This 1948 dinner dress by Gilbert Adrian is modest and feminine in silhouette but bold and artistic in pattern, taking inspiration from the cubist painter Braque.

About the Look

Fig. 1 - Georges Braque (French, 1882-1963). Still Life with Guitar I (Red Tablecloth), 1936. West Palm Beach, FL: Norton Museum of Art. © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Pari. Source: The Philips Collection

Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Dinner dress, 1948–49. Silk. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.319. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Janet Gaynor Adrian, 1963. Source: MMA.

About the context

Adrian designed this dinner dress (Fig. 2, right) in 1948-1949 for his wife, actress Janet Gaynor, to wear during a trip to Africa that the couple took together. Another dress from that trip can be seen in figure 3; he was clearly inspired by animals outside of America, but perhaps did not realize that tigers are not found in Africa.

Adrian was heavily inspired by the artists of his day, including surrealist painter Salvador Dalí, and cubist painters Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. For his pink, brown, and grey evening dress, he used color blocking and abstract geometry to call out Braque’s paintings in particular (Met). These choices were influenced by Adrian’s personal enjoyment of art and his familial links; his mother had been a painter and his father owned a millinery shop and created caricatures (Gutner 12). One of his earlier collections, made in 1944-45, was inspired by Picasso and used a slightly more neutral palette with curving piecing instead of rectilinear piecing (Fig. 4). These dresses, with their complex piecing and color-blocking, were echoed by other American designers like Elizabeth Hawes (Fig. 5). When Adrian won the Coty award in 1945, these dinner dresses were featured at the awards ceremony to great acclaim.

A Vogue article from the April 1st, 1947 issue describes “The Adrian look for 1947”:

“If a woman were to be dressed by Adrian this year her clothes might be made-to-order or ready-to-wear, since Adrian’s collections include both. The shoulders of her suit would be square-cut, defined, for Adrian continues to cut and shape – but not to exaggerate – these shoulders which are characteristic of him. Her day silhouette could be spare – for Adrian continues the slim silhouette, but uses material freedom when he feels that it gives grace and meaning to a dress…

‘I feel very much the need,’ he says, ‘[of doing] contemporary clothes for a fast-moving century, clothes that are part of the life that women lead today.'” (157)

Adrian made his fame designing for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer movies in the 1930s and successfully branched out to ready-to-wear in the 1940s. His style, especially for evening dresses, retained the cues that had given him so much success with silver-screen starlets: flash and novelty. Wild prints and interesting construction mark his evening wear, and he used both silks and synthetics. But he was also popular for his ready-to-wear suit line, in styles that were usually much more practical and wearable. One of the more decorated Adrian suits can be seen in figure 6 – compare its understated, dark geometric pattern to his vibrant evening gowns.

Adrian paid great attention to construction details. For his ready-to-wear clothing, Adrian made classic styles in better quality than other RTW designers. Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Harold Koda describes:

“The thing that knocks me out is how subtle his details are. You think you’re seeing a nice, good-looking suit, but then you realize its construction is quite complicated. Adrian thought of everything.” (Horyn)

He designed for MGM films, most famously for The Wizard of Oz (1939). His movie-star clients included Joan Crawford, Greta Garbo, and Katharine Hepburn. The deep red beaded gown in figure 7 was made for Crawford for the movie The Bride Wore Red in 1937. Adrian tended to lean towards longer hemlines and fuller skirts, giving an extra pop of glamour and elegance (Dirix 222; Simms 13).

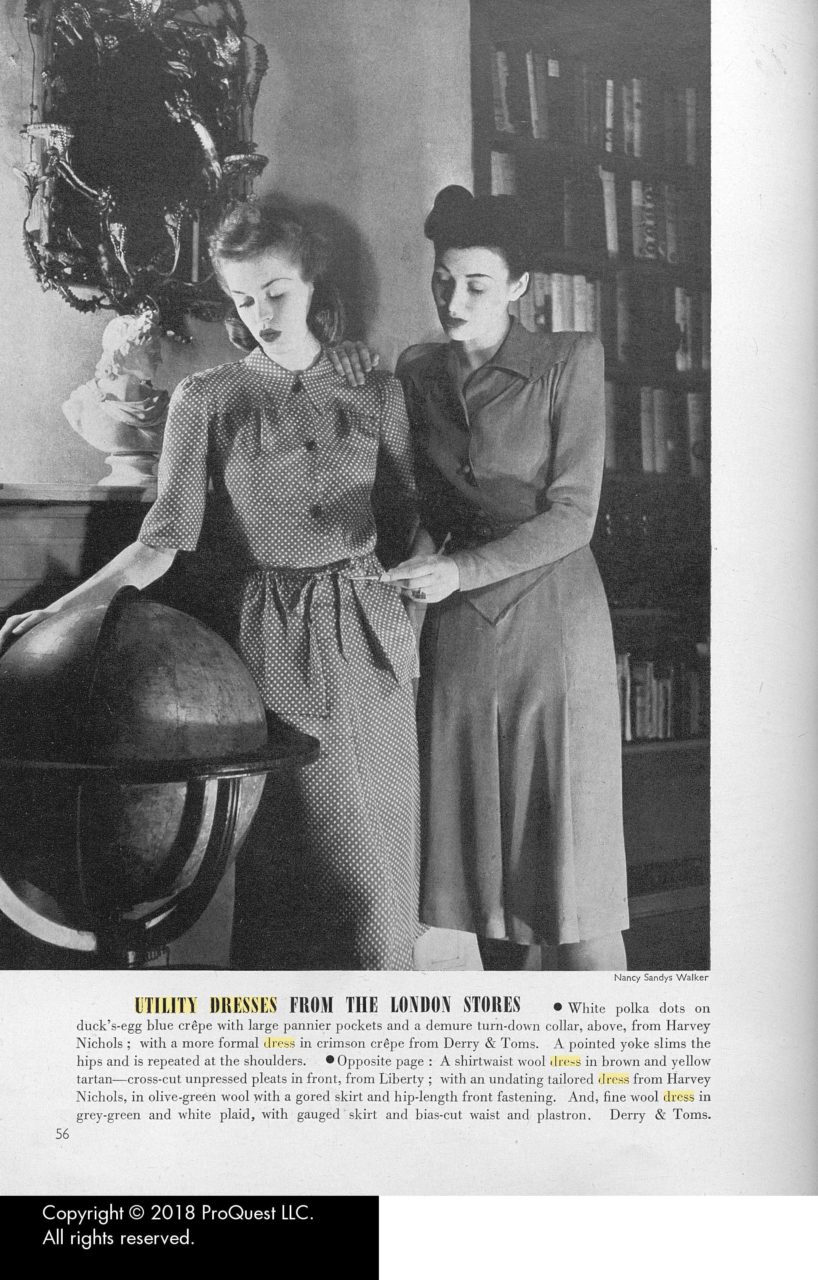

During World War II, ‘utility dresses’ had wide shoulders, calf-length hems, cinched waists, and narrow skirts in an effort to save fabric (Fig. 8). Coming out of the war period, designers began to use more fabric, but continued to use the creative techniques to add flair whilst conserving yardage.

After the war, the most important change in fashion was Christian Dior’s ‘New Look.’ It narrowed the shoulders, cinched the waist, emphasized the hips, and widened the skirt in what many saw as a return to the Victorian era. His designs featured full skirts more than one foot longer than the knee-length skirts that were popular at the time (Walford 8-9 & 84-85; Dirix 210-211). A 1948 Charles James suit in figure 9 showcases these elements with smooth tailoring.

While Adrian flirted with wide hips in some of his dresses, his late 1940s silhouettes were closer in style to those of the late 1930s than they were to Dior’s New Look. This may be a concscious choice as an American; due to the large amount of fabric required for the skirts in the New Look, as well as the necessity of corseting, many Americans criticized Dior’s style. While couturiers did not mind following Dior, this popular feeling meant that RTW designers were less likely to do so. Adrian considered it a trend – meaning that it would go out of fashion too quickly – and felt that it didn’t look flattering to all body types (Pope 31).

In his article “Adrian: American Artist and Designer,” (1974) Joseph Simms says that Adrian should be more highly acclaimed for his work:

“Within his short designing years, he created fashion that is still part of the everyday woman’s wardrobe. But to be more specific, rightfully today, to many, he should be accorded the title of ‘Father of the American silhouette, as contrasted with the Paris silhouette. The broad shouldered look, humorously called the ‘coat hanger’ silhouette with its slim skirt and architecturally detailed jacket, dominated American fashion from 1942-1946.” (Simms 13)

American style was meant to be sportier and more comfortable. Adrian wanted his designs to be timeless, as he told Women’s Wear Daily in 1948: “I have always avoided insisting that an interesting silhouette ever need become a season’s fashion (“Adrian Vetoes” 3). But his prediction did not come true: By the early fifties, the tiny waists and wide skirts of the New Look were widely in demand in the United States (Dirix 1).

Adrian, along with other designers, began using novelty prints and more luxurious fabrics like crepes and organza in the late thirties (Dirix 235). Like in his 1948-49 dinner dress collection, he often used bright colors and artistic prints – but also took it a step further, with barnyard scenes (Fig. 10) and animals like monkeys on his gowns.

Adrian used red, white, and gray stripes on the summer dress in figure 11. This dress, made during the war and before the New Look, has a very similar cut to the pink and gray dinner dress. The yoke is more pointed and the collar slightly lower, but the skirt silhouette and bodice shape are almost identical. This is a good example of how he did now change his style in response to Dior in 1947, but instead made small, slow changes that seemed suitable to him so that women could wear their dresses for a longer period of time.

Fig. 2 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Dinner dress, 1948-49. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.319, 2009.300.320. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Janet Gaynor Adrian, 1963. Source: MMA

Fig. 3 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Evening ensemble, 1949. Silk, metal. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1297a, b. Gift of Janet Gaynor Adrian, 1963. Source: MMA

Fig. 4 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Shades of Picasso, 1944-45. Synthetic. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3913. Gift of The Roebling Society and H. Randolph Lever Fund, 1997. Source: MMA

Fig. 5 - Elizabeth Hawes (American, 1903-1971). Evening dress, 1940. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.2452. Gift of Mrs. George B. Wells, 1957. Source: MMA

Fig. 6 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Suit, ca. 1949. Wool, rayon. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002.326.29a, b. Gift of Jones Apparel Group, USA, 2002. Source: MMA

Fig. 7 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Film costume, 1937. Red bugle bead pavé on silk crepe. New York: Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, 70.8.19. Gift of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Inc.. Source: MFIT

Fig. 8 - Harvey Nichols; Derry & Toms (British). Utility Dresses from the London Stores, April 1944. Crêpe. Harper's Bazaar (Apr 1944), 56. Source: ProQuest

Fig. 9 - Charles James (American, 1906-1978). Suit, 1948. Wool, silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.199a–d. Gift of Arturo and Paul Peralta-Ramos, 1955. Source: MMA

Fig. 10 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Woman's dress, "The Egg and I", 1947. Rayon plain weave, printed; center back length: 142.24 cm (56 in). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.72.59a-b. Gift of Mrs. Thomas Meek. Source: LACMA

Fig. 11 - Gilbert Adrian (American, 1903-1959). Dress, ca. 1944. Cotton. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.335a, b. Gift of Diana S. Field, 1964. Source: MMA

References:

- “Adrian Vetoes ‘Latest Thing’ for Timeless Fashions.” Women’s Wear Daily (Jul 12, 1948), 3. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1862251062?accountid=27253

- “Fashion: The Adrian Look for 1947.” Vogue (Apr 01, 1947), 156-159. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879230308?accountid=27253

- “Dinner Dress.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed October 14, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/158099

- Dirix, Emmanuelle, and Charlotte Fiell. 1940s Fashion: The Definitive Sourcebook. London: Goodman Fiell, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/869917271

- Gutner, Howard. Gowns by Adrian: The MGM Years 1928-1941. New York, NY: H.N. Abrams, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/48967073

- Horyn, Cathy. “Silver Screen Or Mezzanine: His Designs Were for All.” The New York Times, 30 April 2002, Accessed 14 May 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/30/nyregion/silver-screen-or-mezzanine-his-designs-were-for-all.html

- Pope, Virginia. “Adrian’s Designs Exciting, Vibrant: The Collection at Gunther’s Reveals Hollywood Artist Clinging to His Theories.” The New York Times (Mar 02, 1949), 31. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/105744031/158F4FB6569848F4PQ/1?accountid=27253

- Simms, Joseph. “ADRIAN–American Artist and Designer”. Costume 8, no. 1 (1974), 13-17. https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.1179/cos.1974.8.1.13?journalCode=cost

- Walford, Jonathan. Forties Fashion: From Siren Suits to the New Look. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1028458791