Since the mid-20th century, relations between Africa and China have grown stronger leading to a significant change in the mutual adaptation of fashion between both nations. A 21st century, Sino-African style has been formed by the intercultural meshing of traditional garments, textiles, and motifs.

China’s influence around the world is becoming more widespread and the country’s role as a soft power in Africa is a prime example. Aside from the political and economic reasons behind the power shift, there is another avenue of change happening in Africa’s fashion climate. As the Chinese population in Africa continues to increase along with China’s large economic involvement in Africa’s economy, local African dress styles are absorbing elements of Chinese culture to produce a novel and individualistic Sino-African look (Figs. 1-2).

Money is one of the driving forces fueling Sino-African fashion and one such example is China’s involvement in Mozambique, a country located on the eastern coast of South Africa. Lauren Baker describes China’s involvement in “Bridging Perceptions: China in Mozambique” (2019), saying:

“China is Mozambique’s largest bilateral creditor at $2.2 billion… China has forgiven and restructured debts that Mozambique owes on a semi-regular basis.”

Hence the term “debt-trap diplomacy” is often used by the Western world to describe China’s relationship with Africa. In return, China is able to gain more access to Mozambique’s natural resources, resources like gas, coal, and gold. On the other hand, the Mozambican government’s attitude toward China’s involvement is a stark contrast to the skepticism coming from the Western world. With an alliance with China, places like Mozambique benefit from “numerous large-scale infrastructure and construction projects, such as the newly finished Maputo-Katembe bridge across Maputo Bay,” and from “zero-tariff treatment” granted to a large percentage of imports, as explained by Von Pezold in “’It Is Good to Have Something Different’: Mutual Fashion Adaptation in the Context of Chinese Migration to Mozambique” in Asia Pacific Perspectives (Fall/Winter 2018-19).

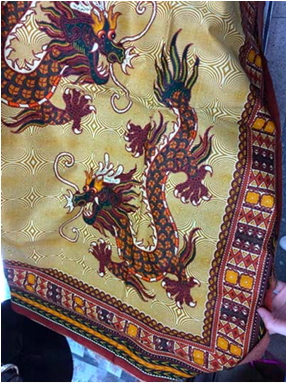

Fig. 1 - Designer unknown. Capulana with Chinese-dragon motif and African print border, undated. Cotton. Mozambique. Source: Asia Pacific Perspectives

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (African). Two Qipao-style dresses made out of fabrics customarily used in capulana dresses in a tailor stall at Mercado janet, undated. Cotton. Mozambique. Source: Asia Pacific Perspectives

Textile Production

As Sino-African relations strengthen, more Chinese people are migrating, either temporarily for work or permanently as residents, to Africa. The pockets of Chinese migrants and Chinese-owned storefronts are making soft waves in both the local market and the fashion scene. An example of this sort of change can be seen in the textile industry. Traditionally, the origin of a wax print cloth’s production was synonymous with the fabric’s value. As Nina Sylvanus explains in African Textiles from China (2011):

“A person’s social value or status was assessed and attached to the material value of the fabric itself. Around the 1940s the Dutch fabric (Vlisco) ranked highest in a fabric hierarchy that was organized by origin and quality, followed by English (ABC) wax cloth and, by the 1960s, by Ivorian, Ghanaian, and Nigerian wax prints, as well as lower-quality roller prints (fancy prints).”

So when wax prints made in China hit the market, the products were considered inferior in quality, and the authenticity was called into question. However, Sylvanus points out that various causes like democratization and devaluation of the currency allowed China to emerge as an alternative production center, initially as counterfeits of original Dutch prints and later as competitive brands like Hitarget, Phoenix, and Binta Wax. As Chinese wax prints increase in quality, the affordability attracts the consumers unable to purchase traditional Dutch fabric and helps mitigate the long-standing idea that Chinese products are “quick thing[s] (coisa rapida) which break in two days.”

Fashion

Along with the shift in the African textile market, a parallel evolution can be seen in fashion trends in some African countries, like Mozambique. One specific example is the evolving capulana styles in Mozambique; Pezold notes in “It Is Good to Have Something Different” (Fall/Winter 2018-19), that during her time in Mozambique she noticed certain elements of Chinese culture in the products being sold in African shops. For instance, figure 1 shows a capulana (a sarong-style dress popular in Mozambique and other parts of Africa) with a motif that closely resembles the traditional Chinese dragon motif along with a more African-styled border along the edge of the garment. The color choice is more muted than what the Chinese dragon would usually be depicted as; instead an earthier and more traditionally African color story is used. And in figure 2, a tailor shop is displaying two dresses that illustrate the fusion of Chinese and African culture. While the hemline, silhouette, and neckline align with a qipao-style dress, the fabrication uses a textile traditionally used in capulanas which makes the garment more recognizable and wearable to the Mozambique consumer. In both cases, traditional capulana styles are being combined with Chinese elements to produce individualistic looks that satisfy local dressing needs. As Nadia, a local Mozambican, said, “a capulana most importantly must be a novelty (novidade).”

Fashion’s abiding desire for novelty is one of the reasons why Chinese influences are finding their way into African fashion. Ladunni Lambo is a Nigerian designer who founded a ready-to-wear collection that encapsulates her love for her culture. The brand debuted with a collection called A Wife for Nana, which told the story of a woman forced into an arranged marriage. The collection included many pieces that combined modern and traditional fashion elements. Lambo also incorporated subtle Chinese components into her designs. Figure 3 shows a sumptuous blue dress that has a side split and form-fitting silhouette that looks like a modern interpretation of a traditional qipao. Rather than a placket-like side split in a qipao, Lambo’s dress has no true side seam and instead, uses a crisscrossing lacing system. Another piece in her collection (Fig. 4) is a two-piece ensemble that uses appliqués with floral motifs resembling Chinese rose flowers. The pants feature a closure at the center front and at the bottom edge of the pants that is also reminiscent of traditional Chinese knotted button closures. On the other hand, the bright salmon pink of the ensemble is a bold color choice that is more customary in contemporary African fashion.

Fig. 3 - Ladunni Lambo (West African). Dress from "A Wife for Nana" collection, 2016. Nigeria. Source: Globetrotter Magazine

Fig. 4 - Ladunni Lambo (West African). Pantsuit from "A Wife for Nana" collection, 2016. Nigeria. Source: Globetrotter Magazine

To understand these sorts of inspirations and exchanges, Joanne Eicher and Tonye Erekosima’s definition of “cultural authenticiation” (1981), which they divide into four stages, is useful:

- Selection – “an object, idea, or technique is selected out of many possibilities presented by another culture;”

- Characterization – “the form is renamed or somehow translated to fit the new culture;”

- Incorporation – “it comes to satisfy a new need in society;”

- Transformation – “the form is completely integrated and no longer seems foreign.” (Akou)

Fig. 5 - Marianne Fassler (South African). Outerwear look, SS 2018. Johannesburg. Source: Marianne Fassler

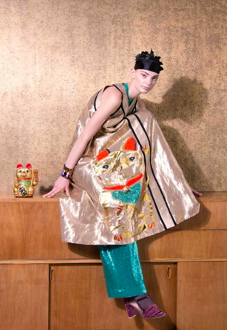

A couture example of authentication of Chinese culture in African fashion is Marianne Fassler’s Spring/Summer 2018 collection. As a South African who produces fashion made in Africa, her work incorporates Chinese influences in a bold and direct manner without sacrificing integral elements of South African style. Her SS18 collection included a beautiful outerwear piece (Fig. 5) that boasts a graphic Chinese dragon-like creature in the back. However, instead of implementing traditional Chinese colors like green, gold, or red, Fassler made the choice of using shades more popular in African prints. In another piece (Fig. 6), her garment has a neckline that resembles the closed robe style of a shenyi, which was a style worn by the Chinese during the Han dynasty. Fassler also showcases a graphic fortune cat on the bottom right of her dress design (the same garment is shown in a different photoshoot in figure 7). While the cat motif originated from Japan, the fortune cat is extremely popular in China as a welcomer of luck and the motif’s incorporation illustrates how China’s involvement in African markets is affecting not only the economy but also the symbolism used in fashion. The lucky icon is also used in another one of her designs (Fig. 8) in the center front and contrasts against the otherwise all-black garment. In this look, the cat graphic serves as a modesty piece, as everything underneath is sheer. The skirt’s trim and bottom section has patterns and shapes that are more in line with African textile design. The melding of two cultures in Fassler’s SS18 collection creates unique looks that are unlike customary fashion styles in China and South Africa.

Fig. 6 - Marianne Fassler (South African). Dress, SS 2018. Johannesburg. Source: Marianne Fassler

Fig. 7 - Marianne Fassler (South African). Dress, SS 2018. Johannesburg. Source: Marianne Fassler

Fig. 8 - Marianne Fassler (South African). Top and skirt, SS 2018. Johannesburg. Source: Marianne Fassler

Western Influence

What makes Chinese influence on African fashion interesting is the milder scope of impact in comparison to the aggressive changes made under the influence of other cultures like the Portuguese in previous centuries. Portugal colonized parts of Africa in the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries primarily for resources and for missionary work. Marie-Amy Mbow in Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Prehistory to Colonialism (2010) describes how dress practices of the West African elite changed, often adopting Portuguese styles of dressing after converting to Christianity:

“After conversion to Christianity, the elite members of the court began to dress themselves in the style of the Portuguese, with coats, capes, scarlet cardigans, silk hats or bonnets, velvet and leather sandals, Portuguese-style boots, and large swords. The women of the court covered their heads with veils and black velvet bonnets decorated with jewels.”

Portuguese presence caused West African fashion to shift from lighter dressed styles (which accommodated the weather) to layered looks that appeased Western ideas of modesty. While some incorporated European design elements into their pre-colonial way of dressing, the upper echelons of courts in many African nations embraced the styles of the Portuguese as a show of power and prestige. Then in the eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, a similar fashion shift can be seen as Europeans became more involved in colonial rule. Mbow describes how in French-controlled Senegal “signares and mulatto women adopted European clothes, stockings, and shoes” and they embroidered pagnes (a form of wrap dress) with designs that mimicked French styles. These women were the trendsetters of African fashion at the time and promoted European fashion in their own looks that moved further away from earlier African dress styles.

In comparison, China’s soft power impact on African fashion favors the concept of gradualism, where subtle changes are made to tweak preexisting styles. As Pezold explains in “It Is Good to Have Something Different” (Fall/Winter 2018-2019), world fashion (like jeans and T-shirts) acts as a mediator between Chinese and African styles by making “foreign fashion elements lose a part of their strangeness.” So when the Chinese population in Mozambique wears local accessories and textiles, and when the African community adopts forms and motifs of Chinese dress into traditional Mozambican fashion, the subtle mutual exchanges “fit in more harmoniously.” There are also the concepts of “not too African” and “not too Chinese” prevalent with Mozambican consumers.

In Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, a “Chinese collar” (the neckline of a qipao) is a design element popular in both menswear and womenswear and the detail shows how consumers strike a balance in their wardrobes. Figure 9 shows a Mozambican woman wearing a red top with that Chinese design detail. The woman’s “Chinese collar” top was actually an altered qipao style dress that was too short (in terms of Mozambican standards where anything above the knees is considered indecent by some). Since most off-the-rack Chinese garments are only offered in a small size, many Mozambicans alter their purchases or order tailor-made versions. On the other hand, the Chinese population in Mozambique also follows the same concept of “not too much.” Instead of adopting local fashion silhouettes, many Chinese prefer capulanas “tailored in a cosmopolitan designs” so that the look retains their favored design elements while allowing them to have a Mozambican aesthetic.

Through a gradual shift, China is slowly but steadily becoming more of an influence in Africa’s fashion scene. As the Chinese population in Africa grows, and the relationship between Africa and China evolves, the mutual adaptation and cultural authentication of fashion between the two cultures will likely only become more prevalent over time.

Fig. 9 - Johanna Von Pezold (Mozambican). Mozambican woman wearing top with Chinese collar, FW 2018-19. Maputo. Source: Asia Pacific Perspectives

References:

- Akou, Heather Marie. “Colonialism to Independence.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Africa, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Doran H. Ross, 44–50. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. Accessed July 16, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch1007.

- Baker, Lauren. “Bridging Perceptions: China in Mozambique.” MacroPolo. Paulson Institute, August 27, 2019. https://macropolo.org/analysis/china-mozambique-elite-perceptions/.

- Mbow, Marie-Amy. “Prehistory to Colonialism.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Africa, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Doran H. Ross, 35–43. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. Accessed May 01, 2021. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/746490838

- Sylvanus, Nina. “African Print Textiles from China.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Africa, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Doran H. Ross. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2010. Accessed April 21, 2021. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8004695228.

- Vollmer, John E. “Cultural Authentication in Dress.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Global Perspectives, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Phyllis G. Tortora, 69–76. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Accessed July 16, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch10009.

- Von Pezold, Johanna. “’It Is Good to Have Something Different’: Mutual Fashion Adaptation in the Context of Chinese Migration to Mozambique.” Asia Pacific Perspectives Journal 16, no. 1 (Fall/Winter 2018-19). https://www.usfca.edu/center-asia-pacific/perspectives/v16n1/von-pezold.