Charles James’ 1955 “Butterfly” gown features a body-conscious sculpted sheath and large bustle skirt, which is reminiscent of the tightly fitted bustle dresses of the early 1880s.

About the Look

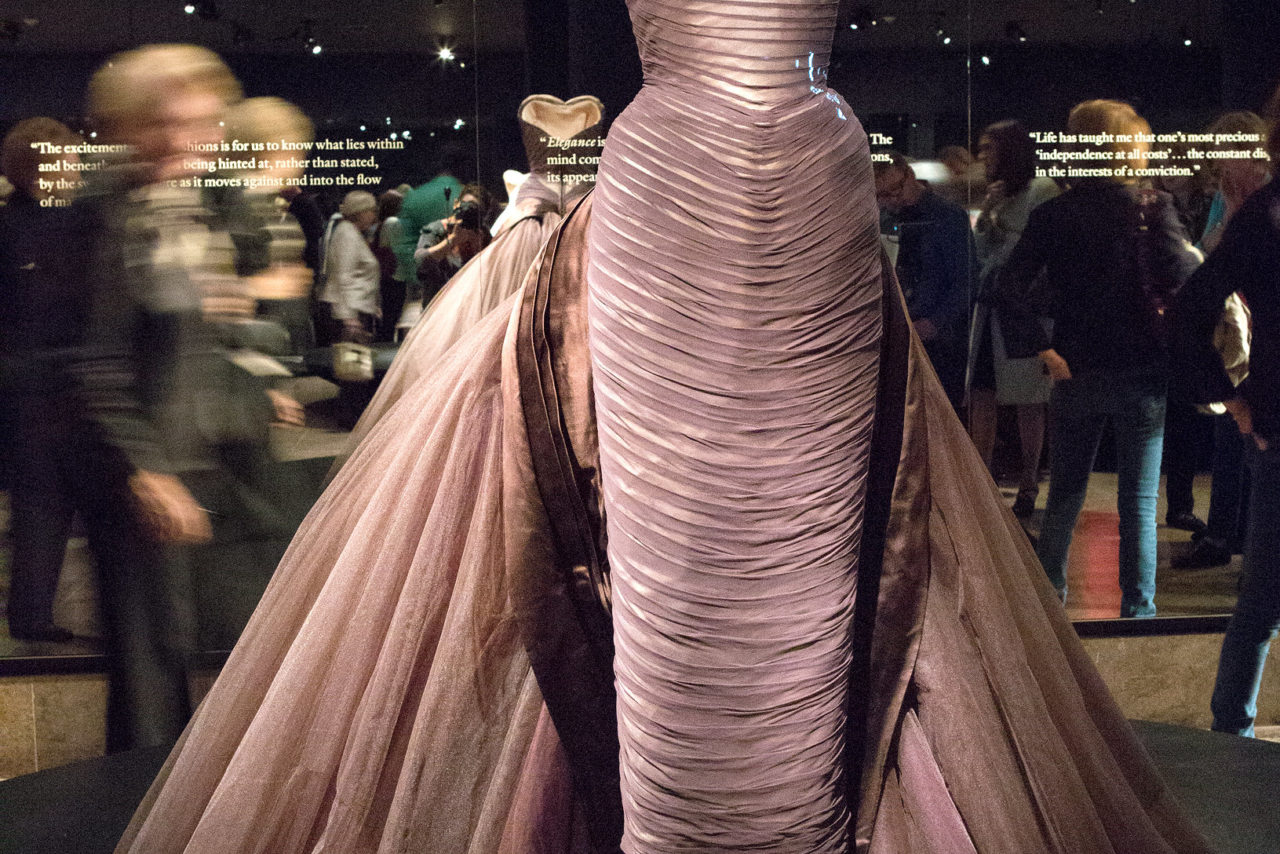

Charles James’ “Butterfly” dress is perhaps one of his most notable garments since it embodies his exquisite attention to detail and architectural capabilities (Figs. 1-2). In order to display his expertise in the relationship between form, color, and texture, James often utilized similar fabrics in different colors, or different fabrics in similar colors. By taking advantage of the different textural qualities of varying fabrics and colors, James was able to create extraordinary dimension in his garments. “Butterfly” features a cream and brown color palette however, its neutral shades do not compromise the luxurious drama the dress exudes (“Butterfly,” Metropolitan Museum of Art). James also included unexpected pops of color by including purple tulle in the billowing skirt fabric which could be revealed when the dress was in movement (Fig. 3).

Made from silk chiffon, silk satin, and twenty-five yards of nylon tulle, the dress wrapped the wearer’s body in sensual femininity and extravagance. Weighing a total of eighteen pounds, the enormous bustle skirt moved swiftly with the wearer’s body and its satin side flanges emulate the beauty of a butterfly’s wings. In fact, this dress was so extravagant that an owner of the gown claimed to have bought two opera seat tickets, one for her skirt and the other for the burst of tulle, or “wings,” of her butterfly dress (Coleman). Additionally, James often implemented quite complex and innovative construction techniques in order to achieve his desired silhouette.

To create detail on the body-conscious sheath of the “Butterfly” James used a labor-intensive tucking treatment also featured in his “Swan” gown. A wide satin band was utilized to control the volume and drama of the tulle bustle skirt, as well as seamlessly disguising the structural components of the dress. His use of architectural treatment, labor-intensive design techniques, and training as a milliner all contributed to James’ spirit of experimentation and zest for unconventional design approaches, including that seen in the “Butterfly” (Koda).

The “Butterfly” gown’s body-conscious sculpted sheath and large bustle skirt is reminiscent of the late Victorian tightly fitted bustle dresses of the early 1880s like those seen on James Tissot’s Provincial Women (Fig. 4). James often utilized similar voluminous shapes and construction methods, especially drapery, to achieve an elegant design that highlighted the feminine form of the wearer. Cinching the waist and featuring an explosion of tulle “wings” this garment transforms the wearer into a beautiful butterfly, which is similar to Dior’s infatuation with depicting women as flowers. James’ use of silk chiffon, silk satin, and nylon tulle textiles in variations of cream and brown reflected the technological advancements and popularity of experimenting with different fabrics at the time.

Fig. 1 - Charles James (American, 1906–1978). "Butterfly", 1955. Silk, synthetic. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.816. Gift of Mrs. John de Menil, 1957. Source: The Met

Fig. 2 - Charles James (American, 1906–1978). "Butterfly", 1955. Silk, synthetic. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.816. Gift of Mrs. John de Menil, 1957. Source: The Met

Fig. 3 - Charles James (American, 1906–1978). "Butterfly", 1955. Silk, synthetic. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.816. Gift of Mrs. John de Menil, 1957. Source: The Met

Fig. 4 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Provincial Women, ca. 1883-85. Oil on canvas; 147.3 x 102.2 cm (57.9 x 40.2 in). Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Charles James (American, born Great Britain, 1906–1978). “Butterfly,“ 1955. Silk, synthetic. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.816. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. John de Menil, 1957. Source: The Met

About the designer

B

orn in 1906 in Surrey, England, Charles James (Fig. 5) had a privileged upbringing, living between Chicago and Britain. Despite having no formal training in fashion, he began his design career as a milliner in Chicago at the age of nineteen with his shop “Boucheron.” Through on-the-job training, James adopted an unconventional design aesthetic. James’ close connection with the photographer Cecil Beaton (Fig. 6) allowed him to set up a dressmaking business at 15 Bruton Street in London. In 1945, James opened his own workroom and salon at 699 Madison Avenue in New York City, where the “Butterfly,” was manufactured (Koda). Treating his garments as individual works of art by sculpting fabric into miraculous gowns, James acquired a star-studded roster of clientele which included the likes of Millicent Rogers, Austine Hearst, and Gypsy Rose Lee. His skills as a sculptor, architect, engineer, and creative drove his complex design approaches and ability to transform the natural body into something unnaturally exquisite. Described as an “architect in cloth,” James designed with artistry in mind rather than commercial selling (Reeder).

Considering James approached his work in a rather art-focused, unconventional manner, his designs can be described as elegant and timeless—while others had odd, insect-like features. While some pieces embodied modernity, others drew on the features of opulent Victorian fashions including the corset, bustle, and crinoline. His garments transformed a woman’s anatomy into a structure that changed her natural shape, and this approach is found within the “Butterfly.” James utilized complex seaming and several techniques such as spirals and wraps, drapes and folds, and anatomical cut in order to sculpt the dress for the wearer. The “Butterfly” embodies Romantic ideals as well the idealization of the wearer’s natural form with exterior drapery and innovative construction techniques. Additionally, “Butterfly”, features a combination of fabrics with different textures, colors, and seam work that hugged the body, giving life to the original, artistic essence of Charles James evening-wear (Reeder).

Fig. 5 - Michael A. Vaccaro (American, born 1922). Fashion designer Charles James in his workshop, May 16, 1952. Photographic print. Washington, DC: Library of Congress. LOOK Magazine Photograph Collection. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 6 - Cecil Beaton (British, 1904–1980). Charles James Ball Gowns, 1948. New York: Condé Nast Archive. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art

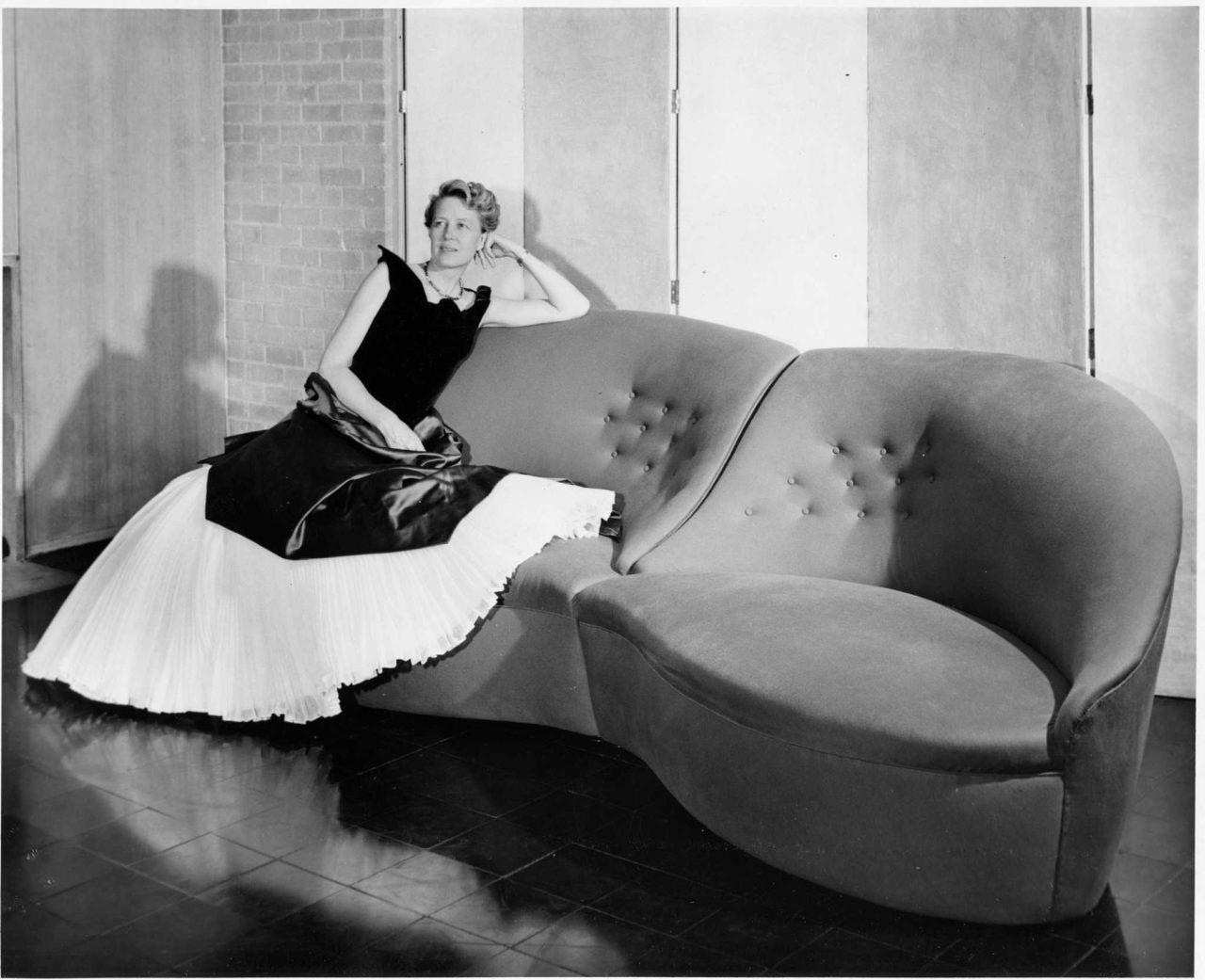

Charles James’ structural qualities and architectural capabilities are evident in the “Butterfly” with the tucking treatment applied to the bodice as well as its ribcage-like structure. James approached the design and construction of this dress with an artistic mindset, enabling him to create a structured, anatomical garment that captured the essence of femininity and grandeur. Considering James was no stranger to the world of art and architecture, it is no surprise that his eye for interior design led to the creation of the “Butterfly Sofa” in 1952 (Fig. 7). This piece of furniture was roughly inspired by the shape of the lips in Man Ray’s 1936 painting The Lovers (Fig. 8). James’ Romantic influence and awareness of the arts allowed him to create a beautifully structured and highly feminine gown like the “Butterfly” (Middleton, “There is a fantasy that propels his mind forward,” System, 2013).

Fig. 7 - F. Wilbur Seiders. Dominique de Menil in a Charles James gown seated on a sofa of his design, 1951. Houston: The Menil Collection. Courtesy of Charles B. H. James and Louise D. B. James. Source: ELLE Decor

Fig. 8 - May Ray (American, 1890–1976). Observatory Time: The Lovers, 1932–34. Oil on canvas; 100 x 250.4 cm. Private collection. Source: WikiArt

About the wearer

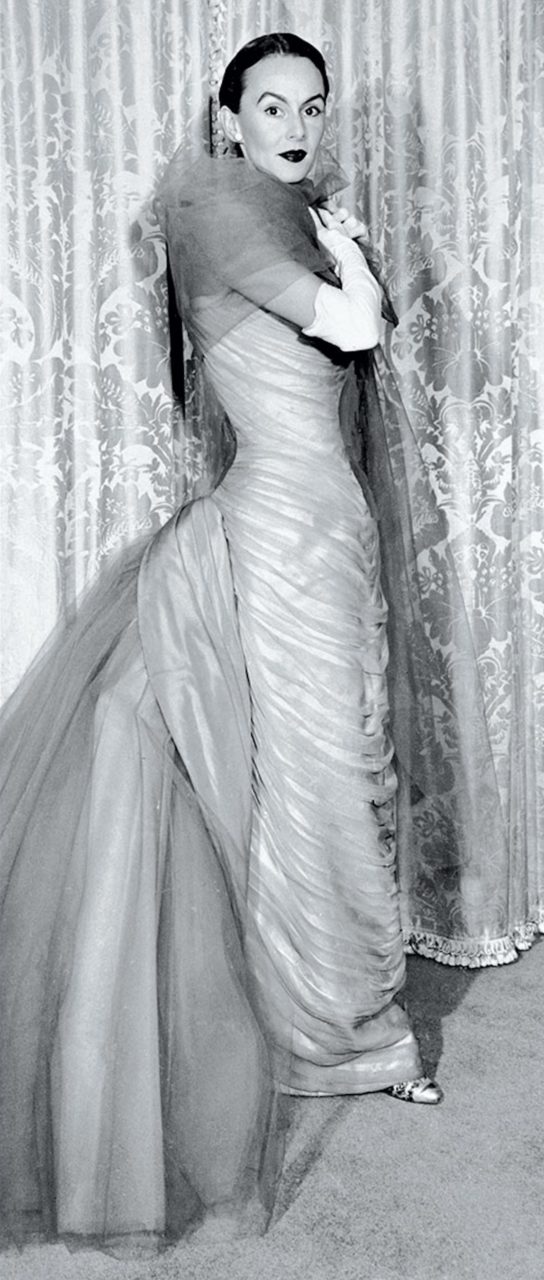

In 1957, the “Butterfly” gown was donated by Mrs. Dominique de Menil, renowned art collector, and patron of Charles James. Although this garment came from de Menil’s personal collection, the “Butterfly” gown was originally designed by James for Mrs. Austine Randolph Hearst in 1955. The gown made its very first appearance at the March of Dimes luncheon in 1955 and was modeled by Austine Hearst herself (Fig. 9). Charles James also designed his famous 1953 “Clover Leaf” dress for Mrs. Hearst to wear to President Eisenhower’s inauguration, which shows her influence and high status in society. With Mrs. Hearst wearing the “Butterfly” gown for the first time to a public event, the dress was meant to make an impact on viewers. Also, James held a fashion show at the convention of dry cleaners where a pale, yellow satin version of the “Butterfly” was modeled (Koda 45).

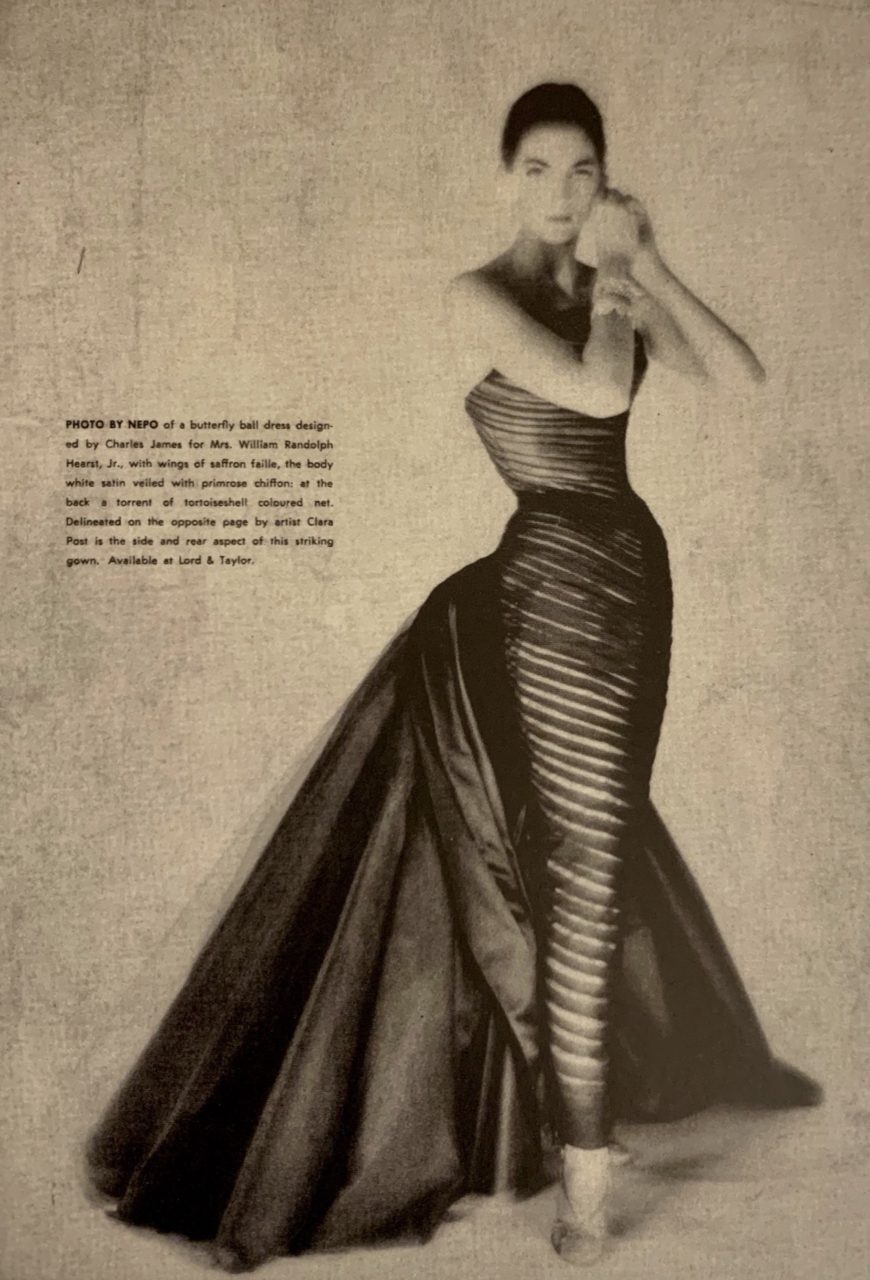

Charles James creations, like the “Butterfly”, evoked exuberant luxury and a high social status; however, this dress was also manufactured to be sold at Lord & Taylor (Fig. 10). This shows the importance of creating beautiful designs for wealthy society women while simultaneously providing garments at a more accessible location and price point (Koda 222).

Additionally, the “Butterfly” gown was photographed being worn by his wife, Nancy James (Fig. 11), and received news coverage in the Chicago American after being featured at the dry cleaners convention of 1955 (Fig. 12). It was featured in an article entitled “Night in Monte Carlo: The Imperial Ball,” in the March 1956 issue of Vogue in, where an attendee wore a black version of the “Butterfly” (Daves 184).

Fig. 9 - Photographer unknown. Austine Hearst wearing a "Butterfly" gown by Charles James, 1956. The Bettmann Archive. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 10 - Arik Nepo. A model wearing Mrs. William Randolph (Austine) Hearst Jr.'s version of the Butterfly gown. (Available at Lord & Taylor.), ca. 1955. Source: Charles James: Beyond Fashion (exhibition catalog)

Fig. 11 - Cecil Beaton (British, 1904–1980). Nancy James (wife of Charles James) modeling the "Butterfly" gown, 1954. The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby's. Source: Glamour

Fig. 12 - Photographer unknown. James' fashion at the 1955 convention of dry cleaners garnered full-page coverage in the Chicago American, March 5, 1955. Newspaper article. Source: Charles James: Beyond Fashion (exhibition catalog)

About the context

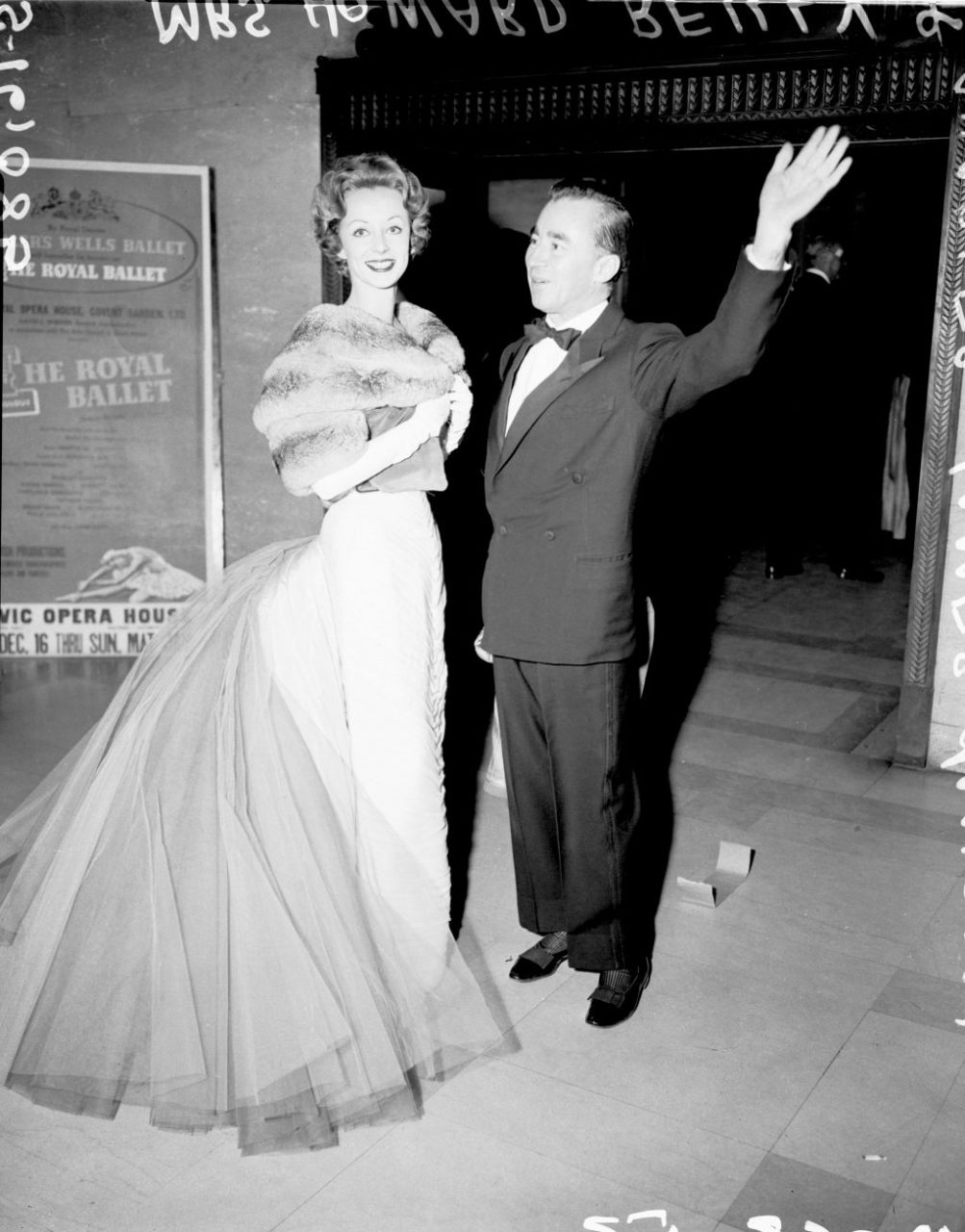

In the postwar world, consumption in all segments of society skyrocketed leading to the birth of “suburban style;” however, the 1950s were also emblematic of couture opulence, decadence, and luxury. Government aided programs, like America’s G.I. Bill of Rights, led to the redeployment of technology advancements, like television sets, into the homes of Americans. By 1950, over one million homes in the U.S. had television sets which led to an increase in the promotion of consumer goods. While France remained the leader in couture, America was very influential in terms of its pop culture, including films and music. Because of this, fashion was examined closely and took on an even more aspirational quality than it had previously. With Charles James designing evening wear for his fashionable celebrity clientele (Fig. 13), his garments gained visibility on a global scale by way of television, film, and the fashion press (Deihl & Cole).

Considering fashion journalism publications, such as Vogue, were at their peak, fashion photography and rules-driven social codes of dress impacted the practice fashionable dress. Time of day, location, age, and occasion dictated the appropriate garment to wear for any occasion, and evening wear played a significant role in the 1950s phenomenon of cocktail hour. A gown as extravagant as “Butterfly” embodied the idea of a separate dress code applicable only to couture garments which represented a select clientele, as opposed to the masses (Deihl & Cole 239).

Although similar to the fuller figure of the 1940s, the ideal body of the 1950s was reminiscent of the hourglass silhouette from the 19th century. A curvaceous figure that accentuated hyper-femininity and an extremely narrow waistline was deemed the fashionable silhouette throughout this decade (Fig. 14). The ideal body placed emphasis on lavishness, glamour, and shapeliness, which highlighted female sensibility as well as sensuality (Martin 51).

Following the arrival of Christian Dior’s “New Look” (Fig. 15) in February of 1947, nipped-in waists and voluminous skirts remained popular throughout the 1950s, and soon morphed into a straighter and slimmer silhouette (Reddy). When looking at James’ “Butterfly,” the waist remains the focal point with voluminous tulle evoking contrast between the narrowness of the wearer’s body and the drama of the bustle skirt. Indeed, this James garment emphasizes the feminine form with a sculpted sheath and exaggerated full skirt, showing his own opulent interpretation of the 1950s ideal body (“Butterfly”).

In order to create this fashionable silhouette, women wore highly structured shapewear to create a pointy bust, cinched waist, and defined hips. It is possible that a “corselet” or strapless bra was required for the “Butterfly” dress to define the bust as well as the waistline of the wearer, thus creating a tightly fitted form (Deihl & Cole 239).

Fig. 13 - Photographer unknown. Charles James And Mrs. Howard Reilly, December 17, 1957. Photograph. Chicago: Chicago History Museum. Source: Getty Images

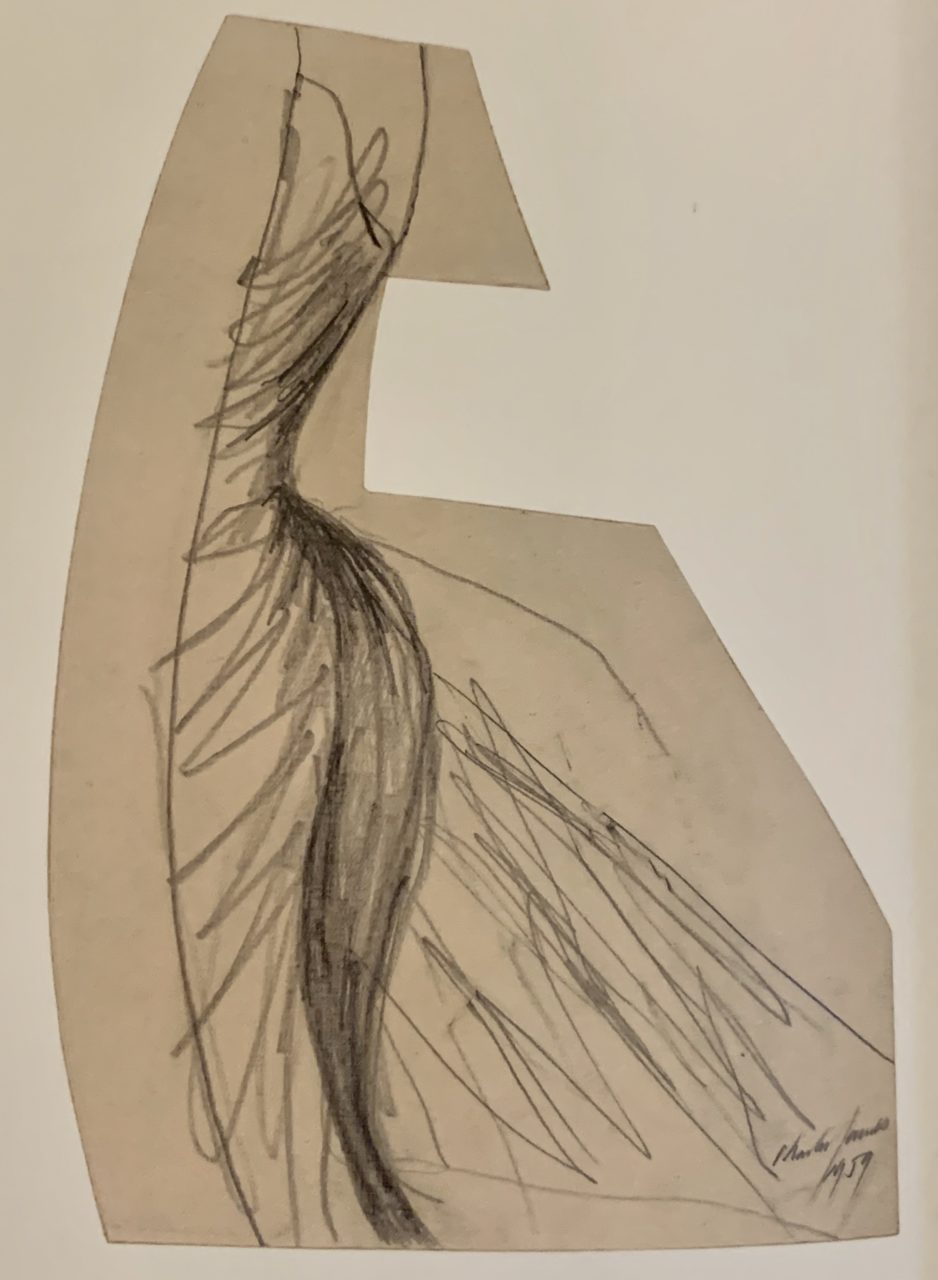

Fig. 14 - Charles James (American, 1906–1978). Sketch of "Butterfly" gown, 1959. Graphite on paper. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Google Books

Fig. 15 - Serge Balkin (1905–1990). Spring 1947: The New Look (Bar Suit) by Christian Dior, Vogue, April 1947. Condé Nast Archive. Source: Vogue

Its Legacy

T

his garment plays a significant role in the history of fashion, as it perfectly showcases James’ creative vision and architectural capabilities. Being one of the first strapless dresses in couture, the “Butterfly” ball gown also featured a heightened bust to create an elongated torso, which influenced designs over the following years. This voluminous gown embodied the golden age of couture, as well as the glamorous and feminine spirit of fashion during the 1950s.

Despite Charles James’ astonishing artistry and memorable designs, he isn’t considered a household name in fashion. However, with the Costume Institute’s 2014 exhibition “Charles James: Beyond Fashion,” his work gained more visibility to the public (Figs. 16-18). The exhibition was curated by Harold Koda, who was assisted by Andrew Bolton (Fig. 19). Attendees of the 2014 Met Gala honored Charles James—arriving in intricately detailed dresses featuring draping, tucking, elaborate trains, and overall timeless and glamorous silhouettes with a burst of creativity. Designer Nina Ricci designed a “Butterfly”-inspired dress for Alexa Chung with a body-conscious sculpted sheath and looser approach to tucking (Fig. 20). Perhaps the most straightforward interpretation of the “Butterfly” at the 2014 Met Gala was Donatella Versace’s olive body-hugging bodice and voluminous tulle train (Fig. 21).

Contemporary designer Zac Posen is heavily influenced by Charles James in his own work. By highlighting the female body with luxurious and sculptural designs, Posen’s work evokes a similar aesthetic to many of James’ masterpieces. Posen clearly drew inspiration from the “Butterfly” dress with his design worn by Katie Holmes at the 2019 Met Gala (Fig. 22). Constructed with layered tulle in a variation of purple and blue shades, the dress features a body-hugging sheath and voluminous tulle train. Not only did Posen take advantage of James’ practice of using different shades of the same textile, but the construction and silhouette is entirely reminiscent of James’ 1955 design of the “Butterfly.” Overall, Charles James’ “Butterfly, ball gown exhibits his superb dressmaking skills and true artistry, originality, and devotion to sculpting stunning garments that flatter the wearer and captivate the viewer.

Fig. 16 - Ruth Fremson (photographer). "Charles James: Beyond Fashion" Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014. Source: The New York Times

Fig. 17 - Photographer unknown. "Charles James: Beyond Fashion" Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014. Source: Models.com

Fig. 18 - Photographer unknown. The Butterfly gown on view in the "Charles James: Beyond Fashion" Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014. Photograph by Ruth Fremson. Source: The New York Times

Fig. 19 - Photographer unknown. Andrew Bolton and Harold Koda, curators of the "Charles James: Beyond Fashion" exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute, 2014. Source: The Wall Street Journal

Fig. 20 - Nina Ricci (French, founded 1932). Alexa Chung attends the 'Charles James: Beyond Fashion' Costume Institute Gala at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 5, 2014. Photograph by Axelle/Bauer-Griffin. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 22 - Zac Posen (American, born 1980). Katie Holmes attends The 2019 Met Gala Celebrating Camp: Notes on Fashion at Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 6, 2019. Photograph by Neilson Barnard. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 21 - Donatella Versace (Italian, born 1955). Designer Donatella Versace attends the "Charles James: Beyond Fashion" Costume Institute Gala at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, May 5, 2014. Photograph by Larry Busacca. Source: Getty Images

References:

- “Butterfly.” 1955. Metropolitan Museum of Art. (2009.300.816). https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/159388.

- Cole, Daniel James, and Nancy Deihl. The History of Modern Fashion from 1850. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/900012311.

- Coleman, Elizabeth Anne. “Charles James.” Valerie Steele, ed. The Berg Companion to Fashion. New York: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768814940.

- Daves, Jessica. “Night in Monte Carlo – The Imperial Ball.” Vogue (March 1956): 184. https://archive.vogue.com/article/1956/3/night-in-monte-carlo—the-imperial-ball

- Koda, Harold, Jan Glier Reeder, Sarah Scaturro, Glenn Petersen, and Ralph Rucci. Charles James: Beyond Fashion. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/900404806.

- Martin, Richard. “Fashion and the Car in the 1950s.” Journal of American Culture, vol. 20, issue 3 (Fall 1997): 51-66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-734X.1997.t01-1-00051.x

- Middleton, William. “‘There is a fantasy that propels his mind forward’: How the American Couturier Charles James Left His Sumptuous Mark on the de Menils.” System, no. 2 (Autumn–Winter 2013): 108-131. https://system-magazine.com/issue2/charles-james/

- Reddy, Karina. “1950-1959.” Fashion History Timeline. Fashion Institute of Technology, June 2, 2019. Accessed April 28, 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1950-1959/.

- Reeder, Jan Glier. “Charles James (1906-1978).” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000-present. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cjam/hd_cjam.htm