One of the earliest forms of clothing. Made from goat or sheep’s wool and meant to be worn around the waist like a skirt, it is recognizable by its fringe detailing.

The Details

Daniel Delis Hill in The History of World Costume and Fashion (2011) introduces the term kaunakes when describing early civilizations in Mesopotamia:

“Among the first beasts domesticated by Neolithic settlers of Mesopotamia were sheep and goats. The wool from these animals provided the early Sumerians with the raw materials for their clothing. The most rudimentary garments of the earliest Sumerians were hardly more than variations of the animal pelts first worn by Paleolithic man over 30,000 years earlier. Hanks of sheep or goal wool, probably still attached to a tanned hide, were stitched or knotted together in horizontal bands to fashion wrap skirts called kaunakes. Lengths of the kaunakes varied and included waist-to-knee or mid-calf styles for men and breast-to-ankle versions for women. The fleecy surface of the traditional kaunakes became imbued with ritual symbolism and continued to be worn for hundreds of years, even as the manufacture of woven materials became more prevalent. Sculptures of the fourth millennium BCE depict typical Sumerian kaunakes that feature stylized representations of the shaggy petals of wool, which by this time were applied to panels of woven wool or linen, a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.” (19)

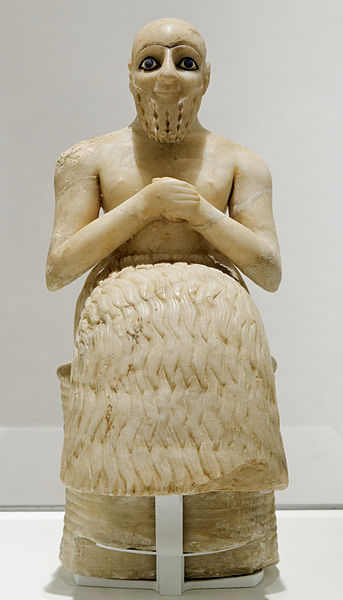

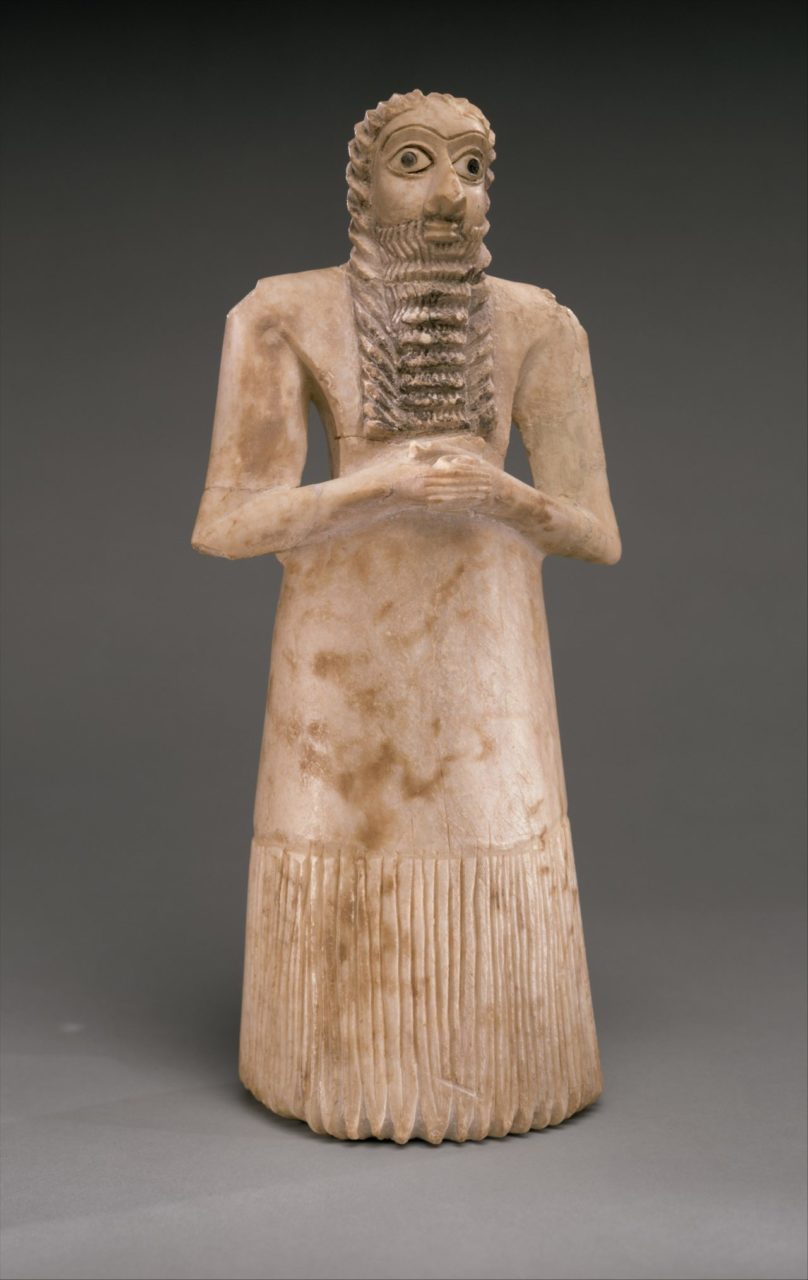

It is believed that the style of kaunakes varied and evolved over time, as we can see in figures 1 & 2. Figure 3 shows different variations of the garment when worn by women. To prove this point, Kemper in the book Costume (1977) further explains the term:

“The earliest male costume from the ancient Near East was a compromise, combining the authority of fur with the convenience of cloth. The garment, called the kaunakes, was the world’s first example of fake fur. It was made by threading tufts of wool or loosely rolled yarn through a coarsely woven cloth panel. The tufts were inserted in neat rows and brushed or combed toward the hem of the garment. The result was a long, shaggy kilt that must have looked a great deal like a flokati rug. In some of the early examples, a large tuft like a tail was retained at the rear. Eventually Sumerian males were eased into plain, heavy woolen cloth with tufts retained only as a decorative fringe.” (34)

François Boucher in 20,000 Years of Fashion (1987) elaborates:

“In the oldest representations of humans, which date from the third millennium, the skins of various wild animals, formerly worn over the shoulders, were now draped round the hips like a skirt; these garments were made from long-haired skins, particularly sheepskins whose texture is represented by hatched patterns, from 2900 to about 2500 BC in Mesopotamia (Sumer and Akkad). Then, towards 2500 BC, in Telloh, skins sewn together are represented by bands of straight and wavy stripes on representations of the skirts and cloaks worn throughout Sumer. The fashioning of these skins made it possible to adapt them into garments such as gowns.

These skins were used in skirts and cloaks from about 2885 BC to form complete garments; then, towards 2500 BC, they were made with sleeves, which may have been simple unsewn flaps of skin folded over the arm. Vertical fringes along the foot of garments, perhaps made of leather thongs, seem to date from the beginning of the third millennium.

During the third and second millennia the term kaunakes was still applied to this garment, and thus referred not to a material but to a form. From 2700 BC at the earliest and until about the fourth century BC, the hides originally used for these skirts and gowns were replaced by kaunakes cloth, a textile imitating goat-skin, while short capes were still made of skin or hide.” (34)

Figure 4 seems to depict a garment now made of kaunakes cloth rather than out of skin or hide. Phyllis Tortora discusses the various evidence we have for early Sumerian dress in “Ancient World: History of Dress”:

“One of the chief products of Mesopotamia, wool, was used not only domestically but was also exported. Although flax was available, it was clearly less important than wool. The importance of sheep to clothing and the economy is reflected in representations of dress. Sumerian devotional or votive figures often depict men or women wearing skirts that appear to be made from sheepskin with the fleece still attached. When the length of material was sufficient, it was thrown up and over the left shoulder and the right shoulder was left bare.

Other figures seem to be wearing fabrics with tufts of wool attached, which were made to simulate sheepskin. The Greek word kaunakes has been applied to both sheepskin and woven garments of this type.

Additional evidence of the importance of wool fabric comes from archaeology. An excavation of the tomb of a queen from Ur (c. 2600 B.C.E.) included fragments of bright red wool fabric thought to be from the queen’s garments. Evidence for costume in this region comes from depictions of humans on engraved seals, devotional, or votive statuettes of worshipers, a few wall paintings, and statues and relief carvings of military and political leaders.” (51-59)

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Statue of Ebih-Il, 2400 BC. Gypsum, lapis lazuli and shell; 52.50 x 20.60 x 30 cm. Paris: Musée de Louvre, AO 17551. Source: Musée de Louvre

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown. Gypsum Statue of Shaven Man, 2500BC, Early Dynastic III. Gypsum; 29.3 x 13.4 x 12 cm. London: British Museum, 134300. Source: British Museum

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown. Statue of the Goddess Narundi, 2100 BC. Paris: Musée de Louvre. Source: Musée de Louvre

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Standing Male Worshiper, 2900–2600 BC. Gypsum alabaster, shell, black limestone, bitumen; 29.5 x 12.9 x 10 cm. New York: Th Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (Sumerian). Early Dynastic II Votive Statue of Eannatum, Prince of Lagash, 2600-2340 BC. Alabaster, lapis lazuli, mother of pearl inlays, and modern bitumin inlays; (12 x 4-1/2 x 4 in). Houston: The Menil Collection. Source: Saatchi Gallery

Its Afterlife

Fig. 6 - Pedro Lourenco. Ready-to-Wear, Fall 2013. Source: Vogue

Fig. 7 - Dsquared2. Ready-To-Wear Collection, Spring/Summer 2014. Source: Vogue

References:

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. Expanded ed. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1987. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/979316852.

- Guisepi, Robert A. “Sumerian Clothing and Dress.” Accessed August 10, 2018. http://history-world.org/sumeria,%20dress.htm.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/768100950.

- “Kaunakes.” Wikipedia, December 27, 2017. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Kaunakes&oldid=817330722.

- Kemper, Rachel H. Costume. World of Culture. New York: Newsweek Books, 1977. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/993506398.

- Tortora, Phyllis. “Ancient World: History of Dress.” Encyclopedia of Clothing and Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, vol. 1, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2005, pp. 51-59. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2540/apps/doc/CX3427500031/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=756f0648. Accessed 10 Aug. 2018.