By examining fashion modes, economical and societal fluctuations, and urban developments, this essay explores how New York City department stores changed from their initial founding as dry goods stores, developed through the turn of the twentieth century, and emerged in the interwar years.

Introduction

Initially located in the urban environments of Paris and London, department stores are also rooted in mid-nineteenth century America (Kawamura 2010). New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago each had landmark stores by the 1870s. By the early twentieth century, American department stores enjoyed a progression, soon shaping their European prototypes (Edwards 2010). Industrialization and urbanization during the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth centuries established a new middle class, and mass-produced goods were first made widely available to consumers during this time. The spending habits of the burgeoning bourgeois were influenced by new distribution methods offered by department stores. Unlike the tightly linked pre-industrial system of production and consumption, a distinction was created among these activities during the Industrial Revolution, resulting in “change[s] in tastes, preferences, and buying habits” (Kawamura 191-203). Acquiring products extended a shopper’s previous utilitarian needs, since goods could now be purchased for pleasure rather than for pure necessity.

With their European counterparts, New York City department stores such as A.T. Stewart in 1846, Lord and Taylor, initially a dry goods store established in 1826 and a department store by 1853, and Macy’s, a dry goods store founded in 1851 and a department store by 1858, were “harbingers of modern retailing” (Kawamura 191-203). As the twentieth century loomed, two New York City department stores, B. Altman and Siegel-Cooper Dry Goods Store (Gray 1991), joined the Ladies’ Mile, a shopping district between Fourteenth and Twenty-Third Streets along Sixth Avenue and Broadway. Bloomingdale’s (1872) and Bergdorf Goodman (1899), also located in Manhattan, also opened during this time. The habits of the stores’ tailors, milliners, buyers, and customers changed as made-to-measure clothing was offered among ready-to-wear fashions. By examining fashion modes, economical and societal fluctuations, and urban developments, this paper explores how New York City department stores changed from their initial founding, developed through the turn of the twentieth century, and emerged in the interwar years.

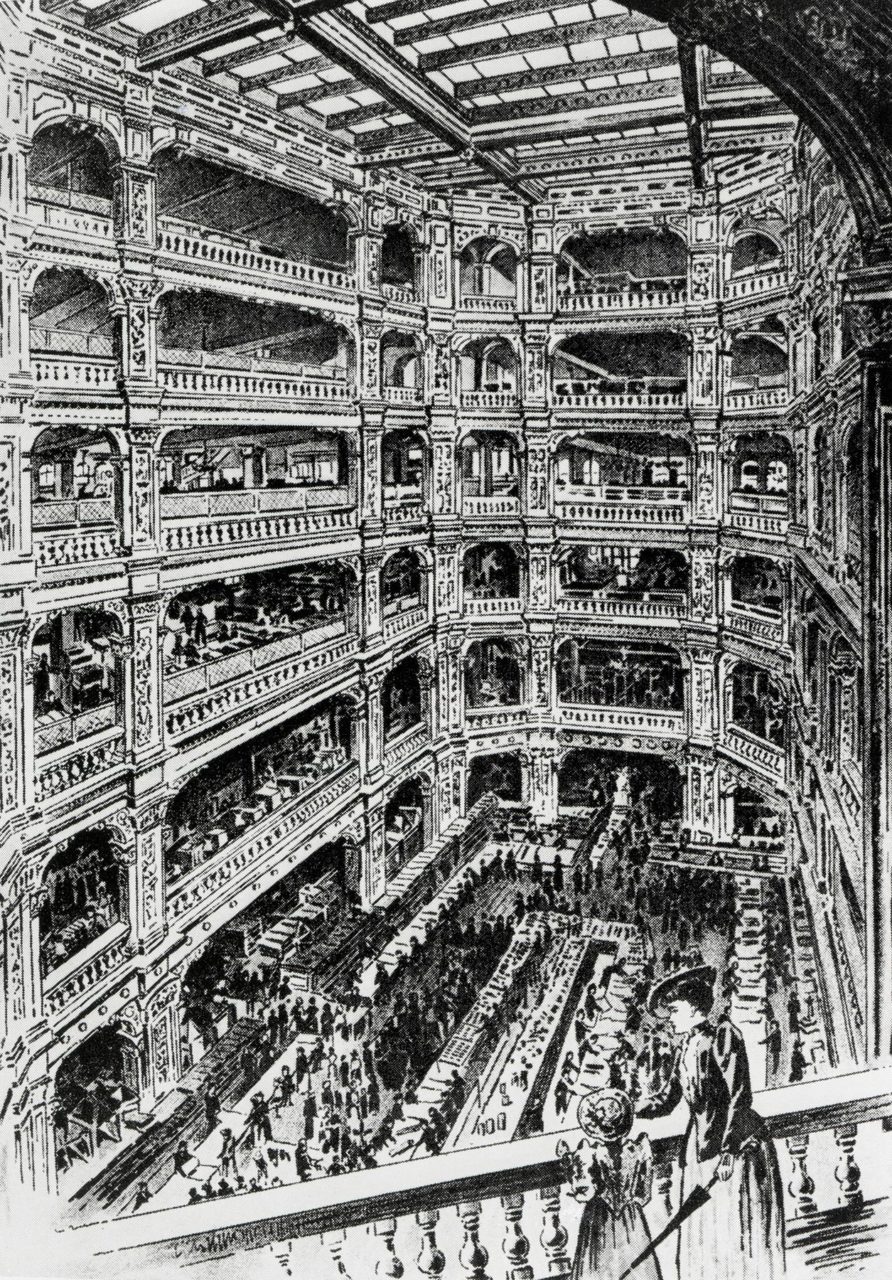

Fig. 1 - Gustave Eiffel; Louis Auguste Boileau. Stairs at Le Bon Marché, 1876. Minneapolis College of Art and Design. Source: Artstor Blog

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Interior of A. T. Stewart’s Astor Place Store, ca. 1880s. Engraving. Bard Graduate Center: Collection of the New-York Historical Society. Source: Bard Graduate Center

DEPARTMENT STORE ORIGINS

Specialty stores selling dry goods soon gave way to a new model of retail—the department store—emerging between 1846 and 1890 (Benson 1986). The term “department store” first appeared in The New York Times in July 1888, although stores of this type already existed for decades. Early Parisian department stores such as Bon Marché, established in 1852, and Printemps, founded in 1865, influenced the global model with their majestic design elements such as wide staircases, balconies, and interior rotundas (Edwards 2010) (Fig. 1). The Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, followed by the New York City Crystal Palace in 1853, helped influence the lavish environment of the department store. Architectural features of glass, iron, light-flooded windows, and high ceilings were hallmarks of early department stores.

A.T. Stewart’s, located at 280 Broadway in downtown Manhattan, was called the “Marble Palace” due to its construction of glowing, white Tuckahoe marble in an Italianate style (Gray 1991) (Fig. 2). On its opening day in 1846, Stewart’s was described by James Gordon Bennett in the New York Herald as “exquisitely chaste, classic and tasteful… the most splendid dry goods store in the world” (Gray 1991). Stewart’s was divided in distinct departments and offered a wide inventory of merchandise for sale, supporting the argument that it, and not Bon Marché, was the world’s first department store.

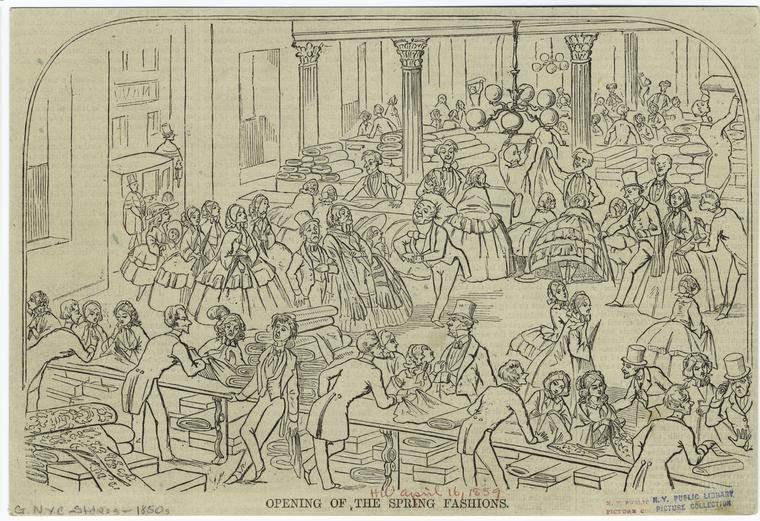

Free entrance without obligation to buy merchandise, a new system offering set prices without haggling with salesclerks, and goods accepted for refunds and exchanges further distinguished department stores from previous retail models. Innovations in transportation, such as street cars, elevated trains, and the beginning of the subway system in 1878 bolstered urbanization and mass production (Whitaker 2006). Department stores in urban centers allowed the customer to purchase a variety of goods under one roof, and encouraged “consumption through the exploitation of visual pleasures” (Edwards 2010). Prior to 1880, most dry goods stores simply hung merchandise on walls and pillars, and did not arrange them in decorative, visually appealing ways (Leach 1994) (Fig. 3). The aesthetic splendor of the department store was truly something new.

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Opening of the Spring Fashions, 1859. New York Public Library Digital Collections: Art and Picture Collection, the New York Public Library. Source: New York Public Library

Department stores with lounges, restrooms, and restaurants, catered to both city-dwelling and suburban women. Their metropolitan locations and luxurious environs enabled shopping to become a leisure activity, and in them women found a new space where they could spend time, unchaperoned and away from their homes. In his book The Ladies’ Paradise (1882), modeled after the Parisian department stores Le Bon Marché, Printemps, and the Louvre (Dimant 2009), Émile Zola describes the diversions offered by these new spaces:

“His creation was a sort of new religion; the churches, gradually deserted by a wavering faith, were replaced by this bazaar, in the minds of the idle women of Paris. Women now came and spent their leisure time in his establishment, the shivering and anxious hours they formerly passed in churches: a necessary consumption of nervous passion, a growing struggle of the god of dress against the husband, the incessantly renewed religion of the body with the divine future of beauty.” (378)

In Counter Cultures: Saleswoman, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890-1940, Susan Porter Benson states:

“By presenting itself as the home of leisure, the department store sought to elevate its agenda beyond commerce, to distinguish itself as the purveyor of middle class taste. Expanding its range of activities with its line of goods, the institution offered to entertain the public while educating them in the latest trends in art, music, dress and home furnishings.” (115)

The stores were a destination where women could socialize and dine, enjoy elaborately beautiful spaces and artfully displayed goods, and, of course, shop.

EMERGENCE OF READY-TO-WEAR

During the early nineteenth century, clothing was crafted by professional tailors, dressmakers, and home sewers. Manufacturing of ready-made clothing began in the mid-1800s due to reorganization of labor and production models, and technological inventions such as the sewing machine. During this time, machine-made lace and embroidery became more affordable, production increased, and the sewing machine became available for home use. Dress patterns were created or copied at home, and fabric, trim, undergarments, and accessories were often purchased from urban department stores. Ready-to-wear menswear first became available as uniforms for the War of 1812, and shortly afterward for civilian clothing (Hollander 1992). The womenswear market was slower to develop, mostly due to the complex construction of women’s garments and the individualized need for a proper fit over a corset.

Ready-to-wear womenswear began with underwear, outerwear, and accessories (Potvin 2009). Cloaks became available in the 1860s, wrappers, petticoats, and chemises in the 1870s, tailored suits in the 1880s and 1890s, shirtwaists in the 1890s and 1900s, and, finally, dresses by the 1910s and 1920s (Gamber 1997, Kawamura 2010).

The ready-to-wear clothing industry democratized fashion by appealing to the needs of a mass audience with its delivery of immediacy and functionality (Potvin 2009). However, the selling of ready-made clothes required a different approach than made-to-order, and did well in department stores with their large spaces, appealing displays, and wide range of merchandise for sale (Gamber 1997).

New York City manufactured relatively affordable ready-to-wear garments by the turn of the twentieth century, but unlike Paris, did not have well-known fashion designers (Kawamura 2010). A nascent desire for American fashion design was brewing, demonstrated by the New York Times’ “Design Contest,” held from December 8, 1912 through January 8, 1913, that sought “proof of American Originality” in competitions among many fashion categories. Ethel Traphagen won first prize, and later headed the Traphagen School of Fashion from 1923 to 1991 (Zachary 2013). By the 1930s several American designers, many of whom had been working anonymously for department store custom salons and private labels for years, began to receive recognition.

Specialty stores’ custom departments, selling made-to-order fashions from Paris to the American consumer, were preferred retailers for upper-class men and women. Clothing was purchased as originals, or created by a dressmaker copying a couturier’s design. Tailoring shops continued to flourish and at-home sewers still created clothes, “although if they lived in an urban environment, they probably bought the fabric and sewing supplies in a department store” (Schorman 2010). At the end of the nineteenth century, Lord & Taylor, among several New York City department stores, had on-site workrooms to produce custom garments.

MAIL ORDER, CATALOGS, & STORE PERIODICALS

The popularity of mail-order catalogs coupled with a more robust postal service increased the availability of ready-to-wear clothing. Montgomery Ward, the first American mail-order catalog, started in 1872, although department stores including Bon Marché had offered free delivery and mail-order services since the middle of the nineteenth century (Kawamura 2010). In a 1908 article titled, “Emancipation from the Dressmaker: Clothes Which Fit Now Sold by Mail, to the Relief of Womankind,” the author writes,

“The mail-order houses make it possible for women everywhere to be entirely well-dressed—and for less money than they could be ill dressed without.” (McCulluch-Williams 1908, 316-319)

It should be noted that mail order prior to the 1910s is not synonymous with ready-to-wear, and women were instructed to provide stores with their measurements to enable a custom fit. By the 1920s, population growth away from urban centers, enhanced transit systems, motorized vehicles, and home telephones allowed consumers to call in orders without going to the store, bolstering the mail order business.

Department stores published catalogs and magazines to advertise their services and products. Modes and Manners, a glossy fashion publication started in 1924, was financed by the Standard Corporation of New York for eight department stores. Modes and Manners appealed to the suburban market, and only the advertisements differed for each store’s version (Leach 1994). In 1927 while working from Paris to report on collections, Muriel King, by then a celebrated illustrator, sketched clothing for Modes and Manners, in addition to contributing to magazines such as Vogue. Modes and Manners, while primarily fashion-focused, included progressive articles about politics and successful women, yet “tried to lead readers to believe that if they only bought the right bathroom accessories or the most up-to-date dining-room china, they would be carried off to ‘glamorous worlds’ and achieve the social ‘status’ of a Consuelo Vanderbilt or of a Dorothy Parker” (Leach 1994, 310).

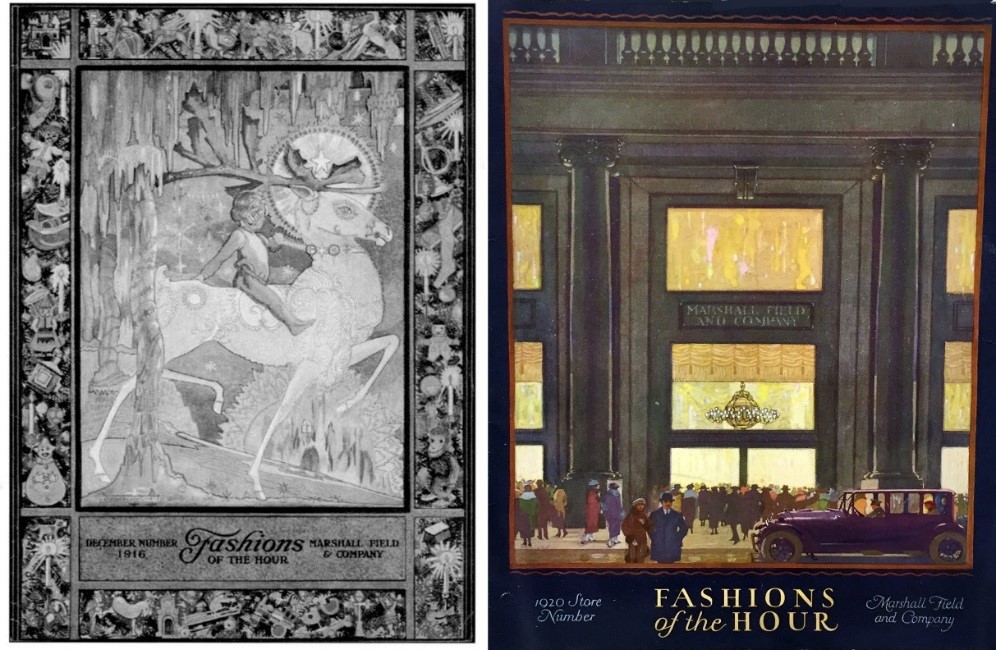

Fig. 4 - Fashions of the Hour. Marshall Field’s catalog: Fashions of the Hour, December 1916 and Winter 1920. Source: Marshall Field's

In 1914, Marshall Field’s in Chicago published Fashions of the Hour on a bi-monthly basis (Leach 1994) (Fig. 4). Charm, a glossy magazine published by Bamberger’s department store between 1924 and 1932, was targeted toward New Jersey’s middle and upper class women. Charm’s circulation reached 83,000 its first year, and according to Women’s Wear in 1925, Charm was legitimate as a stand-alone publication:

“Store activities are not discussed even by subtle means. Excepting for several pages which present fashionable apparel carried by Bamberger’s—and the name is confined to the last line of copy—the paper is free of the Bamberger label…The development of Charm simply furnishes more proof of the changes in promotional methods that have been recorded in the last few years. The thought of becoming more firmly impressed on store executives is that selling the institution is quite as remunerative in the long run as selling the goods that are featured in the newspapers from day to day.” (Leach 1994, 310)

Muriel King and other recognized artists contributed to Charm, and it, like contemporaneous store-funded publications, aimed to appeal to the modern woman.

DEPARTMENT STORE GROWTH & LAYOUT

Before department stores existed, most large dry goods stores used their first and second floors to sell goods, and higher floors were used for workshops, storage, and wholesale space. In the nineteenth century, silks and other dry goods were sold on the ground floors of department stores, but the ready-to-wear market of the twentieth century pushed fabrics to higher floors. Between 1909 and 1914, dry goods were removed from the main floor of most department stores (Whitaker 2006).

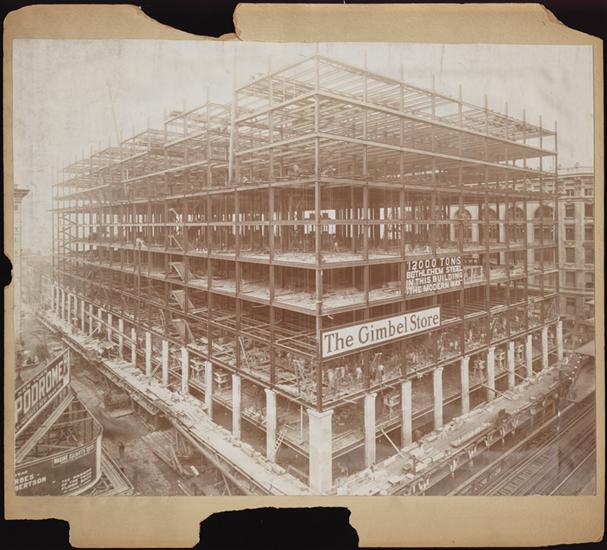

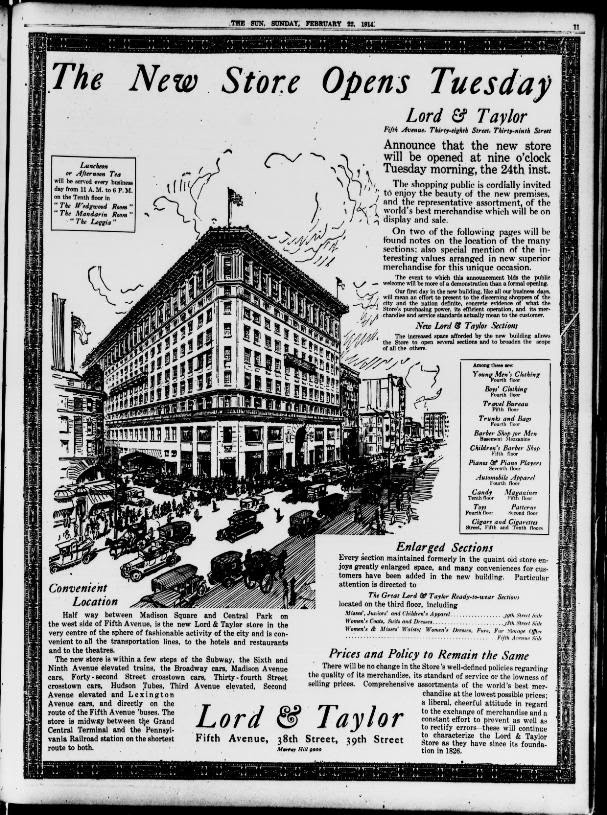

The price of land increased as department stores evolved in New York City, and spaces were utilized vertically; the influx of taller buildings created the need for elevators and escalators. Lord & Taylor and Jordan Marsh installed elevators as early as the 1860s, and by the 1880s elevators became necessary as stores reached at least four and five stories high (Whitaker 2006) (Figs. 5-6).

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Construction of Gimbels department store, ca. 1910. Photograph. New York: Museum of the City of New York. Source: Museum of the City of New York

Fig. 6 - Lord & Taylor. Lord & Taylor advertisement, February 22, 1914. Library of Congress: The Sun. Source: Library of Congress

The grand size of department stores at the turn of the twentieth century is exemplified by Bamberger’s in Newark, open in 1892 at 20,000 square feet and expanding to 500,000 square feet in 1912. Called “the Great White Store,” Bamberger’s growth was typical for department stores in America, “not just in terms of the stores’ rapid ascent at the turn of the twentieth century but also in their continued expansion after WWI” (Longstreth 5).

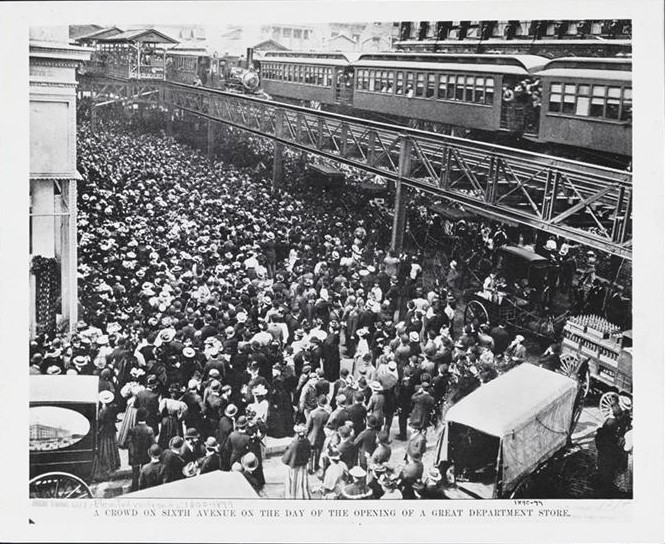

On September 14, 1896, Siegel-Cooper Company opened on Sixth Avenue between Eighteenth and Ninetieth Streets, and “the Big Store” was 750,00 square feet (Iarocci 2014) (Figs. 7-8).

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. Opening of Siegel and Cooper's Department Store, ca. 1896. Museum of the City of New York. Source: Museum of the City of New York

Fig. 8 - Bryon Company. Entrance to Siegel Cooper Dry Goods Store at 18th Street and 6th Avenue, 1900. Museum of the City of New York. Source: Museum of the City of New York.

The store employed 3,000 workers and had 120,000 visitors daily. Siegel-Cooper was arranged with menswear, hats, books, and dry goods on the main floor, womenswear on the second floor, furniture and rugs on the third floor, and food—including groceries and canned goods from an on-site facility—on the fourth floor (Iarocci 2014).

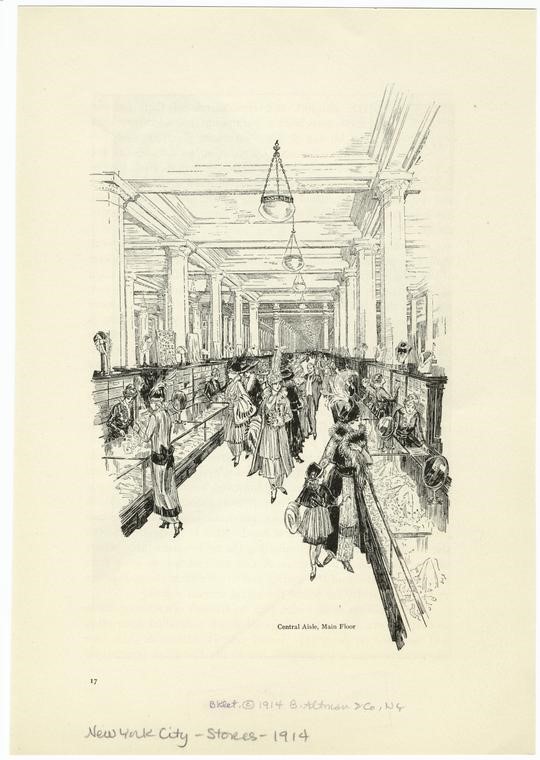

Siegel-Cooper included a post office and telegraph service, restaurant, barber shop, hairdresser, nursery, infirmary, dental office, stockrooms, and employee offices. The roof had a garden and observatory, and there was a machinery room with an engine to run the entire operation. Siegel-Cooper introduced bigger aisles in the mid-1880s, attracting customers to the store from the street (Leach 1994) (Fig.9).

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown. Central Aisle, Main Floor, 1914. New York: The New York Public Library. Source: The New York Public Library

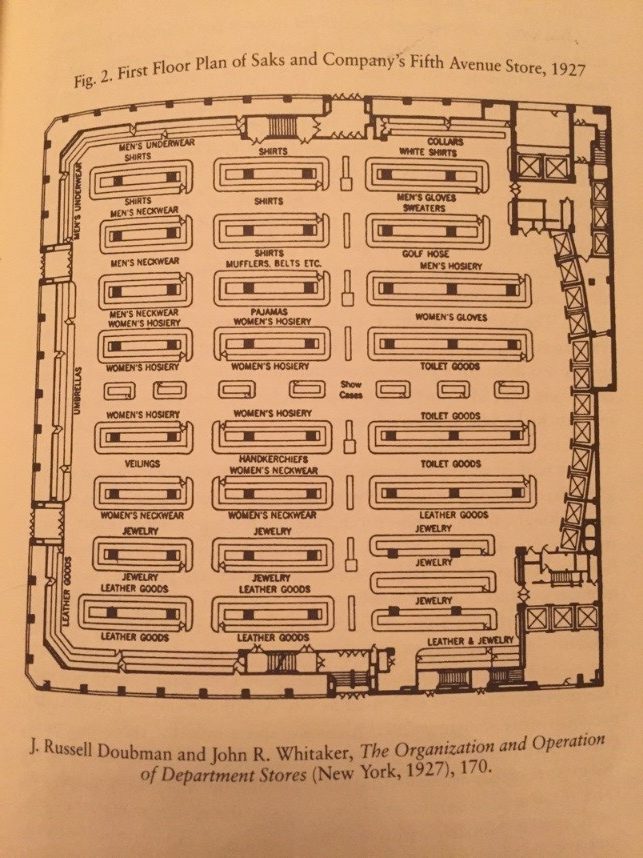

Fig. 10 - J. Russell Doubman and John R. Whitaker. First Floor Plan of Saks and Company's Fifth Avenue Store, 1927. Source: Susan Porter Benson, Counter Cultures: Saleswoman, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890-1940

It was the world’s largest store during the time, but other department stores boasted their size and variety of services through advertisements. The men’s section of Lord & Taylor’s new 1914 flagship building advertised:

“Make your purchases, be shaved and manicured, change your clothing, if you like, and leave without passing through any of the departments where women’s goods are sold.” (The Evening World 1914)

Wanamaker’s, originally from Philadelphia with a New York branch by 1907, began in 1877 as a one-room shop of 2,500 square feet. The New York store included “three complete exclusive stores: the women’s store in the Stewart building; the men’s store occupying the main floor of the new annex; and, in its upper sales floors, ‘the Galleries of Furnishing and Decoration,’ a series of domestic rooms decorated in popular period styles as a model for designers and homemakers” (Leach 1994, 115). Wanamaker’s doubled or tripled in size each decade between the 1880s to 1930 (Leach 1994). The compartmentalized layout allowed customers to access goods specifically within their needs, but did not cater to impulse shopping.

There was not one single standard floor plan, but by the 1930s most department stores had a typical layout: dry goods and bargains in the basement, and cosmetics and accessories on the main floor (Fig. 10). The deliberate arrangement offered:

“glamour and impulse items to waylay women on their way to the upper floor—and clothing and furnishings for men who were presumed too timid to venture farther into the store.” (Benson 1986, 44)

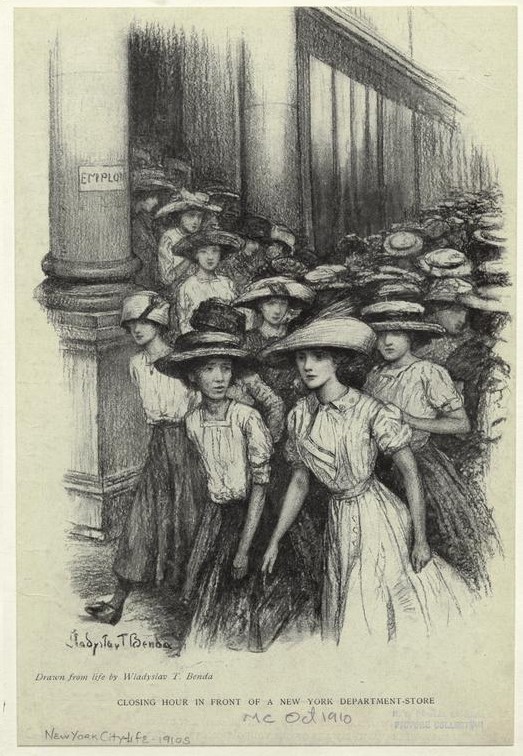

Women’s apparel and underwear were sold on the second floor (Whitaker 2006), and higher floors included children’s wear, toys, and home good such as glassware and china. Furniture and rugs were sold on upper floors. Informal lunch counters were typically in the basement, and restaurant and tea rooms were on the top floor. Wanamaker’s and Macy’s both had restaurants by late 1870s (Whitaker 2006), and unescorted women could not be served (Fig. 11).

For more, see Part 2 of this essay which discusses the roles of salesclerks and anonymous fashion designers who worked for department store labels.

Fig. 11 - Benda T. Wladyslaw. Closing Hour In Front Of A New York Department-Store, 1910. Digital Public Library of America.. Source: Digital Public Library of America.

References:

- Benson, Susan Porter. Counter Cultures: Saleswomen, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890-1940. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/472725919.

- Dimant, Elyssa. “From ‘Paradise’ to Cyberspace: the Revival of the Bourgeois Marketplace,” in The Places and Spaces of Fashion, 1800-2007, ed. John Potvin. New York: Routledge, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/826856012.

- Edwards, Bronwen. “Department Store.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2018. https://www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com/products/berg-fashion-library/encyclopedia/the-berg-companion-to-fashion/department-store.

- The Evening World, February 17, 1914. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress. Accessed September 4, 2018. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030193/1914-02-17/ed-1/seq-4/.

- Gamber, Wendy. The Female Economy: the Millinery and Dressmaking Trades, 1860-1930. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/606037542.

- Gray, Christopher. “No Restoration in Sight for ‘the Big Store,” New York Times, October 27, 1991. Accessed Septermber 4, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/108641071?accountid=27253.

- _________. “Streetscapes/The A.T. Stewart Department Store; A City Plan to Revitalize the 1846 ‘Marble Palace,’ New York Times, March 20, 1994. Accessed September 4, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/03/20/realestate/streetscapes-stewart-department-store-city-plan-revitalize-1846-marble-palace.html

- Hollander, Anne. “The Modernization of Fashion,” Design Quarterly, no. 154 (Winter 1992): 27-33. Accessed September 4, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4091263.pdf.

- Iarocci, Louisa. The Urban Department Store in America. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1022641719.

- Kawamura, Yuniya. “The Fashion Industry,” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Global Perspectives, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Phyllis G. Tortora, 191–203. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch10025.

- Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture. New York: Vintage Books, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1031962769.

- Longstreth, Richard W. The American Department Store Transformed, 1920-1960. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/427757209.

- McCulluch-Williams, Martha. “Emancipation from the Dressmaker: Clothes Which Fit Now Sold by Mail, to the Relief of Womankind,” Good Housekeeping, vol. 47, issue 4 (September 1908): 316-319. Accessed September 4, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1715348131?accountid=27253.

- Potvin, John, ed. The Places and Spaces of Fashion: 1800-2007. New York: Routledge, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/826856012.

- Schorman, Rob. “The Garment Industry and Retailing in the United States.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: The United States and Canada, edited by Phyllis G. Tortora, 87–96. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch3014.

- Whitaker, John. Service and Style: How the American Department Store Fashioned the Middle

Class. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865093390. - Zachary, Cassidy. “Ethel Traphagen: American Fashion Pioneer,” Diss., Fashion Institute of Technology, 2013. Accessed September 4, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1687190108?accountid=27253.

- Zola, Émile. The Ladies’ Paradise. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/811729045.