When the spirit of the ’60s brought new relevance to the ’20s silhouette, Norman Norell was at the vanguard of the revival. Indeed, at a time when other designers looked toward the future, Norell looked to the past.

Norman Norell’s career as a fashion designer was largely defined in the 1920s and the 1960s. In 1920, while studying costume design at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, Norman David Levinson invented the surname Norell (Banks & De La Chapelle 98). He then began amassing costume design credits for both the theater and silent films, including A Sainted Devil (1921) and Zaza (1923). Also, Norell took joy in making costumes for vaudeville and burlesque stars, as well as for the Ziegfeld Follies and performers at the Cotton Club (Banks & De La Chapelle 104).

Then, in 1924, Norell left costuming to work in the fashion industry. Soon after, he began working for the fashion entrepreneur Hattie Carnegie (Fig. 2). It was there that Norell gained an understanding of Parisian couture, as he studied and even reassembled garments by couturiers including Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel, Jean Patou, and Madeleine Vionnet (Banks & De La Chapelle 108).

Yet it was not until 1941 that Norell truly “came to fame” as a designer himself, when he began a collaboration with Anthony Traina (Banks & De La Chapelle 109). His first collection with Traina is regarded as a pivotal moment in American fashion, departing from reliance on European design. After Traina’s retirement in 1959, Norell formed Norman Norell, Inc. His debut as an independent designer came in 1960.

Norell referenced 1920s styles at various points throughout his career. In a move described as “courageous” and “radical,” he introduced “very low waists” and “very short skirts” for Traina-Norell in December of 1957 (Women’s Wear Daily 4). Yet Women’s Wear Daily wrote that “the collection is said to have the look of 1958 and not that of the 1920s” (Women’s Wear Daily 4). In December 1959, for his very last collection for Traina-Norell, Norell again showed a collection featuring lowered waists, chemise silhouettes, and suits that he described as “in the Chanel manner” (The New York Times 1959).

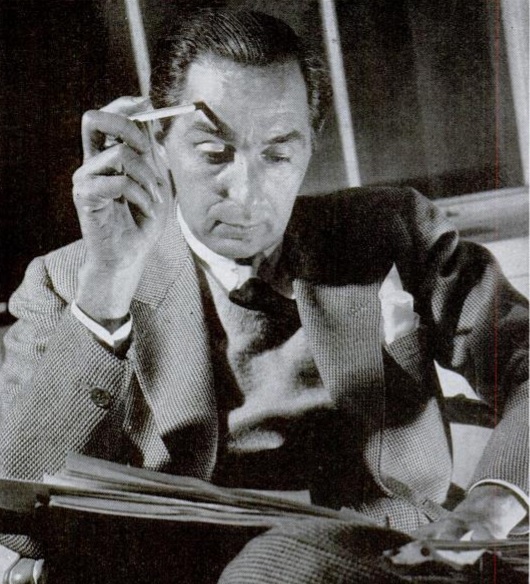

Fig. 1 - Photogapher unknown. Norman Norell, May 1944. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Attributed to Norman Norell (American, 1900-1972). Ensemble, 1928. Silk, metal. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.58.34.9a, b. Gift of Mrs. John Chambers Hughes, 1958. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

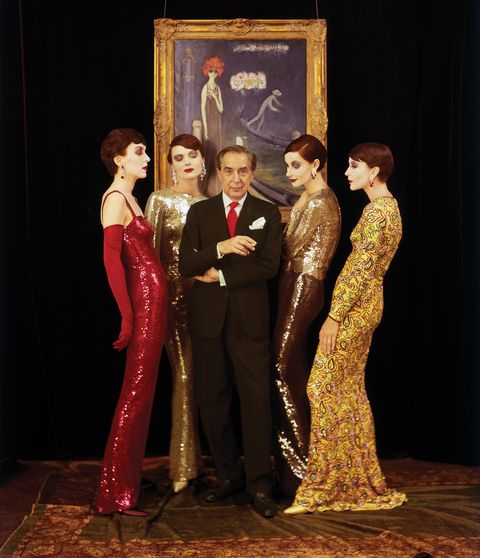

Fig. 3 - Milton H. Greene (American, 1922-1985). Norman Norell and models, 1960. Photograph. Source: Joshua Greene

Norell’s first collection in the 1960s was even more directly inspired by the 1920s, especially when it came to styling. His muse for his 1960 collection was a 1921 portrait he owned of the Marchesa Luisa Casati by Kees van Dongen (Fig. 3) (Donovan). Referencing the painting, he had his models made up with burnt-cork black eyes and dark red lips (Donovan). Fortuitously, at around the same time, a trip to Paris inspired one of Norell’s models, Yvonne Presser, to crop her hair (Donovan). Other models received a “drastic shingle” cut by the hairstylist Eddie Senz, and some were styled with deep cloche hats (Banks and De La Chapelle). The fashion designs themselves were rather modern and “avant-garde,” many featuring culottes or pants at a time when skirts were the norm. Carrie Donovan wrote for The New York Times, “The whole effect was one of boyish, perhaps, but terrific elegance” (Donovan). The authors of Norell: Master of American Fashion wrote that the timing for this collection was “perfect” because “the advent of the ’60s brought with it a new, more avant-garde experimentation” (Banks and De La Chapelle).

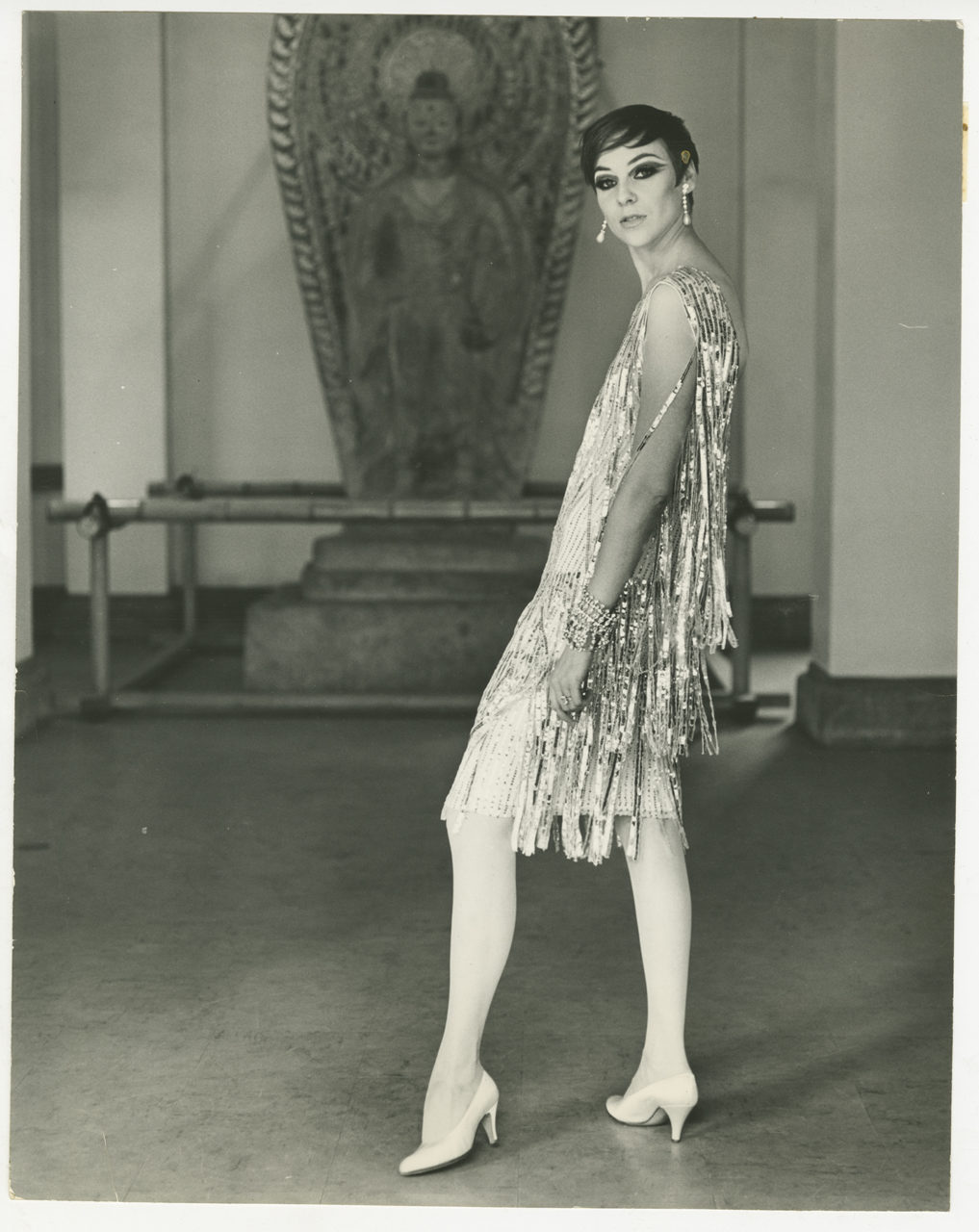

Norell’s autumn/winter 1965-1966 collection was his most obvious revival of the 1920s, in terms of both fashion design and styling. Many of these designs were practically copies of 1920s frocks by the couturiers Chanel and Edward Molyneux. Models furthered his nostalgic vision by walking the runway with short hair, charcoal eyes, false lashes, red lips, and rouged knees (Vogue 1965, 150-153). A pairing of garments in The Roaring Twenties and The Swinging Sixties demonstrates exactly this. The silhouette of a black wool crepe Norell dress with a high, round neckline and two tiers of long fringe hanging from the shoulder and the waist (Fig. 4) is the spitting image of a circa 1926-1927 sequined evening dress by Molyneux (Fig. 5). The Costume Institute possesses a very similar Molyneux of the same date, but in a golden hue (Fig. 6). It is nearly identical to the fringed sequin dress photographed at Norell’s 1965 showing in Japan (Fig. 7).

Fig. 4 - Norman Norell (American, 1900-1972). Evening dress, ca. 1965. Wool crepe. New York: Museum at FIT, 70.43.21. Gift of Lauren Bacall. Source: Museum at FIT

Fig. 5 - Edward Molyneux (British, 1891-1974). Evening dress, 1926-1927. Chiffon, sequins, and satin lined organza. New York: Museum at FIT, 74.25.1. Gift of Phyllis Hulburd. Source: Museum at FIT

Fig. 6 - Edward Molyneux (British, 1891-1974). Evening dress, 1926–27. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.42.33.3. Gift of Mrs. Adam Gimbel, 1942. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

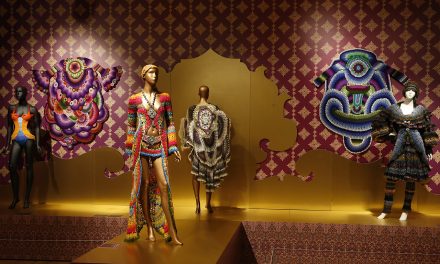

The catalog for the 2020 Costume Institute exhibition “About Time: Fashion and Duration” also highlighted the 1920s inspiration behind this collection (Fig. 8). When displayed next to each other, it’s clear that two of Norell’s designs drew direct inspiration from 1920s Chanel. One sequined dress mirrored a 1925 Chanel in its fabric, tired skirt, and floral corsage. Another revived the loose-fitting bodice, box-pleated skirt, and belt of a 1927 two-piece Chanel frock. However, Norell’s designs were not exactly identical to Chanel’s. The publication describes how Norell subtly updated the silhouette for the 1960s, primarily by shortening the skirt and the sleeves, thereby revealing more skin (Bolton et al.).

The reception to Norell’s attempt to revive 1920s styles were mixed. In September 1965, one New York Times reporter praised Norell’s collection for tapping into a craze for “flapper” dresses that “the young crowd first discovered … in old trunks and in thrift shops” (Peterson). Indeed, there was a fashionable trend of young ladies coveting vintage frocks. Vogue offered praise for Norell’s low-waisted proportions: “Modern to the bone, without a flicker of nostalgia, his clothes at the same time bring back the best of an era of great elegance” (Vogue, 1966, 64-67). However, some fashion journalists were clearly reluctant to go back in time. The following year, another New York Times reporter wrote:

“Norman Norell, the Seventh Avenue designer who disappointed many of his fans last summer with a fall and winter collection that smacked of Chanel in the 1920s, was back in the ’60s again Monday night …” (Curtis).

While Norell did not personally explain why he connected the fashions of the two decades, it is no coincidence that his 1920s revival reached its apex in the 1960s. He personally felt the 1920s was a time of great fashion innovation, and told Life magazine it was the period “to which women owe short hair, fake jewelry, and little black dresses” (Life 1960, 22-26). He specifically gave credit to Chanel for having “started everything [in fashion] that’s current today” (Bolton et al.). What he did not explain, perhaps because it was too soon to say, were all the historic similarities between the ’20s and ’60s. Both the ’20s and ’60s can be described as revolutionary decades, arriving on waves of feminism, social progress, technology, and culture. All of these amounted to new definitions of the “modern” woman, who embodied modernity through short hemlines and youthful figures. Eventually, other 1960s designers and couturiers caught on to the renewed relevance of 1920s styles, but Norell was officially credited by Life with having anticipated the trend (Life 1961, 54-57).

Fig. 7 - Photographer unknown. Silver Sequined Fringe dress, September 1965. Photographic print; (9" x 11.5" in). New York: The New School Archives and Special Collections, Kellen Design Archives, KA0035_000051. Source: The New School Archives

Fig. 8 - Dolly Faibyshev. About Time: Fashion and Duration, 2020. Photograph. Source: New York Times

References:

- “American Collections for Spring: Norell Teams a Lowered Waistline With Dirndl Skirt.” The New York Times, Dec 16, 1959.

- Banks, Jeffrey, and Doria De La Chapelle. Norell: Master of American Fashion. New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083136075

- “Beauty Bulletin: The Face American Fashion Designers Are Seeing With Their Clothes.” Vogue, Sept. 15, 1965, 150-153.

- Bolton, Andrew, Jan Glier Reeder, Jessica Regan, and Amanda Garfinkel. About Time: Fashion and Duration. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1164335590

- Curtis, Charlotte, “Norell Reassures Faithful Fans.” The New York Times, Jan 05, 1966.

- Donovan, Carrie, “American Collections: Norell Decrees Pants Are the Fashion.” The New York Times, Jun 22, 1960.

- “Fashion: The Norell Idea.” Vogue, Feb 15, 1966, 64-67.

- “Norell Styles Raise Ruckus All Their Own.” Life, September 26, 1960, 22-26. https://books.google.com/books?id=H08EAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=Life%2C%20September%2026%201960&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Peterson, Patricia. “The Flapper Frugs.” The New York Times, Sep 18, 1965.

- “The Paris Rage — Spring Styles From a Crazy Age.” Life, March 3, 1961, 54-57. https://books.google.com/books?id=wUUEAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PP1&dq=Life%2C%20March%203%2C%201961&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false

- “Traina-Norell’s Spring Silhouette: Very Low Waist, Very Short Skirt: Short Evening Dresses.” Women’s Wear Daily, Dec 05, 1957, 4.