Part 1 of this essay covers the emergence of department stores in New York City during the nineteenth century and can be read here. Part 2 discusses the roles of salesclerks and anonymous fashion designers who worked for department store labels.

Salesclerks

In the January 1899 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal, Emma M. Hooper describes the lack of ability among most women to “shop with economy, taste and prudence…all could learn to distinguish good from bad, real from imitation and to discern whether they are getting an article of cotton or wool, or a skillfully prepared mixture that will appear well and wear badly,” (Iarocci 2014, 156). Readers of women’s popular magazines were encouraged to hone their shopping skills with headlines such as, “The Shopper as Seen by the Salesgirl: Told by the Girl Herself” (Ladies’ Home Journal 1908), “How to Use the Fashion Department” (Good Housekeeping 1926), “The Secret Back of Fifth Avenue” (Ladies’ Home Journal 1913), and “Milady Goes Shopping” (Red Book 1923).

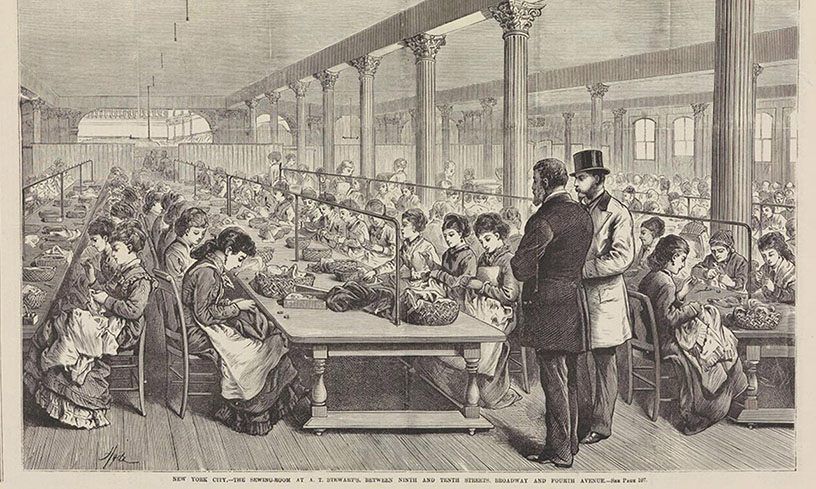

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Shop-Girls, 1880. Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections. Source: Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections

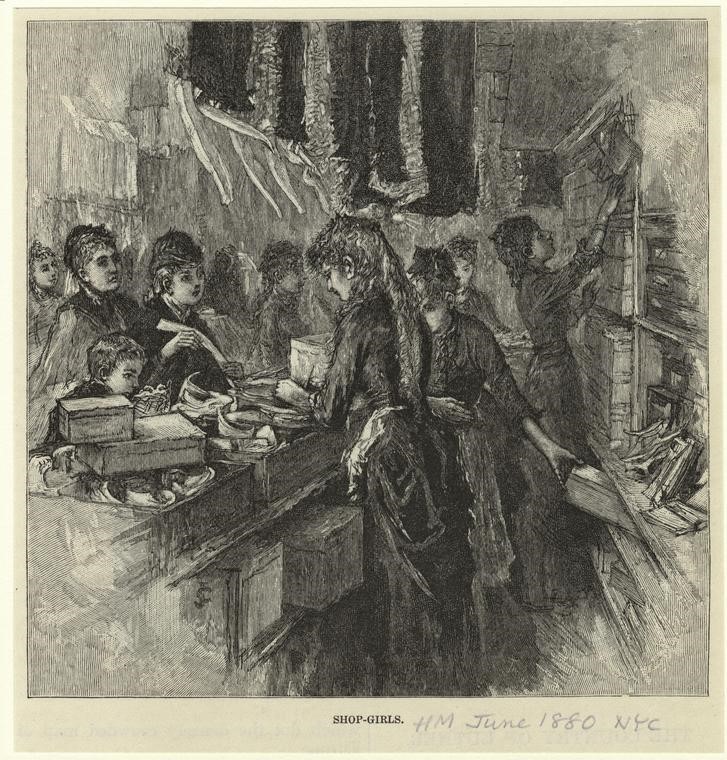

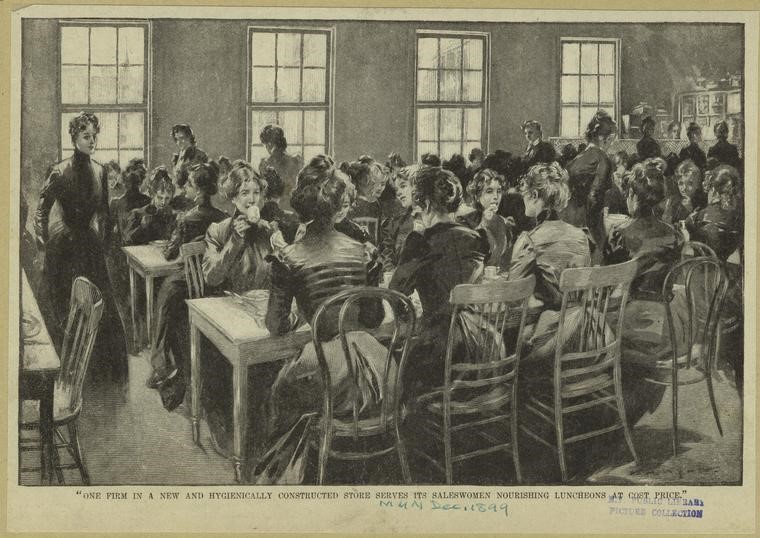

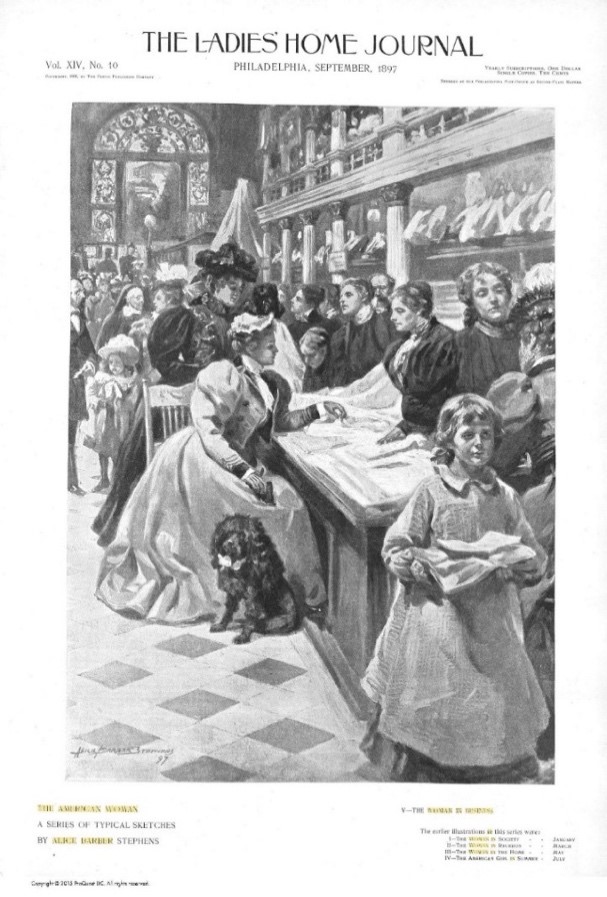

Staff, attending to shoppers’ needs, were a large part of the department store experience. By the 1880s, women working in department stores increased more than any other job, and department store staff were mostly working class and female by the 1890s (Benson 1986). In the 1920s, store sales was one of the three female occupations available for middle class women (Figs. 1-3). Alice Barber Stephens produced a six-part painting series titled “The American Woman” for Ladies’ Home Journal in 1897 (Fig. 4). The paintings focused on middle-class Philadelphia women at home and in the economic sphere, such as a “Woman in Business” painting set at Wanamaker’s. The busy store scene of shoppers and salesclerks depicts the differences between the leisure and working classes. Department store buyers, unlike clerks, had privileged status among the ranks, and their work offered upward mobility for the women who constituted one-third of buyers by 1915. Buyers for stores with high-end clothing departments visited Paris to view collections and, in turn, influenced fashion tastes at home.

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. One Firm In A New Hygienically Constructed Store Serves Its Saleswomen Nourishing Luncheons At Cost Price, 1899. Source: Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. The Lunch-Room At A. T. Stewart’s, Between Ninth And Tenth Streets, Broadway And Fourth Avenue, 1875. Source: Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections

Several films from the early twentieth century feature sales girls as fictional characters among backdrops of department stores. The 1927 silent film It directed by Clarence Badger stars Clara Bow as a working class shop girl at Waltham’s, “the world’s largest store.” Bow’s character develops a crush on the owner’s son, a wealthy store manager, and the two pursue a relationship among their class differences. In one scene, realizing she does not have a proper evening gown, Bow’s character uses scissors to alter the dress she has been wearing all day to create something suitable. In the 1930 film Our Blushing Brides starring Joan Crawford, three New York City shop girls share an apartment, each making no more than twenty dollars per week. Both films portray working class salesclerks interacting with demanding customers and upper-class suitors, and “the popularization of this archetypal character as a public figure reflects the intensification of the role of consumption as a defining practice of modernity” (Iarocci 2014).

Fig. 4 - Alice Barber. The American Woman, 1897. Source: Ladies' Home Journal 14, no. 10, September 1897: 1

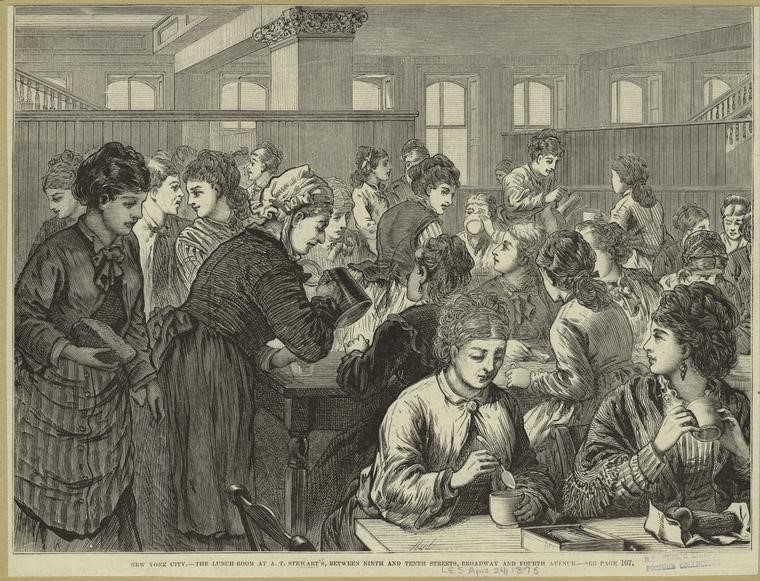

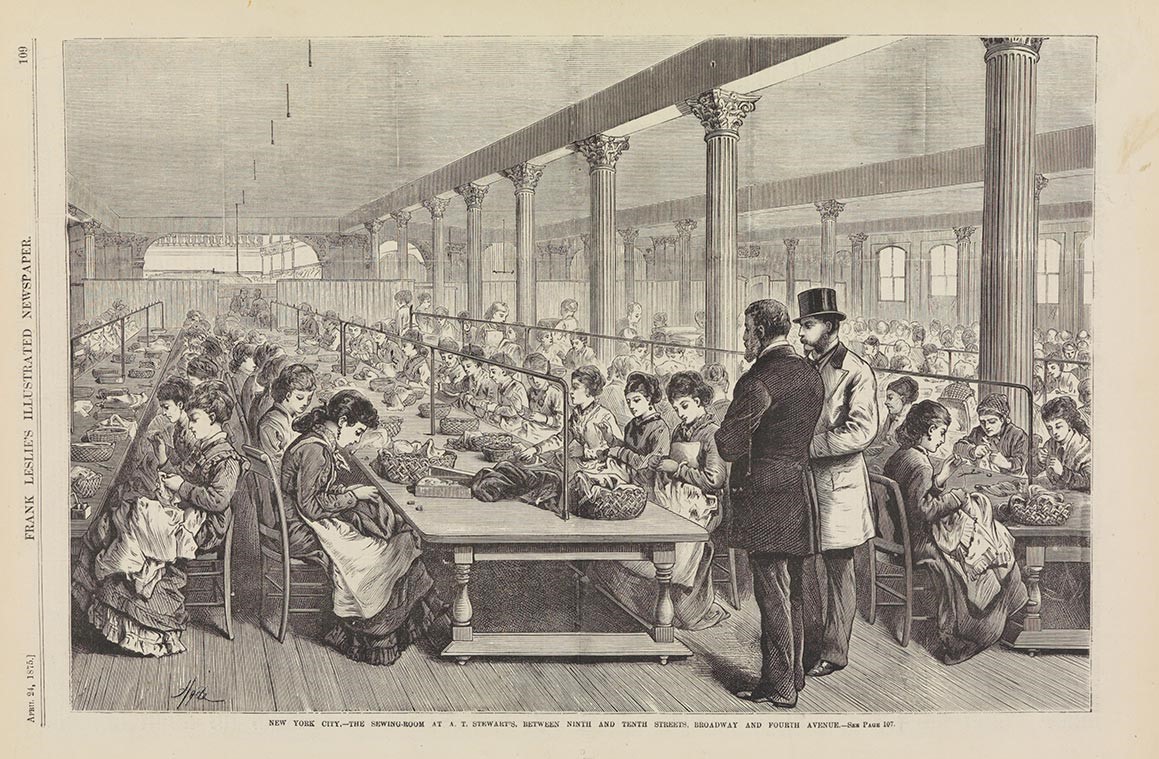

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. The Sewing Room at A.T. Stewart’s, April 24, 1875. Source: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper

Store Labels, Anonymity & American Fashion Designers

T

here is a symbiotic relationship between department stores and the haute couture, and as Rebecca Arnold explains,

“While ready-to-wear clothes had been developing independently of Parisian haute couture since the 17th century, it was not until the 1920s that they were designed and marketed principally on their fashion values, rather than their price or quality” (Arnold 2009, 21).

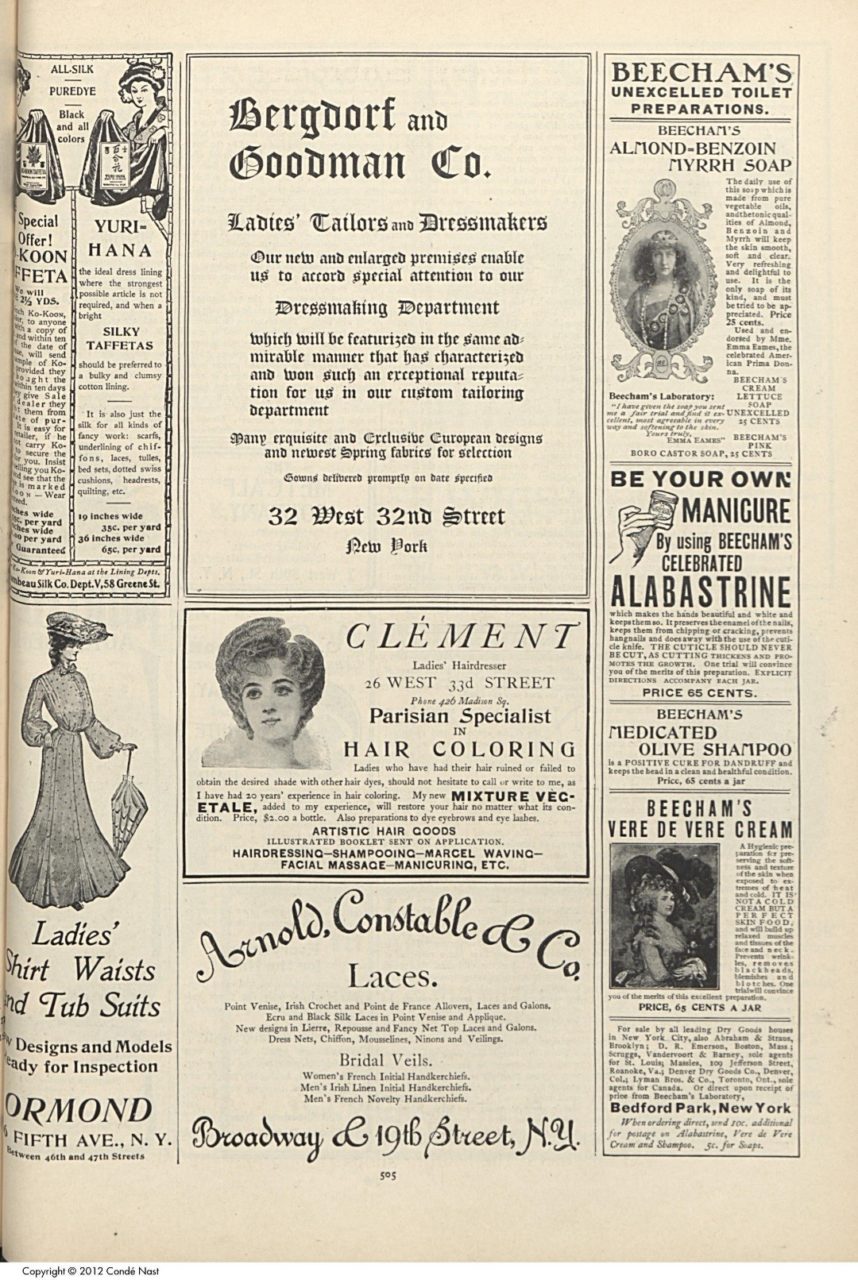

Couturiers made agreements with department stores to sell their garments, and in America, department stores hired designers to work anonymously for their store brands (Figs. 5-6). High end department stores with custom salons including Saks Fifth Avenue, Bergdorf Goodman, and Bonwit Teller reproduced Parisian couture. They also used their in-house designers to create original fashions for clients, advertising garments as “designed exclusively” for the store (Fig. 7). As early as 1901, Abraham and Strauss introduced its “new salon of dress” (Gamber 1997) (Fig. 8), modeled in an ornate European style. “French rooms,” housed in custom dressmaking and millinery departments, were “special showrooms that admitted only the most elite clientele” (Gamber 1997, 195), and “offered a refuge for wealthy customers repelled by the ‘democratic’ tendencies of the department store” (Gamber 1997, 195).

Fig. 6 - Lord & Taylor. Evening dress produced in Lord & Taylor’s on-site workroom, 1900-1902. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 7 - Bergdorf Goodman. Bergdorf Goodman advertisement for its dressmaking department in Vogue, April 14, 1904. Source: Vogue

Fig. 8 - Wexler & Abraham. Evening dress, Wexler & Abraham, Brooklyn, NY, ca. 1880. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

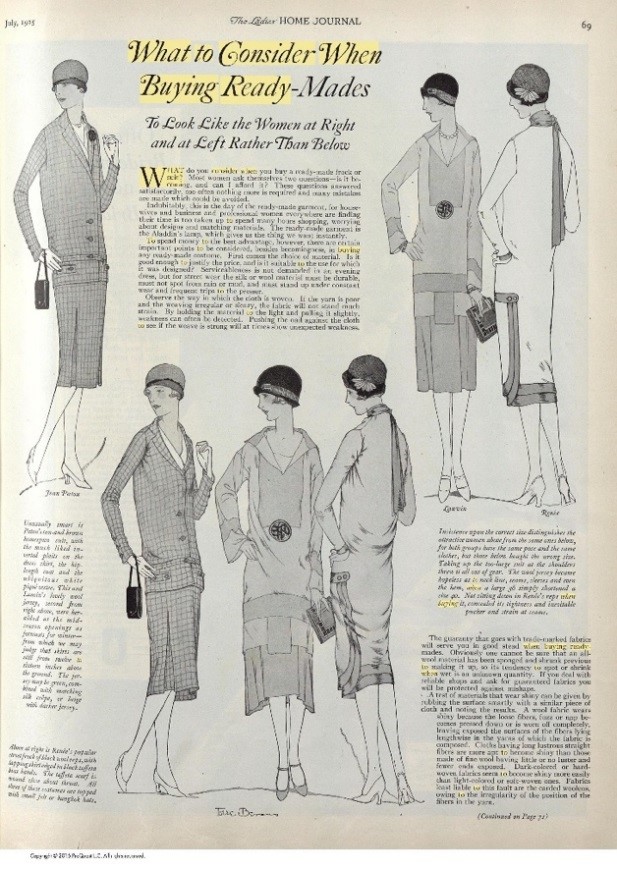

In the early twentieth century, salesclerks created fifty percent of the workforce, while milliners (Arnold 2009) and dressmakers composed less than five percent (Gamber 1997). Lilly Daché, a Parisian trained milliner, worked in the Macy’s millinery department in the 1920s. Dressmaking and millinery work offered a steadier pay than retail, and workrooms, often on high floors, had better light and air circulation. By the 1910s, middle class shoppers were likely to purchase less expensive ready-made clothing from department stores. Women’s publications offered advice such as “What to Consider When Buying Ready-Mades,” instructing readers how to avoid ill-fitting garments with illustrations to help one “look like the woman at right and left rather than below” (Harland 1925) (Fig. 9). Alterations were required during the early years of ready-to-wear, and only with the assistance of “hired hands” could mass-produced clothing compete with the skills of the dressmaker. Department stores offered free or low cost alterations, keeping prices much cheaper than custom made (Gamber 1997) and exclusive stores employed “fitters” to plan the alterations and “hands” to implement them (Gamber 1997).

Fig. 9 - Ladies' Home Journal. What to Consider When Buying Ready-Mades, July 1925. Source: Ladies' Home Journal

Fig. 10 - Bergdorf Goodman. "An original creation by Bergdorf Goodman," advertisement in Vogue, February 15, 1926. Source: Vogue Archive

In her autobiography Fashion is Spinach, Elizabeth Hawes describes her work at Bergdorf Goodman as an unpaid apprentice in the workroom in 1924. She worked eleven hour days “on the top floor with the skylights letting in all the mid-summer sun. I was so tired I cried every night when I got home. I learned how expensive clothes were made to order” (Hawes 1938, 30) (Fig. 10). Hawes depicts the differences between made-to-order garments from specialty stores and ready-to-wear from department stores. The shopper at the specialty store “will not have to spend an hour getting through three blocks of traffic to the door. The made-to-order lady should not have to smoke seven cigarettes and tap her foot a thousand and fifty times while a half hour elapses between 57th and 56th street” (Hawes 1938, 123). The “inexpensive lady’s” shopping experience, on the other hand, is “the nerve-wracking business of squeezing herself into a five by eight fitting room to try on a lot of things she doesn’t like anyway, and she knows on walking into a department store, that she can’t get navy blue in the fall, which is enough to unsettle the most stable stomach” (Hawes 1938, 124). Hawes’ preference is naturally for the quality of service and finery found at shops like Hattie Carnegie and Bergdorf Goodman’s (Fig. 11) custom salons, selling made-to-order fashion and interpreting European style for a discerning American audience. The offerings at the department stores in 1928, Hawes felt, was in stark contrast,

“It was bad in quality and cheated on cut. It was Vionnet’s best model with a bow added to it for the purpose of attracting the American eye. It was junked up and tricked out and tawdry” (Hawes 1938, 125).

Fig. 11 - Design unknown. Evening dress, ca. 1929. Source: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Most American designers, including Elizabeth Hawes, did not gain recognition until the 1930s. However, some designers were credited by name for their work, like E.M.A. Steinmetz, designer for Stein & Blaine until 1932 and art director of Harper’s Bazaar. Steinmetz was regularly interviewed in trade publications for her fashion predictions, and in a 1920 story about the revival of the lingerie gown (“the frilliest summer seen since 1912”), Women’s Wear calls her “one of the best known designers of clothes in New York” (Women’s Wear, March 18, 1920).

In 1925, two years prior to becoming the New Yorker’s fashion editor, journalist Lois Long began a column called “Feminine Fashions” for the magazine. Long often wrote about clothes available at New York department stores, but did not identify designers in her column until later. Another column of Long’s, “On and Off the Avenue,” starting in 1925 and lasting until her retirement in 1970, discussed department stores (Robertson 2017). In 1925 Long wrote:

Any woman who has faultless taste, a reasonable amount of time to spend on her shopping, and a good figure, can dress, and dress very well, for a ridiculously small amount of money. If you have taste, you can tell where to remove or to add an ornament, where to take in a dress or let it out and give it just the right line, and how to give just the right fillip to a hat brim and thereby avoid looking like the little girls that pour out into Forty-second Street at the lunch hour…Some of the best women I know, haunt Stewart’s, where they occasionally find an evening dress costing less than fifty dollars that can be made, with little effort, to look like one costing three times that amount; they journey to the economy floor of Russek’s; to Adevon’s; and to the cheap dress departments of Macy’s or Gimbel’s or Saks-Herald Square (Long 1925).

Long advises the reader to “pick out the very simplest thing that these shops have in stock, to remove all pieces of lace, artificial flowers, buttons, braid and superfluous flounces from it, and to add, if you must add something, very nice accessories of your own” (Long 1925). Steinmetz, too, preferred the simplicity that was in style during the 1920s, and stated “costliness has really no relation to the style or charm. A simple thing is often in better taste than an extremely expensive one” (Women’s Wear 1918).

After decades of working under store labels, many American designers began to receive credit for their work. Some notable designers include: Sophie Gimbel at Saks, Fira Benenson at Bonwit Teller, who led their couture salon from 1934 to 1948, and Muriel King for Stein & Blaine. In 1932 King designed for Lord & Taylor, selling both her original fashions and copies, and King designed an entire line for B. Altman in 1933. Bergdorf Goodman’s Peggy Morris, Leslie Morris, Mark Mooring (Fig. 12), and Ethel Frankau all found eventual recognition. Frankau worked as both a buyer and designer for Bergdorf Goodman starting in 1914, and her “designs under the Bergdorf label were very important in developing the store’s reputation as a source for beautiful, American-designed clothing” (Aisling 2015). According to Edwin Goodman, Bergdorf Goodman’s made-to-order originals always outsold their Paris imports since they “are not so quickly copied [and are therefore] more exclusive” (Aisling 2015). In 1919, the New York Tribune called Frankau’s designs “an apt example of the creative genius of young America” (Aisling 2015). Frankau became the director of Bergdorf Goodman’s custom salon for nearly sixty years.

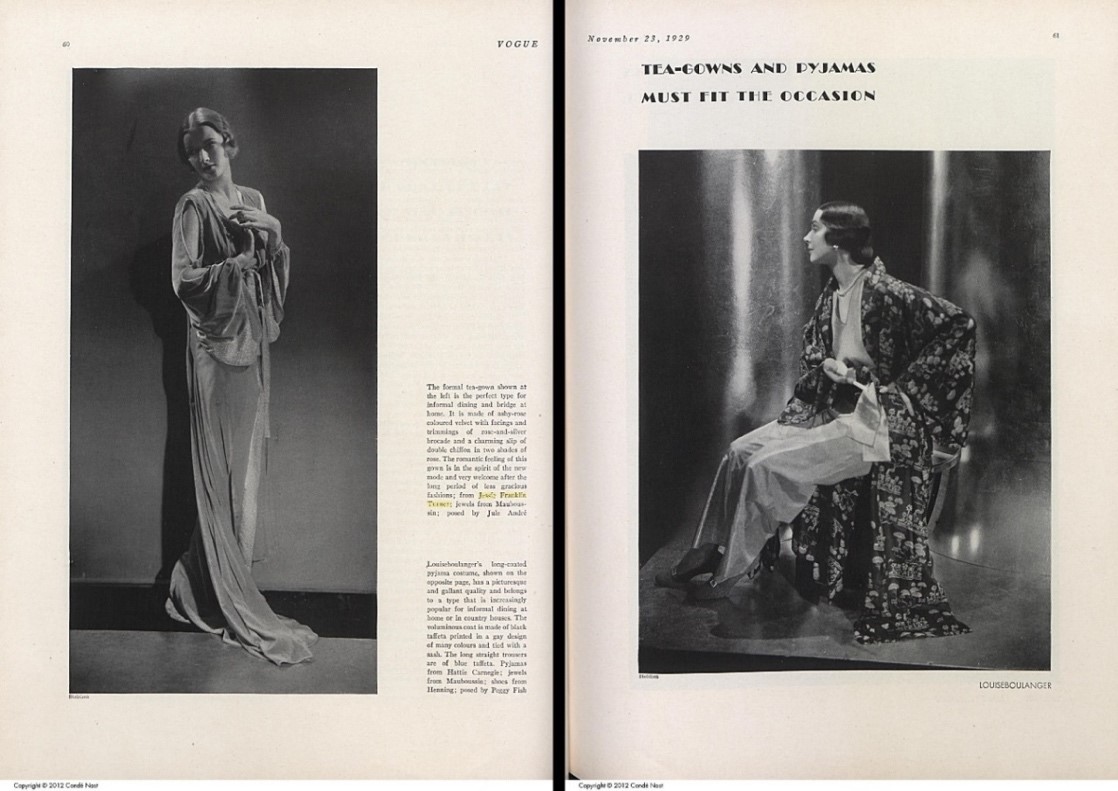

Another designer with department store origins is Jessie Franklin Turner. Turner worked for Bonwit Teller’s custom salon from 1916 to 1922 (Hill 2007), and left to establish her own successful couture business. Early in her career she worked under the name “Winifred Warren, Inc.” (Hill 2007) (Figs. 13-14). Norman Norell worked at Hattie Carnegie from 1928 to 1940, starting the year Carnegie began her first ready-to-wear line. By this time Hattie Carnegie, initially a specialty store, had grown to the size of a small department store. Norell’s work there was done in “’complete anonymity,’ modifying elements of Paris couture for American ready-to-wear designs. During these early years, Norell learned about cut, fit, and quality fabrics, as seasonal trips to view the Paris collections exposed him to the standards of couture” (Museum at FIT). In 1940, Norell left Hattie Carnegie to work for Traina-Norell. He said, “[Traina] offered me a larger salary if my name were not used, a smaller amount if it were” (Museum at FIT), and he chose the latter. Norell designed for Traina-Norell for twenty years, and left in 1960 to start his own label.

Fig. 12 - Mark Mooring. Evening dress, ca. 1930. Source: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 13 - Attributed to Bonwit Teller & Co. Jessie Franklin Turner. Evening dress, ca. 1920. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.. Source: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Fig. 14 - Jessie Franklin Turner. Jessie Franklin Turner’s tea-gowns and pajamas featured in Vogue, November 23, 1929: 60-61.. Source: Vogue Archive

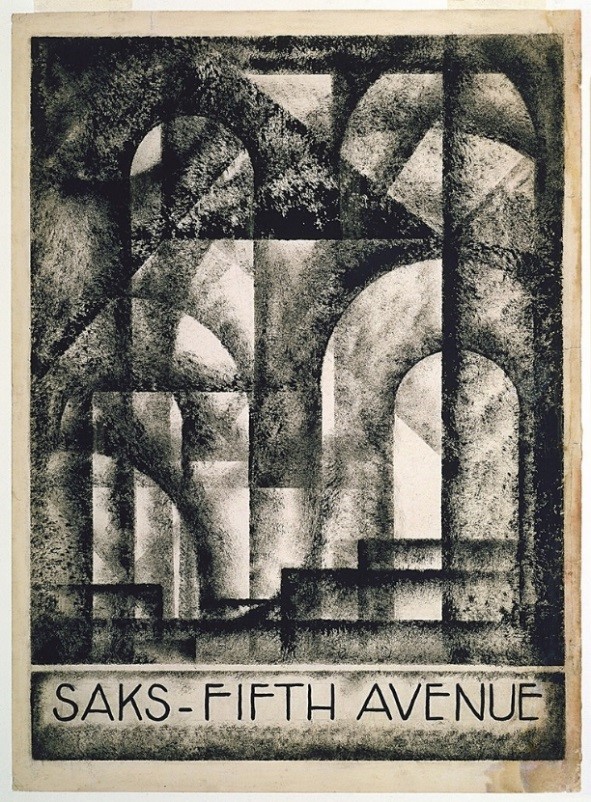

During the late 1920s, department stores were refreshing their images, and by embracing modernity they helped introduce new design to the American public. In 1928, inspired by the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris, Dorothy Shaver at Lord & Taylor installed an “Exposition of Modern French Decorative Art.” Furniture and household accessories created by French companies were displayed in the new, modern style. Artworks by French artists including Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso were exhibited among the decorative arts, and the show successfully presented the avant-garde aesthetic to a middle-class American audience. Saks, too, incorporated the modern art and design movement into their stores, and in 1927 commissioned artist Donald Deskey to create window displays and advertising brochure covers (Fig. 15). The strong geometrical patterns on Deskey’s brochure for the store, influenced by European modernist artists including Braque, “not only brought modern design to the attention of Americans, but it made modern design part of what it meant to be middle class.”

Fig. 15 - Various. Fashions of Lord & Taylor featuring various American designers, 1933. New York: Museum of the City of New York. Source: Museum of the City of New York

By the early 1930s Lord & Taylor began to promote American fashion designers by name. The store’s “American Look” program, launched by Shaver in 1932, featured more than young sixty designers over the span of seven years. Bonnie Cashin, Clare Potter, Claire McCardell, Elizabeth Hawes, Muriel King, Nettie Rosenstein, Norman Norell, and Pauline Trigere are among those included (Fig. 16). Shaver’s vision and support provided a platform for American designers, and helped foster recognition for those who had been working in obscurity for decades. The advent of American sportswear further developed the landscape of retail, and on the cusp of the 1930s department stores, dramatically different from their origins eighty years prior, were poised to evolve.

Fig. 16 - Donald Deskey. Donald Deskey design for Saks Fifth Avenue brochure, 1927-1928. New York: Cooper Hewitt. Source: Cooper Hewitt

References:

- Arnold, Rebecca. Fashion: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1053418374.

- _________. “North American Influences on West European Dress.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe, edited by Lise Skov, 442–443. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Accessed September 27, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch8073.

- Austin, Annette. “When Woman Buys,” Good Housekeeping, Vol. 49, issue 6 (December 1909): 624-632. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1807572033?accountid=27253.

- Austrian, Della. “How Shoppers Can Help Girls in Stores,” Ladies’ Home Journal, November 1906: 23. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1715471244?accountid=27253.

- Badger, Clarence, dir. It. DVD. New York, N.Y.: Kino on Video, c2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/969440045.

- Barber, Alica Stephens. “The American Woman,” Ladies’ Home Journal 14, no. 10 (09, 1897): 1. Accessed December 1, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1715570285?accountid=27253.

- Beaumont, Harry, dir. Our Blushing Brides. DVD. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, [1930]. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/880174824.

- Bellafante, Gina. “Big City: Lord & Taylor, WeWork and the Death of Leisure,” The New York Times, October 27, 2017. Accessed November 1, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/27/nyregion/lord-taylor-wework-and-the-death-of-leisure.html?emc=eta1&_r=0.

- Benson, Susan Porter. Counter Cultures: Saleswomen, Managers, and Customers in American Department Stores, 1890-1940. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/472725919.

- Blum, Dilys and Kristina Haugland. Best Dressed: Fashion from the Birth of the Couture to Today. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/313782020.

- Breward, Christopher. The Culture of Fashion: A New History of Fashionable Dress. Studies in Design and Material Culture Series. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/945218701.

- Cooper Hewitt. “Donald Deskey Design for Saks Fifth Avenue Brochure, 1927–28.” Cooper Hewitt,accessed December 14, 2018, https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2014/05/05/a-window-into-the-1920s/.

- DeMille, Cecil, dir. Why Change Your Wife. DVD. Paramount, Image Entertainment, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1029303342.

- Devorkin, Jopseh. Great Merchants of Early New York: ‘The Ladies’ Mile.’ New York: Society for the Architecture of the City, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/20902591.

- Dimant, Elyssa .“From ‘Paradise’ to Cyberspace: the Revival of the Bourgeois Marketplace, in The Places and Spaces of Fashion, 1800-2007, Potvin, John, ed. Potvin, John, ed. New York: Routledge, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/800679075.

- Edwards, Bronwen. “Department Store.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com/products/berg-fashion-library/encyclopedia/the-berg-companion-to-fashion/department-store.

- “The Excellence of Ready-Made Clothes.” Good Housekeeping, vol. 69, issue 3, 1909: 86-89, 169, 178, 189. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1807534994?accountid=27253.

- Finamore, Michelle Tolini. Hollywood Before Glamour: Fashion in American Silent Film. Palgrave Macmillian, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/930993446.

- Gamber, Wendy. The Female Economy : the Millinery and Dressmaking Trades, 1860-1930. Urbana : University of Illinois Press, c1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/34878874.

- Gilbert David. “Urban Outfitting: The City and the Spaces of Fashion Culture.” In Fashion Cultures: Theories, Explorations, and Analysis, edited by Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church Gibson, 7–24. London: Routledge, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/850338155.

- Gleason, C. M. “Bernard Newman: The Forgotten Designer of New York and Hollywood.” Diss., Fashion Institute of Technology. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1684588459?accountid=27253.

- Good Housekeeping. “How to Use the Fashion Department,” (1926, 06). Good Housekeeping, June 1926, 82, 70. Accessed December 10, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1813188031?accountid=27253.

- Green, Nancy L. Ready-To-Wear and Ready-To-Work: A Century of Industry and Immigrants in Paris and New York. New York: 1997. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/231704214.

- Harland, Allen. “What to Consider When Buying Ready-Mades: To Look Like the Woman at Right and Left Rather Than Below,” Ladies’ Home Journal, July 1925; 42, 7. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1876359508?accountid=27253.

- Hawes, Elizabeth. Fashion is Spinach. New York: Random House, 1938. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1061812010.

- Hendrickson, Robert. The Grand Emporiums: The Illustrated History of America’s Great Department Stores. New York: Stein & Day, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/11476450.

- Herrick, Christine Terhune. “What New York Women Eat When They Shop,” Ladies’ Home Journal, June 1909, vol. 26, issue 7: 62-63. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1715532780?accountid=27253.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. As Seen in Vogue: A Century of American Fashion in Advertising. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/876672122.

- Hollander, Anne. “The Modernization of Fashion,” Design Quarterly, no. 154 (Winter 1992): 27-33. Accessed December 20, 2018. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4091263.pdf.

- _________. Seeing Through Clothes. New York: Viking, 1978. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/838278112.

- Iarocci, Louisa. The Urban Department Store in America. Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1022641719.

- Joe, Aisling. (2015). “Bergdorf Goodman’s Supreme Court Justice of Fashion: a Chronology of Ethel Frankau’s Career 1914 – 1967.” Diss., Fashion Institute of Technology, 2015. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1735766167?accountid=27253.

- Kaylin, Alexander. “Store Issues Magazine Devoted to Home Interests.” Women’s Wear, Jun 6, 1925: 14. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1677117206?accountid=27253.

- Ladies’ Home Journal. “The Shopper as Seen by the Salesgirl: Told by the Girl Herself,” Ladies’ Home Journal, May 1908: 25, 6. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/wma/docview/1715472546/fulltext/503E059156164792PQ/1?accountid=27253.

- Lancaster Bill. The Department Store: A Social History. London and New York: Leicester University Press, 1995. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/248747737.

- Leach, William. Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture. New York: Vintage Books, 1994. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1066933685.

- Ley, Sandra. Fashion for Everyone: The Story of Ready-to-Wear. New York: Scribner’s, 1975. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/940001234.

- Lois Long, “Feminine Fashions,” The New Yorker, September 14, 1940, 60.

- _________. “On and Off the Avenue,” The New Yorker, November 14, 1925, 28-29.

- Longstreth, Richard W. The American Department Store Transformed, 1920-1960. New Haven [Conn.]: Yale University Press, c2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/427757209.

- Lord & Taylor Collection. FIT Special Collections and College Archives. New York: Fashion Institute of Technology.

- McCulluch-Williams, Martha. “Emancipation from the Dressmaker: Clothes Which Fit Now Sold by Mail, to the Relief of Womankind,” Good Housekeeping, vol. 47, issue 4 (September 1908): 316-319. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1715348131?accountid=27253.

- Mears, Patricia. “Jessie Franklin Turner: American Fashion and ‘Exotic’ Textile Inspiration,” Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 1998. Accessed December 18, 2018. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1190&context=tsaconf.

- Morgan, Angela. “Milady Goes Shopping,” Red Book Magazine, December 1923, vol 42, issue 2: 22-23. Accessed December 1, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1846806462?accountid=27253.

- Moore, Margaret. End of the Road for Ladies’ Mile? New York, NY: Drive to Protect the Ladies’ Mile District, 1986. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/16661688.

- Mooring, Mark. “Mark Mooring Collection, 1923-1959,” FIT Special Collections and College Archives. New York: Fashion Institute of Technology, 1923—

- Museum at FIT, “Traina-Norell.” Museum of FIT, Fashion Institute of Technology. Accessed December 18, 2018. http://fashionmuseum.fitnyc.edu/view/people/asitem/items$0040:544/0?t:state:flow=1ac446f9-d8a5-4673-bcb5-6b50c2c6b7da.

- Neimark, Ira. The Rise of Fashion and Lessons Learned at Bergdorf Goodman. New York: Fairchild Books, c2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1053944167.

- The New York Times. “Home Fashions for America,” The New York Times, December 8, 1912. Accessed December 12, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/97335677?accountid=27253.

- _________. “Mark Mooring, 71, Fashion Designer,” The New York Times, January 13, 1971. Accessed November 20, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/1971/01/13/archives/markmooring-i-fashion-designer-exaide-at-bergdors-dies-won-critics.html?_r=0.

- _________. Muriel King Dies; Designed Dresses for Films in 30’s. The New York Times, March 23, 1977. Accessed December 18, 2018. http://www.nytimes.com/1977/03/23/archives/muriel-king-dies-designed-dresses-for-films-in-30s.html.

- _________. The New York Times’s Prize Contest Winners in American Fashion, The New York Times, February 23, 1913. Accessed December 12, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/97380312?accountid=27253.

- O’Hagan, Anne. “A Lesson in Buying,” Good Housekeeping, vol. 54, issue 1, January 1912: 124a, 125a, 126a. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1934095143?accountid=27253.

- Porter, Edwin S. The Kleptomaniac [videorecording]. Classic Video Streams, 1905. Accessed December 12, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ZZFyp1luC8.

- Potvin, John, ed. The Places and Spaces of Fashion: 1800-2007. New York: Routledge, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/826856012.

- Rantisi Norma. “How New York Stole Modern Fashion.” In Fashion’s World Cities, edited by Christopher Breward and David Gilbert, 109–122. Oxford: Berg, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/255478583.

- Robertson, Nancy MacDonell. “Miss Jazz Age: The Fashion Criticism of Lois Long, 1925-1969.” Diss., Fashion Institute of Technology, 2017. Accessed December 11, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1964275246?accountid=27253.

- Starr, Frederick. “The Secret Back of Fifth Avenue,” Ladies’ Home Journal, October 1913: 30. Accessed December 8, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/wma/docview/1715467799/fulltext/A8616D5AE6A84D5APQ/1?accountid=27253.

- Talmey, Allene. “No Progress, No Fun.” Vogue, February 1, 1946: 158-158, 159, 192, 194, 196, 198. Accessed November 28, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/879246002?accountid=27253.

- Thurman, Judith. “Ask Betty,” The New Yorker, November 12, 2012. Accessed December 16, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/11/12/ask-betty.

- Tortora, Phyllis G. “History and Development of Fashion.” In Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: Global Perspectives, edited by Joanne B. Eicher and Phyllis G. Tortora, 159–170. Oxford: Berg, 2010. Accessed September 27, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch10020a.

- Vogue. “Fashion: Frocks and Gowns Made to Order,” Vogue, April 15, 1915: 60-60, 61. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/911855275?accountid=27253.

- Welters, Linda, and Patricia A. Cunningham. “The Americanization of Fashion.” In Twentieth-Century American Fashion, edited by Linda Welters and Patricia A. Cunningham, 1–8. Dress, Body, Culture. Oxford: Berg, 2008. Accessed September 27, 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/9781847882837/TCAF0005.

- Whitaker, John. Service and Style: How the American Department Store Fashioned the Middle

Class. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865093390. - Women’s Wear Daily. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest, 1910-2017.

- _________. “Frilliest Frocks Since 1912, Says Miss Steinmetz,” Women’s Wear, March 18, 1920. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1666075333?accountid=27253.

- _________. “Many Opinions of Interest Brought Back From Paris Openings by Rochambeau Passengers: Velvet in Favor With French. (1919, Sep 02). Women’s Wear, September 2, 1919, 19, 3. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1665883774?accountid=27253.

- _________.Miss Steinmetz Leaves Stein & Blaine,” Women’s Wear Daily, September 19, 1932: 1, Accessed December 18.2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1653489037?accountid=27253.

- _________.”Museum Cloths Rich in Practical Ideas,” Women’s Wear, December 13, 1918: 6. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1666101118?accountid=27253.

- _________.Peplum Silhouette and Ombre Treatments of Color Mark Costumes Worn in “Polly,” Women’s Wear Daily, 38, 3, January 9, 1929. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1699908564?accountid=27253.

- Zachary, Cassidy. “Ethel Traphagen: American Fashion Pioneer,” Diss., Fashion Institute of Technology, 2013. Accessed December 18, 2018. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/1687190108?accountid=27253.