/Summer 1998. Aluminium and leather. London: Victoria and Albert. Source: V&A

Fig. 11 - Schiaparelli (Italian, 2012-). Look 19, Spring/Summer 2020. Source: Vogue Runway

Fig. 12 - Schiaparelli (Italian, 2012-). Jeweled Skeleton Column dress, Autumn Winter 2020-2021. Source: Schiaparelli

References:

- Cain, Abigail. “The Fashion Designer Who Made Dalí’s Art Wearable.” Artsy. December 7, 2017. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-fashion-designer-made-dalis-art-wearable.

- “Corsets & Brassieres: Schiaparelli Sees Need for Light but Strong Foundations.” Women’s Wear Daily, Dec 02, 1937, 17. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1700006600?accountid=27253.

- “Fashion: Paris Presents: Schiaparelli’s Formfit Foundations.” Vogue, Mar 15, 1940, 114. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/904283837?accountid=27253.

- Hevesi, Dennis. “Ruth Ford, Film and Stage Actress, Dies at 98.” The New York Times, August 14, 2009. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/14/theater/14ford-1.html.

- Hoyningen-Huene, George. “The Life of Elsa Schiaparelli.” Schiaparelli. Maison Schiaparelli, 2020. https://www.schiaparelli.com/en/21-place-vendome/the-life-of-elsa/.

- Jones, Nina. 2007. “Ready-to-Wear Report: Surrealists Get into Fashion at the V&A.” WWD, Apr 03, 2007, 9. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1434311125?accountid=27253.

- Paris Personalities.” Good Housekeeping, 1938, 06, 112-113, 196. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1858678750?accountid=27253.

- Rubenstein, Celestial. “1937 – Elsa Schiaparelli, Lobster Dinner Dress.” Fashion History Timeline. Fashion Institute of Technology, January 13, 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1937-schiaparelli-lobster/.

- “Schiaparelli & the Artists – Salvador Dali.” Maison Schiaparelli. 2016. https://www.schiaparelli.com/en/21-place-vendome/schiaparelli-and-the-artists/salvador-dali/schiaparelli-skeleton-dress/.

- Shim, Gun Woo. “1938.” Fashion History Timeline. Fashion Institute of Technology, August 5, 2019. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1938-2/.

- S.J. Woolf. “Fashion Hunt With Schiaparelli: A Designer Looks At Us And Asks For Simplicity.” New York Times, Dec 24, 1939. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/102896436?accountid=27253.

- “The Skeleton Dress – Elsa Schiaparelli.” Google Arts & Culture. 2020. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/TgE-2RRZILJYqQ?childAssetId=mwHmW4qMRNu9lg.

- “The Skeleton Dress: Elsa Schiaparelli.” Victoria and Albert Museum. 2020. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O65687/the-skeleton-dress-evening-dress-elsa-schiaparelli/.

- “Spine Corset.” The Museum of Savage Beauty. Victoria and Albert Museum, 2020. https://www.vam.ac.uk/museumofsavagebeauty/mcq/spine-corset/.

- “Variety: The House of Schiaparelli.” Vogue, Apr 15, 1931, 48, 140. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879187184?accountid=27253.