Jean-Marc Nattier, an acclaimed 18th-century portraitist, was known for his mythological style, painting women in imagined costume that was only loosely based on fashionable trends, as is true in his 1750/60 Portrait of a Woman.

About the Portrait

Jean-Marc Nattier (1685-1766) was one of the greatest French portrait painters of the 18th century. Art historian Cathrin Klingsöhr-Leroy describes Nattier’s style of painting as “allegorical and mythologizing” (2). He was known for painting beautiful and goddess-like women and his contemporaries cherished his work (Duveen). He had incredible success, especially towards the end of his career when he painted this Portrait of a Young Woman. Nattier is said to have described his own skills and successes to Casanova by remarking:

“The gods have granted me a kind of magic–the power to transfer from my mind to my brush the divine charm of beauty,–a charm none can define, since none can tell wherein it lies, and yet one which all recognize and admire.” (Brown 28)

Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685 – 1766). Portrait of a Young Woman, 1750/1760. Oil on canvas; 80.9 x 64.5 cm (31 7/8 x 25 3/8 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1960.6.28. Timken Collection. Source: NGA

About the Fashion

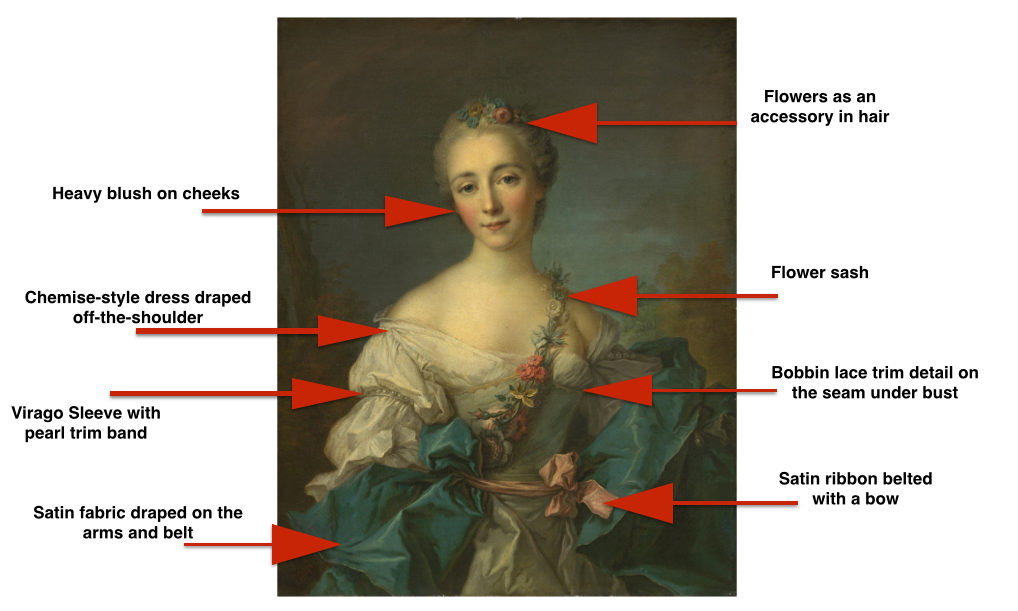

The unknown sitter in Jean-Marc Nattier’s Portrait of a Young Woman sits gazing into the viewer’s eyes. She is typical of Nattier’s style of painting women, but not dressed in the style of her time. She is instead painted with deconstructed elements of the 18th-century style of dress. Her off-the-shoulder draped chemise-style dress exposes her décolletage. Such exposure was not unusual, 18th-century women would wear their dresses off-the-shoulder or fitted with a very open neckline. On her dress, she has sleeves cinched with pearls, which could also be seen in fashionable 18th-century womenswear. Under her bust, there is a delicate trim of bobbin lace (this lace is created using multiple bobbins of thread). Nattier painted her cheeks rose with blush, which was a popular cosmetic style during the Rococo period (Hill). The sitter is decorated with flowers along her sash and in her hair. At her waist, there is a a pink satin ribbon secured with a bow.

Jean-Marc Nattier’s portrait of the Princesse de Rohan (Fig. 1) shares the same loosely neoclassical dress which he painted in Portrait of Young Woman. Both sitters wear a draped chemise dress with a shawls of blue satin fabric draped around their bodies. The Princesse de Rohan is less embellished than the sitter in Portrait of a Young Woman as she lacks both flowers and pearls, but they both wear clothing that was not considered the fashion of the time.

Figure 2, Nattier’s portrait of the Marquise d’Antin, shows a more conventionally fitted bodice (though the same floral sash and hair adornments), suggesting that our subject chose to be depicted in this looser style.

Figure 3 goes so far as to cast its subject, Charlotte Louise de Rohan, as a specific goddess, in this case Hebe. Figure 4 depicts Mme Henriette de France as a Vestal Virgin. Our subject shares a similar mythological style as she wears the same chemise dress, draped satin fabric, and flowers in her hair, but is seemingly not associated with a specific goddess.

Nattier’s Portrait of a Woman and her Dog (Fig. 5) has a very similar style to Portrait of a Young Woman. The sitter is dressed in a heavily decorated chemise dress with pearl-adorned sleeves, as well as an ermine-lined shawl.

Fig. 1 - Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685 - 1766). Princesse de Rohan, 18th Century. Oil on canvas; 60.325 x 50.4825 cm (23 3/4 x 19 7/8 in). Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2018.298. Bequest of Justine Kirk in memory of her uncle, H. Medill Sarkisian. Source: Denver Art Museum

Fig. 2 - Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685-1766). Portrait of the Marquise d'Antin, 1738. Oil on canvas; 118 x 97 cm (46.4567 x 38.189 in). Paris: Musée Jacquemart-Andre. Source: Musée Jacquemart-Andre

Fig. 3 - Jean Marc Nattier (French, 1685-1766). Portrait of Charlotte Louise de Rohan as Hebe, 18th Century. Oil on canvas; 46 x 37.5 cm (18.1 x 14.8 in). Private Collection. Source: Artnet

Fig. 4 - Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685-1766). Madame Henriette de France as a Vestal Virgin, 1749. Oil on canvas; 180.3 × 133.4 cm (71 × 52 1/2 in). Detroit: Detroit Institute of Arts, 43.417. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Edgar B. Whitcomb. Source: Detroit Institute of Arts

Fig. 5 - Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685-1766). Portrait of a Woman and her Dog, 1750. Oil on canvas; 101.5 x 80.5 cm (39 15/16 x 31 11/16 in). Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 37.895. Acquired by Henry Walters, 1905. Source: The Walters Art Museum

Fig. 6 - Ulrica Fredrica Pasch (Swedish, 1735-1796). Kristina Sofia Silfversköld, gift Drufva (1726-1779), 18th century. Oil on canvas; 76 x 63 cm. Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, NMGrh 1892. Source: Nationalmuseum

Fig. 7 - Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685 -1766). Madame de La Porte, 1754. Oil on canvas; 80.8 x 64.1 cm (31.81102 x 25.23622 in). Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 119.1992. Gift of William Bowmore OBE 1992. Source: Art Gallery of New South Wales

The Setting & Context

In An Exhibition of Masterpieces by French Painters of the XVIII Century: On Behalf of the Funds of the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution (1906), the Duveen Brothers explain that Nattier was known for painting:

“Princesses, high-born ladies, favorites, etc. generally represented as mythological characters, or in allegorical disguises.” (55)

The viewer can assume that the sitter is of high nobility because of the type of clients Nattier had during his successful career. Her mythological costume disguises her identity and makes difficult exactly dating this piece, which is estimated to have been painted between 1750 and 1760.

Contrary to what the sitter is wearing in Nattier’s portrait, women of the 18th century were known to wear elaborate dresses with trains, lace, silk brocades, and heavily decorated petticoats and stomachers. During this time, women would accessorize their looks with lots of ribbons, especially an échelle, or rows of ribbon down the stomacher (Fig. 6). Ulrica Pasch’s portrait of Kristina Sofia Silfversköld (Fig. 6) depicts a fashionable dress of the day with its échelle of ribbons on the stomacher, lace engageantes (sleeves) and tightly fitted bodice.

Nattier’s portrait of Madame de La Porte (Fig. 7) depicts the sitter in more traditional Rococo costume, with an elaborate gold silk brocade textile and prominent bow on the bodice. Yet they share the same flowers in their hair and blush on their cheeks. Both women are unmistakably 18th century in their aesthetic and sensibility, even if you could only encounter one of them in real life.

References:

- Brown, Philip, ed. “The Art of Nattier.” In Masters in Art: A Series of Illustrated Monographs. Vol. 3. Boston: Bates and Guild Company, 1902. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1587836.

- Duveen Brothers. An Exhibition of Masterpieces by French Painters of the XVIII Century: On Behalf of the Funds of the Artists’ General Benevolent Institution. London: Chiswick Press, 1906. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/272554660.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. An abridged history of world costume & fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/144219806

- “Jean-Marc Nattier.” Accessed November 14, 2018. https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1746.html#biography.

- Klingsöhr-Leroy, Cathrin. 2003 “Nattier family.” Grove Art Online. 18 Nov. 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000061447.

- North, Susan. 18th-century Fashion in Detail. London: Thames and Hudson, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1027724031

- Ruby, Jennifer. Costume in Context: The Eighteenth Century. London: Batsford, 1989. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1017141950