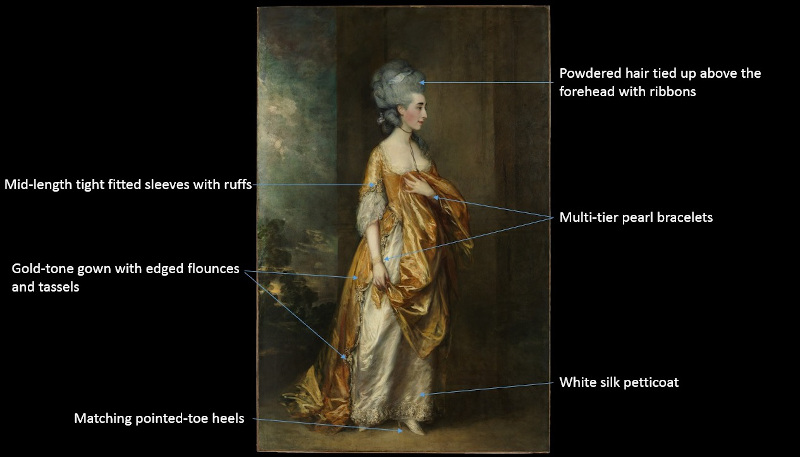

This portrait of Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott (1754?-1823) by English portraitist Thomas Gainsborough was commissioned by Mrs. Elliott’s lover, the Earl of Cholmondeley. First exhibited at Royal Academy, London in 1778, the composition and treatment are reminiscent of Van Dyck.

About the Portrait

T

homas Gainsborough was a famous English painter, draughtsman, and printmaker of 18th century. After short stays in London, Sudbury and Ipswich, Gainsborough moved to Bath in 1759 and achieved popularity there by painting wealthy visitors. His style during this time was influenced by seeing paintings by Anthony van Dyck, the seventeenth-century painter (Rosenthal, Grove). He also remained connected to London: he exhibited at the Society of Arts from 1761 and was a founding member of the Royal Academy in 1768 (Rosenthal, Grove). As Baetjer says, “his eye for female beauty and capacity to capture it on canvas were legendary, as was his instinct for dealing with notable and notorious clients” (39).

This full-length portrait was initially exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1778. The woman depicted is Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott, a Scottish socialite closely connected to the Earl of Cholmondeley, who also commissioned the portrait. The former wife of Dr. (later Sir) Elliott, “Dally the Tall” was known for her beauty and her height, and had liaisons with nobles such as the Earl of Cholmondeley, the Prince of Wales, and the Duke of Orléans (The Frick). She certainly counted amongst Gainsborough’s notable and notorious clients: early Royal Academy catalogs only referred to royals and certain public figures by name, and this portrait was no exception. However, she was famous enough that when the London Morning Post referred to her as “the beautiful Mrs. E.” in the context of this portrait, readers knew her identity (Baetjer 39).

On March 30, 1782, Mrs. Elliott gave birth to a daughter, who was allegedly fathered by the Prince of Wales; this daughter was later adopted by the Earl of Cholmondeley and raised in his family. About one month later, another portrait of Mrs. Elliott by Gainsborough, this time commissioned by the Prince of Wales, was exhibited at the Royal Academy (Fig. 1).

Van Dyck’s influence on Gainsborough is best exemplified through his treatment of drapery and emphasis on the face. The fabric Mrs. Elliott holds to her torso is allowed to fall in folds, highlighting the gleam of the fabric, while Gainsborough’s brushwork grows progressively looser away from her face (Baetjer 39). Similar techniques can be seen in Van Dyck’s 1622 portrait of Teresia Sampsonia, Lady Shirley (Fig. 2). Van Dyck has also highlighted his subject’s face, treating it with a high level of detail. She wears a gold-colored mantel and a matching long-sleeved gown; both appear to be decorated and trimmed with red fabric. Van Dyck’s loose brushwork captures the movement and luxuriousness of the fabric, while hinting at elaborate embellishments.

Van Dyck’s influence was not limited to brushwork, however. He popularized a style of composition where the subject is painted in full, standing before a tranquil landscape, such as in his 1636 portrait of Lady Anne Carey (Fig. 3). Van Dyck’s use of pastoral scenes in his portraits of English aristocrats suggested safety from the volatile politics of the day (The Frick). Gainsborough’s portrait of Mrs. Elliott echoes this composition, though the landscape is seen through an open doorway, and Mrs. Elliott’s surroundings are not immediately clear.

Fig. 1 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788). Grace Dalrymple Elliott, ca. 1782. Oil on canvas; 76.5 x 63.5 cm (30 1/8 x 25 in). New York: The Frick, 1946.1.153. Purchased by the Frick, 1946. Source: The Frick

Fig. 2 - Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Teresia Sampsonia (1579/80-1668), Lady Shirley, 1622. Oil on canvas; 214 x 129 cm (84 1/4 x 50 3/4 in). Petworth: National Trust, Petworth House, 486170. Accepted in lieu of death duties on the estate of Charles Henry Wyndham, 3rd Lord Leconfield, by HM Treasury, 1956; transferred to the National Trust. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 3 - Anthony Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Lady Anne Carey, Later Viscountess Claneboye and Countess of Clanbrassil, 1636. Oil on canvas; 212.1 x 127.6 cm (83 1/2 x 50 1/4 in). New York: The Frick Collection, 1917.1.37. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Source: The Frick

Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727–1788). Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott (1754?-1823), 1778. Oil on canvas; 234.3 x 153.7 cm (92 1/4 x 60 1/2 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 20.155.1. Bequest of William K. Vanderbilt, 1920. Source:

The Met

About the Fashion

The gown that Mrs. Elliott wears emphasizes her figure. Her bodice is low-cut and ends in a point; she wears it over a matching divided skirt and white petticoat. The sleeves of her bodice are tight, ending just above the elbow in loose white cuffs. The edges of her bodice and skirts are lavishly trimmed with lace and pearls. She carries a matching gold wrap, which she uses to cover herself “in a gesture that suggests vulnerability” (Baetjer 39). A similar ensemble can be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum (Fig. 3). The V&A gown shares the overall silhouette and color scheme of Mrs. Elliott’s gown; though untrimmed today, it could have been originally embellished.

Mrs. Elliott has finished her ensemble with fashionable accessories. A white ribbon is threaded through her hair, which is powdered and piled high. Her pointed-toe shoes are embellished on the edges, which echo the details elsewhere on her gown. This style of shoe, called the “Louis” heel, was popular during this time. A similar pair, from the 1780s, are at the Met; they share the same pointed toe and low heel (Fig. 4). For jewelry, she wears small gold earrings, multi-tiered white pearl bracelets around both wrists, and a thin black ribbon around her neck. This black necklace is similar to what she wears in her 1782 portrait, in which a wider ribbon is tied in bowknot.

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown. Woman's Gown, 1770-1780. Silk, linen, silk thread, linen thread. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.104-1972. Given by Miss A. Maishman. Source: The V&A

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (British). Shoes, ca. 1780s. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.63.7.6a,b. Gift of Mrs Frederick Street Hoppin, 1963. Source: The Met

Fig. 5 - Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (French, 1755-1842). Archduchess Marie Antoinette (1755-1793), Queen of France, 1778. Oil on canvas; 273 x 193.4 cm (107 1/2 x 76 1/5 in). Vienne: Kunsthistorisches Museum, 2772. Source: Kunsthistorisches Museum

Fig. 6 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788). Portrait of Anne, Countess of Chesterfield, 1777-78. Oil on canvas; 221 x 156.2 cm (87 x 61 1/2 in). Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 71.PA.8. Gift of J. Paul Getty, 1871. Source: The Getty

Fig. 7 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788). Portrait of Mrs. Lowndes-Stone, 1775. Oil on canvas; 232 x 153 cm (91 1/3 x 60 1/4 in). Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, 429. Acquired by Calouste Gulbenkian from Duveen, in London, on 15th November 1923.. Source: Museu Calouste Gulbenkien

At the same time, Marie Antoinette was setting trends in the French court. Although an Austrian-born princess, she turned to fashion to bolster her prestige in Versailles. Her royal portrait reflects the wearing of vast pannier skirts and whale bone corsets at court, which are implied in Vigée-Lebrun’s 1778 portrait (Fig. 5). In this portrait, Marie Antoinette wears a wide skirt heavily adorned with swags of fabric, trimmed with golden ribbon, and decorated with passementerie. Her bodice and stomacher are covered in lace and ribbons, and she has feathers perched atop her hair.

When compared to Marie Antoinette, Mrs. Elliott can almost appear unfashionable. She does not wear wide, rectangular panniers, her dress is not as highly decorated, and her jewelry is understated. However, this ensemble is acceptable, and even fashionable, as she is an English socialite, and not the Queen of France. The rich fabrics and costly pearls Mrs. Elliott wears indicate that she is certainly wealthy. The two women have a similar hairstyle: both have powdered their hair to a light gray, styled it in poufs atop their heads, and allowed a curled section to drape over their shoulder. Their makeup, too, share similarities; both appear to have rouged their cheeks.

Similar portraits by Gainsborough confirm Mrs. Elliott’s style as fashionable. In a 1777 portrait, the sitter, Anne Thistlewaite, the Countess of Chesterfield, is depicted in an outdoor setting, wearing an ensemble similar to Mrs. Elliott’s (Fig. 6). She wears a light blue low-cut bodice that matches her shimmering skirt, worn over a cream-colored petticoat. Both have eschewed wide panniers, wear pointed-toe shoes, and style their hair in fashionable poufs. A slightly earlier portrait, of Mrs. Lowndes-Stone in 1775, anticipates the overall style of Mrs. Elliott’s gown (Fig. 7). Their ensembles are trimmed at the neckline and at the edges of their skirts, and feature the same tight bodice and sleeves paired with a long, slightly trailing skirt. The composition is close as well, and takes inspiration from Van Dyck; both women stand in similar poses, at a slight angle, in or close to nature.

Its Legacy

Mrs. Elliott’s legendary experience still captures public interest: a contemporary writer, Jo Manning, dug deep into her life for in My Lady Scandalous: The Amazing Life and Outrageous Times of Grace Dalrymple Elliott. Gainsborough’s 1782 portrait of her was used as the book cover (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8 - Simon & Schuster Inc.. Cover of My Lady Scandalous, 2010. Source: Simon & Schuster

References:

- Baetjer, Katharine. “British Portraits: In the Metropolitan Museum of Art”. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 57, no. 1 (1999). The Metropolitan Museum of Art: 1–72. doi:10.2307/3258857.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. London: DK, 2012.

- Frick Collection. “Grace Dalrymple Elliott.” Accessed October 2, 2020. http://collections.frick.org/view/objects/asitem/items$0040:182

- Frick Collection. “Lady Anne Carey, Later Viscountess Claneboyne and Countess of Clanbrassil.” Accessed October 2, 2002. https://collections.frick.org/objects/154/

- Leca, Benedict, Aileen Ribeiro, and Amber Ludwig. Thomas Gainsborough and the Modern Woman. London: GILES, 2010.

- Rosenthal, Michael. “Gainsborough, Thomas.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 10, 2015, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T030414 (subscription required).

- Warren, Geoffrey. Fashion Accessories Since 1500. New York: Drama Book Publishers, 1987.