This Spring/Summer 1999 ensemble combines angel wings with Arts and Crafts-style woodworking in a statement by McQueen that broke the mold of ’90s minimalism.

About the Look

T

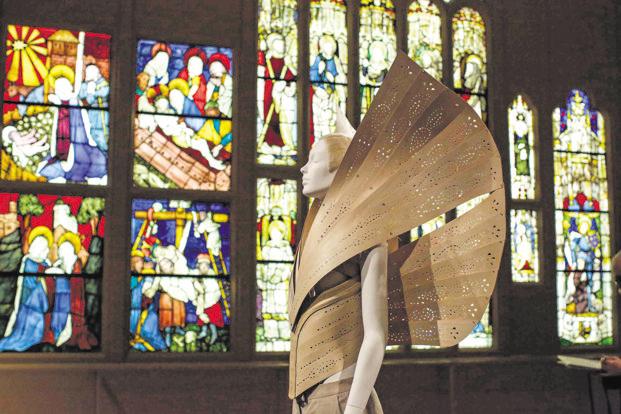

his piece was part of Alexander McQueen’s Spring/Summer 1999 collection, No. 13. It consists of a winged, curving structure made from birch and perforated with a pattern of holes (Fig. 1). It calls to mind the wings of an angel, intermingled with the contrast of carpentry’s hard planes. The full ensemble was styled with low-rise trousers and heels, and features a warm but pale color palette. The simple pair of light tan low-rise, flared pants are a minimal touch and do not pull the viewer’s attention away from the winged bodice. The ‘wings’ are created from thin strips of birch, a very light wood, and the model’s arms slip through the molded structure as it curves to the shoulders. The piece is secured at back with light brown leather straps and gold buckles (Fig. 2). When the ‘wings’ are backlit, the pattern of holes is illuminated, and some light escapes between the strips in a soft look (Fig. 1).

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s description of the ensemble:

“Alexander McQueen’s dazzling creativity and startling originality were expressed through the technical virtuosity of his fashions and the conceptual complexity of his runway presentations, which were suggestive of avant-garde installation and performance art. Rare among designers, he saw beyond clothing’s physical constraints to its ideational and ideological possibilities.”

Fig. 1 - Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Ensemble, Spring/Summer 1999. Birch, leather, metal, wool, silk, lace. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.170a, b. Source: MMA

Fig. 2 - Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Back details of wings, Spring/Summer 1999. Birch, leather, metal, wool, silk, lace. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.170a, b. Source: MMA

Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Ensemble, Spring/Summer 1999. Birch, leather, metal, wool, silk, and lace. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art , 2011.170a, b. Purchase Gift of Roberto Cavalli. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

About the context

There were multiple inspirations for this piece. In Alexander McQueen: Evolution (2012), author Katherine Gleason explains:

“Alexander McQueen’s inspiration for this show – his thirteenth – lies in a variety of sources, including Arts and Crafts, the design movement that was popular between 1860 and 1910, Arts and Crafts practitioners, such as William Morris, reacted against the use of machines by emphasizing handcrafting and natural forms.” (59)

Indeed, McQueen was channeling Morris’ guiding principles when he worked a plain and yet artistic piece of wood into his haute couture, as it brings to mind traditional craftsmanship. The Arts and Crafts design movement in the late 19th century rejected modern industry and focused on handcrafted work and technical skill – something that inspired McQueen himself. In the close-up in figure 3, the fine detail and careful curves in the strips of balsa wood are visible as it caves into a v-shape along the upper body. Yet thanks to the careful choice in material, it seems light as a feather as it flutters along the catwalk carried by the model. The dramatic shapes and size of the wings is even more pronounced in a side profile (Fig. 4).

No. 13 opened with model Aimee Mullins in a pair of hand-carved prosthetic legs and a stitched-together leather bodice (Fig. 5). The Art Nouveau artistry of the legs can be seen in figure 6. But while it opened with an ensemble devoted to leather- and wood-work, No. 13 closed with pure technology: model Shalom Harlow revolved on a turntable as her white dress was sprayed by two industrial paint sprayers (Fig. 6). By the end of it, her dress dripped acid green and harsh black as she continued down the catwalk. No. 13 was a unique McQueen statement on history, artistry, and technology.

Fig. 3 - Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Alexander McQueen - Spring/Summer 1999, Spring/Summer 1999. Birch, leather, metal, wool, silk, lace. Model: Erin O'Connor. Source: Flickr

Fig. 4 - Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Close up side profile of wings, Spring/Summer 1999. Birch, leather, metal, wool, silk, lace. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Source: VAM

Fig. 5 - Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Ensemble, Spring/Summer 1999. Corset of brown leather; skirt of cream silk lace; prosthetic legs of carved elm wood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Savage Beauty

Fig. 6 - Bob Watts and Paul Ferguson (for Alexander McQueen) (British, active 1978-present). Prosthetic Legs, Spring/summer 1999. Carved ash wood. London: Victoria & Albert Museum. Source: VAM

Fig. 7 - Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Look 75, Spring/Summer 1999. Model: Shalom Harlow. Source: Vogue

While many in the audience enjoyed the spectacle, not everyone reacted well to McQueen’s provocativeness. In her 1999 article “Vogue’s View: The Extreme Team,” writer Katherine Betts described how some “critics were quick to denounce what they considered McQueen’s exploitation of a handicapped model” (216). In the Met’s blog on their Savage Beauty exhibition, they feature an interview with Mullins, who describes how difficult and restricting the ensemble was to wear and walk in to the point that she was chanting to herself, “Okay, you’ve done the Olympics…You can survive [this].” (“Ensemble, No. 13, spring/summer 1997,” Met)

The 1990s was a period of extremes, contradictions, and an influx of new ideas. Trends, especially subcultures, were taking over the scene and McQueen’s collections defied the period’s minimalism. His collection was unusual for the time, but he specialized in being dramatic and provocative. As he said in 2009: “Fashion should be a form of escapism and not a form of imprisonment” (WWD Staff, 7). He railed against the minimalistic monotony of the late ’90s, challenging the status quo and providing something that many understood as raw and authentic.

No. 13 included multiple wooden garments or accessories. Another use of wood was seen in a huge fan skirt on the 55th ensemble, which had similar perforated patterns to the winged bodice in figure 1 and allowed a pattern of light and shadows to appear on the model’s legs (Fig. 8). McQueen’s use of wood later influenced other designers like Rodarte (Fig. 9).

In her 2012 article “Wooden Fashion,” Alessandro Masetti claims:

“As a precursor of fashion trends, [McQueen] has inevitably influenced the Spring Summer 2011 collection of the visionary Mulleavy sisters of Rodarte and the Fall/Winter 2011 by the provocative conceptual designer Phoebe Philo, creative director of the brand Céline. Both the brands have used similar wood planks prints, according to their own stylistic codes: ruffles and layers for Rodarte, minimal lines and squared shapes for Céline. Same basic idea, but very different interpretation.”

The sculptural, winged bodice was chosen to appear in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heavenly Bodies exhibit in 2018 (Fig. 10). Curator Andrew Bolton in Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination (2018) connects the wings to angelic figures, and the hard edges and encasement of the body to a sense of the robotic:

“A more industrial but no less poetic depiction of God’s celestial messenger appears in an ensemble by Alexander McQueen that explores the tensions between man and machine.

McQueen’s angel, made from machine-cut, hand-punched strips of plywood shaped and finished by hand, pairs with a hand-carved oak altar frontal in which two registers of angels observe the Coronation of the Virgin and the Adoration of the Magi.” (300)

Compare this piece to an earlier McQueen angel, from his Givenchy Haute Couture Spring/Summer 1997 collection (Fig. 11). The wings in the older piece are a pure white, resemble feathers, and are smaller in scale than his ensemble in his No. 13 collection – overall, the bodice is not only more traditional but also more wearable. The Givenchy bodice exudes elegance and softness rather than an air of creative carpentry.

The winged birch-wood bodice from No. 13 drew on historical inspirations to fight the minimalism and modernism of the late 1990s, but in itself was a minimal, modern use of traditional iconography and craftsmanship. No. 13 is said to be the only show to have brought McQueen himself to tears, and he described his motivation for the project as “to show that beauty comes from within.” (22)

Fig. 8 - Sølve Sundsbø (Swedish, 1970-present). McQueen balsa wood fan skirt, 2011. Photograph. Source: Almighty Publishing Group

Fig. 9 - Rodarte (Kate and Laura Mulleavy) (American, Active 2005-present). Look 25, Spring 2011 RTW. Model: Patricia van der Vliet. Source: Vogue

Fig. 10 - Alexander McQueen (British, 1969-2010). Ensemble in Heavenly Bodies exhibition, Spring/Summer 1999. Birch, leather, metal, wool, silk, lace. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.170a, b. Source: Accessories Magazine

Fig. 11 - Alexander McQueen for Givenchy (British, 1969-2010). Givenchy's Haute Couture Spring/Summer 1997 show, Spring/Summer 1997. © Daniel Simon. Source: Vogue

References:

- Betts, Katherine. “Vogue’s View: The Extreme Team.” Vogue, Mar 01, 1999, 212-225. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/904356585?accountid=27253

- Bolton, Andrew, Barbara Drake Boehm and Katerina Jebb. Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1040993433

- Bolton, Andrew, Harold Koda, Tim Blanks, and Susannah Frankel. Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/851982258

- “Ensemble, No. 13, spring/summer 1997.” Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 5 June 2020. https://blog.metmuseum.org/alexandermcqueen/ensemble-no-13/

- “Ensemble | spring/summer 1999.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed March 6, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/163152

- Gleason, Katherine, and Simon Collins. Alexander McQueen: Evolution. New York, N.Y: Race Point, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/823779702

- “Wooden Fashion.” The Fashion Commentator, November 29, 2012. Accessed 29 April 2020 https://www.thefashioncommentator.com/2012/11/wooden-fashion.html

- WWD Staff. “Alexander McQueen: A True Master.” Women’s Wear Daily, Feb 12, 2010, 1-8. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1434356233?accountid=27253