The image of the Virgin of Guadalupe is one that is intertwined with Latinx heritage and her identifiable symbols have been adopted as an expression of individuality, identity, and pride.

Every December 12th brings a big celebration to the Latinx community—Aztec dancers in their colorful regalia with their chachayotes rattling on their ankles as they step to the drum; mariachis playing and belting out songs of praise; folklorico dancers from various regions dancing along to the mariachi’s music; señoras pouring atole or champurrado into styrofoam cups and selling food and merchandise. It is a hotbed of activity that begins in the early morning and continues until mid-day. Swarms of people crowd around their local church dedicated to La Reina de las Americas: La Virgen de Guadalupe (Fig. 1).

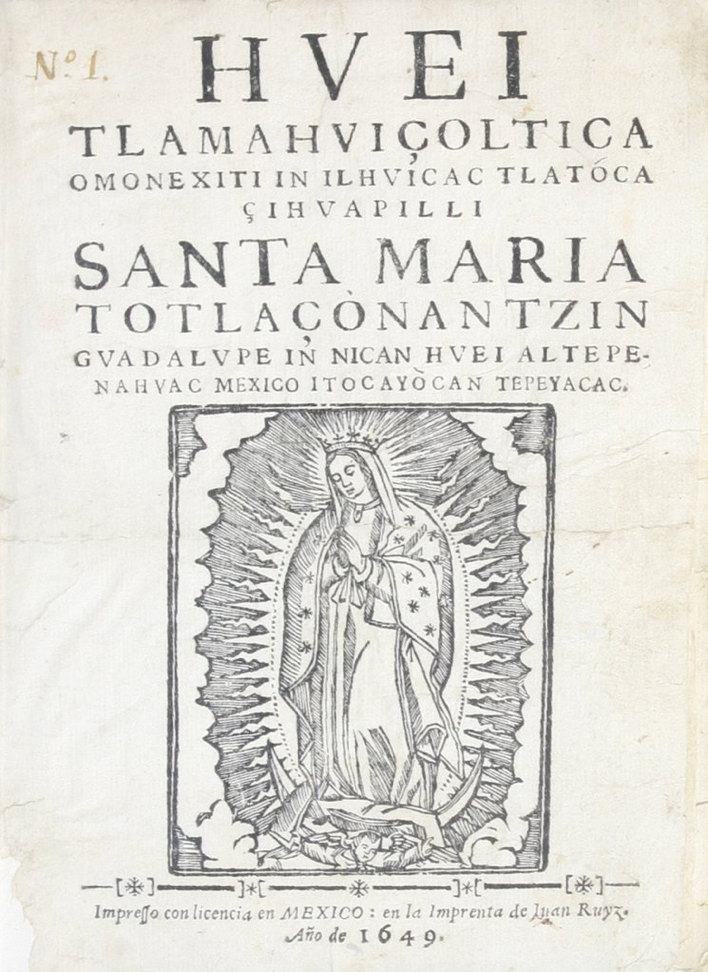

The Virgin of Guadalupe’s image is promoted everywhere, from calendars, candles, and t-shirts to five-foot tall statues that recreate her apparition to Juan Diego. That famous moment is relayed in the Nican Mopohua, the earliest account of Guadalupe’s appearance. The Nican Mopohua uses her image on the title page to signify the importance of the story. The manuscript, written in Nahuatl in 1649 (Fig. 2), details Guadalupe appearing to an indigenous man named Juan Diego on Tepeyac hill in December 1531. She appears to him four times with instructions to build a church dedicated to her, each time he was ignored by the local clergymen until she miraculously imprinted her image on his tilma (Fig. 1) with dozens of vibrant out-of-season roses. Fueled with renewed passion at the sight of the miracle, the bishop ordered a cathedral to be built in her honor at the exact site she appeared at, which is now the Basilica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Mexico City.

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Image of our Lady of Guadalupe on the tilma of Juan Diego, December 1531. Tilma. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 2 - Luis Lasso de la Vega (Mexican). Hvei tlamahviçoltica omonexiti in ilhvicac tlatocacihvapilli Santa Maria totlaçonantzin Gvadalvpe / Great Miracle of the Apparition of the Queen of Heaven, Saint Mary Our Beloved Mother of Guadalupe, 1649. Source: World Digital Library

Figure 1 is the Virgin of Guadalupe’s appearance in the purest form: a blue-green mantle covered in stars, a dress with floral embroidery and a black sash tied high at the waist. Her dark hair peeks through as her head is bowed and her hands are in prayer. Only one foot pokes out on top of the upside-down crescent moon with an angel lifting her up as golden rays shine behind her to create a mandorla. This classic image of Guadalupe is constantly reworked by artists, politicians, revolutionaries, and even devotees because

“many believe that they communicate directly with her in an intense and daily interaction.” (Hall 3)

Historically, religious icons have always lent inspiration to fashion, whether that is fashioning one’s identity or one’s physical appearance. The popular devotion to the Virgen of Guadalupe is no exception. Let’s begin by analyzing the basic aspects of her image: roses, color-palette, and mantle.

ICONOGRAPHY OF THE VIRGIN

The Nican Mopohua details the miracle of the roses in lines 128-131:

“And when he reached the top, he was astonished by all of them, blooming, open, flowers of every kind, lovely and beautiful, when it still was not their season, / because really that was the season in which the frost was very harsh. / They were giving off an extremely soft fragrance; like precious pearls, as if filled with the dew of the night. / Then he began to cut them, he gathered them all, he put them in the hollow of his tilma.”

Even though there are no roses in the original image, the Castile Rose (Fig. 3) has been synonymous with Guadalupe’s image “because they were material proof of her apparition,” (Herrera-Sobek, Latorre, Lopez 82). In addition to being proof of her apparition, the roses symbolized classic themes of beauty and love (Goldman 131). Figure 4 is an 18th-century representation of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Her basic image is still present, with an addition of a crown, but now she is surrounded by lush, blossoming flowers that were painted and inlaid with mother of pearl. Images that correlate her image with flowers provide her with a sense of agency because those flowers were an extension of her presence, one not interceded by God or any other male deity.

Guadalupe’s color palette consists primarily of green-blue, gold, red, black, and brown. In figure 1, the colors are placed in order to work in cohesion, not separately: the green-blue mantle brings the viewer’s eyes into focus and allow them to look at her face; the lines flow down along her embroidered tunic to the black sash tied at her waist. The angel’s color pattern mimics Guadalupe’s with red, blue and gold which reinforces the color placement on her person. In Santa Barraza’s Nepantla (Fig. 5), the palette of the tilma Guadalupe is reinforced throughout Barraza’s composition. At the center of the figure’s back, Guadalupe is cloaked in her blue mantle and red tunic with complementary embroidered flowers in blues, yellows, and reds. Mina Garcia Soormally notes in “The Image of a Miracle: The Virgin of Guadalupe and the Context of the Apparitions”:

“Long before the arrival of the Spanish conquering forces, the hill of Tepeyac had already been the site of an ancient pilgrimage tradition centered around a pagan deity… named Tonantzin, venerated as the earth and fertility goddess, and also known as “Our Lady Mother.” (Soormally 178)

Greens and blues are universally known to be earth tones associated with life-giving forces found in nature. In figure 5, the outstretching agave, nopal, and lilies, places Guadalupe in the same context as Tonantzin, both maternal deities who protect and watch over devotees. The colors emphasize her position: Guadalupe’s blue mantle reflects the blue sky and even the shape is reminiscent of the blue mountains in the background, while the red tunic is representative of the orange-red ground. A force that is seen on a piece of clothing and within nature itself.

The star-covered mantle is annother of the primary focal points of Guadalupe’s image (Fig. 1) because it is the second largest article of clothing on her person next to her tunic. As mentioned previously, the color palette is synonymous with nature as the eye automatically goes from one garment to next which is replicated as the star-covered sky and the vegetation on the ground. The original tilma image of Guadalupe falls in line with the tradition of women wearing a rebozo, a woven mantle that is primarily worn over the head. However, the rebozo has many uses: carrying items and children, a blanket, and even replaces an engagement ring in some areas of Mexico (Giordano). Rebozos have a dual nature as a tool but also as an extension of the wearer. Intricate techniques and luxurious materials would be used for special rebozos or women of the leisure classes.

Fig. 3 - Photographer unknown. Rosa x damascene (also known as the Damask rose or the Castile Rose), 2016. Source: ScienceDirect

Fig. 4 - Agustin del Pino. Virgin of Guadalupe, 18th century. Mother of pearl, oil paint, wood panels, inlay; 70 x 50 cm. Mexico City: Museo Franz Mayer. Source: ARTSTOR

Fig. 5 - Santa Barraza (American, born 1951). Nepantla, 1995. Oil on canvas; (39 x 48 in). Source: Pinterest

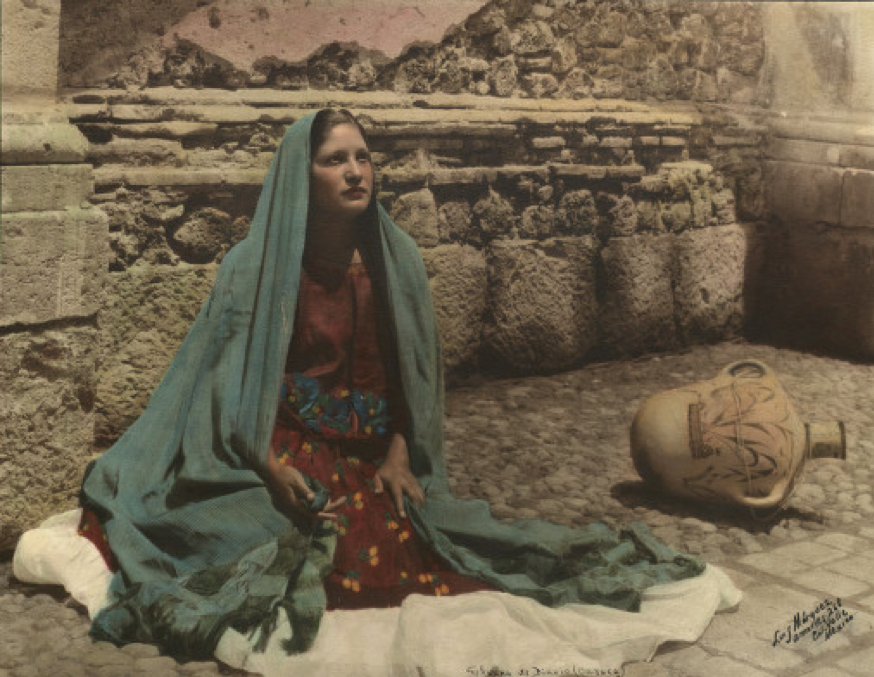

Fig. 6 - Luis Marquez (Mexican). Tehuana de Diario, 1937. Hand colored photograph; (13 1/4 x 10 3/8 in). Houston: University of Houston Libraries Special Collection. Source: Wikipedia

Figure 6 shows a photograph of a woman in traditional tehuana attire sitting against a stone wall. She faces the hot sun while a tipped over jar is at her side. While the colors are coincidentally similar to Guadalupe, this photograph provides an excellent example of how large rebozos are. In the tilma image (Fig. 1), Guadalupe’s star-covered mantle enshrouds her body in a protective way against the bright rays shining behind her, similar to how the woman’s rebozo is shielding her body from the sun. But for Guadalupe, her mantle implies her majestic nature by the stars reflecting off of the rays as if she is wearing a coronation gown: her mantle is her crown as reina of the heavens.

REFASHIONING HERSELF

The word “fashion” is primarily used as how one makes up their appearance: clothes, jewelry, tattoos, shoes, and hairstyles. However, I am using this term to discuss how one fashions themselves in Guadalupe’s image to express their identity. Linda B. Hall’s “Images of Women and Power” cites David Freeberg’s insight, “that sometimes images are treated as if they were living, and, moreover, the images themselves may weep, bleed, sweat, and otherwise seem to be animate,” (Hall 3). By the devotee putting themselves in the same position, they become her as if she was a living person. That is why I am labeling Guadalupe as a “fashion icon” because her appearance influences a worldwide devotion that employs her aesthetics in their own personal way.

Continuing off of Hall’s comment, most artists center on the appearance of Guadalupe and add agency to her. Alma Lopez, the famous Chicana artist of Our Lady (1999), stated:

“We grew up with the Virgen in our homes and everywhere else in our culture. I, however, have always been curious about all the clothes that she wears, these big heavy garments that prevent her from moving freely—she cannot walk because they are all wrapped around her.” (Herrera-Sobek, Latorre, Lopez 82)

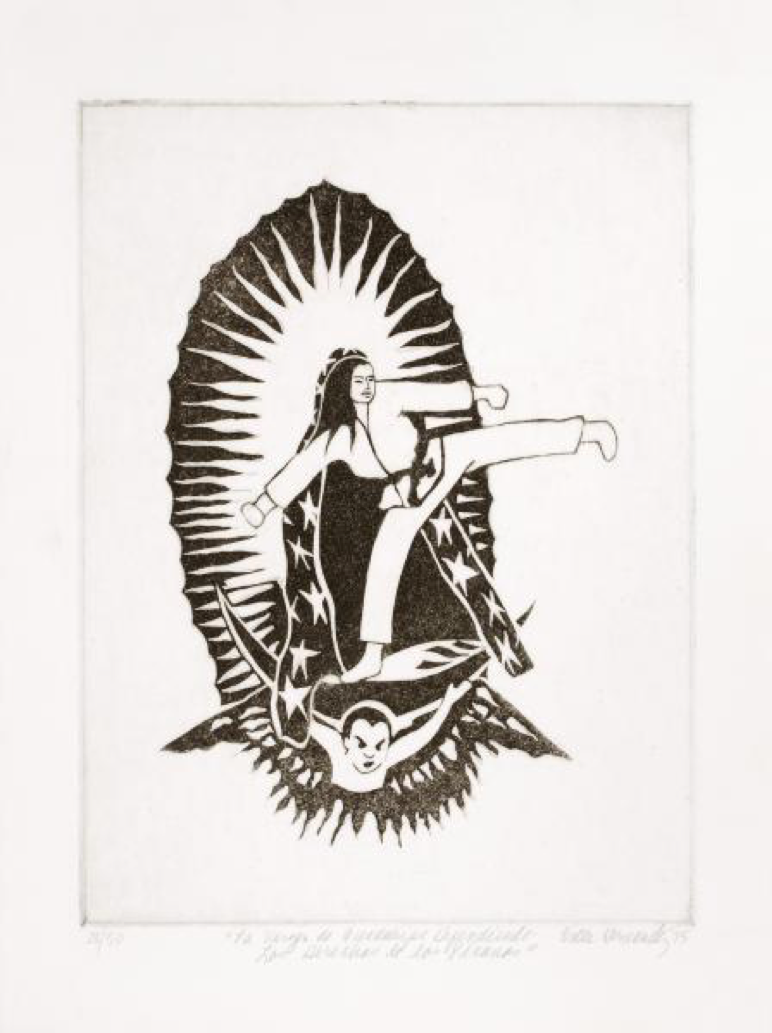

Fig. 7 - Ester Hernández. La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de los Xicanos, 1975. Etching and aquatint on paper; (15 x 11 in). Washington D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Museum purchase through the Frank K. Ribelin Endowment. Source: SAAM

It is this limitation that often captures artists’ imaginations and prompts them to “liberate” her. Esther Hernández’s La Virgen de Guadalupe Defendiendo los Derechos de los Xicanos (Fig. 7) echoes Lopez’s concern about Guadalupe not being able to move freely. The print consists of the classic elements of Guadalupe: rays, star-covered mantle, upside-down moon, and an angel holding her up. However, Guadalupe’s physical body is in the middle of doing a kick while wearing a gi, a karate uniform. Her mantle is in place as if she was just there for a brief moment and moved herself into a kicking position. This image has more agency and a physicality than the original tilma image. Here, she is physically using her body to protect those who need her protection.

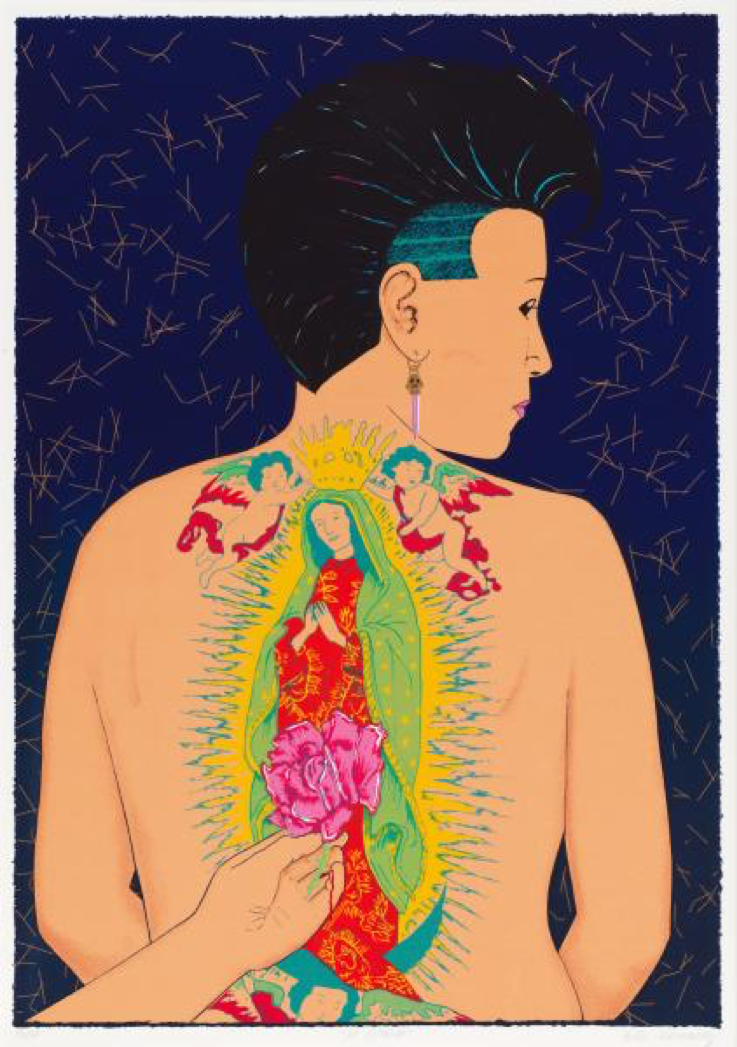

Fig. 8 - Ester Hernández (American). La Ofrenda,, 1988-1989. Screenprint on paper. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of the Wight Art Gallery, University of California, Los Angeles, 1991.65.3. Source: SAAM

For other artists, wearing her image and using her aesthetics is a form of expressing a need for protection and veneration. Esther Hernández’s La Ofrenda (Fig. 8) depicts a colorful tattoo of the Virgen on a person’s back. The bottom left shows another person’s hand holding a flower out to the image as if they are placing it on an altar. Here, the tattoo is an act of reverence and a sacred site to whomever calls upon her image. Delia Cosentino, an associate professor at DePaul University, commented in Ximena N. Larkin’s article, “How La Virgen de Guadalupe Became an Icon”:

“Because of her religious foundations, I don’t think you have to have an association… to recognize her power… [because] the idea that you could embrace her and she could serve whatever needs you have, regardless of your ethnic or religious identity.” (Larkin).

La Ofrenda is a demonstration of the power of Guadalupe’s image and the tattoo, a permanent form of art on the body, transcends the power of an altar in a church. The Virgen seen in the tattoo becomes a placeholder for a site to honor others—a mirror where one can see themselves and others in her, which is a driving force for the popularizing of her image. Devotees feel closer to themselves through her.

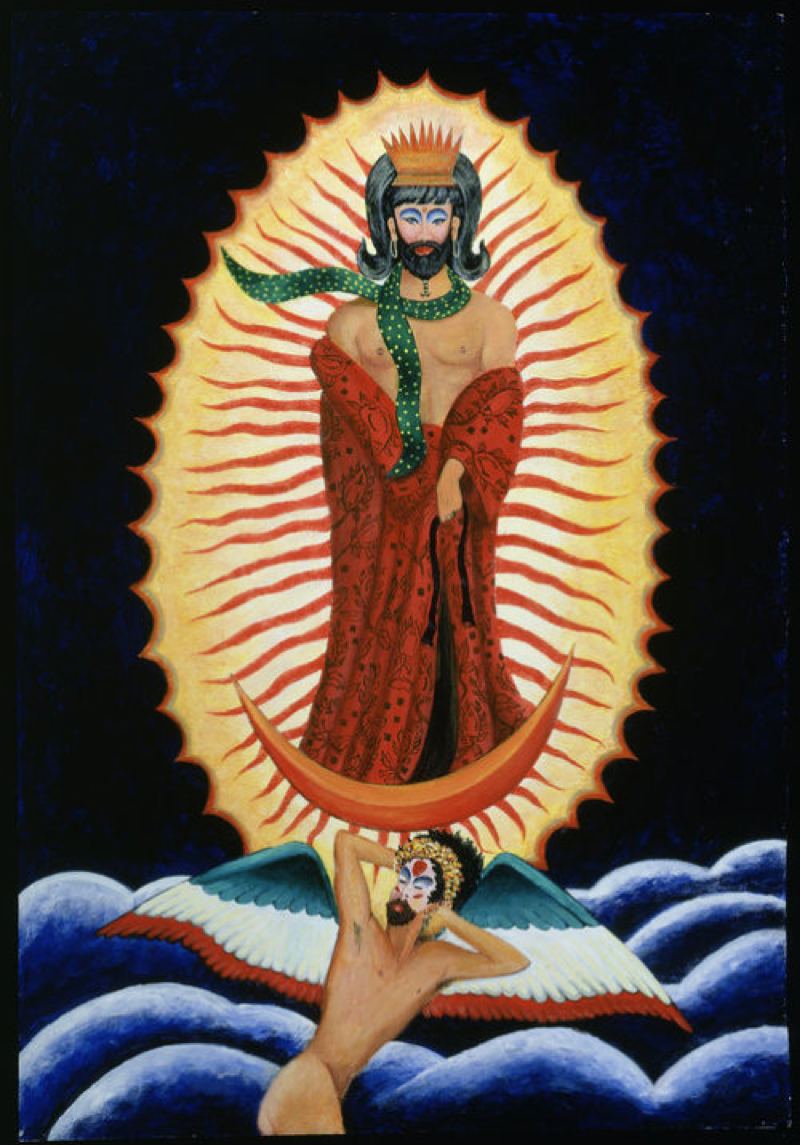

The Virgin as a “fashion icon” can be seen in her appearance in clothing and tattooing as we’ve seen, but also more specifically in how people see themselves and project their identity to society. Figure 9 demonstrates how the Guadalupe image can be refashioned to reflect specific experiences. Guadalupe is a glamorous, bearded drag queen with a high bouffant, blue eyeshadow, shimmering jewels, and a brilliant crown. A star-studded scarf and embroidered robe are hanging off their body seductively. An angel lounges under the upside-down crescent moon amongst a cloudy sky. The artist’s depiction is not done out of disrespect, but as a form of emulation—wanting to have the same power, energy, and glory as the Tepeyac Guadalupe. This Guadalupe reflects the majesty and pride within the LGBTQIA+ community. Guadalupe in this context is more about being seen and respected for who you are—the scarf flowing, the robe is hanging loosely on the body while the black sash is untied—unapologetically and free. Cosentino states,

“The fact that her image is often associated with the oppressed classes is a function of more modern times. Her ambiguous roots have allowed her to become a symbol for those people who don’t have a voice.” (Larkin)

Fig. 9 - Jim Ru. Virginia Guadalupe, 1990. Acrylic on board. Source: YouTube

The fashion choices within Virginia Guadalupe in comparison to the “classic” image (Fig. 1) is freer and more expressive of the individual. Tepeyac Guadalupe is indicative of the religious ideologies she stands for, “…chasteness and ideal femininity…the unselfish and suffering mother (McMahon 183). However, Virginia Guadalupe is evocative of the personal freedom of being their authentic self: crowning themselves as a reinx and being recognized as such in the same manner of Tepeyac Guadalupe being queen of heaven.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Her depiction on a tilma, a thick shawl worn mostly by indigenous communities, can be linked to one of the first instances of wearing Guadalupe as a form of reverence. The original source being an image imprinted onto material connects the fascination of Guadalupe’s physical appearance and fashion design. Dorie S. Goldman’s article “‘Down for La Raza’: Barrio Art T-Shirts, Chicano Pride, and Cultural Resistance” stated the Virgin of Guadalupe is a popular recurring theme in t-shirts she saw on youth because it provides meaning to the shirt since the icon is meaningful to the community (Goldman 125). Based on Goldman’s statement, Guadalupe is simply not a flat image meant for decoration, but a wearable shrine, an active site where two things are happening: the representation of one’s culture and a portable sacred site that holds the same significance as the original site in Tepeyac.

The appearance of Guadalupe on clothing can be seen as a pushback against the dominant Anglo (white) culture, as a way of demonstrating self-love and pride in one’s appearance. Wearing the Virgen’s image does not necessarily mean piety or abiding to Catholicism, but can also be a way to communicate pride and resistance to those (and a society) that would automatically dismiss the wearer. If she has permission to be unapologetically herself as La Reina de las Americas, then the wearer has permission to express themselves to the fullest extent.

References:

- Giordano, Mary. “Historical and Cultural Background of the Rebozo.” Madreluna, November 24. https://www.madreluna.com.au/blog/historical-and-cultural-background-of-the-rebozo

- Goldman, Dorie S. “’Down for La Raza’: Barrio Art T-Shirts, Chicano Pride, and Cultural Resistance.” Journal of Folklore Research 34, no. 2 (May-Aug 1997): 123-138. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3814844

- Hall, Linda B. “Images of Women and Power.” Pacific Historical Review 77, no. 1 (February 2008): 1-18. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/phr.2008.77.1.1

- Herrera-Sobek, María, Guisela M. Latorre, and Alma López. “Digital Art, Chicana Feminism, and Mexican Iconography: A Visual Narrative by Alma Lopez in Naples, Italy.” Chicana/Latina Studies 6, no. 2 (Spring 2007): 68-91. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23014501

- Larkin, Ximena N. “How La Virgen de Guadalupe Became an Icon.” VICE, December 12, 2017. https://www.vice.com/en/article/ywnwny/how-la-virgen-de-guadalupe-become-an-icon

- McMahon, Marci R. “Alma López’s “California Fashions Slaves”: Denaturalizing Domesticity, Labor, and Motherhood.” Chicana/Latina Studies 11, no. 1 (Fall 2011): 158-193. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23345303

- “Readings in Classical Nahuatl: Nican Mopohua: Here It Is Told,” University of California, San Diego. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://pages.ucsd.edu/~dkjordan/nahuatl/nican/NicanMopohua.html

- Soormally, Mina García. “The Image of a Miracle: The Virgin of Guadalupe and the Context of the Apparitions.” Chasqui 44, no. 2 (Noviembre 2015): 175-190. JSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24810768