Rudi Gernreich’s 1970 caftan reflects the designer’s politics and his tireless effort toward creating genderless clothing. The piece features his characteristic loose silhouette as well as his technique of using patterns to de-accentuate the assumed gender of the wearer.

About the Look

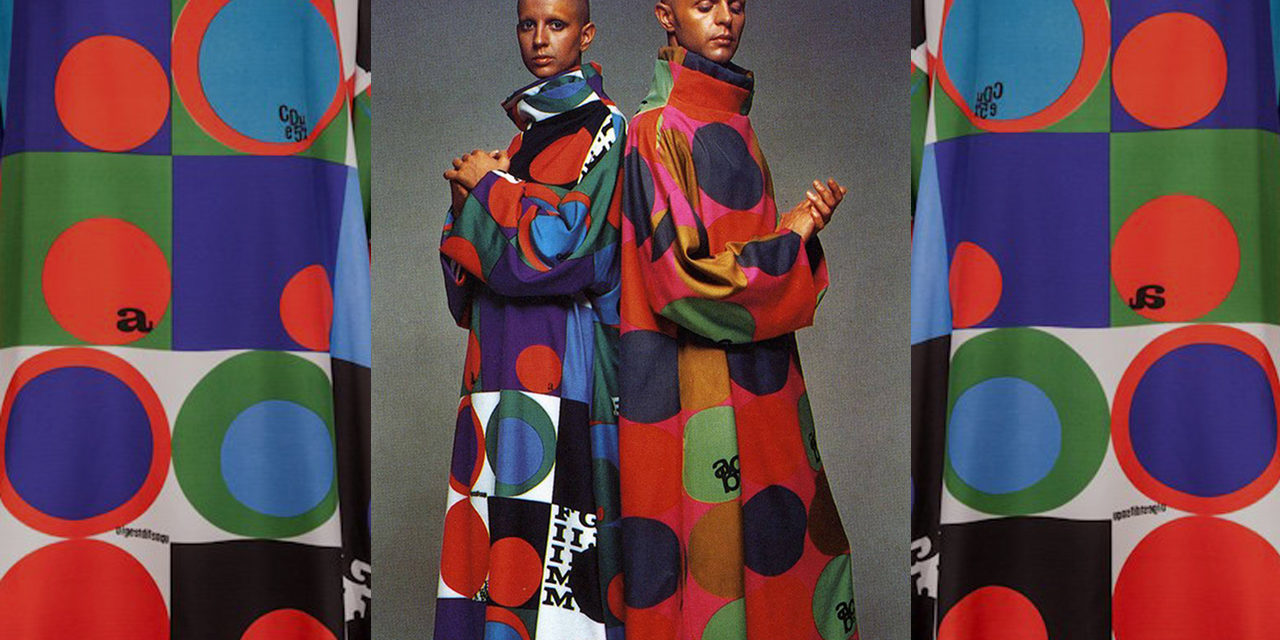

This 1970 caftan was a part of Rudi Gernreich’s Unisex Collection that he showed at Expo ‘70, the world’s fair held in Osaka, Japan (FIDM Museum). The floor-length long-sleeve silk garment is loosely fitted and has a wide turtleneck that leaves space on either side of the wearer’s neck (see Fig. 1). The piece is covered in an Op-Art-inspired design of purple, red, blue, green, black, and white shapes along with various sizes and fonts of text. Gernreich’s goal for his design was ‘maximum comfort’ and in his unisex fashions, he ultimately wished to blur the lines between genders. The designer noted that “If a body can no longer be accentuated, it should be abstracted” (FIDM Museum). Through the use of contrasting colors and bold patterning, Gernreich sought to emphasize utility, comfort, and the notion that the clothing we wear didn’t need to fall under arbitrary divisions based on gender.

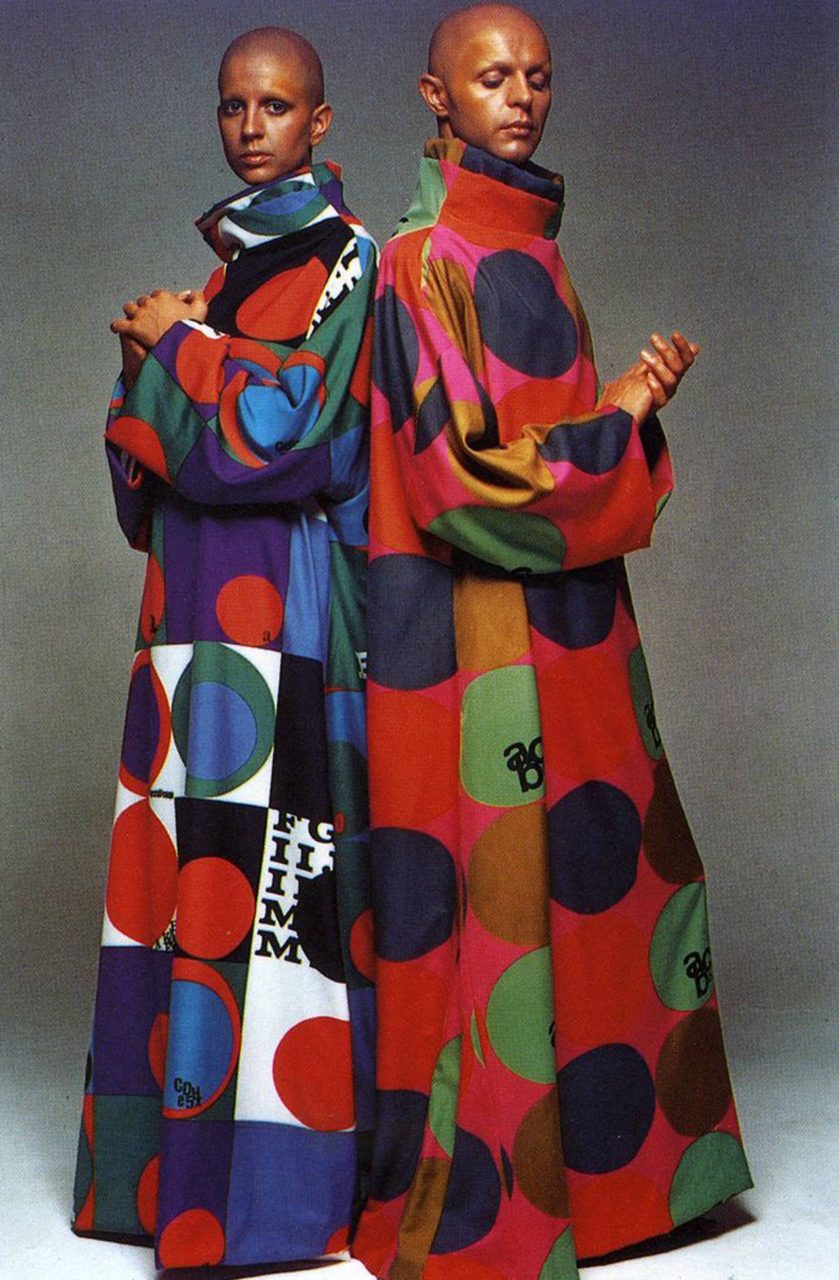

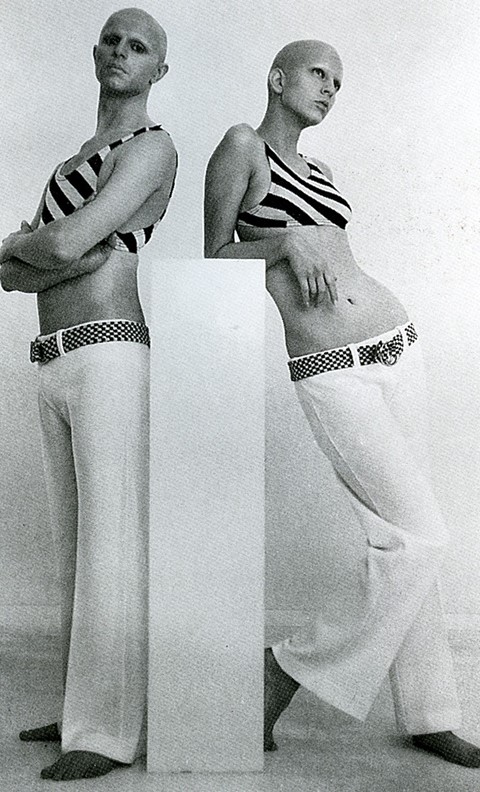

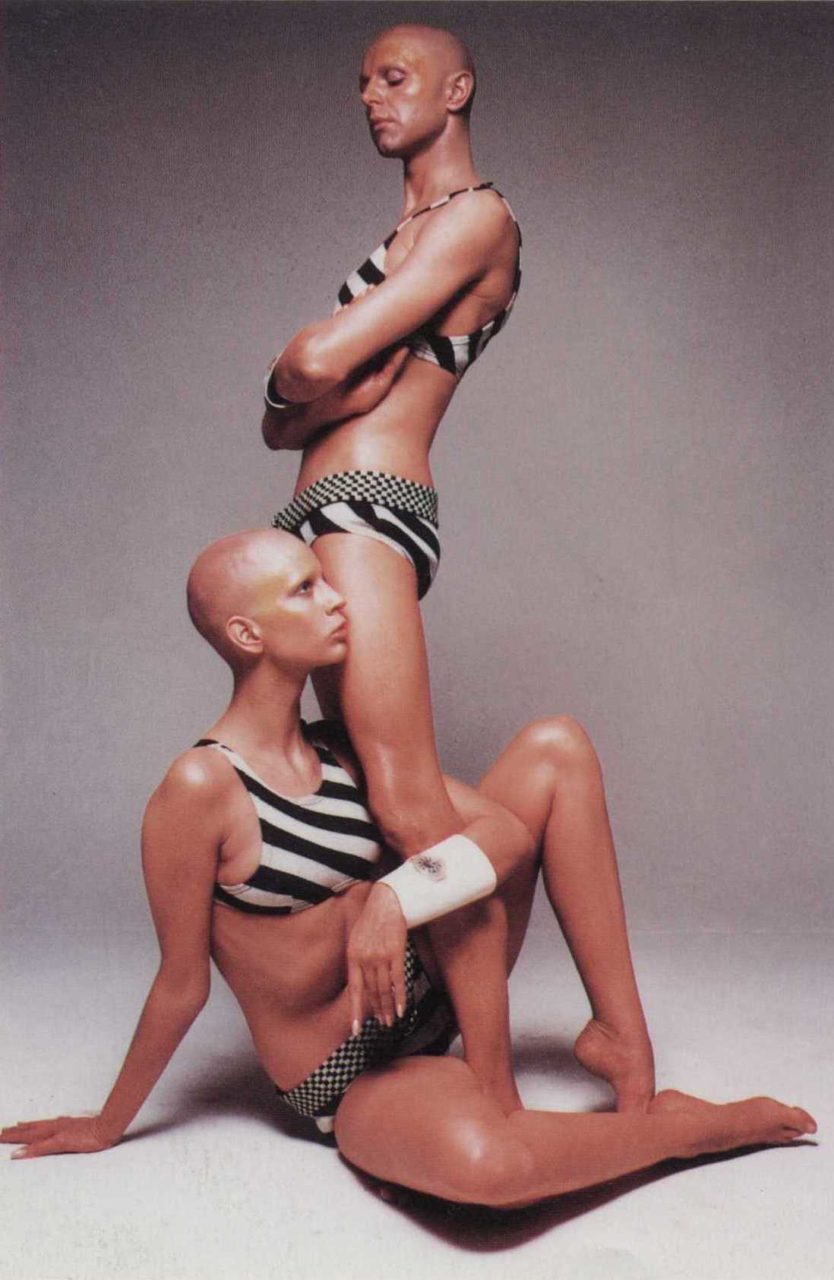

To Gernreich, the future of fashion was unisex. In photographing the designs for the collection, the designer utilized a male and female model who were both shaved completely of body hair and made to wear identical garments (Feldere) (see Figs. 2-3). In order for his design to be represented properly, he believed it would work best if the models were ‘stripped of their gender signifiers’ (Lundén). The photographs represent that Gernreich truly was a proponent of gender-neutral fashion, arguing that an individual’s‘ gender’ as delegated by societal norms didn’t need to be subsumed by clothing as well. The caftan as a concept was to be a sort of ‘uniform’ that through its unique coloring and wide silhouette would obscure the wearer’s form and help to question what gender truly was as a concept (Feldere). In a world in which fashion was so dedicated to the gender binary, Rudi’s notion of gender-less fashion was revolutionary though there was a push in the late 1960s towards more androgynous wear.

Fig. 1 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Caftan, 1970. Silk. Los Angeles: Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising Museum, G85.331.17. Bequest of the Rudi Gernreich Estate. Source: 1st Dibs

Fig. 2 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Tom Boome and Renée Holt in 'The Unisex Collection', 1970. Source: Another Mag

Fig. 3 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1980). Tom Boome and Renée Holt in 'The Unisex Collection', 1970. Source: The Rudi Gernreich Book

The piece itself features design choices present in Gernreich’s work throughout his long career. Gernreich was a proponent of unique color combinations that often appeared awkward that he would pair with graphic motifs, creating contrast in every part of the garment (Feldere). As a creator, he began studying under the dancer Lester Horton, therefore since the inception of his brand he worked to emphasize movement in his designs. Women’s fashion, especially in the 50s and early 60s, restricted women through tight corseting and defined waists (Reddy). Men traditionally were afforded comfort and utility that women were not allowed. Peggy Moffit, muse and friend to Gernreich over his long career, said of his caftans:

“To me the whole point of a caftan is freedom… The advocates of couture dressmaking (almost always men) have said to me for years that such and such a dress is wonderful because it is so stiff and constructed that it can stand up on the floor all by itself. My reply has always been, let it. It doesn’t need me to hold it up, and I don’t need the torture it will give me.” (154)

To Gernreich, the notion of comfort seemed to be a basic human right that he sought to extend to all genders and people through his unisex designs such as his leotards and caftans from his 1970 collection. Gernreich did not consider fashion frivolous and time and time again his designs were a commentary on larger societal issues regarding gender, visibility, and inclusivity.

Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Caftan, 1970. patterned silk. Los Angeles: Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising Museum, G85.331.17. Bequest of the Rudi Gernreich Estate. Source: FIDM Museum

About the DESIGNER

R

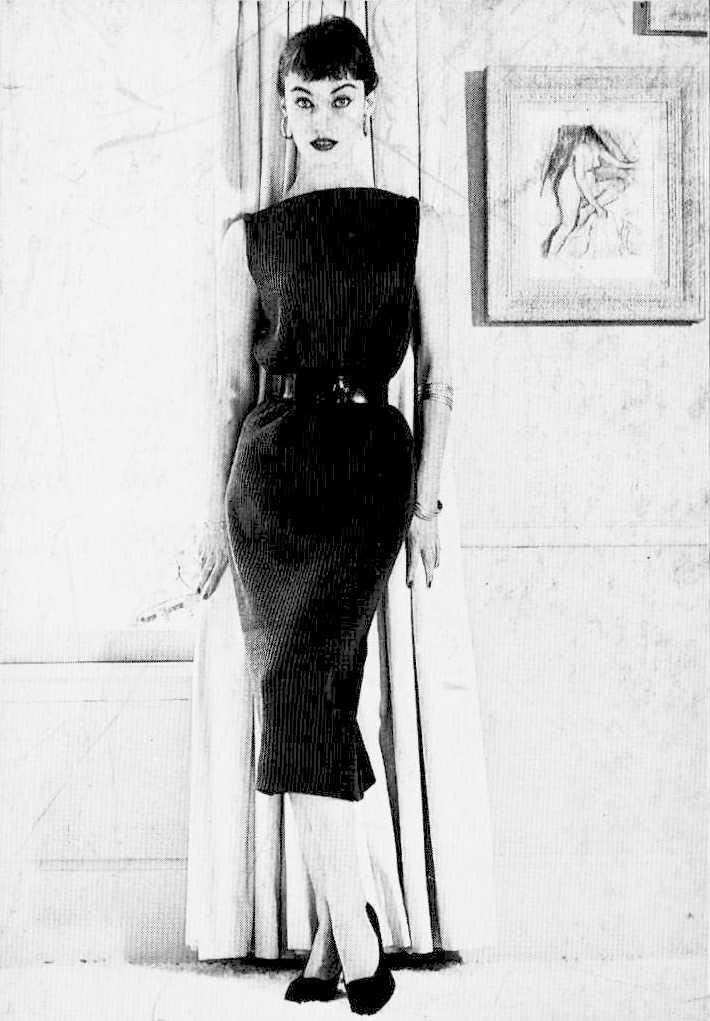

udi Gernreich (Fig. 4) was born in 1922 in Vienna, Austria, migrating to the United States with his family in 1938 following increasing discrimination against Jewish citizens in Austria and across Europe leading up to WWII (Joseph 4). Through the 1940s he developed an interest in dance and found his way into the Lester Horton company, an organization that informed the way he thought about movement, sartorial freedom, and restrictions of clothing, particularly in womenswear (Joseph 6). The mid-1940s saw Gernreich utilizing his fashion skills to create dance costumes (Feldere). Soon, the designer shifted towards the fashion industry and worked creating Dior knockoffs as well as at several other companies including Walter Bass, Harmon Knitwear, and Westwood Knitting Mills (Joseph 18-22).

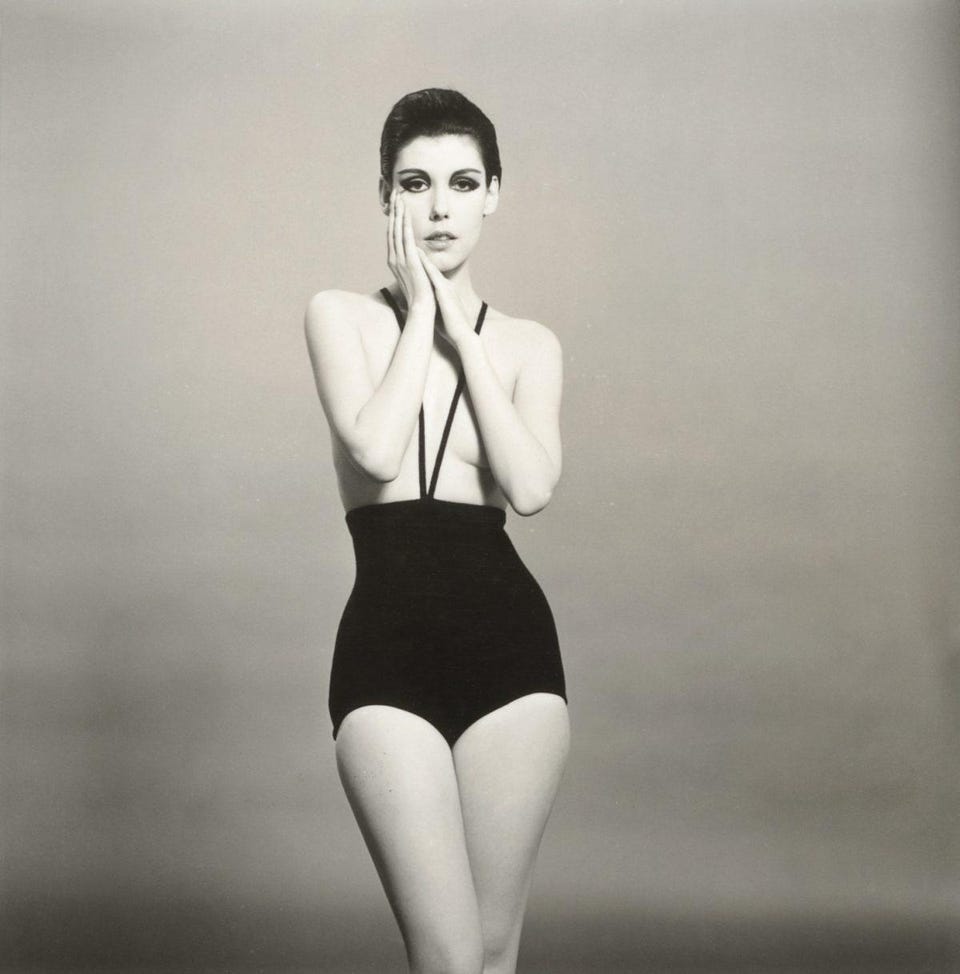

Even in the earliest part of his career, Gernreich was dedicated to freeing women’s bodies from their typical restrictions. In March of 1952, he created a prototype for the first bra-free swimsuit; in 1953, he was featured in a magazine for the first time for his knitted tube dress (Fig. 5)(Moffit 15). In 1960, the designer ended his 8-year collaboration with both Bass and Westwood Knitting Mills in favor of founding his own company, Rudi Gernreich Incorporated (Moffit,17). Gernreich reached new levels of fame with his monokini, a topless bathing suit, in 1964 (Archer 45). The piece was most famously modeled by Moffit who became synonymous with the breast-baring design (Fig. 6). Nicole Archer notes of the tumultuous disapproval from traditionalists in all spheres following the release of the design that:

Fig. 4 - William Claxton (American, 1927-2008). Photograph of Rudi Gernreich, 1964. Source: Vanity Fair

Fig. 5 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Tube dress, 1953. Knitted dress. Source: The Rudi Gernreich Book

“In concert with one another, these dour responses to a relatively novel fashion statement made it absolutely clear that most people thought there needed to be limits placed on the liberation of women and their bodies, and that Gernreich’s fashions represented a dangerous effort to move past traditional gender confines.” (44)

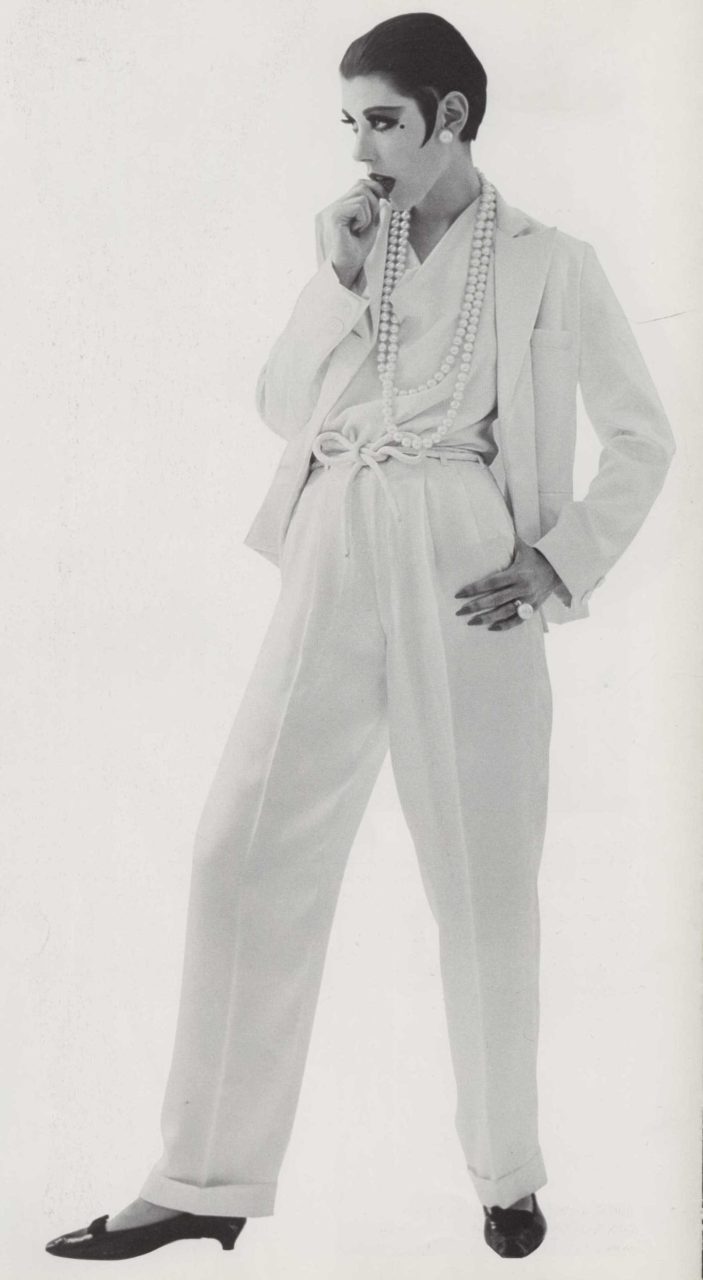

Designs such as the monokini and Gernreich’s later pubikini gave critics of his work the notion that he was simply creating ‘shocking’ fashions for the purpose of publicity but in reality, politics were essential to the work of the designer. The monokini, specifically, was a representation of Gernreich’s support for the fight for women’s sexual liberation in the 1960s and desire to fight against the notion that women were merely sex objects devoid of identity. Gernreich’s ‘Marlene Dietrich’ white pantsuit from the same year that he attempted to premiere at the Coty Award presentation was shut down by members of the jury who noted that model Peggy Moffit ‘looked like a lesbian’ (Moffit 18) (Fig. 7). As far back as 1950, Gernreich was involved in politics as a founding member of the Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organizations in the United States (Fig. 8) (Joseph 12). Art director Jacques Faure noted of Gernreich’s politically charged designs, “Gernreich wasn’t a fashion designer. He was a fashion activist. He was more interested in social statements than in pretty things to wear” (Joseph 43).

Fig. 6 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Monokini, 1964. Photo by William Claxton. Source: Forbes

Fig. 8 - Photographer unknown. The Mattachine Society, 1950. Photograph. San Francisco: San Francisco Public Library. Source: Q Voice News

Fig. 7 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Marlene Dietrich suit, 1964. Source: The Rudi Gernreich Book

About the Context

T

he 1970 caftan was created as a part of Gernreich’s involvement in Expo ‘70, Japan’s world exposition held in Osaka in 1970 in which 77 countries participated and over 64 million people attended (Fig. 9). The theme of the exhibition that year was “Progress and Harmony for Mankind” with four sub-pillars including “designing a better everyday life,” which was the category under which clothing fell (Tower of the Sun Museum). To Gernreich, fashion in the future would no longer feature the strict gender divisions it had been prison to for centuries. In 1971 Gernreich stated, “In the new environment of the future, people will accept their bodies. Clothes will be utilitarian, organic, and minimal. It will free us to think of more important things” (Rozzo).

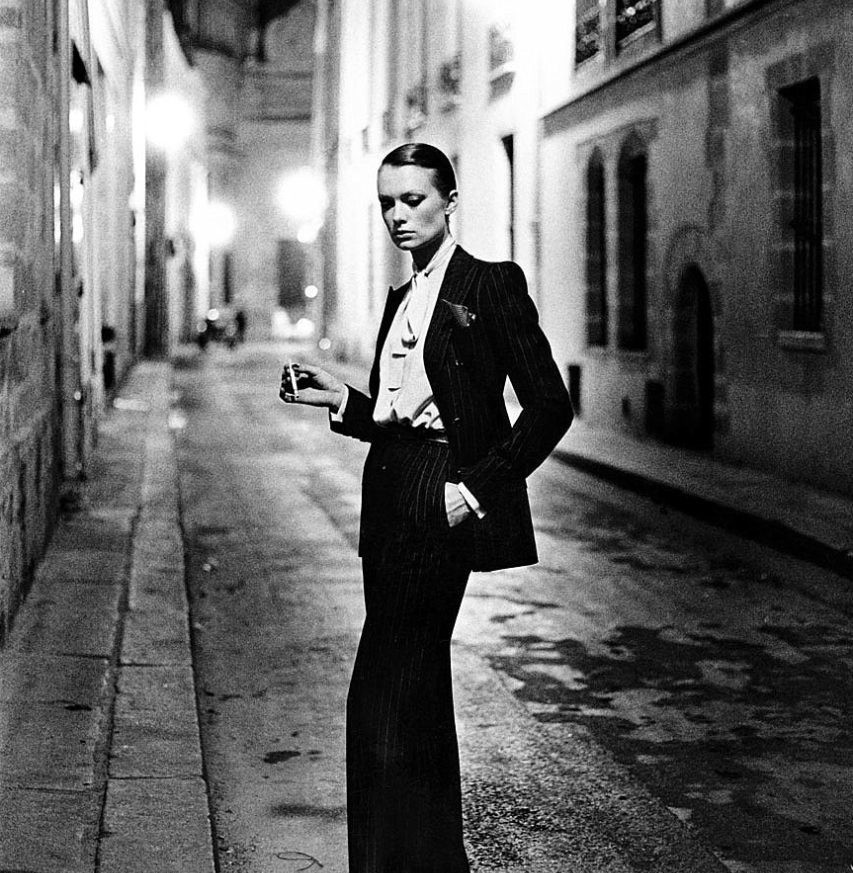

Gender neutrality in dress is not a new concept, indeed the modern notion of gendered clothing is a relatively recent one found in the West. The global trend of gendered fashion over the past centuries is noted by Marissa Fessenden as “colonialism dressing the world in the West’s image. By the 1960s and 1970s, though, designers began to question the limits of what could be considered gendered fashion. Movements of the 1960s including the Youthquake and revolutionary designers like Mary Quant formulated the mini-skirt and helped to push the boundaries of the feminine fashions that dominated during the 50s (Reddy). The decade of the 60s also saw an influx of inspiration for menswear in women’s clothing such as the 1966 Le Smoking suit from designer Yves Saint Laurent (Fig. 10) (Reddy). On the other hand, the so-called ‘Peacock Revolution’ of menswear started back as early as the 1950s and encouraged men to wear brighter colors and bolder prints (Fig. 11), moving away from the strict notions of masculinity also enforced during the post-war years (Reddy).

Fig. 9 - Photographer unknown. Staff of the Japan World Exposition Association, 1970. Photograph. Suita: Tower of the Sun Museum. Source: Expo '70 in Osaka

Fig. 10 - Helmet Newton (German-Australian, 1920-2004). YSL Smoking Suit, 1975. Paris: Grand Palais. Source: The Code

Fig. 11 - Liberty co., John Michael, Hung on You, Mr. Fish, and Hayward. Assortment of Men's Ties, 1960s. Printed silk and silk/satin lined with satin or wool. London: Victoria & Albert Museum. Source: V&A

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown. Kaftan, late 19th-early 20th century. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.41.86.8. Gift of George R. Dyer, 1941. Source: The Met

Fig. 13 - Cristóbal Balenciaga (Spanish, 1895-1972). Evening Wrap, 1951. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1973.21.3. Source: The Met

The caftan, also spelled as kaftan (Fig. 12), originated with an ancient Persian long, loose-fitting tunic made in a style similar to the t-cut tunic (Hill 166). It was unisex and worn by both men and women. In Ottoman Turkey, the garment was worn by high-ranking officials meaning it was a venerated form of dress worn by some of the wealthiest members of society (Hizkiyev). Still, there were often slight differences reflecting the gender binary within fashion such as the different pattersn, shortened hems and wider sleeves in the kaftan (Condra 9). The use of the kaftan in Western dress began as early as the 19th century as part of the general ‘orientalist’ trends that continued through the Edwardian era. Laura Helms notes that by the 1950s and 1960s, French couturiers who were considered to be at the forefront of the decade’s fashions, including both Christian Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga (Fig. 13), had begun to include styles quite similar to the kaftan within their collections.

“The kaftan lent itself well to the fashions of the next decade; providing a simple silhouette that could be beaded, heavily patterned, or sleekly minimal (as seen in the designs of Halston in the 1970s). Women entertaining at home wore the “kaftan dress,” while at the same time more traditional silhouettes were being brought into the United States and Europe by young people who had traveled the nascent “Hippie trail” from North Africa to Afghanistan. The popularity in America of the kaftan—from high end to mass market and cheap imports—stemmed from its association with exoticism as well as the easy-to-wear comfort of these pieces.”

Fig. 14 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Tom Boome and Renée Holt in 'The Unisex Collection', 1970. Photo by Patricia Faure. Source: The Historialist

The style of the caftan, therefore, had entered the minds of American and French designers over the past few decades and was adopted by Gernreich as the perfect garment to represent his beliefs on gender-neutral fashions. As compared to the work of earlier designers, Gernreich’s caftan and 1970 collection were unique because it was one of the first times a well-known couturier had designed an entire collection that was intended to be worn by all people regardless of their gender. Small changes in women’s and menswear such as the introduction of pantsuits or colors were nothing compared to the systemic change to the fashion system that Gernreich aimed for with his designs. Women’s pantsuits, for example, were often fitted to curve around the wearer’s bodies despite the same not being true of the male originals. Models Renée Holt and Tom Boome were famously photographed in Gernreich’s 1970 unisex collection wearing pieces such as wool-knit jumpsuits, miniskirts, matching two-piece sets, and the iconic caftans (Figs. 14-16). Of the collection and the future of fashion, Gernreich stated,

“Clothing will not be identified as either male or female…women and men will wear skirts interchangeably… the aesthetics of fashion are going to involve the body itself.” (Moffit 182)

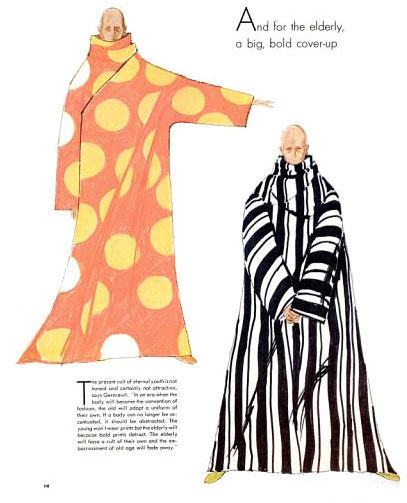

Central to Gernreich’s notion of blurring gender lines was to do so with loose and movement-based garments that were covered in vibrant patterns to further obscure the body of the wearer underneath particularly for older people, who might be less comfortable in the body hugging unitards he also designed. The multi-color circles and graphic lettering that make up the caftan (Fig. 16) take a clear influence from the op-art style that had permeated the visual sphere. Beginning as early as the 60s, around the same time Gernreich was gaining prominence, Op-art painters like Bridget Riley (Fig. 17) focused on geometric forms to create optical illusions (Tate). Various caftans and dresses modeled by Peggy Moffit represent Gernreich’s dedication to bold prints in his designs. Of his continual use of patterning throughout his career Brigitte Felderer writes,

“Gernreich used patterns—bold animal skins or graphic decorations—in clothing, accessories, and even underwear. The body became, in the Total Look, an abstract, aesthetic element, and clothing became a conscious field of aesthetic experimentation, like architecture or furniture design.”

Fig. 15 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Tom Boome and Renée Holt in 'The Unisex Collection', 1970. Photo by Patricia Faure. Source: The Rudi Gernreich Book

Fig. 16 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Sketches of 'The Unisex Collection' from LIFE Magazine, 1970. Source: The Historialist

Fig. 17 - Bridget Riley (English, b. 1934). Untitled [Fragment 5/8], 1965. Screenprint on perspex. London: Tate Museum, P07108. Source: Tate

Gernreich was not simply creating clothing to be worn without intention, but rather he was using his art to represent his beliefs on liberation, the queer community, and removing society’s commitment to an unwavering gender binary. Although the work of other 60s designers took influence from either menswear or womenswear in their gendered collections, Gernreich went one step further. Marissa Fessenden notes that, “In the past century there have been plenty of rebellions against the gender division in fashion, but they have often been one-sided: Fashion has often put women models in tailored suits and called it androgynous”. Gernreich paved the way for later gender-less collections and fully unisex brands. His 1970 collection and the subsequent photoshoot with two gender-ambiguous models were revolutionary for his time and proved how much of an innovative thinker and designer he was.

Its Afterlife

In recent years Gernreich’s work has been reevaluated by scholars for his contributions to the queer community and representations of gender-neutrality as early as the 1970s. In the 2021 exhibition “Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich” held at the Phoenix Art Museum, Gernreich’s long design career was celebrated for his continuous efforts towards using his clothing to promote equality, women’s liberation, and freedom for all gender expressions and identities (Fig. 18). Despite critiques and attacks from conservative critics, Gernreich continued to create exceptionally progressive works until his death in 1985 that still resonate with viewers today. With the divide between men’s and women’s fashion still so deep and the efforts to push for more unisex fashions on the runway only happening most recently, Gernreich appears as a true trailblazer who commented on politics through ravishing and playful garments.

Fig. 18 - Rudi Gernreich (Austrian, 1922-1985). Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich Exhibition, 2021. Phoenix: Phoenix Art Museum. Source: Art and Cake

Fig. 19 - Harris Reed (British-American, b. 1996). Reed and Trey Trey for Grazia, Feb 2022. Source: Harris Reed

Fig. 20 - Marc Jacobs (American, b. 1963). Heaven by Marc Jacobs, 2020. Source: Office Mag

Gernreich’s influence is felt in the work of contemporary designers pushing for greater gender neutrality in the binary fashion industry. Designers such as Telfar Clemens have been making gender-neutral designs since as early as 2005 (Archer). The brand’s tagline itself highlights the fact that their clothing isn’t intended to be worn by any one gender noting that it’s “not for you— for everyone” (Archer). Additionally, the half-British half-American designer Harris Reed strives for gender fluidity and what they describe as ‘romanticism gone non-binary’ in their works (Fig. 19). Such an inclusive take on fashion has allowed Reed to design for some of the biggest names in the entertainment industry even while still attending school at Central Saint Martins (Archer). Luxury fashion houses have recently turned towards gender-neutral collections such as Marc Jacobs’s 2020 polysexual collection referred to as ‘Heaven’ (Fig. 20). The Instagram for the brand noted the collection was inspired by various historical queer figures including Greg Araki as well as:

‘girls who are boys and boys who are girls, those who are neither, negative space’ (Ong).

It is one thing for smaller, underground businesses to be creating gender-neutral fashions, but it is wholly another when larger contemporary designers and brands with so much sway in setting global trends have begun to move beyond the gender binary. Such a change within the industry as more and more creators begin to hop on the ‘trend’ of designing unisex collections owes its origin in part to Gernreich who fought tirelessly for his clothing to be thought of as political and important beyond just how it looked on the runway.

References:

- Archer, Harry. “The 5 Best Designers Creating Gender-Neutral Clothing.” Editorialist. YX. December 14, 2020. https://editorialist.com/fashion/gender-neutral-clothing/.

- Archer, Nicole. “Rudi Gernreich and the Art of Bad Timing.” Textile 14, n. 1 (2016): 36. https://www.academia.edu/29510338/Rudi_Gernreich_and_the_Art_of_Bad_Timing.

- Castaldo Lundén, Elizabeth. “Fearless Fashion: Rudi Gernreich.” Fashion Theory 24, n. 5 (2019): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704x.2019.1664527.

- Condra, Jill. Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing Around the World. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2013. https://search-ebscohost-com.libproxy.fitsuny.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=658629&site=ehost-live

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950

- Felderer, Brigitte. “Gernreich, Rudi.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed July 6, 2022. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474264716.0007951.

- Fessenden, Marissa. “Gender-Neutral Clothes Are Trendy, but Not New — Humans Dressed Similarly for Centuries.” Smithsonian. April 29, 2015. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/gender-neutral-clothes-arent-new-humans-dressed-similarly-centuries-180955109/.

- FIDM Museum. “Rudi Gernreich Garments Featured in a Queer History of Fashion.” Fashion Institute of Design and Merchandising. September 21, 2013. https://fidmmuseum.org/2013/09/rudi-gernreich-garments-featured-in-a-queer-history-of-fashion.html.

- Helms, Laura. “How the Kaftan Went Global.” Vogue Arabia. March 2, 2018. https://en.vogue.me/fashion/how-the-kaftan-went-global/.

- Hizkiyev, Ofir. “Kaftan | Fashion History Timeline.” March 19, 2022. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/kaftan/.

- Joseph, Alexander Low. “Fashion, Politics, and the Career of Rudi Gernreich.” Fashion Institute of Technology, State University of New York, 2013. https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.fitsuny.edu/dissertations-theses/fashion-politics-career-rudi-gernreich/docview/1685033151/se-2?accountid=27253.

- Moffitt, Peggy, and Marylou Luther. The Rudi Gernreich Book. Koln: Taschen, 1991. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/925246106

- Ong, Kimberly. “Fashioning the Future: Marc Jacobs Has Launched a Polysexual Collection | L’Officiel Singapore.” L’Officiel. September 10, 2020. https://www.lofficielsingapore.com/fashion/is-gender-neutral-fashion-the-future-here-are-the-brands-to-know-now.

- Reddy, Karina. “1960-1969| Fashion History Timeline.” July 23, 2019. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1960-1969/.

- ———. “1970-1979 | Fashion History Timeline.” October 3, 2019. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1970-1979/.

- Rozzo, Mark. “How Rudi Gernreich, Fashion’s Utopian Prophet (and Inventor of the Thong), Saw the Future.” Vanity Fair. May 3, 2019. https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2019/05/rudi-gernreich-thongs-and-fashion.

- Tate. “Op Art – Art Term | Tate.” Tate Museum. 2017. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/o/op-art.

- Tower of the Sun Museum. n.d. “About Expo ’70 in Osaka.” https://taiyounotou-expo70.jp/en/about/expo70/.

![Untitled [Fragment 5/8] Untitled [Fragment 5/8]](https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/G-17.jpeg)