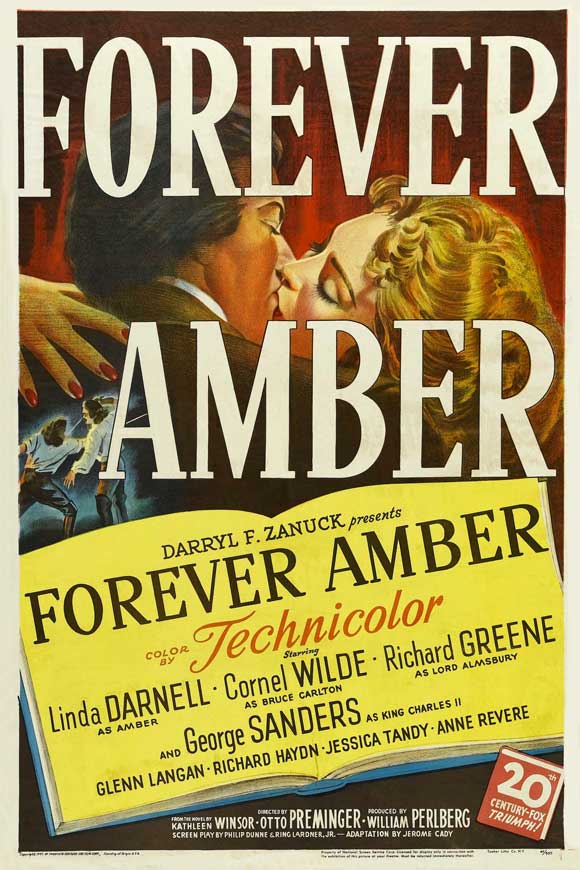

Forever Amber (1947)

Synopsis

During Restoration England, a young and beautiful peasant named Amber St. Claire seduces her way to Buckingham Palace, but loses her first true love along the way.

Directed by

Otto Preminger

Release date

22 October 1947 (US)

Costume Designer

- René Hubert

Studio

- Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation

Source: IMDB

Film trailer

Introduction

Kathleen Winsor published Forever Amber, the 972-page romance novel in October of 1944. By December, Twentieth Century Fox studios purchased the screen rights to produce the film (“Of Local Origin,” 1944). Originally, the film went into production with John M. Stahl directing and Peggy Cummins playing the title character, Amber St. Clair (Nugent, 1946). However, thirty-nine days into filming, rising star Linda Darnell was brought in to replace the relatively unknown Cummings; and Otto Preminger took over for Stahl as director. Production stalling, recasting, and reshooting increased pressure on a massive budget to create a blockbuster. In the end, Forever Amber did not disappoint. Opening weekend broke box office records in the United States. Revenue grossed $5,000,000 that year and it ranked among the most successful films of 1947 (Schatz, 467). The film’s success was perhaps due in part to the levels of protest against its racy and sexual themes, both by the Production Code Administration and the Catholic Legion of Decency (Schatz, 322). One group of Catholic veterans’ protest to prevent the public from watching the film backfired, and instead the theatre was packed with “standing room only” (“New Protest on ‘Forever Amber’,” 1947).

The film also demonstrated the allure of fashion to draw an audience to the theatre through its expensive and extravagant costumes. The men’s and women’s wardrobes totaled $255,000, and Twentieth Century Fox spent $40,000 on wigs (Nugent, 1946). Over $90,000 of the budget went to Amber’s wardrobe alone. For this paper, I will analyze the costumes of Forever Amber designed by René Hubert, focusing on the wardrobe for the female lead, Amber St. Claire.

About the Period Setting

Forever Amber takes place in England between 1660 and 1685, during the reign of Charles II. The reestablishment of the British monarchy coincided with stricter adherence to court fashions (Boucher, 273). Women’s most formal fashion of the period consisted of three outer components (Waugh, 30). First, a bodice stiffened with whalebone, then, an over-gown attached at the waist seam and open in the center front, and finally, a petticoat, left visible and fabricated like a simple skirt. The bodice was generally constructed with an oval neckline which fell over the shoulders and dipped low in the front, with voluminous short sleeves cut wide and gathered low into the armscye, as can be seen in the paintings of Gerard Ter Borch (Fig. 1). The short sleeves of the bodice were intended to display the chemise sleeve underneath, and were edged in lace and tied to the arm with ribbon. The bodice itself was completely rigid and created a flat chest with an exaggeratedly low waistline ending in an extreme point at the center front of the skirt.

Women’s more casual garments emerged in the late seventeenth century. A loose, gown known as the mantua consisted of the bodice and the skirt, pieced together into a loose, flowing gown. The mantua became acceptable for formal wear (Fig.2). A stomacher pinned at either edge of the center front opening of the bodice created a square neckline. Formal or informal dress was worn over linen chemise undergarment. Accessories for women during this period included the fontange, a vertical lace cap, feather and paper fans, and pearl jewelry.

Fig. 1 - Gerard Ter Borch (Dutch, 1617-1681). Woman Reading a Letter, ca. 1660-62. Oil on canvas. London: Royal Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Henri Bonnart (French, 1642-1711). Recueil des modes de la cour de France, 'Dame en habit d'esté', 1685. Print. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.2002.57.16. Purchased with funds provided by The Eli and Edythe L. Broad Foundation, Mr. and Mrs. H. Tony Oppenheimer, Mr. and Mrs. Reed Oppenheimer, Hal Oppenheimer, Alice and Nahum Lainer, Mr. and Mrs. Gerald Oppenheimer, Ricki and Marvin Ring, Mr. and Mrs. David Sydorick, the Costume Council Fund, and member of the Costume Council. Source: lacma.org

Influenced by King Charles II, new standards fashion for men during period took on a less regimented air (Ribeiro, 216). Men’s doublets became shorter, with the linen shirt remaining visible in the front. Men wore breeches; either tightly fitting around the knee or a wide legged “petticoat” style, wide enough to resemble a skirt (Ribeiro, 224). The edges of garments were heavily festooned with brightly colored ribbons, often attaching the breeches and hose. Accessories for the fashionable courtier included gloves, a periwig, high heeled shoes, a coat and a cape. By the middle of the 1660s, fashion had again shifted, and the long vest and jacket began to emerge, setting a precursor the traditional men’s suit (Ribeiro, 230).

About the Costume Design

The introduction of Forever Amber sets the scene of the Restoration period. A child of born during the English Civil War, Amber St. Claire is an orphan adopted by country peasants. When we first see her, she is a surly Puritan teenager being forced to marry a farmer. She wears a simple, tight-fitting black dress with a white apron, a falling collar, and a close-fitting cap–though the cap is insufficient in hiding her long, red hair. Amber later reveals a seventeenth-century fashion plate and a mirror. She spends a moment undressing and readjusting her white cotton chemise to imitate the image she sees. Amber unties the drawstrings at her neck, crosses them around her body, and ties them under her breasts (fig. 3). Though the film directly references the illustration, Amber’s silhouette highlights a key distinction between the 1940s and the seventeenth century: she lacks a corset. Instead, her pushed up and separated breasts show immediately that she is wearing a brassiere under her chemise.

Amber St. Claire makes her first radical transformation from daydreaming peasant to London society lady by chasing down privateer and soldier Bruce Carlton (played by Cornel Wilde). He and his regiment come to stay at the local tavern. It is useful to briefly describe the menswear in the film here, as Bruce and the other men in the film–with the exception of King Charles– wear the same uniform throughout. A long, fitted jacket kept open below the belt, tight breeches tucked in with long over-the-knee boots, and a cape slung over one shoulder (fig. 4). To accessorize, the men wear folded laced collars and technicolor feathered hats. Though the menswear clearly takes inspiration from the fashions of the early 1660s, the film cannot escape its mid-twentieth century appearance: long, uncovered hair, broad shoulders, and tight pants.

Construction elements of Amber’s costume are extremely similar throughout the film. As the film goes on, her ensembles get more and more elaborate, reflecting her social position. Once Amber has ensnared Bruce, he takes her to a dressmaker’s shop, where she is outfitted with a grey wool dress. This dress has full, puffed sleeves with lace visible under the cuffs, and an attempt at the pointed center “V” bodice of the period, though the waistline is much too short, and the shape comes from the tightness at her waist. In this scene, Amber sports a hooded pink shawl with a ruffled edge and matching pink gloves.

Amber changes from this wool ensemble a pale blue striped silk evening gown to join Bruce at the theater (fig. 5). The skirt of the dress is pleated in such a way that both the colors and materials appear monochromatic. However, when Amber moves, the pale blue velvet, silver, and pale pink stripes appear underneath. The dress emphasizes the low décolletage with transparent net fabric around the neckline. Appliqued decoration at the center front of the bodice creates the illusion of a “stomacher.” Extras in this scene wear similar dresses in pastel pinks and greens, with wide, ostrich-plumed hats on both men and women.

Bruce leaves for America, and Amber returns to the dressmaker to repay her debts, wearing a new grey wool dress. This version is more difficult to see, but her headdress (fig. 6) in this scene is reminiscent of the headscarves and à la fontanges hairstyles and caps appropriate to the last quarter of the seventeenth century. When she unable to pay, Amber St. Claire is thrown into debtor’s prison, where she discovers she is pregnant with Bruce Carlton’s child. Amber is rescued by a thief named Captain Morgan, and she converts to a life of crime, changing into a brown and green wool striped ensemble with a dotted veil, green feathers, and heavy makeup.

Captain Morgan is killed in a skirmish, and Amber again needs rescuing. This time a benefactor encourages her to become a stage actress. In the next scene, she is on stage wearing a pale green gown with blue silk capelet, off-the-shoulder sleeves and a center front slit, emulating the ideals of Ancient Greek dress but with a corseted structure. The textile is pleated with a low neckline to emphasize her figure as well as her current occupation. From this ensemble, Amber changes yet again, into a red and white striped dress. Prominently featured here is her black hat with a wide brim and conical-shaped crown trimmed with red berries, perhaps inspired by men’s Puritan hats of the 1660s (fig. 7).

For her last night on stage, Amber is next seen in a more elaborate stage costume consisting of black sequins, a bell-shaped skirt, and long sleeves. A wide circular brimmed hat of nearly invisible tulle supports white feathers which float off of a mass of curls on her head. This show-stopping dress is barely given a moment before Amber again escapes with Bruce Carlton. She is seen next in a gown of pale pink, and blue, and black stripes down the center front and short, puffed sleeves. Her wide, pinched brim hat appears to be inspired by riding habits of the period, but does not match the occasion, or the time period.

Amber and Bruce spend time with their son in the countryside. She wears a yellow linen dress with a folded neckline and transparent sleeves, with a large apron covering the skirt entirely. The loving couple return to London to find the benefactor waiting for them, furious to encounter his rival. The two men duel over her, and Amber comes to witness in a simple hooded cloak and dark dress. When her benefactor is killed and Bruce flees in anger, Amber dons a black mourning dress briefly, wearing her low décolletage, short, full sleeves and embroidery which emphasizes a faux stomacher.

Amber’s next suitor is a Count who requests her hand in marriage, and resourceful Amber agrees to marry the Count. Of course, this provides the opportunity for in an elaborate wedding dress with a gold embroidered bodice and overskirt inspired by the shape of a mantua covering a voluminous tulle skirt (fig. 8). Her usual décolletage is there, of course, with a sweetheart shaped neckline. Lace engageantes flare out at the elbow underneath full sleeves. Amber soon abandons her own wedding to rescue Bruce from the Plague of London; she changes into a traveling cloak with furred edges and lace kerchief on her head.

She nurses Bruce back to health dressed in a blouse with black skirt, apron, and head covering, emphasizing her piety and charity for the man she truly loves. On screen, the blouse appears to be of a soiled linen or cotton. However, the film still (fig. 9) clarifies that the transparent sleeves are decorated with fine metallic beads, merely creating the illusion of dirt. This subtle luxury in Amber’s costume displays the skill in the designer’s will to produce a glamorous depiction of the Restoration period.

Forcing Amber to return to him, the Count shows her off at the court of King Charles. This court scene is the opportunity for René Hubert to display his true costume glamor. Amber wears a staggering silver lamé gown decorated with white tulle, with low, off the shoulder sleeves and twisted fabric wrapped around the bodice (fig. 10). She also wears a large feather pouf, long evening gloves, and a diamond necklace.

The designer takes liberties to enhance fantastical elements, but this dress appears to draw the most inspiration from historical sources. Its layers of metallic, twisted drapery and transparent net highlight the elements of the mantua. It seems possible that the dress was inspired by the painting of Barbara Palmer, King Charles II’s mistress, by John Michael Wright, (fig. 11). The dishabille style portraiture paired with the luxurious materials were intended for allegory and fashionable statements during the seventeenth century. Hubert’s designs for Amber recreate that romantic negligée aesthetic.

Through the events of the evening, Amber wins the favor of the King and also becomes his mistress. The materials of her dresses become more luxurious silks and satins, as in a brown gown topped with more jewels and metallic embroidery that she wears at the court. She also wears a simpler dress in her apartment, with white puffed sleeves gathered with drawstrings, with a black faux “corset” across the waist.

For dinner with the king, Amber dons a gold metallic off the shoulder dress with a folded collar. Prominent lacing in the back gives the illusion of a corset, but is built into the construction of the garment. In the final scene, Amber must say farewell to both her true love and her son. She wears an austere grey satin silk dress with long, tight sleeves and lace cuffs and gauze at the neckline (fig. 12). In both of these final dresses, the tight sleeves are impossibly early for the Restoration period, and appear to much later eighteenth century inspired.

Despite the fact that she was previously known for her dark black hair, Linda Darnell changed her hair color for this role. Her hair is elaborately curled in various wigs by Max Factor, without any emphasis on historical accuracy. Her makeup in the film, by Irene Brooks and Ben Nye, reflects the 1940s fashions of bold lipstick and outlined eyes. An important aspect of Amber’s wardrobe is the jewelry, in pearls and diamonds fabricated by Hollywood jeweler, Eugene Joseff.

Fig. 3 - Unknown. Film Still from Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 4 - Unknown. Promotional still, Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 5 - Unknown. Film still, Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Author

Fig. 6 - Unknown. Film Still, Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Author

Fig. 7 - Unknown. Promotional still, Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - Unknown. Promotional Still, Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Tumblr

Fig. 9 - Unknown. Promotional Still, Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 10 - Unknown. Promotional Still for Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 11 - John Michael Wright (English, 1617-1694). Barbara Palmer (née Villiers), Duchess of Cleveland, ca. 1670. London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 5497. Source: National Portrait Gallery, London

Fig. 12 - Unknown. Film Still, Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Author

About the Costume Designers

Wardrobe director, Charles Le Maire, delegated the costume designs for Forever Amber to René Hubert. A Swiss designer of costumes for stage and films in London before coming to Hollywood, Hubert became a designer at Fox studios in the 1931 (“René Hubert Designing Costumes for Dietrich Film,” 1941). He became known for period dramas, such as That Hamilton Woman (1941), Jane Eyre (1943) and Desiree (1954) (IMDB). Hubert also worked under Jean Patou in the early twentieth century, as well as wholesale millinery (“René Hubert, of London, Designs Wholesale Hats,” 1940). His experience in the fabrication, retailing, and marketing of costume is reflected in his designs for Amber’s wardrobe in the film.

Historical Accuracy

At the time of its release, newspapers commended the film’s commitment to historical accuracy. Reporters acknowledged the research of the author, Kathleen Winsor, as well as the influence of “studio expert” Mme Hilda Grenier, to advise on the etiquette of period films (“Etiquette Arbiter,” 1945). They also hired their own researchers who referenced portraits by court painter Sir Peter Lely, as well as the seventeenth-century diarists Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn (Nugent, 1946). However, there is no mention in major press that Hubert ever referenced historical materials for the costumes.

Despite all of the promotion of historical accuracy, the costumes of Forever Amber reveal more influence from post-war fashions. Nearly every costume for Amber St. Claire consists of the same elements: low décolletage, tightly corseted bodice, puffed sleeves, and a full skirt. A 1947 evening dress by Jacques Fath from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 13) displays nearly exactly these elements with several petticoats removed from the skirt. While technically correct for the seventeenth century, emphasis on the pointed breasts and high, cinched waistline never disappears. Hubert takes cues in proportions, materials, and colors from 1940s fashions, referencing the historicism of the postwar era over the Restoration period itself.

Fig. 13 - Jacques Fath (French, 1912-1954). Evening dress, Spring/Summer 1947. Cellulose acetate. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993.55. Gift of Richard Martin. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Influence on Fashion

Press at the time reveals that the film served more as a fashion promotion than a historically accurate period piece. In Women’s Wear Daily just before the film is given wide release, Charles Le Maire reported that René Hubert’s interpretations of voluminous skirts “add to the list of costume pieces which represent such a trend on stage and screen today” (“Corseted Bodices,” 1947). He was not bashful about admitting the lack of historical focus, but instead clarifies that the costume could “suggest promotions for main floor accessories departments.”

One major concern in the costume budget was the expense of the alterations for Linda Darnell after she replaced Peggy Cummins. In Women’s Wear Daily, Le Maire remarks that Amber St. Claire experiences thirty-eight costume changes in the film, though the edited version only shows twenty-two. When explaining the film’s wardrobe production process in a promotional piece, Le Maire neglects to mention that Amber’s costumes were originally created for Peggy Cummins and altered to fit Darnell. These discrepancies were likely ignored with Le Maire’s intentions to bolster the film’s prestige in costume design.

Extant examples of surviving costumes, as well as sketches and photographs, reveal that a number of these original designs intended for Peggy Cummins were fabricated but not used in the final film. A photograph of René Hubert with a design labeled for Cummins (fig. 14) shows that the producers still made use of these elaborate garments. Although it never appears on camera, Linda Darnell wears the same dress in an advertisement for Forever Amber perfume in Harper’s Bazaar (fig. 15). The Forever Amber perfume was created originally for the best-selling novel and cleverly advertised using René Hubert’s costumes for the film. Forever Amber adopted the fashion marketing strategy of Gone with the Wind (1939), both promoting the fashions from best-selling historical romance novels.

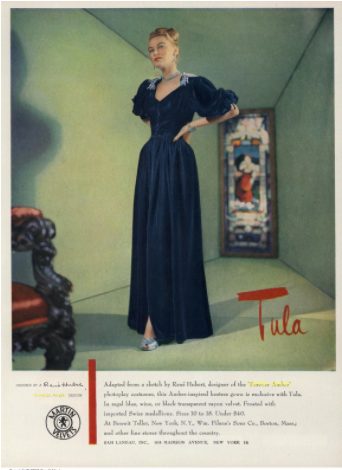

Special fashion screenings were intended to portray the film as an arbiter of contemporary fashion design. In at least one case, marketers took the cue. The magazine BoxOffice noted over 225 windows and counters, from drugstores to department stores, using the promotional materials from magazines and film in Miami Beach (“Amber Campaign Centers on Display in Miami,” 1947). In other instances, Forever Amber inspired versions of contemporary cosmetics and fashion. A sketch of René Hubert’s design for the film was adapted the manufacturer of Tula Velvet fabrics and advertised in Vogue (fig. 16).

Amber’s wide-brimmed hats are depicted in this film with enthusiastic inaccuracy. Entirely out of place for women’s high fashion of the Restoration period, the dramatic headwear fits perfectly into 1940s fashions. For the costume drama Centennial Summer (1946), René Hubert designed the wardrobe, and department stores offered recreations of the millinery worn by Linda Darnell, again the star in the film (“Movie Fashions Spur Retail Promotions,” 1946). The film was a great advertisement and promotion for the millinery departments of the late 1940s, with drama and romanticism emphasizing historicism of the post-war era.

Fig. 14 - Unknown. Promotional Still, Rene Hubert designing costumes for Forever Amber, 1947. Source: Ebay

Fig. 15 - Artist unknown. Forever Amber Perfume Advertisement, Harper's Bazaar, vol. 81, no 2827 (July 1947). Source: Proquest Elibrary

Fig. 16 - Artist unknown. Tula Fabrics Advertisement, Vogue, Vol. 100, No. 9 (November 1947). Source: Proquest ELibrary

Conclusion

The wardrobe department for Forever Amber were not aiming to accurately represent fashion during Restoration England. Though the art directors researched paintings, etiquette and diaries of the period, they lost the overall cohesion of the film. Instead, the costume designers, René Hubert and Charles Le Maire focused on creating a screen spectacle which would entice consumers to see the film for its fashion and purchase similar designs in the shops. Forever Amber presents a case study for the marketing of couture in film for the masses.

René Hubert’s designs for Forever Amber employ the use of corsetry, plunging necklines, and full skirts to create the scene of the 1660s. Elements of these costumes bridge between eras, as they blend between the historicism in 1940s fashion and earlier centuries. The costume designs are successful to represent the story arc of Amber as romantic, scandalous leading lady.

References:

- “Amber Campaign Centers on Display in Miami.” BoxOffice. December 20, 1947.

- Boucher, Francois. 20,000 Years of Fashion. Expanded ed. New York: Abrams, 1987.

- “Corseted Bodices, Off Shoulder Necklines for Forever Amber.” Women’s Wear Daily. October 22, 1947.

- “Etiquette Arbiter.” New York Times. August 6, 1945.

- “Movie Fashions Spur Retail Promotions.” Women’s Wear Daily. July 23, 1946.

- “New Protest on ‘Forever Amber’.” New York Times. November 3, 1947.

- Nugent, Frank. “‘Forever Amber’ Or ‘Crime Doesn’t Pay’.” New York Times. August 4, 1946.

- “Of Local Origin.” New York Times. November 03, 1944.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Fashion and Fiction: Dress in Art and Literature in Stuart England, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

- René Hubert Biography. Internet Movie Database. IMDB.com, Inc. http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0399484/bio?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm. Accessed October 10, 2017.

- “Rene Hubert, of London, Designs Wholesale Hats” Women’s Wear Daily. September 9, 1940.

- Schatz, Thomas. Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s. History of American Cinema, Vol 6. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1997.

- Waugh, Nora. The Cut of Women’s Clothes, 1600-1930. New York: Theater Arts, 1964.