The American Beauty dress embodies the dreamlike aesthetic of Ann Lowe, a frequently overlooked Black designer who was integral to the history of American fashion. This 1966-1967 gown highlights Lowe’s creativity, while still reflecting the simplified silhouettes of the 60s.

About the Look

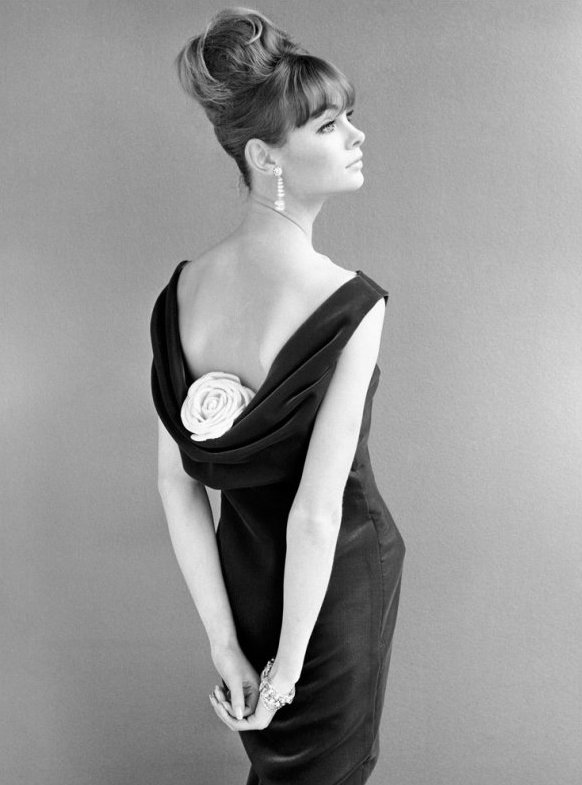

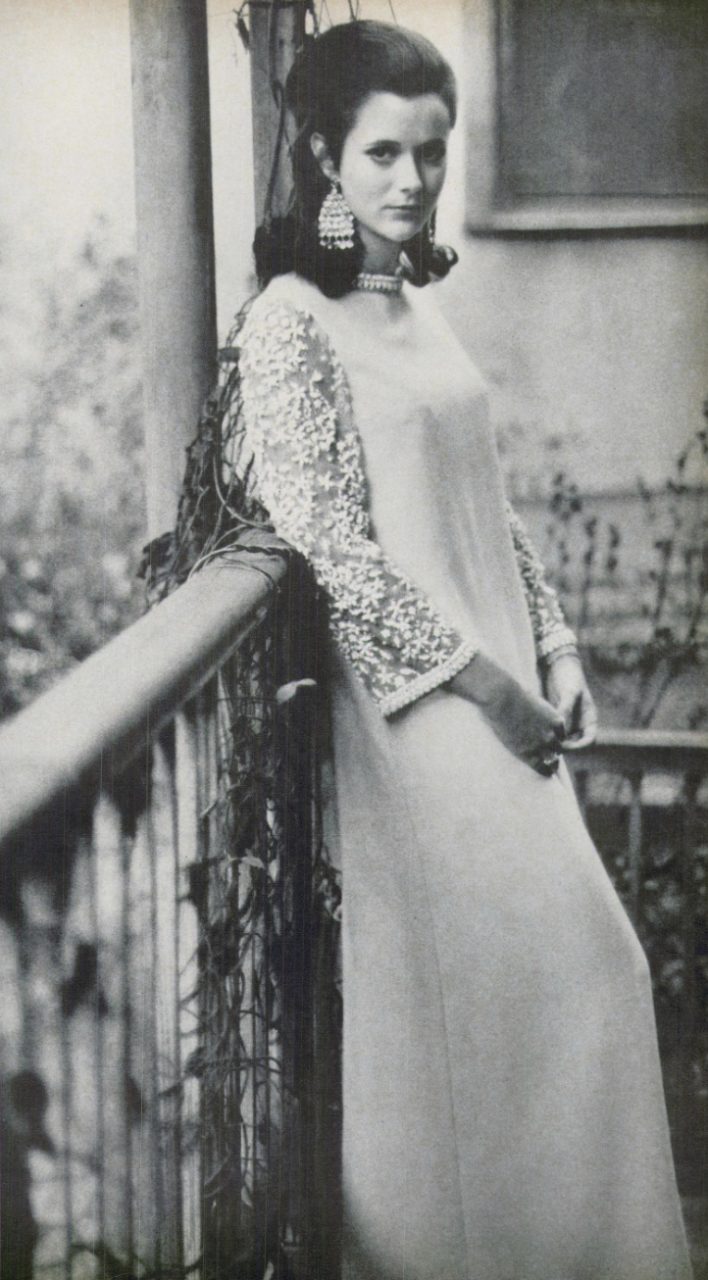

This 1966-67 dress shows off the elegant taste of its designer, Ann Lowe. It is constructed out of ivory silk faille. The neckline of the dress gently scoops in the front and descends in the back, which daringly exposes the wearer’s shoulder blades (Fig. 1). The gown contours the bust and features an empire waistline that swoops to the natural waist in the rear (Fig. 2). The full-bodied fabric undulates to the floor from a series of small pleats in the back of the skirt. The silhouette of the dress reflects 60s style; the narrow skirt creates a clean line from the waistline to the hem (Fig. 3).

Lowe decorated the gown with flourishing vines and flowers made from silk—a signature design element. The dress is often referred to as the American Beauty dress, as the silk flowers resemble the American Beauty variety of rose. The rose and baby pink flowers are almost surreal; they are imbued with so much life that they appear as if they are about to grow beyond the boundaries of the gown. The embellishments are impactful and graphic. The snaking green vines have meticulously-rendered leaves and veins, and the blooms are shaped with delicate pleats.

As a result of Lowe’s mastery of the complex architecture of evening wear, the dress appears almost effortless. Boning, cups, and several lines of elastic support the wearer’s bust. It has an interior waistband made from grosgrain. The dress is lined with a knit and has an interior petticoat to hold out the shape of the hem (Smithsonian Institute). The interior of a Lowe gown with a similar style of construction can be seen in figure 4.

The dress belonged to an American named Barbara Baldwin Dowd. It was worn as a debutante dress. As reflected by the gown’s tiny 23-inch waist, it was intended for a teenager. Over the course of her career, Lowe designed many debutante and bridal gowns, including Jackie Kennedy’s wedding dress.

Fig. 1 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). American Beauty dress, 1966-1967. Silk, tulle, linen, metal, and elastic. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2007.3.19. Gift of the Black Fashion Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Source: NMAAHC

Fig. 2 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). American Beauty dress, 1966-1967. Silk, tulle, linen, metal, and elastic. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2007.3.19. Gift of the Black Fashion Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Source: NMAAHC

Fig. 3 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). American Beauty dress, 1966-1967. Silk, tulle, linen, metal, and elastic. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2007.3.19. Gift of the Black Fashion Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Source: NMAAHC

Fig. 4 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Evening dress, 1962-1964. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.260.2. Gift of Mrs. Carll Tucker Jr., 1979. Source: The Met

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). American Beauty dress, 1966-1967. Silk, tulle, linen, metal, and elastic. Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2007.3.19. Gift of the Black Fashion Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Source: NMAAHC

About the designer

Ann Lowe (Fig. 5) had a reputation for designing dreamlike, almost fairy-tale dresses (Congdon 75). Those who worked with her during her career remarked upon the elegance of her designs. Her artistic vision has been compared with that of Chanel or Dior (Congdon 76). Lowe was passionate about the art of dressmaking and her gowns were of exceedingly high-quality (Davis and Grabowski). Polly Duxbury, the wearer of a gown similar to the American Beauty dress, described:

“the fit is absolutely glorious—it’s like your skin. The slip has tulle along the hem, which gives it shape. This kind of really detailed, really high-end work is very time-intensive.” (Davis and Grabowski)

During Lowe’s childhood, she was taught how to execute fine sewing by her mother and grandmother (Powell 3). As a teenager, Lowe was convinced by a wealthy socialite to move to Tampa, Florida. There, she built an extensive list of wealthy and elite clientele (Kwateng-Clark). In 1928, Lowe permanently moved to New York City (Way 119). While her career in New York had its ups and downs, Lowe was eventually highly successful and catered to a list of clients that were high on the social register (Powell 39). Today, she is known for being the designer of Jaqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress (Fig. 6); however, at the time it was made, Lowe went uncredited (Lee). She also designed the dress seen in figure 7, which was worn by actress Olivia de Havilland to the Oscars in 1947.

Lowe had to face nearly insurmountable odds to succeed. She was born in 1898 and raised in Alabama during the Jim Crow era. As a Black woman, she was excluded from baseline educational opportunities, business resources, and networks that were only accessible to white members of the community (Powell 4). Her mother passed away when she was sixteen, leaving Lowe to continue her family’s business in dressmaking (Way 118). After achieving success in Tampa, she initially left to pursue higher education as a designer. Even though New York was supposedly more liberal than the South, Lowe was forced to work in a segregated classroom, as the other students refused to work in the same room as her (Powell 12). She also struggled with two unsupportive husbands (Congdon 75, Powell 35), and the near loss of her eyesight from glaucoma (Congdon 75)

Fig. 5 - Photographer unknown. Ann Lowe, date unknown. Source: Tallahassee Democrat

Fig. 6 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Jacqueline Kennedy’s Wedding dress, 1953. Silk taffeta. Source: FIT Fashion History Timeline

Fig. 7 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Olivia de Havilland's Academy Awards gown, 1947. Source: New York Post

About the context

Another popular feature of this style of dress is the empire waist. The shape was fashionably youthful and fresh. In a 1964 New York Times article entitled “Waists Are High On Bridal Gowns”, they describe the trend, “Necklines are gently scooped or squared, waistlines are lightly elevated, and skirts are narrow but rounded over the hips” (20). The New York Times also mentions their prevalence in London high fashion in 1967, writing, “A climbing waistline was the single common factor in the highly different collections [designers] showed here this week.” One can see how the shape rose in prevalence during the mid-60s.

Fig. 8 - Madame Grès (French, 1903–1993). Evening dress, 1966-1967. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.138.2. Gift of Mrs. Mary Sykes Cahan, 1973. Source: The Met

Fig. 9 - Mainboucher (French, 1890–1976). Evening dress, 1964. Silk, metallic. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.7761. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Frank K. Sanders, Jr., 1970. Source: The Met

Fig. 10 - Yves Saint Laurent (French, 1936-2008). Evening dress, 1965. Zurich: Swiss National Museum. Source: Pinterest

Gowns of this shape frequently have low scoop necklines. The Lowe dress would have highlighted the wearer’s décolletage and upper back. Lowe tried to modernize the look of the debutante dress beyond its old-fashioned roots. A New York Times article from 1967 that features the American Beauty dress states:

“When a mother asked Mrs. Lowe why the fabric in back was almost nonexistent, the designer, who wears a black fedora while she works, said: ‘To save my beautiful dresses; I want to keep the hands of the boys from getting them so dirty when they dance.’” (42)

This daring style could be found in the upper echelons of high fashion. In 1965, Yves Saint Laurent created a dress with a similar silhouette (Fig. 10). Jean Shrimpton, a well-known model, was photographed wearing a bare-backed dress with a rose in the early 60s (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 - John French (English, 1907-1966). Jean Shrimpton in an evening dress, 1960s. London: Victoria and Albert. Source: King & McGaw

Fig. 12 - Karen Stark for Harvey Berin (1921-1970). Town and Country, Vol. 121, iss. 4532, (Mar. 1967). Source: ProQuest

Fig. 13 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Evening dress, 1967. Silk, metal, cotton, velvet. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 2017.0326.01. Gift of Polly Carver 1967. Source: NMAH

What sets the American Beauty gown apart from others of this decade are the animated appliqué roses and vines made from silk. Floral embellishments made several appearances in contemporary fashion publications; however, they were usually more flattened and subdued in comparison to the Lowe dress. Women’s Wear Daily, a popular trade publication, remarks that floral appliqués frequently appeared in retail advertisements in April 1964; they’re also shown in Town and Country in March 1967 (Fig. 12).

Large floral embellishments with technicolor hues are a hallmark of many of Lowe’s creations. Lowe’s floral designs were informed by her childhood spent learning to sew from her mother and grandmother. Surrounded by the scraps from their work, Ann would piece together magnificent blossoms from the offshoots that fell to the floor (Powell 3). The blooms became a theme throughout Lowe’s adult work. In this 1967 gown (Fig. 13), fuchsia velvet roses burst from the waistline. The 1968 dress seen in figure 14 has chiffon chrysanthemums dancing around the hem. Compared to other debutante dresses from the 60s, Lowe’s gowns shared a boldness that few could match.

Throughout Lowe’s career in New York, she frequently created debutante dresses (Powell 33). Her clientele was almost exclusively white and of the official New York society register (Powell 39). Lowe worked tirelessly to escape discrimination, but by necessity, she created gowns that were used to reproduce class boundaries. While debutante balls can be seen as a rite of passage, the traditional intent was to promote endogamous marriage and to reinforce that members of high society would continue to socialize within the boundaries of the elite (Haynes, ch. 3). As an African American woman, Lowe would have been largely excluded from these events, although she was the source of the elite’s ritual costume. The American Beauty gown was intended to represent a very specific version of American beauty, one which was overwhelmingly white and wealthy.

Despite the small amount of press that Lowe received throughout her lifetime, her elegant designs are integral to the history of American fashion. Her work reflects the trends of the 60s while still developing a unique dreamlike aesthetic, and she was able to show her personality and imagination through embellishment and craftsmanship.

Fig. 14 - Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Evening dress, ca. 1968. Cotton, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980.433.3. Gift of Florence J. Cowell, 1980. Source: The Met

References:

-

Congdon Jr., Thomas B. 1964. Saturday Evening Post 237 (44): 74. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2055/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=18021155&site=ehost-live.

-

Davis, Nancy, and Amelia Grabowski. “Sewing for Joy: Ann Lowe.” National Museum of American History, March 9, 2018. https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/lowe.

-

Haynes, Michaele Thurgood. “The Construction and Maintenance of Class and Gender Roles.” In Dressing Up Debutantes: Pageantry and Glitz in Texas, 51–91. Dress, Body, Culture. Oxford: Berg, 1998. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/9780857854063/DRESSDEBS0005.

-

“IN LONDON: BRINGING BACK THE EMPIRE WAIST.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Jan 19, 1967. https://nyti.ms/2Z8mchm.

- National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Dress Designed by Ann Lowe,” n.d. https://nmaahc.si.edu/object/nmaahc_2007.3.19.

-

Powell, Margaret. “The Life and Work of Ann Lowe: Rediscovering ‘Society’s Best Kept Secret.’” Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts, The Corcoran College of Art + Design, 2012. https://www.worldcat.org/title/life-and-work-of-ann-lowe-rediscovering-societys-best-kept-secret/oclc/820747062.

-

“Waists are High on Bridal Gowns.” New York Times (1923-Current File), Jan 17, 1964.https://nyti.ms/38BLAzd.

-

Warren, Virginia. “For Debutantes: Bare Backs.” New York Times. November 17, 1967. https://nyti.ms/2BJNYIa

-

Way, Elizabeth. 2015. “Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe: Recovering an African American Fashion Legacy That Clothed the American Elite.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture 19 (1): 115–41. doi:10.2752/175174115X14113933306905