Gilbert Adrian’s evening dress is fashionable because it followed the strict guidelines of General Limitation Order L-85 during World War II, but still was able to capture the sense of hopefulness felt by the American people with its playful and uplifting charm.

About the Look

Gilbert Adrian’s playful, floor-length ‘patio’ dress from 1942 is made of silk crepe and features white lambs frolicking in a green flower-filled field on a beautiful day. On the bodice of the dress, you can see birds flying through the blue sky and white clouds overhead. This dress truly represents Adrian’s whimsical genius that helped to shape the way people in America and Hollywood dressed in the 1940s. The dress has the same playfulness and charm that can be seen in his iconic gingham dress for Dorothy (played by Judy Garland) in the film adaptation of The Wizard of Oz (Fig. 1). Although this dress was created during WWII, it symbolized happiness and hope in a time of despair.

Fig. 1 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Dorothy's dress in the Wizard of Oz, 1939. © 1939 Warner Home Video. All rights reserved. Source: IMDb

Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Evening Dress, ca. 1942. Silk crepe. New York: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Janet Gaynor Adrian, 1963. Source: The Met

About the context

Gilbert Adrian, designer to the stars, was probably the most influential Hollywood costume designer to ever live. He was notable for dressing Hollywood icons for several Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films in the mid-1900s, including the likes of Judy Garland, Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, and Greta Garbo. However, he is most renowned for designing Dorothy’s iconic gingham dress for the Wizard of Oz.

In her 1994 FIT thesis “Adrian: The Art & Craft of Motion Picture Costume Design, 1925-1941,” Rebecca Lorberfeld notes that:

“Over time, Adrian came to embody the public’s idea of a costume designer. His was a name synonymous with the high glamour of American films. With Adrian, the art and craft of motion picture costuming achieved full flower.” (xii)

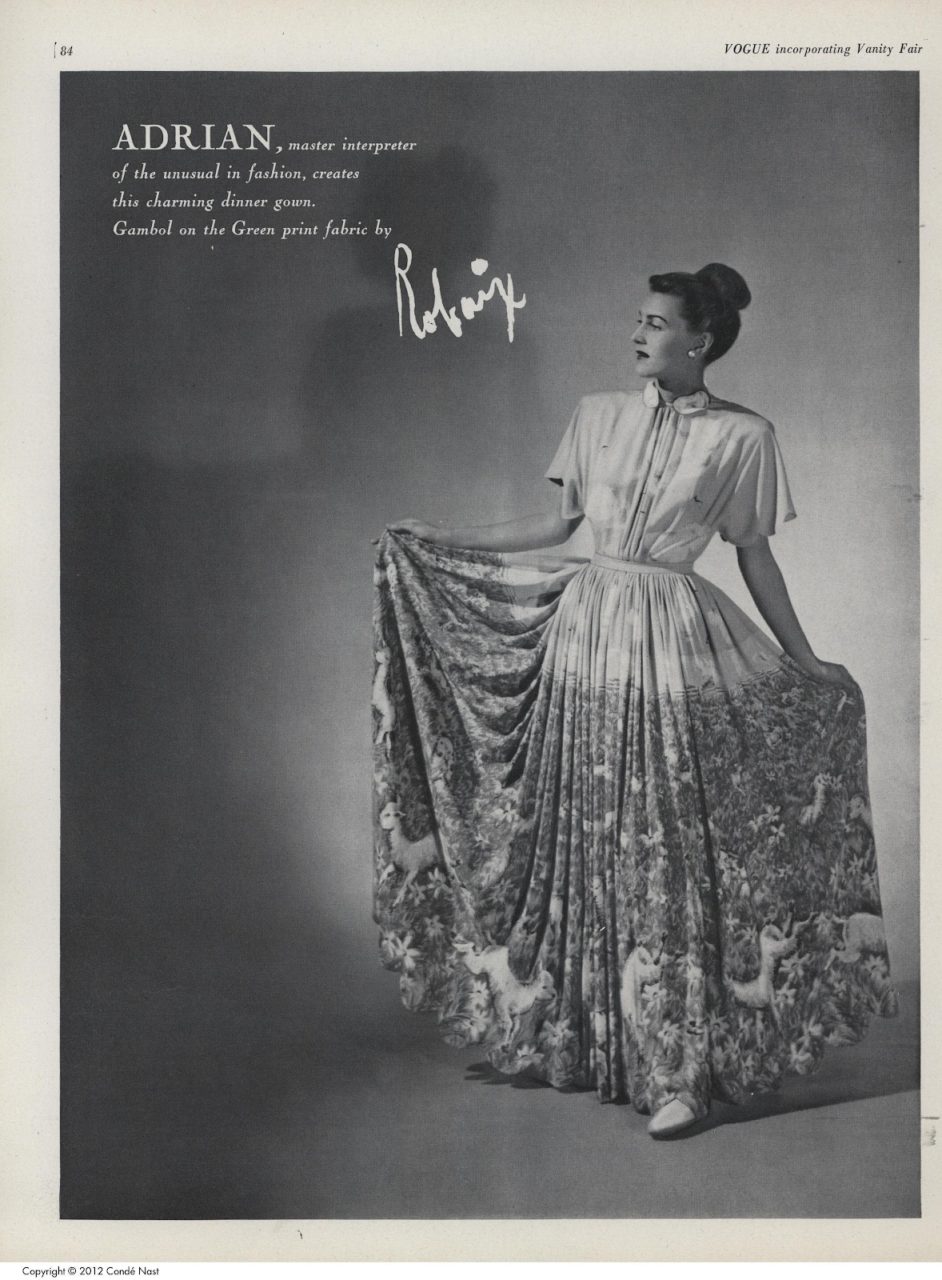

The Vogue advertisement in figure 2 features a model wearing Adrian’s gamboling lamb dress. The Metropolitan Museum of Art which owns the dress described above, previously owned a very similar version (Fig. 3) with a Peter Pan collar and more prominent clouds across the chest, closer to that seen in the Vogue ad.

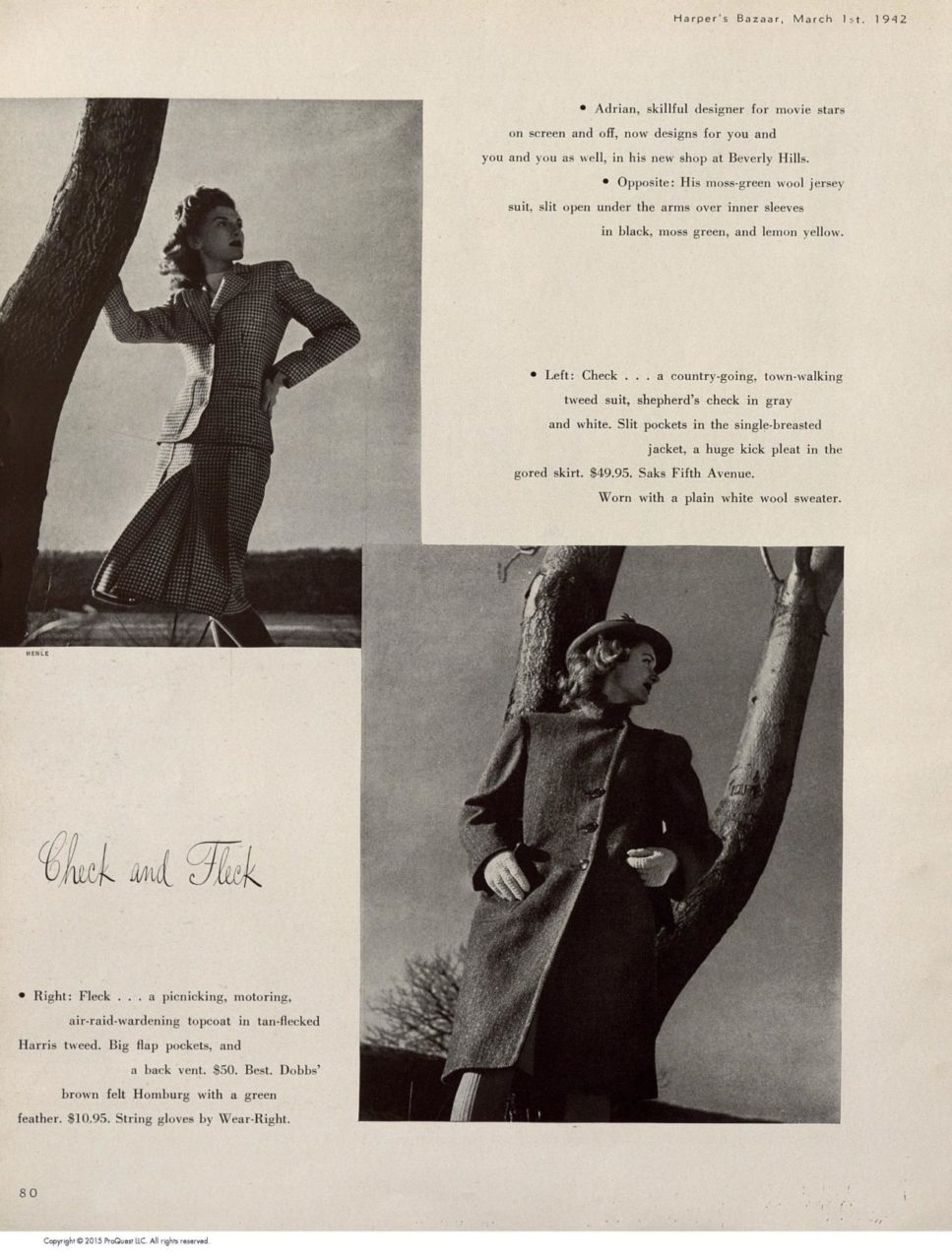

This dress by Adrian is not as opulent as many of his costumes for MGM because it is a more casual dress that could be worn by a 1940s hostess. Adrian’s designs, previously restricted to the Hollywood elite, were finally available to the public with the opening of his Beverly Hills shop. The opening was announced in a Harper’s Bazaar advertisement from March 1, 1942 (Fig. 4) which stated: “Adrian, skillful designer for movie stars on screen and off, now designs for you and you and you as well, in his new shop at Beverly Hills” (80). While the everyday woman could not afford glamorous evening gowns designed by Adrian, his ready-to-wear specialty was suits (Fig. 4) and these fanciful dresses likely also found ready buyers.

Fig. 4 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Adrian opens a new shop in California, 1942. Harper's Bazaar, Vol. 75, Iss. 2762, (Mar 1, 1942): 80-81. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 5 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Ensemble, 1942-1952. Silk, metal. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.538.20a, b. Gift of Patricia Pastor and Barry Friedman, 2012. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850 (2015), Daniel James Cole and Nancy Deihl note that:

“Starting on April 8, 1942, American fashion was shaped by General Limitation Order L-85, which regulated the amount of materials used by clothing manufacturers. Almost as soon as the United States entered the war, the War Production Board asked Stanley Marcus (of Neiman Marcus) to devise a program that would conserve fabric without introducing major stylistic changes, so as not to encourage consumers to discard what they already had.” (202-203)

Since Adrian’s evening dress was created in 1942, it fell under these strict guidelines for rationing during wartime. The acceptable length for evening dresses during this time period was 45″ and the acceptable sweep was 144″. These rules were typically upheld by American designers at the time.

In a Women’s Wear Daily article titled “Vital for Fashion to Fit into Today’s Program” from April 28, 1942, Gilbert Adrian was quoted:

“The most vital thing for fashion to do today is to fit itself into the pattern of the Government. If fashion can’t do this, it has no place. I don’t think that women want to be dreary nor that the Government wishes fashions to be uninspiring or dull. I believe the floor-length dress has a definite place for fall. It is important that women look their best during this trying period–everyone agrees to that–and there is nothing in the restrictions that will prevent them from having flattering gowns for evening.” (3)

These words were definitely on his mind when designing the patio dress. Although this dress was created during a time of fabric rationing, it symbolized a sense of hopefulness in a time of despair with its playful and uplifting charm.

Many of Adrian’s dresses have a whimsical, rustic feel to them. The Adrian ensemble in figure 5 features a charming landscape print with a scene of American soldiers during the Revolutionary War. This was probably a message of patriotism due to World War II. One man, possibly General Washington, is depicted riding a horse.

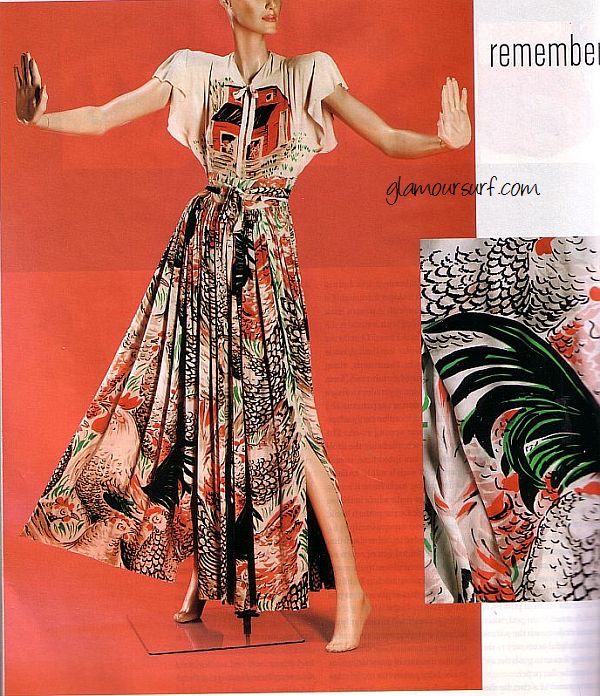

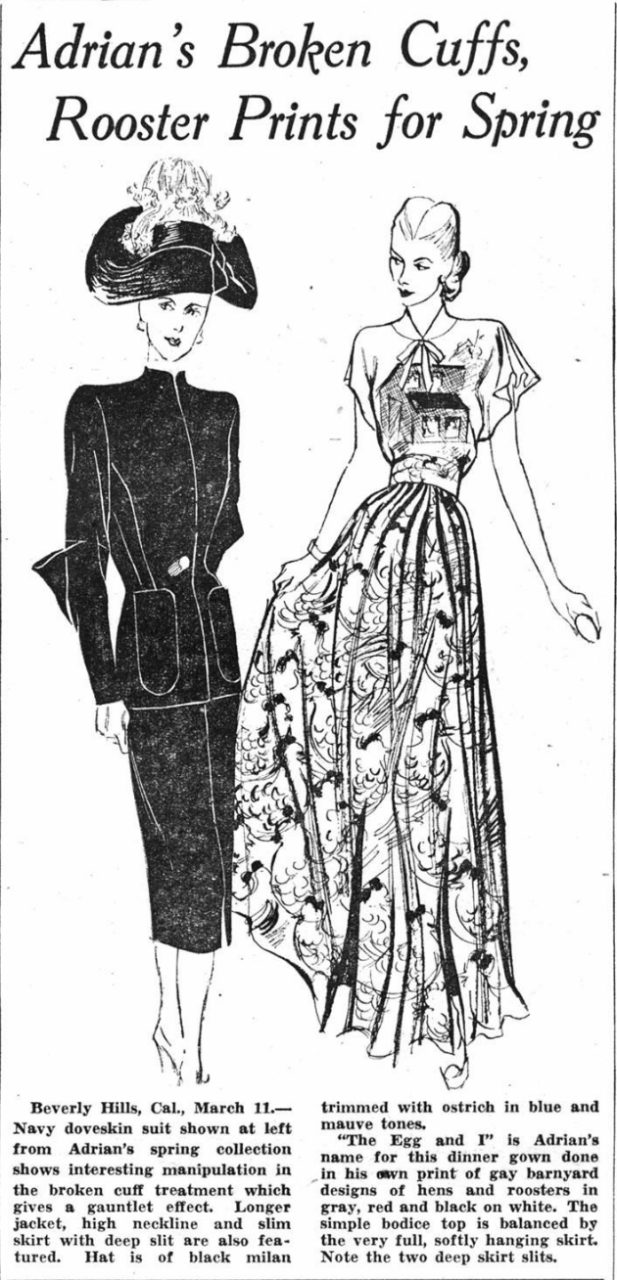

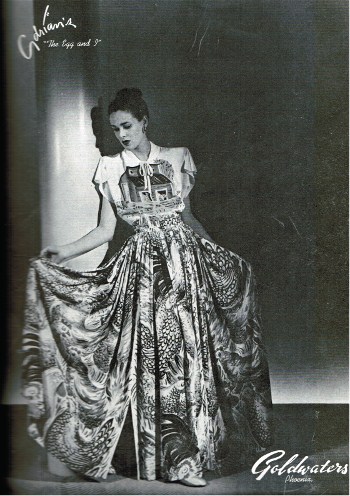

In figure 6, another dinner dress by Adrian, The Egg and I, has striking similarities to the gamboling lambs dress. It features a barnyard scene complete with rooster (Fig. 7). The same dress can also be seen in a Women’s Wear Daily article from 1947 (Fig. 8) and a retail ad (Fig. 9), proving that these gowns were quite popular. WWD describes the gown:

“‘The Egg and I’ is Adrian’s name for this dinner gown done in his own print of gay barnyard designs of hens and roosters in gray, red and black on white. The simple bodice top is balanced by the very full, softly hanging skirt. Note the two deep skirt slits.”

An Abercrombie & Fitch Co. advertisement (Fig. 10) from a Harper’s Bazaar issue dated June 1942 features two similar dresses. However, unlike Adrian’s luxury silk dinner dresses, these midi-length garments were cotton day dresses, suitable for work and home, and were affordable for ordinary women during the time of the General Limitation Order L-85 regulations.

Fig. 10 - Abercrombie & Fitch Co. Cotton Coup!, 1942. Harper's Bazaar, Vol. 75, Iss. 2766, (Jun 1942): 9. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 6 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). The Egg and I, Spring 1947. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 7 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). The Egg and I details, Spring 1947. Source: Irenebrination

Fig. 8 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Adrian's Broken Cuffs, Rooster Prints for Spring, 1947. Women's Wear Daily, Vol. 74, Iss. 50 (Mar 12, 1947): 1. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 9 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Goldwaters advertisement of Adrian's "The Egg and I" dress, 1947. Source: Blue Velvet Vintage

References:

- Cole, Daniel James, and Nancy Deihl. The History of Modern Fashion from 1850. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990642779

- “Evening dress.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/157347

- Lorberfeld, Rebecca. “Adrian: The Art & Craft of Motion Picture Costume Design, 1925-1941.” MA Thesis, Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York, 1994. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1685379467?accountid=27253

- “Vital for Fashion to Fit into Today’s Program, Says Adrian: No Need for ‘Dull’ Clothes, Declares Beverly Hills Designer, Preparing for Fall Collection.”Women’s Wear Daily, Apr 28, 1942, 3. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1627240935?accountid=27253