The Women (1939)

Synopsis

Trusting Park Avenue socialite Mary Haines (Norma Shearer) loses her husband to scheming shopgirl Crystal Allen (Joan Crawford), and can only win him back if she becomes as cunning as her so-called friends.

Directed by

George Cukor

Release date

1 September 1939

Costume Designer

Adrian

Studio

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Source: IMDb

Film trailer – The Women (1939)

The Opposite Sex (1956)

Synopsis

Former radio singer Kay Hilliard (June Allyson) learns from her gossipy friends that her husband is having an affair with chorus girl Crystal Allen (Joan Collins). Devastated, she breaks down and goes to Reno to file for divorce. However, when she hears that gold-digging Crystal is making him unhappy, Kay resolves to get her husband back.

Directed by

David Miller

Release date

26 October 1956

Costume Designer

Helen Rose

Studio

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Source: IMDb

Film trailer – The Opposite Sex (1956)

Introduction

W

hen The Women opened on Broadway in 1936, audiences were treated to an acerbic commentary on the lives of Manhattan’s wealthiest socialites, penned “in venom” by playwright Clare Boothe (Nugent, 32). Filled with feline wit and unbridled malice, the comedy of manners was a smash hit with audiences and played 666 performances in its triumphant run at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre (American Film Institute). Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer purchased the rights to make a film adaptation, using their illustrious roster of contract players to create an all-star, all-female cast. Writers Anita Loos and Jane Murfin adapted the script for the screen, which told the story of a trusting Park Avenue socialite who loses her husband to a scheming shop girl, thanks to the “terrible collection of women” she calls her friends. Moviegoers relished in seeing their favorite stars go on “a glorious cat-clawing rampage,” and The Women was praised as an amusing “sociological investigation of the scalpel-tongued Park Avenue set” (Nugent, 32). The film would be remade as a Technicolor musical by the same studio in 1956, this time with the title —and actors of—The Opposite Sex. Since then, the fiendish comedy has enjoyed reincarnations on both stage and screen, with a Broadway revival in 2001 and a modern film adaptation in 2008. While these recent efforts have failed to garner the same critical acclaim as their original 1930s counterparts, the piece has garnered enduring appeal—due, in part, to “the rowdy spectacle of ladies being anything but ladylike” (Brantley, New York Times). The legacy of Clare Boothe’s work, however, rests heavily on the original 1939 film, which has since acted as the esteemed touchstone for all later iterations of the deliciously poisonous piece.

Film Analysis: The Women (1939)

Overview

T

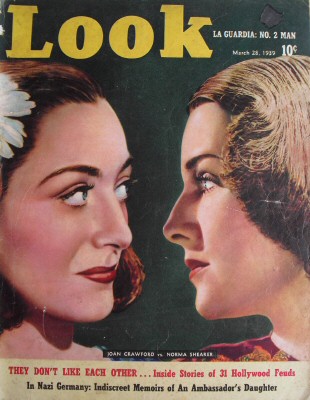

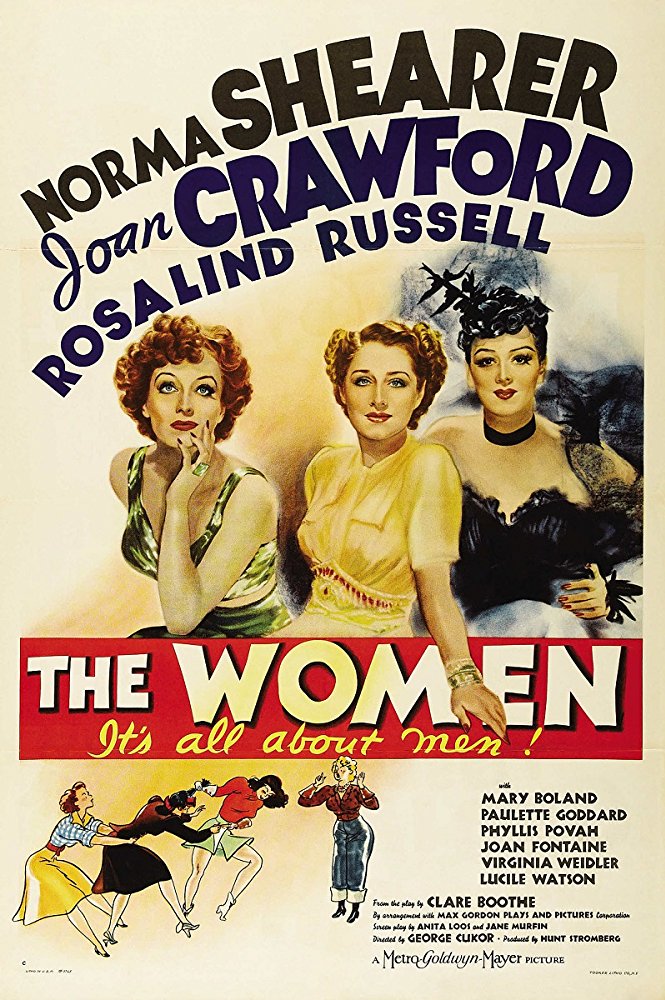

he first film adaptation of The Women boasted an all-star cast that could only come from MGM (fig. 1)—with Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, and Rosalind Russell leading an ensemble that also included Joan Fontaine, Paulette Goddard, Mary Boland, and Phyllis Povah, who reprised her Broadway role (American Film Institute). The Women was officially released on September 1, 1939 and received a glamorous premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre (fig. 2), where 15,000 onlookers lined Hollywood Boulevard hoping to set eyes on the parade of stars (Kendall, Los Angeles Times).

Fig. 1 - A studio publicity photograph featuring the star-studded cast. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Turner Classic Movies

Fig. 2 - 1939 The film's premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on August 31. The Women, 1939. Source: Los Angeles Times

Fig. 3 - Adrian's sketches for "The Women" featured in a movie magazine's fashion section. Photoplay Magazine, September 1939. Source: Media History Digital Library

The film opened to critical acclaim, and its stars delivered career-changing performances under the direction of George Cukor. The screen adaptation of the Broadway play had a significant focus on fashion, due in part to the elaborate creations of MGM costume designer, Adrian. However, the most noteworthy aspect of the picture—the Technicolor fashion show which featured designs by Adrian and thirty-five models from the New York World’s Fair—received universal scorn from film critics (Gutner, 176). In his New York Times review, Frank S. Nugent wrote that the “style show in Technicolor which may be lovely—at least that’s what most of the women around us seemed to think” had “no place in the picture,” and was “the only mark against George Cukor’s otherwise shrewd and sentient direction” (Nugent, 32). Despite this criticism, Adrian’s costume parade was adored by the fashion press. Women’s Wear Daily dutifully covered his designs for the leading actresses (fig. 3), but eagerly discussed the clothing featured in the Technicolor fashion show with the same, if not greater, emphasis. The retail industry also delighted in the film’s focus on fashion. Department stores used the film’s premiere as a marketing opportunity, running concurrent ads that featured stills from the movie and such text: “Macy’s salutes a great film and a great gender…depend on us to bring you practical clothes inspired by the most glamorous picture of the year” (The Women Makes Promotion Headline, 32). That season, Macy’s Cinema Shops offered fashion-minded moviegoers the opportunity to purchase adaptations of four evening gowns, one daytime ensemble, three hats, and a negligee from the hit film (Gutner, 182).

About the Costume Designer: Adrian

The renowned head designer at MGM was born Adrian Adolph Greenberg on March 3, 1903 in Naugatuck, Connecticut. He grew up around his parents’ hat shop, which gave him “a keen awareness of fashion and the manufacturing process” (Jorgensen and Scoggins, 134). He began his design career on Broadway, collaborating with the likes of Irving Berlin on extravagant musical revues. He worked for several years under contract at DeMille Pictures Corporation, and followed DeMille to MGM in 1928—where he would build a career as one of the industry’s most prolific designers, costuming over 260 films during his lifetime (Jorgensen and Scoggins, 147). During his tenure at MGM, he established working relationships with the studio’s greatest stars and played an important role in shaping their star personas. This was especially true in the case of Joan Crawford (fig. 4), a true rags-to-riches example of a studio-manufactured star, who made her rise in Hollywood while wearing some of Adrian’s most memorable creations. Actress and designer would prove instrumental in each other’s success at MGM—most notably, in their collaboration on the film Letty Lynton (1931), which featured a white organdy dress that would send them both skyrocketing to fashion fame (fig. 5). In 1938, Adrian showcased his talent for designing historical costumes in the lavish Marie Antoinette, starring Norma Shearer in the title role. Before reteaming with both actresses on The Women in 1939, he stunned the world with his fantastical designs for The Wizard of Oz. He married actress Janet Gaynor the same year, and they later jointly financed a new couture business on Wilshire Boulevard in Beverly Hills (Jorgensen and Scoggins, 146).

Fig. 4 - Costume designer Adrian looks over a sketch with actress Joan Crawford. The Women, 1939. Source: "Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years, 1928–1941" by Howard Gutner

Fig. 5 - Joan Crawford modeling a white organdy dress designed by Adrian. Letty Lynton, 1932. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: IMDb

After he left MGM in 1941, his clothes still often appeared on screen—purchased either from his couture house or from his ready-to-wear line, “Adrian Originals,” based on Seventh Avenue in New York. He would go on to run a successful business for ten years, until he was forced to retire following a heart attack in 1952. Adrian returned to MGM early the same year to design his final film, Lovely to Look At. He died in 1959, and left behind a legacy as one of film’s greatest costume designers—instrumental in creating the unmistakable flavor of glamour of Hollywood’s golden age.

Costume and Production Design

Though based on a society rooted in a specific time and place, The Women resides in a fantasy world where all clothes are Adrian-designed, and all interiors exist to complement them. Under the art direction of Cedric Gibbons, the film brings to life a luxurious playground for the idle rich. The opening scene takes place at Sydney’s, a palatial beauty salon whose reception area more closely resembles the deck of ocean liner—with its sweeping modernist staircase, geometric floor designs, and idyllic outdoor vista painted on the back wall (fig. 6). The production design of the film was not only a visual treat for the moviegoers of 1939, but also a valuable resource to present-day fashion historians, for “the bright light it sheds on the exclusive retail industry, from fanciful fashion show to the beauty salon” (“Fashion Significances,” 4).

Fig. 6 - The scene of gossip-ridden manicures Sydney’s. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Art direction by Cedric Gibbons, set decoration by Edwin B. Willis and Jack D. Moore. Source: Author

Fig. 7 - Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, and Rosalind Russell in a studio publicity photograph. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: IMDb

The stylized sets were populated by a cast of 135 women (plus female dogs and monkeys), for whom Adrian designed a staggering 237 costumes (Vieira, 127). Because of the nature of the piece and the sheer number of characters that needed to remain distinctive from one another, “each actress had to be dressed to type and sometimes exaggerated to make the point more forceful” (“Adrian Clothes for The Women,” 3). In his designs, Adrian adeptly uses clothing to communicate the characteristics of each player, creating visual foils and complements for each woman on the screen. The true genius of his work lies in his skillful treatment of contemporary trends in a way that serves both the individual characters and the production as a whole. While some of his more imaginative designs may border on fashion fantasy, the clothes shown in the film never crossed into the realms of costume or camp; what resulted was a meticulously crafted spectacle that acted as a platform for real-life designs that felt current and distantly attainable. To the delight of fashion journalists, “the costuming was up to the minute with fitted waistlines, flared skirts, front fullness in evening skirts, bustles, little hats, the very high crowned visor hat, tiered evening skirts” (“Adrian Clothes for The Women,” 32). Chief among the most enviable designs in The Women were those worn by the film’s three stars whose names appeared above the title. Adrian created costumes for Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, and Rosalind Russell under three distinctive design philosophies which served their characters—each unique, yet glamorous all (fig. 7).

Character Costume Analysis

Mary Haines (played by Norma Shearer)

N

orma Shearer, the reigning queen of the MGM lot, played the leading role of Mary Haines—the virtuous protagonist who discovers she has been living in a fool’s paradise upon learning of her husband’s affair with a conniving shop girl. As a devoted wife and mother, her style is considerably less ostentatious in comparison to her catty counterparts. While the other Park Avenue matrons swathe themselves in flamboyant fashions that seem to evince their dubious morality, the wholesome Mary Haines is mostly outfitted in sensible suits. The defining essence of Adrian’s designs for Norma Shearer’s character is verbalized early in the film, when her daughter helps her dress for a luncheon with her friends, saying, “Mother, let me pick out your dress for you. They’ll all be so fancy…why don’t you be plain?” In the case of selling the film’s fashions to eager moviegoers, “plain” actually translates to “wearable”—with the costumes worn by Norma Shearer inspiring the bulk of the collection for sale in Macy’s Cinema Shops (Gutner, 184).

Fig. 8 - Norma Shearer as Mary Haines. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Author

Fig. 9 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Women's suit, 1948. Wool. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.432.5a–c. Gift of Joseph S. Simms, 1979. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Despite the understated nature of Mary Haines’s wardrobe, her clothes remain aspirational in the details of their construction, which effectively communicate the subtle essence of luxury. In one scene, she wears a tailored jacket constructed of curvilinear panels that create an elegant gradient from shoulder to waistline, and mirrored from sleeve cap to wrist (fig. 8). This color-block technique would reappear in Adrian’s later designs for his personal label (fig. 9), and such meticulous piecework would become a hallmark of his tailored designs in his off-screen career. When designing for film, even his most austere designs are subjected to the camera’s desire for glamour—as is the case with the dark suit that Mary Haines wears to the fashion show. The otherwise sober ensemble is dressed up for the occasion with dynamic, screen-worthy accessories (fig. 10). She wears a jaunty light-colored hat trimmed with a net veil and an emphatic turkey feather. On her lapel is a large, jeweled brooch—a touch of sparkle for the film’s most glamorous scene.

Fig. 10 - Norma Shearer as Mary Haines. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Author

Another tailored ensemble worn by Norma Shearer in The Women (fig. 11) was featured in a “News About Suits” fashion spread in Photoplay: a bright blue woolen suit with “a short, cutaway jacket that is collarless with a small rolled reverse—the youthful collar of the white piqué waistcoat blouse finishes the neckline. The bias skirt has four flared gores” (Photoplay Fashions, 49). Designs such as this one “prefigured many of the ready-to-wear and custom-made clothes [Adrian] would design for his own couture house in years to come” (Gutner, 184). A similar suit in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art which dates to c.1950 (fig. 12) is a testament to the lasting power of Adrian’s designs, and shows that he had managed to craft a “signature style” as a fashion designer even before he made a career as one.

Fig. 11 - With her daughter (played by Virginia Weidler) Norma Shearer as Mary Haines. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: AllMovie

Fig. 12 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Women's suit, ca. 1950. Wool. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 56.14.7a-b. Gift of Gilbert Adrian, 1956. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of Art

Fig. 13 - Norma Shearer as Mary Haines. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Author

Mary Haines is allowed a moment of true Adrian glamour in the final scene, when she grows “Jungle Red” claws and finally matches the malice of the other women in an attempt to win back her husband. Photoplay’s Fashion Section describes the costume as “a cloth-of-gold evening coat, which falls from the shoulders, like a great 15th century cloak, and forms a slight train at the back” (Walters, 70). This costume dramatizes Mary’s transformation, as she boldly claims center stage for the first time in the film. In the final shot (fig. 13), the audience gets a close-up look at the luxurious metallic textile and the stylistically structured shoulders for which Adrian was known.

Crystal Allen (played by Joan Crawford)

Adrian is said to have built his career on Joan Crawford’s broad shoulders; and as the malicious shop girl Crystal Allen, Crawford’s shoulders are broader than ever. The actress lobbied relentlessly for the role, despite the fact that Crystal only appears in four scenes of The Women—one in which she wears a nondescript department store uniform and another in which she sits naked in a bubble bath. Dubbed “the cinema’s leading wearer of clothes” by journalist Walter Winchell just two years before, it seemed odd that Crawford would be given so few costumes in what was considered MGM’s greatest fashion film (Gutner, 185). Nevertheless, she managed to make the small role dynamic and memorable, while Adrian delivered the impression of high-fashion glamour in just three looks.

Fig. 14 - Working behind the perfume counter at Black’s Fifth Avenue Crystal Allen (Joan Crawford) makes her first appearance. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Author

Fig. 15 - Joan Crawford getting her hair styled for her performance as Crystal Allen. The Women, 1939. Source: The Best of Everything: A Joan Crawford Encyclopedia

Crystal Allen makes her first appearance wearing her department store uniform, as the nosy Sylvia Fowler brings her friend to the perfume counter at Blacks Fifth Avenue in an attempt to get a glimpse of the “beazel” having an affair with Stephen Haines (fig. 14). They see a sales girl with her back turned—hair fashionably styled—and mistake her for Crystal until she turns around an reveals herself as an older woman. They immediately pinpoint the correct sales girl when the undeniably beautiful Crawford enters. She wears the same hairstyle: short and tightly curled, which called for an intensive permanent prior to filming (fig. 15). Fan magazines took notice, and commented that the short hair trend was “slowly gaining momentum,” and that “the man who started it all, Sydney Guilaroff, M-G-M’s hair stylist, [clinched] it with his hairdresses for ‘The Women’” (Walters, 79). Outfitted in a simple black dress for her first appearance, Crawford must communicate all the allure that the character demands from the neck up. However, even her shop girl uniform bears the distinctive Adrian shoulder pads that she helped to make famous.

In her next appearance, they are even further exaggerated—rendering her a formidable opponent when she encounters Mary Haines at the couture salon following the fashion show. Most imposing about this costume, however, are the dramatic plumes of her hat that extend even beyond the width of her shoulders. The “toque of black velvet that is almost completely hidden by Bird of Paradise feathers” signifies her elevation in social status as her affair with Stephen Haines becomes more serious (Walters, 70). Crawford’s reputation as a romantic lead helps to position Crystal Allen as the object of Stephen’s desire, but the audience is hardly given the opportunity to sexualize her in this film. With the production code regulating the content of every picture produced within the studio system, only partial glances of Crystal’s shapely figure given—whether she be lounging in a bathtub or undressing to try on clothes at the couture salon (fig. 16). She dons a highly ostentatious gold lamé ensemble with matching turban, and looks every bit the movie star the audience expects Crawford to be. It is a fitting costume for her confrontation with Mary Haines, who claims that Crystal is “even more typical than [she] could have imagined,” in her gaudy attire. Mary herself wears an elegant black dinner dress with puffed sheer sleeves and a traditional-looking full skirt. They two women are perfect foils in clothing and character, dramatically juxtaposed within a single frame (fig. 17). The sharp contrast in their costuming heightened the tension in this much-anticipated showdown between MGM’s two reigning queens, whose bitter rivalry was rumored to continue off-screen—perpetuated by fan magazines and gossip columnists (fig. 18).

Fig. 16 - Joan Crawford as Crystal Allen. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: Author

Fig. 17 - Crystal Allen (Joan Crawford) and Mary Haines (Norma Shearer) face off in a couture salon dressing room. The Women, 1939. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Author

Fig. 18 - "THEY DON'T LIKE EACH OTHER...Inside Stories of 31 Hollywood Feuds". Look, March 28, 1939. Source: LOOK Magazine Collection

Joan Crawford’s final costume is the most overtly stylized, and clearly designed to encourage audiences to villainize her character. Consequently, it was the costume in which she was most photographed for the film’s publicity campaign (fig. 19). The gown was described by Photoplay magazine as a “brassiere top and a very full circular skirt are done entirely in gold sequins, and a wide belt is emerald-jeweled and embroidered in gold” (Walters, 79) With its exposed midriff, the dress is the sexiest garment that Crystal wears in the film. Such two-piece evening gowns were fashionable throughout the 1930s, introduced by Madeleine Vionnet in her spring/summer 1932 collection (fig. 20). However, within the context of the film, the skin-baring ensemble comes across as particularly salacious—and every bit as “typical” as Mary and her friends would expect a woman of Crystal’s character would wear. At the same time, the sequins give off a scintillating shimmer that underscores Crystal’s biting words as she exits the film in a blaze of vicious glory—a perfectly tasty cinematic moment crafted by both actress and designer.

Fig. 19 - George Hurrell (American, 1904-1992). Joan Crawford as Crystal Allen in a publicity photograph for MGM's The Women, 1939. Costume design by Adrian. Source: The Best of Everything: A Joan Crawford Encyclopedia

Fig. 20 - Madeleine Vionnet (French, 1876-1975). Evening dress, Summer 1932. Silk, glass. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.52.18.8a, b. Gift of Madame Madeleine Vionnet, 1952. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sylvia Fowler (played by Rosalind Russell)

Surprisingly, Adrian’s most successful designs in The Women are not for the two principal actresses, but for Rosalind Russell as the amusingly mischievous Sylvia Fowler. His playful interpretation of fashionable dress provided a comical coating to Sylvia’s viciousness. Subtle exaggerations of silhouette combined with whimsical accessories lent a delightfully cockeyed touch to the character, making her an instant audience favorite. At first, Russell was thought to be too beautiful for the role; producer Hunt Stromberg wanted “somebody to look funny, to get a laugh every time she pokes her head around a door” (Vieira, 123). Adrian’s designs aided in delivering the desired comedy—like her character, Russell’s marvelous millinery is a-twitter with flighty veils, trembling feathers, and erratic sprays of flowers. A seasoned comedienne, she knew how to manipulate her performance to amplify the eccentricities afforded by Adrian’s costuming, which “caricatured fashions by going to the absurd extremes of newness that were unbecoming and silly looking…but this, too, was a commentary on fashions very much a part of the modern picture” (“Fashion Significances,” 32).

Fig. 21 - "About Color" - Rosalind Russell models her costume from The Women (1939). Photoplay, September 1939. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Media History Digital Library

Fig. 22 - "dressed for the all-seeing eye" Rosalind Russell as Sylvia Fowler. The Women, 1939. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Author

Adrian’s playful approach to designing for Sylvia Fowler is evident in her first costume, modeled by Rosalind Russell in the fashion section of Photoplay (fig. 21), under the heading “About Color.” Though the film was shot in black and white, the author of the article delights in Adrian’s choice to combine various shades of pinks and purples in this eccentric ensemble. When Sylvia removes her cropped jacket with pleated front edging, she reveals a quirky blouse heavily influenced by Surrealism, with three appliqued eyes adorning the chest (fig. 22). In his book, Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years, 1928-1941, author Howard Gutner attests to the designer’s fascination with the trend, and notes the narrative demands of film which usually precluded such Surrealist touches in his previous design work (Gutner, 182). In The Women, Adrian was given the opportunity to experiment with Surrealist elements in both Sylvia’s costumes and in several gowns designed for the Technicolor fashion show. However, when asked about the striking violet eyes on the fuchsia crepe blouse, “Adrian side-stepped significance, and punned he was ‘trying only to keep an eye on fashion’” (Walters, 70). For the fashion show, Adrian has dressed Sylvia in a navy blue and white striped taffeta dress with a voluminous bustle (fig. 23) that bounces amusingly as she scampers about the salon stirring up drama (Gutner, 179). The ensemble is topped with a quirky fontage-like hat with standing grosgrain loops in cyclamen and fuchsia, with an attached net veil that wraps around the neck like a scarf (Gutner, 180). A matching striped knitting bag completes the look, and the constant clicking of her knitting needles add to Sylvia’s frenetic energy.

Fig. 23 - Rosalind Russell as Sylvia Fowler. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: "Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years, 1928–1941" by Howard Gutner

Sylvia’s evening wear, too, bears eccentric design features that tend to correspond with Rosalind Russell’s physicality in each scene. When she visits her “friend” Crystal, she slinks into her palatial bathroom wearing a beige wool crepe dress with a dramatically draped head wrap, and playfully topped with a small “monkey” hat (“Wool Jersey and Crepe in Draped Evening Gowns,” 9). Like her jaunty chapeau, Sylvia gingerly perches at the edge of Crystal’s bathtub (fig. 24). In the final scene, Sylvia wears a strapless gown of black tulle—her shoulders swathed in a matching net shawl, in which she becomes entangled when Mary and her friends lock her in the powder room closet. A tuft of tulle hovers above her head, in a flighty headpiece that also includes a cluster of tiny wing-shaped feathers (fig. 25). Though the costume was designed to play up Rosalind Russell’s comedic performance in the final scene, it was still considered highly fashionable and cited as the source of inspiration for a similar black tulle evening gown available for purchase in Macy’s Cinema Shops following the film’s release (Gutner, 182).

Fig. 24 - Rosalind Russell as Sylvia Fowler and Joan Crawford as Crystal Allen. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Metro. Costume Design by Adrian. Source: Author

Fig. 25 - Rosalind Russell poses for a publicity photograph. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume Design by Adrian. Source: Rosalind Russell: Dazzing Star

Ensemble Costume Analysis

Throughout the picture, the three leading ladies are consistently flanked by supporting actresses wearing dynamic Adrian-designed ensembles that perfectly deliver each character’s personality traits on sight. This is especially evident in the last scene of The Women, in which the entire cast is dressed in their finest gowns for the final showdown in an opulent powder room (fig. 26). One on side, is the alluring Paulette Goddard in a one-shouldered, figure-skimming gown with embellished border trim; and on the other, the sweet Joan Fontaine in a demure white ensemble resembling a glamorized version of a quilted dressing gown. Famed gossip columnist Hedda Hopper makes an appearance as a character very much inspired by herself, wearing a quirky chapeau with curled “antennae”—as if transmitting “dirt” on the feuding women to her eager readers in real time. The viewers see every character side by side, and are presented the full spectrum of Adrian’s designs for the wild assortment of women. Though seen in black and white, the assemblage provides a visual delight of contrasting silhouettes, eye-catching textiles, and varied textures. Amazingly, The Women is still every bit as glamorous now as it was in 1939, which can be credited to Adrian’s deft amalgamation of trends specific to the time period and hallmarks of timeless glamour.

Fig. 26 - Hedda Hopper, Rosalind Russell, Norma Shearer, and Joan Fontaine in the film's final scene. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: "Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years, 1928–1941" by Howard Gutner

Film Analysis: The Opposite Sex (1956)

Overview

W

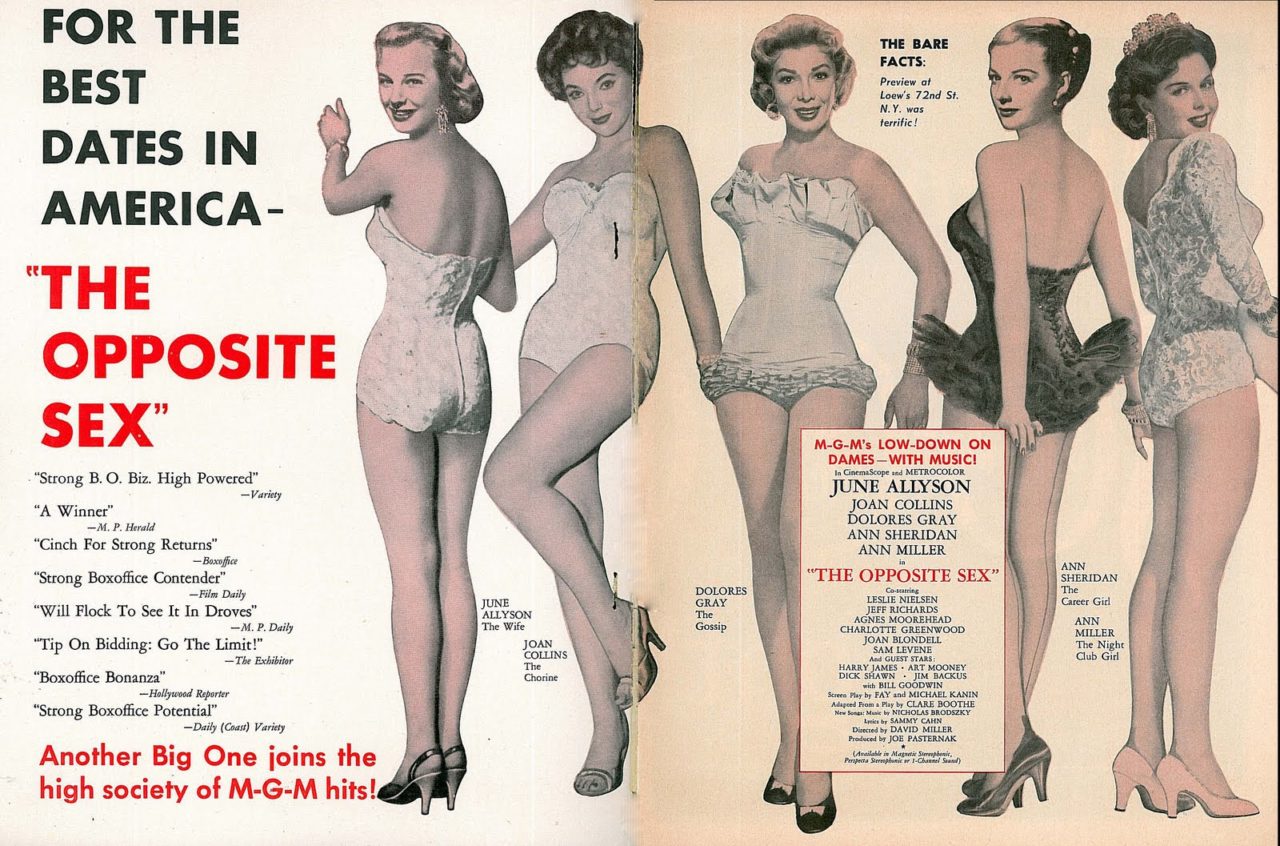

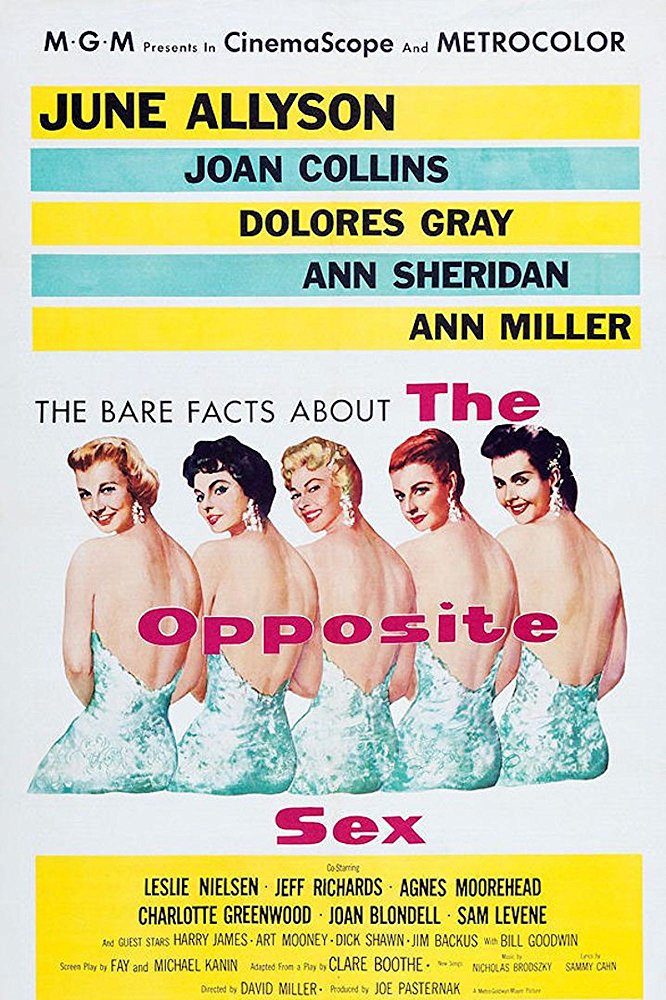

hen MGM decided to do a musical remake of The Women in 1956, producer Joe Pasternak and director David Miller assembled another all-star cast, of comparable caliber to that of the original 1939 film (fig. 27). The remake starred June Allyson, Joan Collins, Dolores Grey, Anne Sheridan, Anne Miller, Joan Blondell, and Agnes Moorehead. Unlike the 1939 film and the original play on which it was based, this version of the story included male characters—and thus, it was retitled The Opposite Sex. Upon its release, many critics “compared the picture unfavorably to the earlier film version, stating that the biting humor of the original had been lost” (American Film Institute). Screen writers Kay and Michael Fanin took the Park Avenue set and relocated them to Broadway, where the idle Manhattan socialites were recast show business wives. However, the remake managed to retain the fashion focus, inspiring reviewers to say, “The Opposite Sex, indeed, is as much a fashion show as it is a musical” (Gertner, 1). As they did in the 1939 film, MGM’s publicity department used fashion to market the picture, sending three models “touring the country…[putting] on fashion shows in leading department stores, with audiences of women rapt with attention” (“Two Perennials,” 13).

Fig. 27 - June Allyson, Joan Collins, Dolores Gray, Anne Sheridan, Anne Miller, and Joan Blondell in an MGM publicity photograph. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Flickr

About the Costume Designer: Helen Rose

Born Helen Bromberg on February 2, 1904 in Chicago, she became fascinated by her mother’s work as a seamstress from an early age (Jorgensen and Scoggins, 256). She got her start designing burlesque costumes as a teenager, and was employed by a small costume house following the stock market crash of 1929. There, she specialized in chiffon ball gowns, and became so adept at working with the fabric that it would become one of her trademarks in her later work as a costume designer. She moved to Los Angeles and began working under (supervising designer) Rita Kaufman at Fox Studios, until her designs caught the eye of Louis B. Mayer. Helen Rose joined the costume department at MGM and became chief designer in 1949, following Irene’s termination (Jorgensen and Scoggins, 260). She would continue Adrian’s legacy at MGM—dressing the industry’s biggest stars, both on screen and off. Rose received much acclaim for the wedding dresses she designed for actresses Elizabeth Taylor, Debbie Reynolds, Jane Powell, and most notably, Grace Kelly, for her wedding to Prince Rainier of Monaco (fig. 28). Like Adrian’s, copies of Helen Rose’s designs were sought after by high-end department stores—especially in the case of the white chiffon dress (fig. 29) that she designed for Elizabeth Taylor in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), which sold by the thousands for $250 each (Jorgensen and Scoggins, 263). She eventually left MGM in 1966 with the twilight of the studio era, and, like Adrian, went on to have a successful career as a private couturiere.

Fig. 28 - Helen Rose. Design for Grace Kelly's wedding dress, 1956. Illustrated by Donna Peterson. Source: "Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers" by Jay Jorgensen and Donald L. Scoggins

Fig. 29 - Elizabeth Taylor as Maggie. Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, 1958. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Costume and Production Design

Fig. 30 - Opening title sequence. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Fig. 31 - The scene of gossip-ridden manicures Sydney’s. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: Author

Fig. 32 - Kay Hilliard's bedroom. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: Author

From the opening title sequence, the audience is immediately placed in the fashionable world of the 1950s, with a close-up vignette that features an unmistakable New Look-inspired bodice (fig. 30). The Opposite Sex had the advantage of having the same art director and set decorator that realized the world of The Women in 1939. They updated Sydney’s to accommodate the aesthetics of the 1950s—with powder pink drapery and swirling marble statuary replacing the original salon’s geometric forms and glass-topped furniture (fig. 31). The Opposite Sex had the aesthetic advantage of being shot in Cinemascope and Metrocolor, “both of which serve to enhance the dazzling gowns the actresses wear and the lavish decor in which they parade them” (Gertner, 1). Art director Cedric Gibbons and costume designer Helen Rose used these technological advances to create cohesive images that achieved harmony through hue, in addition to form (fig. 32). Color would play an important role in Helen Rose’s design approaches to the three leading characters, played by June Allyson, Joan Collins, and Dolores Gray.

Character Costume Analysis

Kay Hilliard (played by June Allyson)

For this remake of The Women, the protagonist’s name was changed from Mary Haines to Kay Hilliard. June Allyson’s character shares the virtuous traits established by Norma Shearer’s performance in 1939. Perhaps a nod to Adrian’s approach to designing for Shearer, Rose introduces Allyson as a dutiful wife by dressing her in a sensible suit (fig. 33). But unlike Mary Haines, Kay Hilliard is given a backstory as a former radio singer—giving Rose permission to design for the character with a bit more flair than would have been appropriate for the character’s earlier incarnations. Still, the overall aesthetic sensibility of Kay’s costumes are relatively muted for a movie musical—consisting of mostly unpatterned, monochromatic textiles. She arrives to her own tenth wedding anniversary party in a soft, beige-pink chiffon gown that almost exactly matches her skin tone (fig. 34). Prevailing ideals of femininity and fashionable dress are evident in this particular costume, which also included touches of rose-colored lace at the bustline and the skirt hem (fig. 35). Helen Rose “was known for her romantic creations, always soft, fluid, and exceedingly feminine ensembles” (Jorgensen and Scoggins, 256). This dress, more than any other in the film, exemplified the design principles for which she was revered.

After obtaining a divorce in Reno, Kay Hilliard returns to her life as a musical performer. But even in the showy MGM dance number, she wears a very non-theatrical costume—a simple blue jumpsuit with a contrast white collar and cuffs, fit for her character’s austere style (fig. 36). Like Norma Shearer, June Allyson is granted a moment of movie star-style glamour in the final scene, where she arrives in a shocking pink gown, ready to claw back at her catty friends (fig. 37). The consistency of this design ideology in both films seems to reaffirm the notion that fashion is inherently associated with women of questionable morality—with both Norma Shearer and June Allyson shedding their virtuous personas (and understated clothing) in moments of wicked glamour. Luckily for fashion-lovers, The Opposite Sex (like the original film) relishes bad behavior—therefore treating audiences to the flamboyant, aspirational designs that they came to the pictures to see.

Fig. 33 - June Allyson as Kay Hilliard. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: Author

Fig. 34 - June Allyson as Kay Hilliard. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: Author

Fig. 35 - Designed by Helen Rose Dress worn by June Allyson. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Sold for $2,500.00 on December 3, 2011. Source: Debbie Reynolds: The Auction, Part II - Catalog

Fig. 36 - Kay Hilliard (June Allyson) performs a musical number. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Fig. 37 - Kay Hilliard (June Allyson) removes her evening wrap in the final sequence. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Fig. 38 - Joan Collins poses on the set. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: IMDb

Fig. 39 - Joan Collins as Crystal Allen. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

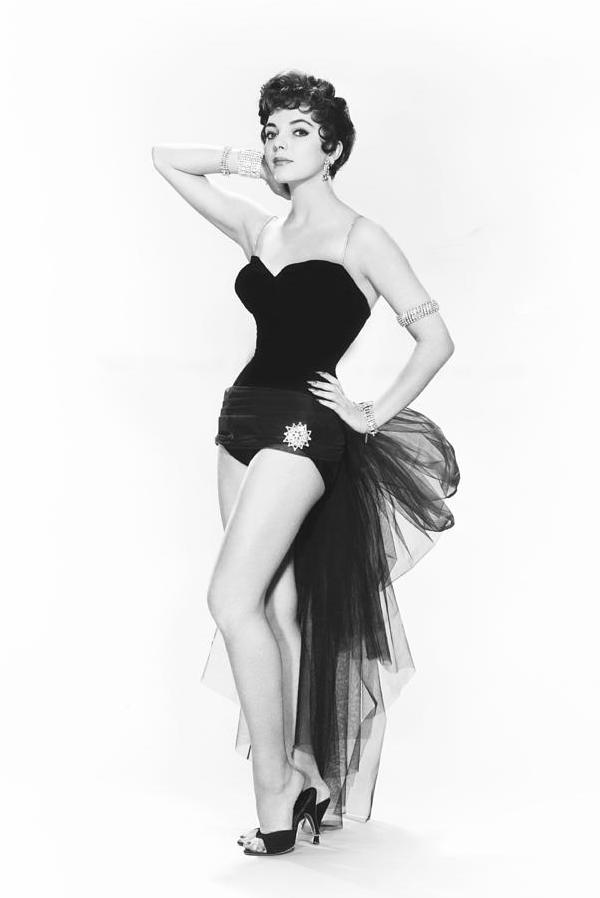

Crystal Allen (played by Joan Collins)

Unlike Joan Crawford in the original film, Joan Collins is overtly sexualized as Crystal Allen in The Opposite Sex. In this later film, the seductive villainess is recast as a conniving chorus girl in producer Steven Hilliard’s Broadway show (fig. 38). Due to her change of profession—or, perhaps a symptom of shifting attitudes regarding feminine beauty and sexuality—each of Crystal Allen’s costumes in The Opposite Sex emphasizes her voluptuous figure and presents her as a physical threat to the comparatively petite Kay Hilliard. During their rancorous dressing room showdown, Crystal strips down to her underwear, as if to assert her sexual dominance over her prudish adversary (fig. 39). Women’s Wear Daily eagerly reported on the one-piece leotard foundation that “[served] as a combination bra, waist cincher, and pantie-girdle” (“Leotard Foundation in New Film,” 4). The same article also mentions a “black velvet leotard of similar appearance over a boned foundation” briefly shown in one of Crystal’s early scenes, as she changes out of her costume after a dance number (fig. 40). Costume designer Helen Rose allegedly received several inquiries from women wishing to purchase the black leotard, despite the fact that it was actually part of a dance costume (fig. 41).

Fig. 40 - Joan Collins as Crystal Allen. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Fig. 41 - Joan Collins as Crystal Allen. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Fine Art America

Throughout the film, Crystal Allen’s clothing quite literally walks the line between fashion and costume, with many of her ensembles transitioning from dance numbers on stage into non-musical scenes. She performs in a musical number for the Hilliards’ charity benefit concert wearing a white strapless gown with a contrasting blue neckline, adorned with a large blue bow with tails that cascade down her back (fig. 42). The otherwise unremarkable dress achieves a degree of theatricality in the daringly high slit in the columnar skirt, which allows Crystal to perform the choreography required by the musical number. Later, off-stage, she seductively slinks over to her dressing room and encounters Kay in the wings, which leads to their much-anticipated confrontation. Even Crystal’s non-theatrical street clothes bear the essence of her affected style. When she meets Steven in the park, she wears a relatively demure white dress with a cardigan draped over her shoulders; however, the sweater is a particularly vampy shade of pink and almost exactly matches the dotted trimming that accentuates her shapely bosom. Of course, the irony is that it is all costume, meticulously designed by Helen Rose to create a stylized reality that actually borders on fashion fantasy.

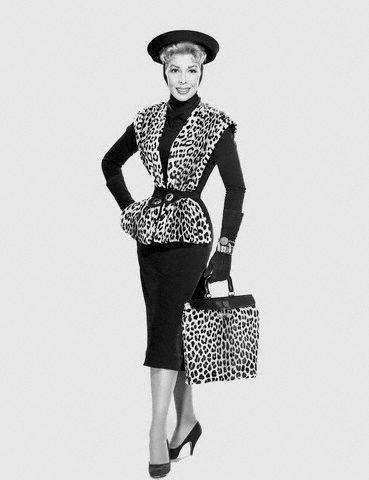

Sylvia Fowler (played by Dolores Gray)

Again, Sylvia Fowler proves to be the true clotheshorse in this film adaptation. Dolores Gray’s interpretation of the sharp-tongued viper is not as humorous as Rosalind Russell’s—due in part to the approach with which Helen Rose designed for the character. Where Russell’s Sylvia used the quirkiness of her costumes to highlight her comedic performance, Gray’s Sylvia is considerably more aloof in her high style. Though Helen Rose uses Adrian’s technique of infusing Sylvia’s costumes with eccentricity through the exaggeration of scale, Gray’s costumes have a degree of seriousness to them in their comparative level of refinement. This may be, in part, due to the disappearance of Surrealism in fashion by the 1950s. However, there is no shortage of novelty in Gray’s wardrobe—even without the quirky “all-seeing eye” blouse. Like the original film, Sylvia boasts the most costume changes in The Opposite Sex and the weight of the film’s fashion appeal rests on her character. Rose has included many homages to Rosalind Russell’s costumes, most noticeably in the draped head coverings that appear in nearly all of Gray’s ensembles (fig. 44).

Fig. 44 - Dolores Gray as Sylvia Fowler. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Fig. 45 - Dolores Gray as Sylvia Fowler. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Fig. 46 - Dolores Gray as Sylvia Fowler. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Getty Images

Although Russell’s costumes were brightly colored in the original film, they only ever appeared on screen in black and white (“Photoplay Fashions: Color,” 51). In the 1956 remake, the full magnitude of Sylvia Fowler’s bold style is brought to life by Technicolor—most notably when she attends Kay’s anniversary wearing a shockingly bright teal taffeta gown with voluminous hip ruffles and a matching cocktail hat (fig. 45). The garish color and ostentatious accessories make this ensemble all the more contrary to Kay’s delicate blush chiffon gown, illustrating the stark contrast between the two characters. Even Sylvia’s comparatively understated daywear bears the hallmark of her flamboyant style. She arrives in Reno wearing a leopard print vest over a sleek, fitted black dress with a high-neck that transitions into another one of her signature head-coverings (fig. 46). She carries a matching leopard-print purse, —reminiscent of Rosalind Russell’s coordinating printed knitting bag—a perfect example of ensemble dressing, which was at the height of its popularity in 1956. This is Helen Rose’s most literal design, appropriately worn during Sylvia’s famous “catfight” scene with her soon-to-be-ex-husband’s new fiancé. Upon her return to New York, Sylvia pays a visit to Crystal Allen wearing a monochromatic cobalt blue ensemble, complete with fitted cocoon coat trimmed with a magnificent dyed fox fur (fig. 47)—as delightfully absurd as the jaunty “monkey” hat worn by her 1939 counterpart. For the final scene, Sylvia arrives wearing an eccentric evening dress of black lace over a nude base with dramatic triple-tiered tulle skirt. The silhouette echoes the effervescent tulle gown sold as part of The Women’s collection at the Macy’s Cinema Shop in 1939. Even the kinetic feathered headpiece that tops Dolores Gray’s coiffed hair quivers in a similar way to Rosalind Russell’s original headpiece. The most unusual feature of this final costume is the half “hood” that extends from the nape of the gown and cups the back of the head (fig. 48). This unique detail perfectly encapsulates Sylvia’s style throughout the film, which vacillates between that of elevated chic and uninhibited absurdity.

Fig. 47 - Dolores Gray as Sylvia Fowler and Joan Collins as Crystal Allen. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Fig. 48 - Detail of Sylvia Fowler's headpiece. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Ensemble Costume Analysis

When the three leading ladies are seen together, as they are in one of the film’s lobby cards (fig. 49), it is evident that Helen Rose used a similar design philosophy to that of Adrian, by making the three distinctive in their styling. Sylvia wears a dramatic, baby pink taffeta evening gown with a voluminous, trumpet-flared skirt—which appears rather gaudy beside Kay’s elegant silver matelassé frock. Both dresses would have been considered quite fashionable to audiences in 1956, and yet create drastically different impressions of the wearers. Helen Rose succeeds in manipulating the reigning fashions of the day to effectively communicate character; however, the structured bodice and nipped waist of the New Look reigns in all three of the designs that appear on the lobby card—as it does for nearly every costume in the film.

Fig. 49 - Lobby card featuring Dolores Gray, June Allyson, and Joan Collins. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: IMDb

This prevailing standard of fashionable dress is most evident in the final scene, especially when compared to the final scene of The Women. When viewed as an ensemble, there is noticeably less variation in design amongst the gowns worn by the 1956 cast; however, similar textiles and consistent silhouettes are effectively transformed by Technicolor, resulting in a confection of varied hues (fig. 50).

Fig. 50 - The ensemble cast in the final scene. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Comparison and Conclusion

When comparing the costumes in The Women with those in The Opposite Sex, one can observe the dramatic evolution of the fashionable silhouette after seventeen years and a world war. Where Adrian’s designs place emphasis squarely on the shoulders, Helen Rose’s designs consistently feature the slimness of the waist—signifying the shift in erogenous zones from 1939 to 1956. The approaches taken by each film’s publicity departments also illustrates the changes seen by the studio system during this time. The advertising for The Women relied heavily on the star power of the three leading actresses—their names commanding the most space (and value) on movie posters in 1939 (fig. 51). The Opposite Sex took an entirely different approach, by posing its stars as playful pin-ups, with their names hardly a quarter of the size of the title’s typeface in a promotional pamphlet distributed prior to the film’s premiere (fig. 52).

Fig. 51 - Lobby card. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Source: IMDb

Fig. 52 - Advertisement featuring the cast in their undergarments. Motion Picture Herald, November 17, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Leaflet by Cato Show Print. Source: IMDb

Fig. 53 - Technicolor fashion show. The Women, 1939. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Adrian. Source: Author

Fig. 54 - Musical number. The Opposite Sex, 1956. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Costume design by Helen Rose. Source: Author

Audiences had also evolved significantly between the two films. Where a ten minute Technicolor fashion show (fig. 53) was enough to create a spectacle in 1939, MGM’s audiences were demanding flashy musical numbers by 1956. Moreover, the presentation of fashion alone was no longer enough to inspire the enthusiasm of movie-goers; The Opposite Sex resorts to a stylized “striptease” to capture the attention of audiences in the film’s “fashion” sequence (fig. 54). Ultimately, what differences in costuming can not attributed to changing ideals or cultural evolution lie in the disparate frameworks that surround the two films. The Women is a commentary on fashionable society, and therefore centers around fashionable dress. The Opposite Sex is set in the world of show business, and therefore is heavily influenced by show costumes. But regardless of whether any adaptation of Clare Boothe’s original work chooses to focus on either fashion or costume, the core of the piece ultimately rests in the absence of men—who disrupt the illusion of the ultimate fashion fantasy for women. This has ultimately become the legacy of The Women, which, despite its poisonous narrative, remains a delicious visual spectacle.

References:

- “Adrian Clothes for The Women Make Definite ‘Type’ Distinctions.” Women’s Wear Daily. September 5, 1939, p. 3, 26.

- “AFI Catalog of Feature Films – The Opposite Sex (1956).” The American Film Institute.<https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/51945>

- “AFI Catalog of Feature Films – The Women (1939).” The American Film Institute.<https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/MovieDetails/5135>

- “Fashion Significances: The Women Packed with Sophisticated 1939 Fashions.” Women’s Wear Daily. September 22, 1939, p. 4, 32.

- Gertner, Richard. Review of The Opposite Sex (1956) in Motion Picture Daily. September 17, 1956, p. 1-3.

- Gutner, Howard. Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years, 1928–1941. New York: Henry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001.

- Jorgensen, Jay and Donald L. Scoggins. Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of HollywoodCostume Designers. Philadelphia: Running Press Book Publishers, 2015.

- “Leotard Foundation in New Film.” Women’s Wear Daily. November 7, 1956, p. 4.

- “Millinery: Variety of Types in The Women.” Women’s Wear Daily. September 1, 1939, p. 1.

- Nugent, Frank S. Movie Review of The Women (1939) in The New York Times. September 22, 1939.

- “Selling Approach: The Opposite Sex—MGM.” Motion Picture Herald. November 17, 1956, p. 37.

- “The Films of Joan Crawford – The Women (1939).” The Best of Everything: A Joan Crawford Encyclopedia. <https://www.joancrawfordbest.com/filmswomen.htm>

- “The Women.” Harper’s Bazaar. September 15, 1939, p. 115.

- “The Women Makes Promotion Headline for Macy’s Fashion.” Women’s Wear Daily. September 22, 1939, p. 32.

- “Two Perennials that Always Sell Tickets.” Motion Picture Herald. October 13, 1956, p.13.

- Vieira, Mark A. Majestic Hollywood: The Greatest Films of 1939. Philadelphia: Running Press Book Publishers, 2013.

- Walters, Gwenn. “Fashion Letter.” Photoplay. September 1939, p. 70, 79.

- ____________. “Photoplay Fashions.” Photoplay. September 1939, p. 49-60.

- “Wool Jersey and Crepe in Draped Evening Gowns Designed by Adrian in The Women.” Women’s Wear Daily. September 5, 1939, p. 9.