OVERVIEW

The 1490s was an influential decade that set the groundwork for the following years to come in terms of predominant trends and silhouette. At the same time, regional influence held strong both in Italy and Spain.

The course that fashion would take for the first third of the sixteenth century was laid in the 1490s, which was an exciting and turbulent decade. Multiple trends converged in Italy, where there were distinct regional styles influenced by the dress of other nations. Spanish influence predominated in Milan, whereas German and Turkish influence was seen in Venice. The invasion of Italy by French troops in 1494 helped to blur distinctions between northern and southern Europe, and the voyages of exploration opened up the entire world for sea-going trade.

Womenswear

Women’s dress continued to be based upon the chemise, a long-sleeved undergarment of undyed linen (Boucher 445). An allegory of love by a follower of Botticelli (Fig. 1) shows us what the chemise looked like in this decade, its fullness gathered by means of drawstrings at the neckline, high waistline, and upper sleeve. Over it went the dress, called the gamurra in Italy (Herald 217). The gamurra was cut to fit tightly, with the bodice fronts deliberately too narrow to meet in the front, and sleeves too narrow to encircle the arm. Sleeves were also modular pieces that could be made of contrasting fabric and were typically only semi-attached at the shoulder. This style of split bodices and sleeves had originated in Spain and taken hold in Italy beginning in the 1470s (Frick 158). What is new in the 1490s, as seen in Lorenzo di Credi’s Portrait of a Young Woman (Fig. 2), who may be Caterina Sforza, Countess of Forli and niece of Ludovico il Moro, Duke of Milan, is that the bodice fronts are very far apart, necessitating the use of an inserted triangular stomacher. In this portrait the gamurra is made of blue fabric, either wool or silk, and the stomacher is green. Red was chosen for the laces that hold the bodice and sleeves together, across the gaps where the white chemise is exposed. Another new feature in the 1490s is that laces, which had been primarily utilitarian in the past, become more important as details that focus attention and coordinate an ensemble (Herald 193). The dark red color of these laces matches the belt, which conceals the seam at the waistline where the moderately full skirt of the gamurra is joined to its fitted bodice. The entire garment and the stomacher would be lined in linen to protect the outer fabric and reinforce the tight fit (Herald 210). The slightly high waistline and the hairstyle in this portrait are in the Florentine style.

In the engagement scene from Verona (Fig. 3), we see a higher waistline, creating a silhouette that is like a straight, slender column. The three young women are all wearing outer garments over their dresses. The woman at the far left wears a black gamurra with contrasting golden-colored sleeves that are split in two places to reveal her chemise. The red garment on top is the giornea (Herald 218), a sleeveless cape made of two widths of fabric, one covering the front and the other the back of the body; the giornea can be sewn closed at the sides, as in these examples, or left open. The other young women also wear giorneas layered over their dresses. The woman who is receiving a ring from her future husband wears a creamy white giornea that is slit in the front to reveal the golden skirt of her gamurra underneath. The V-neckline of the giornea, emphasized with a trimming of gold braid, allows us to see the front of her gamurra, or possibly a stomacher, made of red silk velvet embroidered with gold crosses. The gamurra sleeves are also of red velvet. Because the layered garments are made of unpatterned silks that are lighter in weight than brocades, narrow in cut and belted at the high waistline, the desired straight and slender silhouette is maintained. The bride-to-be wears a small black cap that comes to a point over her forehead, where a brooch (called a fermaglio, Herald 216) has been placed, and her long golden hair flows freely down her back unveiled, traditionally the privilege of unmarried women (Van Buren and Wieck 180). The other women wear veils of very fine, transparent linen or silk, a style that originated in Bologna (Herald 195).

The simplicity seen in Verona, which in the 1490s was part of the Republic of Venice, contrasts with the fashions of the court of Milan. Ambrogio da Predis’s profile portait of Bianca Maria Sforza, sister of Duke Ludovico il Moro (Fig. 4) illustrates a gamurra of voided silk velvet with the entire ground of the weave brocaded in gold; this textile qualifies as the “cloth-of-gold” that was the ultimate Renaissance luxury (Monnas 323). Such a quantity of metallic fiber would have made the dress very stiff. The fitted bodice has a square neckline and a waistline at the natural level, much lower than that seen in Verona. The sleeves are in a style considered to be particular to Milan, constructed in narrow vertical strips held together with laces. In fact this type of sleeve originated in Spain, as seen in a Catalan painting from the 1470s (Fig. 5); what was added in Milan were the stringhe (Herald 220), the long ends of the laces that were left to hang down the arm, sometimes tied in bows. Another important aspect of Milanese fashion that was adapted from Spain is the hairstyle, which in Spain was called the cofia tranzado (Bernis 52). The hair was center-parted and drawn back into a long coil, which in Milan was called the coazzone (Herald 202). The coazzone could be entirely encased in fabric and/or covered by criss-crossing ribbons, as seen in this portrait; a fine linen or silk hairnet (called the rete, Herald 202), usually decorated with embroidery, was placed at the back of the head. The finishing touch was a headband called a lenza, usually a fine black silk cord tied around the crown of the head, sometimes with a jewel at the center of the forehead (Herald 222).

Bianca Maria Sforza wears a large fermaglio brooch, incorporating the Sforza motto “merito et tempore” (with merit and time) with pearls and other gemstones, at the side of her gold and pearl-embroidered rete. Her coazzone’s interlaced ribbons are studded with pearls. She wears more pearls and other jewels in the forms of a necklace and a belt. However great the debt to Spain for the original inspiration, by the end of the 1490s these styles, championed by the Duchess of Milan, Beatrice d’Este, were considered decidedly Milanese (Herald 202). What struck visitors to the court were the many details that contributed to the richness of women’s attire, a quality that was not to the taste of all observers. The humanist Baldassare Castiglione, who advocated dressing simply and soberly, derided Milanese style as overly “loud and showy” (quoted by Herald 203). He might not have approved of Venetian fashion, either.

Fig. 1 - Anonymous Florentine painter; follower of Sandro Botticelli (Italian, c.1445-1510). An Allegory, ca. 1500. Tempera and oil on wood; 92.1 x 172.7 cm,. London: National Gallery of Art, NG916. Source: NGA

Fig. 2 - Lorenzo di Credi (Italian, 1459-1537). Portrait of a Young Lady or Portrait of Caterina Sforza, ca. 1490. Panel; 75 x 54 cm. Forlì: Pinacoteca Civica. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Michele da Verona (Italian, 1470-1540). The Giving of the Ring, 1495-1500. Berlin: Gemäldegalerie. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Ambrogio da Predis (Italian, 1455-1508). Portrait of Bianca Maria Sforza, ca. 1493. Oil on poplar panel; 51 x 32.5 cm. Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1942.9.53. Widener Collection. Source: NGA

Fig. 5 - Pedro Garcia de Benabarre (Spanish, 1445-1485). Detail of Herod's Banquet, ca. 1470. Tempera, stucco reliefs and gold leaf on wood; 197.5 x 125.7 x 6.4 cm. Barcelona: Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, 064060-000. Muntadas collection, purchased 1956. Source: MNAC

Fig. 6 - Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528). A Venetian Woman, 1495. Drawing (feather in gray and black, brush in brown); 29 x 17.3 cm. Vienna: Albertina Museum, 3064r. Source: Albertina

Fig. 7 - Gentile Bellini (Italian, 1429-1507). Detail of The Procession of the Reliquary of the True Cross, 1496. Oil on canvas; 373 x 745 cm (10’7 by 14’0 in). Venice: Gallerie dell’Accademia, 567. Source: GdA

Fig. 8 - Jean Hey (Netherlandish (active France), c. 1455-1505). Margaret of Austria, ca. 1490. Oil on oak panel; 32.7 x 23 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.130. Robert Lehman Collection. Source: MMA

Fig. 9 - Master of Antoine Rolin. Detail of Wedding of Jupiter and Juno in Raoul Lefèvre, Receuil des histoires de Troie, ca. 1496. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothéque Nationale de France, BNF MS fr. 25552, fol. 33r. Source: Gallica

After centuries of trade with the East, first with the Byzantine Empire and since 1453 with the Ottoman Empire, and the creation of its own empire of trading posts throughout the Mediterranean, Venice was the most cosmopolitan city in Europe, attracting people from all over the world. By the 1490s Venetian women had distinctive fashions and customs. The German painter Albrecht Dürer captured the silhouette of a Venetian woman in a drawing made during his visit in 1495 (Fig. 6). As in Verona, the waistline is very high, and the various parts of the gamurra can be made of contrasting fabrics. The bodice of the dress, gathered at the low neckline, is made of a plain, unpatterned fabric, whereas the skirt, revealed when the woman lifts the long train of her outer garment, is made of a silk with a bold woven pattern. The sleeves, which are made in segments loosely laced together, allowing much of the chemise to spill through the gaps, appear to be made of another patterned fabric. The outer garment is the Venetian version of the giornea, barely clinging to the shoulder and open down the front. The back view that Dürer has provided shows that the neckline is very low and wide in the back as well as the front, where it is trimmed with braid.

Venetian women wear their hair cut short and curled at the top and sides, with the rest twisted and piled high at the crown, where it is surrounded by a decorative headband. The drawing is particularly valuable because sightings of Venetian women are relatively rare. The city’s customs demanded that respectable women keep to the domestic sphere and when venturing out in public, cover themselves in a black veil, as seen in Gentile Bellini’s The Procession of the Reliquary of the True Cross (Fig. 7), where several figures in the background, shrouded in black, surround a woman in pink whose veil is a transparent gray. She towers over the other women, as she heads into the church of San Marco with a young boy to help her with her train, probably because she wears very high chopines, platform shoes that could reach over fifty centimeters or twenty inches high (Davanzo Poli 86). Chopines came from the Islamic world, and could have reached Venice from the Ottoman Empire or from Islamic Spain (Bernis 73).

In northern Europe at the beginning of the decade, women’s fashion was still very different. The portrait of the ten-year-old Margaret of Austria (Fig. 8) shows her dressed in the French fashion that dominated northern Europe during this decade. The daughter of Maximilan of Austria, Holy Roman Emperor, and his late wife Mary of Burgundy, Margaret was brought up at the French court as the future wife of King Charles VIII (Metropolitan Museum). The most notable feature of French fashion in the 1490s is the stiffness of the torso caused by the corset. Early corsets were under-bodices of linen stiffened with wood (Boucher 446), worn over the chemise. The next layer of clothing, the dress, in this portrait is made of red silk velvet trimmed with ermine, as befitting the sitter’s status. In this decade dresses in northern Europe fit tightly as in Italy but rarely do they have split bodices or sleeves. The low square neckline is filled in with a gorget, which in the past had been of fine linen. In this portrait we see the newer trend of making the gorget of black velvet (Van Buren and Wieck 248). Margaret’s gorget is decorated with gold embroidery forming interlacing “M”s and “C”s for Charles. Her headdress is also worthy of note, for it is in the new style that will continue beyond the end of the 1400s.

By 1490, pointed cone headdresses are definitely in the past, replaced by a headband with an attached hood. This first version of the French hood is constructed in layers, beginning with the templet, a fabric base laid on top of the head (Van Buren and Wieck 318), which is here made of black velvet and decorated with golden scallop shells, symbols of the French chivalric Order of St. Michel, along the edges. The next layer is probably stiffened with heavy linen or wood, and covered with a golden silk. Next comes the frontlet, which continues from earlier decades, as a band of black silk extending from the top of the head to the shoulder, here made of velvet embroidered with gold and ending in an upturned curve. The hood is mounted on the frontlet at the crown of the head and hangs down the back. Margaret of Austria’s hood is made of interlaced gold braid, backed with black velvet so that her hair is completely hidden except for a few inches at the hairline (Van Buren and Wieck 248).

We can see the development of this headdress and of women’s silhouettes later in the decade in a French manuscript depicting a wedding (Fig. 9). Women’s dresses still have square necklines but there are no gorgets, only trimming along the neckline in a contrasting color, that also extends down the center front. As they lift their skirts, we see that they wear underskirts in contrasting colors. The most significant change is in the long flaring sleeves, that recall the bombard sleeves of the early decades of the fifteenth century (Van Buren and Wieck 295). Except for the bride, whose long hair is exposed, the other women wear French hoods that are entirely black. This silhouette, shaped by the corset, with widening sleeves and skirts, paired with the French hood, will remain in fashion in northern Europe for decades to come.

Fashion Icon: Beatrice d’Este (1475-1497), Duchess of Milan

Beatrice d’Este (Fig. 1), Duchess of Milan from 1494 until her death, was easily the hardest-working fashion leader of the 1490s. She was responsible for the Milanese style, and she put great effort into gathering information about fashion elsewhere, urging Milanese ambassadors to send descriptions and drawings home (Herald 201-202). The fact that fashion in Milan was so heavily influenced by Spain had to do with Beatrice’s identity and upbringing. She was the daughter of Duke Ercole I of Ferrara and the Spanish princess Leonora of Aragon, daughter of King Ferdinand I of Naples. When Beatrice was two years old, her mother travelled back to Naples with her children, to attend the wedding of her widowed father. At the conclusion of the festivities, Leonora was persuaded to leave Beatrice behind, to be brought up at the court of Naples (Scott 168). When she was about seven, she was given a brial (Spanish for dress) made of red silk trimmed with ribbons embroidered “in Moorish style” (Scott 168). Having worn Spanish fashion during her formative years, it is not surprising that she brought it to Lombardy when she married Ludovico “il Moro” Sforza in 1491, at the age of sixteen. The wedding was orchestrated by Leonardo da Vinci, who was just one of the artists employed at the brilliant court of Milan in the 1490s (Beamish).

Fig. 1 - Master of the Pala Sforzesca (Italian). Detail of Ludovico il Moro and his Family Kneeling before the Virgin, 1494-5. Tempera and oil on panel; 230 x 165 cm. Milan: Pinacoteca di Brera, 451. Source: Brera

Beatrice was described by one contemporary, writing in Latin, as “novarum vestium inventrix” – an inventor of new clothing (Muralto, quoted by Herald 138). There is evidence that she designed clothing, such as vesti alla turchesca, in the Turkish style, for herself and the ladies of the court (Herald 139). It’s possible that she saw Turkish and Turkish-influenced styles in Venice, when she travelled there in 1494. She and her older sister Isabella d’Este, Duchess of Mantua, were engaged in a sometimes heated competition, judging by their correspondence, for the services of the finest artists, weavers, tailors and embroiderers. For her sister-in-law Bianca Maria’s wedding to the Emperor Maximilian I in 1494, Beatrice wanted to use a design for a gamurra (also known as a camora) by a certain Niccolò da Correggio, who had prepared it for Isabella. She wrote to her sister:

“If you have not yet ordered the execution of this design, I am thinking of having his invention carried out in massive gold, on a camora of purple velvet, to wear on the day of Madonna Bianca’s wedding…” (Herald 141)

Beatrice’s taste was, as Baldassare Castiglione complained, “loud and showy.” Her wardrobe was remarkable not only for its richness, but also for its size. In 1493, an inventory showed that she had accumulated eighty-four garments in the two years since her wedding (Herald 38).

The colorful striped dress Beatrice wears in her donor portrait in the Sforza Altarpiece was probably made by using liste. A lista was a strip of cloth applied to a garment to create a striped pattern (Herald 222). This embroidery technique, still used today in haute couture, was extremely labor-intensive, but it was no doubt necessary to achieve the pattern that Beatrice required, using the heraldic colors of the Visconti, the historical rulers of Milan — black, gold and blue-gray. The heraldic color scheme reinforces her husband Ludovico’s legitimacy as Duke of Milan. The style of the dress, however, reflects Beatrice’s taste for details that add contrast and texture, such as the pink stringhe laces that are tied in successive bows down her sleeves. Her accessories are all in black and white – her long necklace, with more pearls edging the neckline of her dress, and the transparent linen rete hairnet; her coazzone covered with white fabric with criss-crossing black ribbons, and the delicate black lenza tied around her head, echoing the ironwork necklace at her throat. Beatrice d’Este’s passion for fashion was related to her strong personality and zest for life (Beamish). Unfortunately like so many Renaissance women, she died very young, at the age of twenty-one, after giving birth to her third child.

Menswear

Men’s fashion began with the basic underwear, consisting of a shirt and a pair of drawers, both made of undyed linen (Frick 160). The next garments were the doublet (called the farsetto in Italy) and the hose (calze) which were laced together (Herald 211, 216). In the 1490s, these garments were extraordinarily close-fitting, as seen in a painting by Luca Signorelli (Fig. 1). The doublets are made, like the bodices of women’s dresses, of pieces that are deliberately too small to fit together, so that an expanse of shirt is exposed in the front, with the laces straining across the gap. The shirt is seen at the back as well, since the doublet is too short to fully connect with the back of the hose. As in women’s fashion, men’s sleeves can be made of contrasting materials and only partly attached to the body of the garment, and the laces that connect the garments, and the various parts of the garments to one another, can become the focus of fashion. These men’s doublets are parti-colored, made of color-blocked parts; the colors chosen sometimes indicated the arms or preferred colors of a certain family or confraternity, or the livery accorded to servants and attendants, or the individual’s taste. A garment or accessory that was parti-colored was said to be adigato or adivisato in Italy (Herald 209, 215). Contemporary observers as well as historians have taken note of the unprecedentedly tight fit of doublet and hose, commenting that men appeared naked even while fully clothed. Jacqueline Herald writes that “never before had young men gone about in such tight doublets and hose, openly wearing them without a tunic, as part of general fashion” (Herald 192). Other fashionable features seen here are the small round caps (berrettas, Herald 210) and the shoulder-length blond hair. The leather belts with attached bags were a Catalan fashion (Herald 205).

Despite the rejection of outer garments by many young men, a variety of them existed in the 1490s. Early in the decade, a formal occasion such as an engagement called for a long coat (as seen in figure 3 in womenswear) that could have a variety of sleeve types. These straight and narrow coats had come into fashion in the previous decade on a wave of general Spanish influence. Some historians refer to them as “gowns” or “robes” (Van Buren and Wieck 232) or use the equally vague Italian vestitos and vestimentos (Herald 230-231), the Spanish mongiles, albornices or ropa (Bernice 36-50), or see a connection to the Ottoman caftan suggested by the Italian words turca and tunica alla turchesca (Herald 230). Historians’ confusion about what to call this and other outer garments mirrors the “confusion of styles” (Herald 195) experienced by contemporaries. The loose, flowing silk coats with contrasting linings, worn by foreign ambassadors from a “pagan” land in Carpaccio’s telling of the legend of Saint Ursula, in the later 1490s (Fig. 2) may be inspired by the close contacts between Venice and the Ottoman court.

In another painting in this cycle (Fig. 3) we see the shorter coat, ending above the knee, that will be more widespread in both Italy and northern Europe. This example is of red silk with black velvet lining that folds back on the shoulder to form lapels; the slit sleeves are wide enough to reveal the tight split sleeves of the young man’s gold silk doublet. This doublet is so narrow in the front that all we see are its laces, and the shirt underneath. The young man is wearing parti-colored hose, with one leg further divided into two different sides. His companion wears only doublet and hose, further evidence that for the young, outer garments were optional. Their blond hair is extremely fashionable in Venice, which is attributed to the presence of many long-haired, blond German merchants in the city (Herald 200). The influence was mutual, however. Albrecht Dürer displays a great deal of Italian style in his self-portrait of 1498 (Fig. 4) after his first trip to Italy, revealing his gold-trimmed shirt all the way to the waist and slinging a cape around one shoulder, alla togata (Herald 57).

In other portraits of men from this decade we see the simplicity and sobriety that the iconoclastic friar Savanarola preached. The young man portrayed by the Venetian painter Marco Basiati (Fig. 5) wears a doublet of darkest brown, almost black, with a high neckline. It was not until the final decades of the century that black finally lost its automatic assocation with mourning in Italy, and was instead appreciated for its elegance as it had long been in northern Europe (Frick 175). Another doublet with a high neckline, in turquoise blue (turquino, a color named for Turkey, Herald 230), accompanied by a green coat is seen in a portrait by Leonardo’s pupil Marco d’Oggiono (Fig. 6). Shoulder-length wavy hair and a coat trimmed with a spotted fur would be very fashionable in the new century that was just a few years away. We see similar coats and hairstyles in a French manuscript (Fig. 7). During the 1490s, men’s fashion in Italy and in northern Europe came closer together.

Fig. 1 - Luca Signorelli (Italian, 1441-1523). Detail of Adoration of the Magi, ca. 1492-96. Oil on panel; 21 x 210 cm. Florence: Galleria degli Uffizi. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, 1465-1526). Scenes from the Life of Saint Ursula: Departure of the Ambassadors from the Court of England, ca. 1495-98. Oil on canvas; 280 x 253 cm. Venice: Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia, 573. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Vittore Carpaccio (Italian, 1465-1526). Scenes from the Life of Saint Ursula: Departure of the Ambassadors from the Court of England, ca. 1495-98. Oil on canvas; 280 x 253 cm. Venice: Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia, 573. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528). Self-Portrait, 1498. Oil on wood panel; 52 x 41 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P002179. Source: MdP

Fig. 5 - Marco Basaiti (Venetian, 1470-1530). Portrait of a Young Man, ca. 1495-1500. Oil on wood; 36.2 x 27.3 cm. London: National Gallery, NG2498. Salting Bequest, 1910. Source: NGA

Fig. 6 - Marco d’Oggiono (Italian, before 1487-1524). Portrait of a Man aged 20, 1494. Oil on walnut panel; 53.3 x 38.1 cm. London: National Gallery of Art, NG1665. Source: NGA

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. Vérard Presents the Book to the King on his Way to a Hunt, Guillaume Tardif, Art de fauconnerie et des chiens, 1492. Manuscript. Paris: Bibliothéque Nationale de France, BNF MS Vélin 1023, fol. a. r.. Source: Gallica

CHILDREN’S WEAR

The children of the 1490s continued to be swaddled as infants and dressed in loose-fitting tunics of linen or wool, layered according to the season, during their earliest childhood. Of the two children represented in the Sforza Altarpiece, the younger (Fig. 1) is probably Massimiliano, the first of Ludovico il Moro and Beatrice d’Este’s two sons, shown in front of his mother. He was born in January 1493 and would have been between one and two years old when the painting was completed. He is shown in an improbable kneeling posture, emerging from a swaddling cocoon in a dark green doublet and a padded cap of golden silk decorated with ribbons studded with pearls. The older boy is probably Ludovico’s son by a mistress (Pinacoteca di Brera). He wears a fashionable silk doublet and a gonnellino, a short, sleeveless over-garment worn by boys and young men (Herald 218). In keeping with the political program of this altarpiece, the gonnellino is made with strips (liste) of cloth in the heraldic colors of the Visconti dynasty. By the age of ten, children of the upper classes were dressed like adults, as seen in figure 3, the portrait of Margaret of Austria.

Fig. 1 - Master of the Pala Sforzesca (Italian). Detail of Ludovico il Moro and his Family Kneeling before the Virgin, 1494-5. Tempera and oil on panel; 230 x 165 cm. Milan: Pinacoteca di Brera, 451. Source: Brera

Fig. 2 - Master of the Pala Sforzesca (Italian). Detail of Ludovico il Moro and his Family Kneeling before the Virgin, 1494-5. Tempera and oil on panel; 230 x 165 cm. Milan: Pinacoteca di Brera, 451. Source: Brera

Fig. 3 - Jean Hey (Netherlandish (active France), c. 1455-1505). Margaret of Austria, ca. 1490. Oil on oak panel; 32.7 x 23 cm. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.1.130. Robert Lehman Collection. Source: MMA

References:

- Anderson, Ruth Matilda. Hispanic Costume 1480-1530. New York: The Hispanic Society, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/801964712

- Beamish, Gordon Marshall. “Beatrice d’Este” Grove Dictionary of Art, Oxford Art Online, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/268889955

- Bernis, Carmen. Trajes y modes en la España de los Reyes Católicos. 2 vols. Madrid: Instituto Diego Velázquez del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1978-1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/906312914

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume in the West. New York: Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50529567

- Davanzo Poli, Doretta. Serenissima: The Arts of Fashion in Venice from the 13th to the 18th Century. New York: The Equitable Gallery, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083135161

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes and Fine Clothing. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins U Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195

- Herald, Jacqueline. Renaissance Dress in Italy, 1400-1500. London: Bell & Hyman, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8095698

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Margaret of Austria, b. 1470.” Catalogue Entry.https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/459072

- Monnas, Lisa. Merchants, Princes and Painters: Silk Fabrics in Italian and Northern Paintings 1300-1550. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/804328725

- Pinacoteca di Brera, “Virgin and Child Enthroned with the Doctors of the Church and the family of Ludovico il Moro (‘Sforza Altarpiece’). https://pinacotecabrera.org/en/collezione-online/opere/virgin-and-child-enthroned/

- Scott, Margaret. Fashion in the Middle Ages. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1078920057

- Van Buren, Anne and Roger S. Wieck. Illuminating Fashion: Dress in the Art of Medieval France and the Netherlands. New York: Pierpont Morgan Library, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/770708873

Historical Context

Wikipedia: 1490-1499

Rulers:

- England

- Henry VII (1485-1509)

- France

- Charles VII (1483-1498)

- Louis XII (1498-1515)

- Spain

- Isabella I (1474-1505)

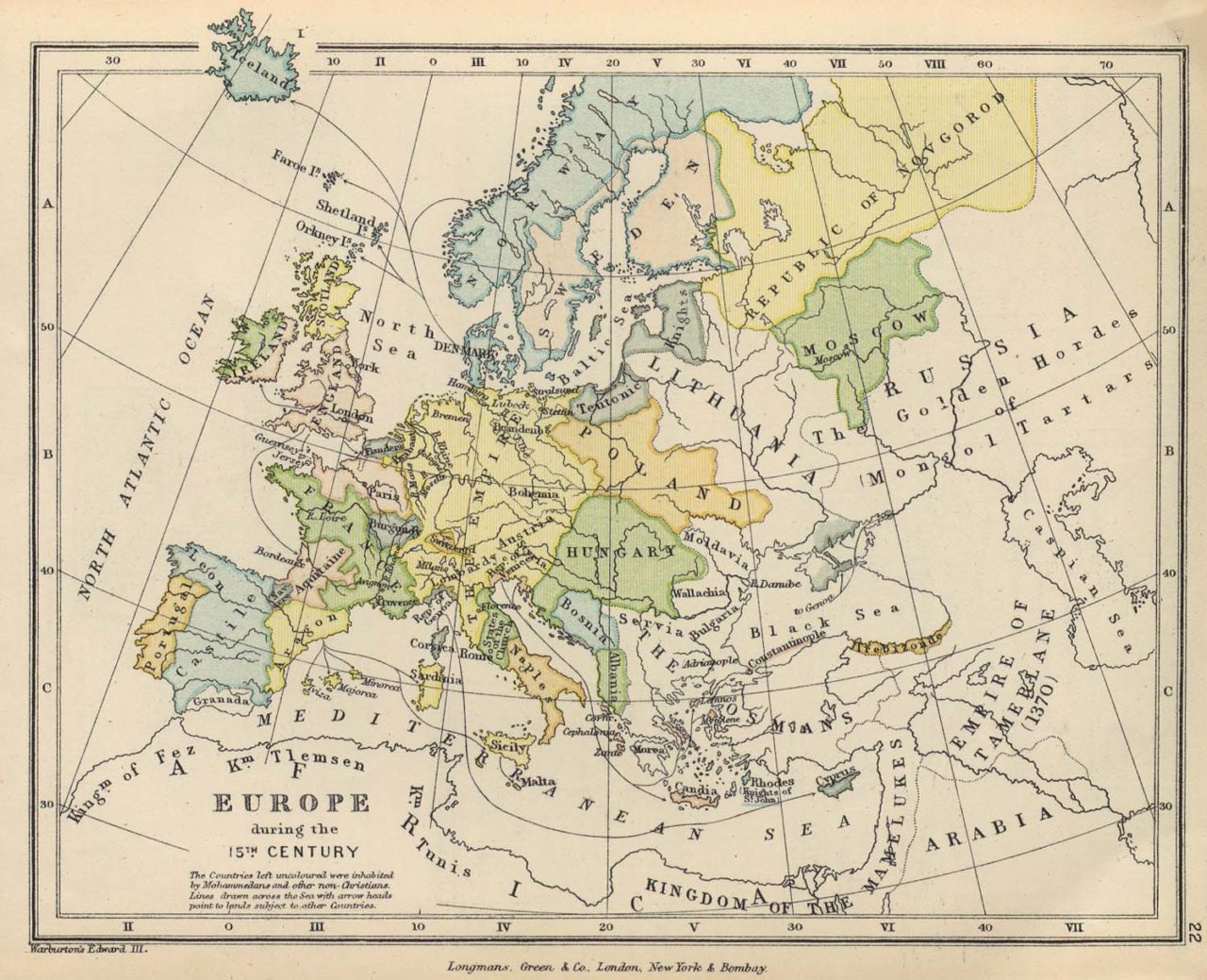

Europe during the 15th Century. Source: University of Texas Libraries

Events:

Timeline Entries

Primary/Period Sources

Resources for Fashion History Research

To discover primary/period sources, explore the categories below.

Have a primary source to suggest? Or a newly digitized periodical/book to announce? Contact us!

Digitized Primary/Period Sources

Secondary Sources

Also see the 15th-century overview page for more research sources… or browse our Zotero library.