About the Designer

Ann Lowe was born into a lineage of seamstresses who had established their own dressmaking business in Montgomery, Alabama. Her grandmother was a formerly enslaved dressmaker, and her mother specialized in embroidery. When Lowe was sixteen, her mother passed away suddenly. In her mother’s place, Lowe completed a high profile order from the governor’s wife that established her as the new head of the family business.

Lowe left her husband and moved to Florida with her son, becoming a live-in dressmaker for a socialite for ten years. In 1917, she traveled to New York City to attend sewing courses. As the only Black student, she was segregated to a separate room away from her peers. She permanently moved to New York City in 1928.

Lowe’s client network was integral to her success. She became famous among the wealthy American elite for her one-of-a-kind gowns made of fine fabric and handiwork, often evoking floral motifs. Lowe specialized in debutante gowns, and pleased clients would return to her for their wedding dresses. In her research, Museum at FIT curator Elizabeth Way describes the couture-quality techniques emblematic of Lowe’s craftsmanship, which included “gathered tulle and canvas to hold out hems, lace seam bindings, hand sewn organza facings, and weights to promote proper hang.” In 1950, Lowe opened her stand-alone business, “Ann Lowe’s Gowns” in New York City.

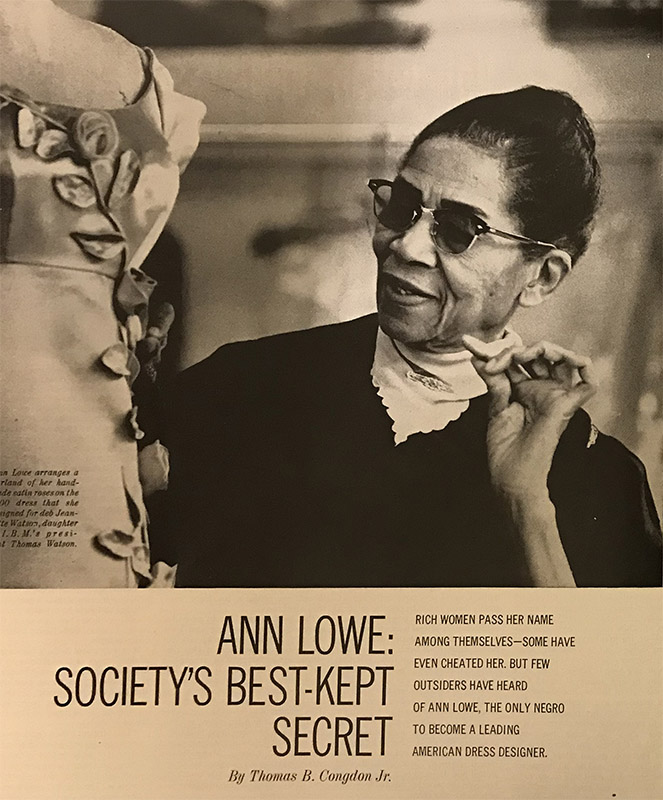

Photographer unknown. Ebony Magazine, Ann Lowe in her Madison Avenue salon, December 1966. 137. Source: Ebony

"Ann Lowe: Society's Best-Kept Secret". Saturday Evening Post, 1964. Source: Smithsonian

In 1953, Ann Lowe was chosen to create the dresses for the entire bridal party of Jacqueline Bouvier’s wedding to senator John F. Kennedy (see Timeline essay below). Ten days before the wedding, there was a flood in Lowe’s studio, destroying two months’ worth of work. Lowe enlisted extra help, reconstructed the dresses, and absorbed the cost. The wedding gown received publicity, but the press did not credit Lowe at the time, referring to her as “a colored dressmaker.”

Although she excelled at dressmaking and designed for an elite clientele, Lowe was paid less than white designers for her custom design work. Upon the death of her son and business partner in 1958, she had difficulty making ends meet, ultimately declaring bankruptcy in 1962. An anonymous benefactor, thought to be Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, paid off the debt Lowe had incurred from medical and business expenses.

No longer “society’s best kept secret” as the Saturday Evening Post called her, Lowe is now recognized as a pioneering African American couturier. Her pieces are preserved in renowned museum collections including the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of the City of New York, and The Museum at FIT.

Timeline Essays (Click the images to read more):

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Jacqueline Kennedy’s Wedding dress, 1953. Silk taffeta. Source: FIT Fashion History Timeline

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Dress designed by Ann Lowe, 1966-1967. Silk, tulle, linen, metal, and elastic. Washington: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2007.3.19. Gift of the Black Fashion Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Source: Smithsonian

GALLERY

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Debutante gown detail, ca. 1956. Silk organza, silk taffeta, applied stemmed roses. New York: The Museum of the City of New York, 2009.2.1. Source: MCNY

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Ball gown in Chantilly lace over silver-white duchesse silk satin, 1957. New York: Museum of the City of New York, 2009.2.2. Source: MCNY

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Evening dress, ca. 1960. Nylon, metallic thread, silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.144. Gift of Lucy Curley Joyce Brennen, 1979. Source: The Met

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Dress for Barbara Baldwin Dowd, 1966-67. Brocaded silk taffeta, silk chiffon, synthetic fiber, buckram, elastic and metal fasteners; 139.7 × 116.8 cm (55 × 46 in). Washington: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, 2007.3.23. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift of the Black Fashion Museum founded by Lois K. Alexander-Lane. Source: NMAAHC

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Debutante ball dress for Pauline "Polly" Carver Duxbury, 1967. Source: Smithsonian

Ann Lowe (American, 1898-1981). Wedding dress, 1968. Silk peau de soie, cotton, synthetic, silk satin. New York: The Museum at FIT, 2009.70.2. Gift of Judith A Tabler, 2009. Source: MFIT

To Learn More:

- Congdon Jr., Thomas B. 1964. Saturday Evening Post 237 (44): 74. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2055/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=18021155&site=ehost-live.

- Davis, Nancy, and Amelia Grabowski. “Sewing for Joy: Ann Lowe.” National Museum of American History, March 9, 2018. https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/lowe.

- Powell, Margaret. “The Life and Work of Ann Lowe: Rediscovering ‘Society’s Best Kept Secret.’” Master of Arts in the History of Decorative Arts, The Corcoran College of Art + Design, 2012. https://www.worldcat.org/title/life-and-work-of-ann-lowe-rediscovering-societys-best-kept-secret/oclc/820747062.

- Way, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe: Recovering an African American Fashion Legacy That Clothed the American Elite.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body & Culture 19, no. 1 (2015): 115–41. doi:10.2752/175174115X14113933306905

- Way, Elizabeth. “From Dressmakers to Designers” Filmed February 6, 2017 at The Museum at FIT Black Fashion Designers Symposium, New York, NY. Video, 17:18. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQhxUtAXH3Q