Deciphering Jan Jansz Mostaert’s Portrait of an African Man reveals the presence of Black bodies within European court circles and hints at their position within them.

About the Portrait

Jan Jansz Mostaert is said to come from a famous noble family from the Haarlem region of the Netherlands. Haarlem is a city roughly 20 miles outside of Amsterdam in the northwest Netherlands. Mostaert’s career began with painting the housing of relics of the St. Bavo Groote Kerck in Haarlem and subsequently, his name is found within the records of the painters’ guild (Velde). As his body of work developed, so did his technique. Mostaert’s talents attracted notable commissions, inevitably fetching the eye of Margaret of Austria, Governor of the Netherlands. Records show his presence as a portrait painter within her court in addition to several mentions within the Haarlem archives between 1527 and 1554. As art historians Carl Van de Velde and James Snyder note in their biography of Mostaert:

“As a renowned court portrait painter, he enjoyed a steady patronage, and he is probably best known for his bust portraits with the sitter in three-quarter pose, resting his or her hands on a cushion before a low parapet against a sweeping landscape background.”

This artwork is a part of the holdings at the Rijksmuseum, located in Amsterdam. Their website describes the unique status of the work and what little is known about it:

“As far as the type goes, the painting belongs with a number of Flemish portraits of princes and noblemen from the early 16th century. It stands on its own in the group, being the only known portrait of a black individual from this period. Most contemporary depictions of black men in the role of Balthazar in the adoration of the Magi lack individualised features and are fairly stereotype. The traditional attribution to Jan Mostaert is confirmed by the similarities in style and technique to portraits and religious works attributed to him. He visited the court of regent Margaret of Austria in Mechelen in early 1521, and may have painted this portrait then. Unfortunately, it has been impossible to discover who commissioned it or why. It is nevertheless likely that it was painted between 1525 and 1530.” (Kok)

Gerard David’s Adoration of the Kings (Fig. 1) from about 1515 is an example of the romanticized imagery of Blacks that were depicted within artwork of this period.

Fig. 1 - Gerard David (Flemish, 14??-1523). Adoration of the Kings, about 1515. Oil on oak; 60 x 59.2 cm. London: The National Gallery, NG1079. Bequeathed by Mrs Joseph H. Green, 1880. Source: The National Gallery of Art, London

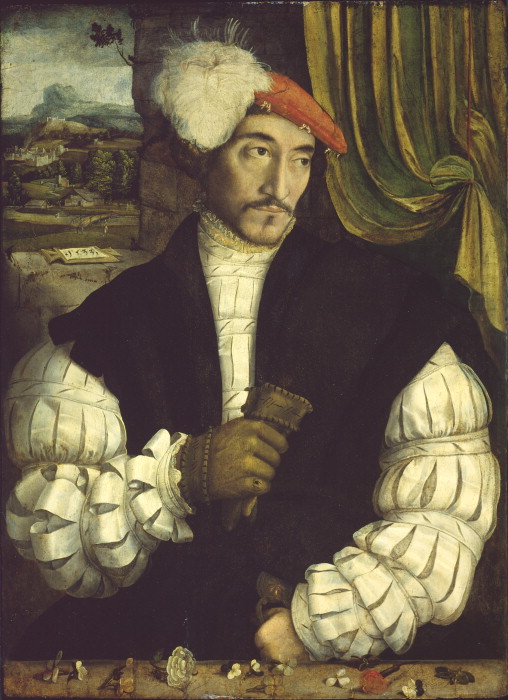

Jan Jans Mostaert (Dutch, c.1475-155/6). Portrait of an African Man, c.1525-c.1530. Oil on panel; 30.8 x 21.2 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2010. Purchased with the support of the Vereniging Rembrandt, with additional funding from the Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds, the Mondriaan Stichting, the VSBfonds, the BankGiro Lottery and the Rijksmuseum Fonds. Source: Rijkmuseum

About the Fashion

This artwork is a solo portrait of an unknown male, painted in the three-quarter pose that Mostaert was known for. The background is a solid blue-green color that compliments the deep red coloring of the sitter’s doublet. Garments of this type and color were a specialty of the Netherlands’ woven textile industry. The chemise under his doublet has embroidery details at the neckline similar to what we see in this close-up of Balthazar in David’s Adoration of the Kings (Fig. 2).

In Mostaert’s portrait, the African man’s doublet is double laced to his brown hose and the codpiece is revealed between the two leg panels. His black over-jacket is sleeveless with lacing details over the arm opening, resulting in open seaming with the red doublet exposed underneath. The lacing also acts as a closure at the neckline. The cording at the neckline has a hanging tassel detail. Mostaert has also included a baldrick and sword. The African man’s accessories are quite detailed. The bagged baldrick seems to be made of a textured fiber (perhaps leather velvet) with embellishment, in the form of embroidery or metallic filigree. We can discern a fleur de lys in the center with additional surrounding details. The hilt of the sword is similarly embellished with golden details. As we look to the extremities, his hands are gloved with a single tassel on the outer edge of the gauntlet. His head is adorned with a burnt orange colored bonnet with a seal in the center of the turned-up brim.

The museum offers an attribution for the seal, noting the “orange bonnet with a turned-up brim on which there is a gold or silver-gilt pilgrim’s badge of Our Lady of Halle, a town near Brussels that became a place of pilgrimage frequented by the Habsburg rulers of the Low Countries” (Kok).

A similar type of headdress is worn by Emperor Ferdinand I, son of Philip of Habsburg Austria in a c. 1520 portrait (Fig. 3).

Without a specific date, the relative fashionable-ness of the African man’s attire is up to speculation. The Rijksmuseum’s scientific examination of the wooden frame, provides a slightly wider window of possible dates: 1520 – 1535 (Kok). Menswear trends begin a dramatic shift in the early 16th century and if placed at the start of this window (1520) the African man’s attire is moderately out of date. Moving towards the end of the possible dates (1535), this apparel would certainly be on the less fashionable end of the apparel zeitgeist.

Comparisons to other portraits that span the relative range of what would have been fashionable during the periods in question are helpful. To start, Mostaert’s rendering of the textiles and double lacing style is quite similar to that of Portrait of the Young Man (1470) in figure 4. Similarly, the embroidered chemise and low-rounded, doublet of the Young Man with a Rosary (1500-1550) in figure 5 are nearly identical to the African man’s ensemble. In Breu’s, Portrait of a gentleman (1533), we see a clear example of the wide and voluminous styles of the mid-late 16th century (Fig. 6), leaving Mostaert’s painting as an homage to days past.

Another aspect we must consider is the element of race. According to the Rijksmuseum, “This is the earliest and only individual portrait of a Black African to have survived from the late middle ages and the Renaissance” (Kok). In Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (2012), Joaneath Spicer seeks to uncover the often hidden history of African descendants within Renaissance Europe, writing of the portrait:

“his embroidered pouch or purse stands out. Pouches are rarely featured so it may be a gift from a patron. It is decorated with fleurs de lys, the emblematic lily associated chiefly with the royal house of France but also with Margaret [Archduchess Margaret of Austria (1480-1530)] herself.” (87)

Notably, the paltrock is missing from the gentleman’s attire. The absence of this long over-gown, which would have concealed the hose, codpiece, and the bottom of the under chemise, potentially indicate the African man’s status within the court system’s stratification. Clothing was a commodity during this period, reflecting status and one’s proximity to wealth.

In A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Renaissance (2018), Elizabeth Currie touches on the international textile trade and its effect on fashion trends throughout Europe:

“Apparel was bequeathed, sold, stolen, and even hired. Any individual, moreover, could be involved at multiple points within this system, both selling and buying, being a recipient and in turn giving to others. Beneath this constant, restless passage of goods runs the solid fact of clothing’s value and potency the truth, in other words, of its fundamental importance to the world of the Renaissance.” (55)

Sitting for a portrait was an exclusive undertaking reserved for wealthy nobility or religious leaders. The sheer existence of this portrait of a Black man from this era displays his inclusion within the court hierarchy. Mostaert took care to create detailed, realistic facial features, portraying the gentleman in an honored position, rather than a servant’s role. Based on the contextual information, I would conclude that this apparel is slightly outdated when referencing to the 1525-1530 date range, however, the clothing items reflect higher quality garments and would be differentiated from the wardrobe of persons outside of the court life. Discovering this image and researching its details affirms our collective experience and representation in history as persons of the African diaspora.

Fig. 2 - Gerard David (Flemish, 14??-1523). Adoration of the Kings (detail), about 1515. Oil on oak; 60 x 59.2 cm. London: The National Gallery, NG1079. Bequeathed by Mrs Joseph H. Green, 1880. Source: The National Gallery of Art, London

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (Southern German). Emperor Ferdinand I (1503-1564), profile portrait, ca. 1520. Wood; 25.8 cm x 18.7 cm x 1.2 cm. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum, Picture Gallery, 6914. Coll. Kraushaar. Source: Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Gemäldegalerie

Fig. 4 - Biagio d'Antonio (Italian, Florentine, 14??–1516). Portrait of a Young Man, ca. 1470. Tempera on wood; 54.3 x 39.4 cm (21 3/8 x 15 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.100.68. The Friedsam Collection, Bequest of Michael Friedsam, 1931. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Adriaen Isenbrandt (Flemish, c.1490-1551). Young Man with a Rosary, 1500-1550. Oil on canvas, transferred to panel; 42.5 x 31.8 cm (16-3/4 x 12-1/2 in). Pasadena: Norton Simon Museum, F.1965.1.032.P. The Norton Simon Foundation. Source: Norton Simon Museum

Fig. 6 - Jörg Breu il Vecchio (German, 1475-1537). Portrait of a gentleman, 1533. Oil on board; 67.8 x 49.2 cm. Bergamo: University of Bergamo | ARTE | MODA ARCHIVE. Source: ARTE | MODA ARCHIVE

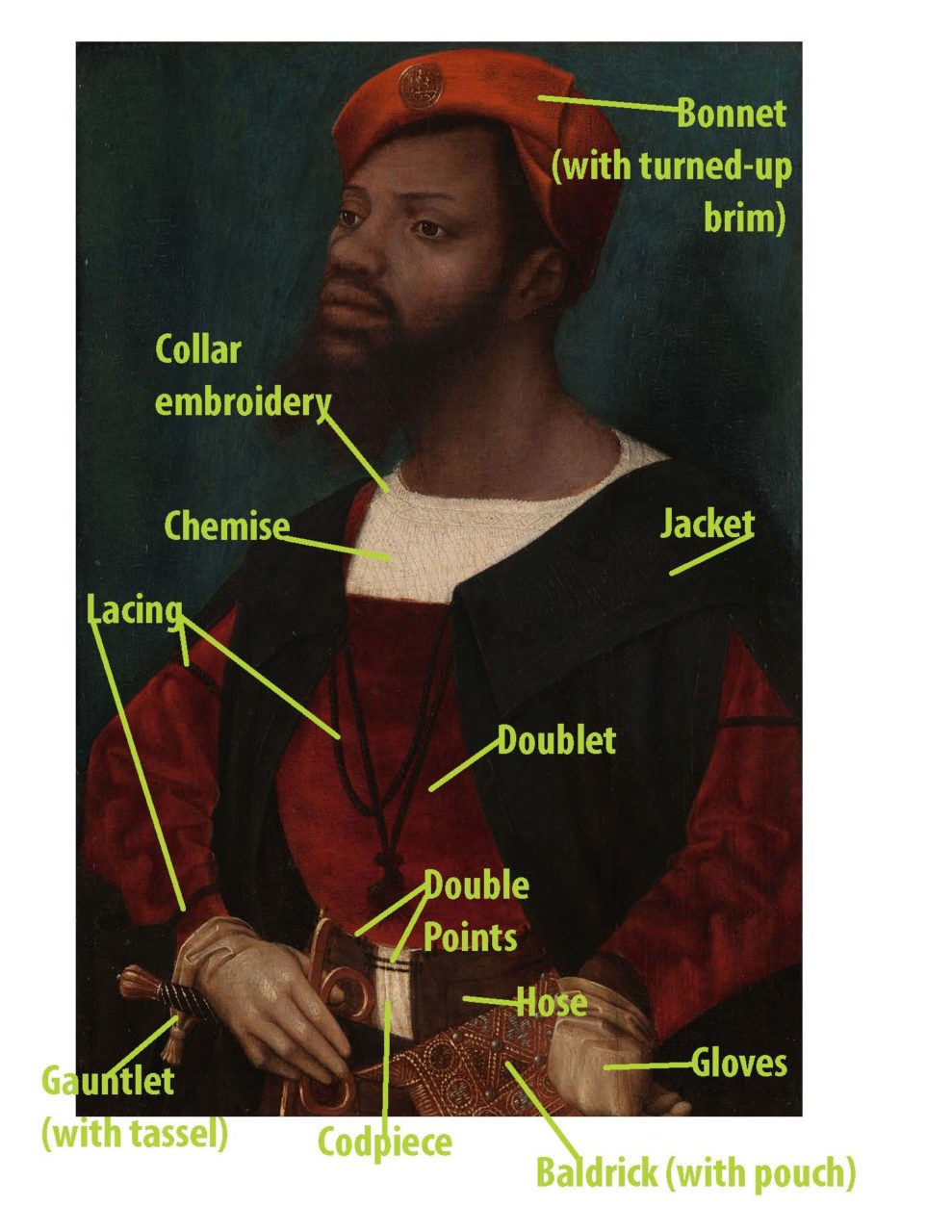

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Its Legacy

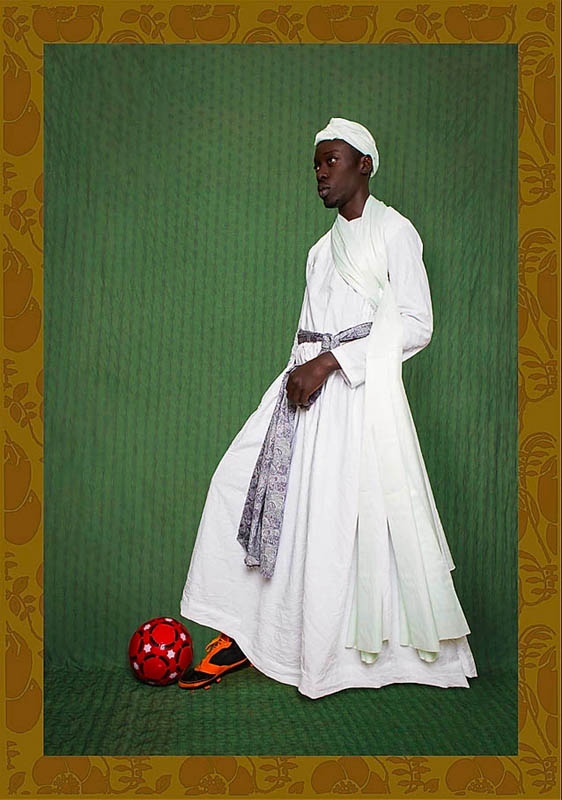

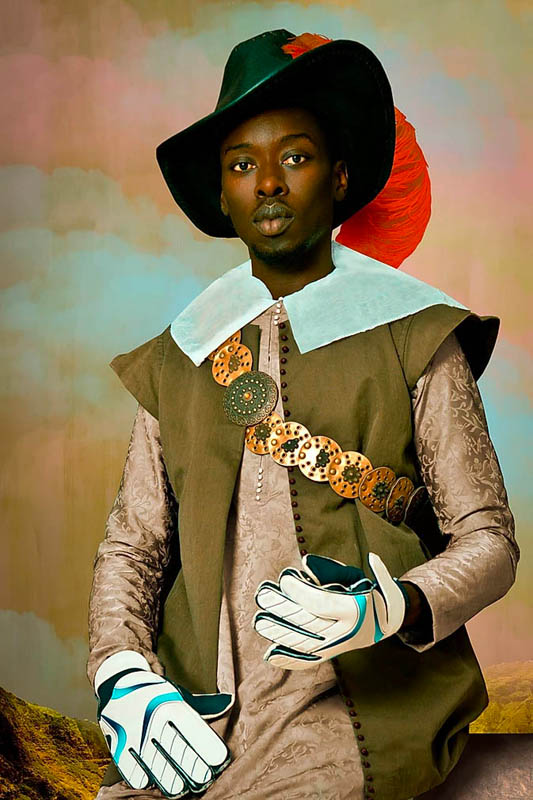

In his “Diaspora” series, Omar Victor Diop looks at Africans who from the 16th to 19th centuries played important roles beyond their home continent. Performing in costume, Diop embodies all of them in a sweeping history of portraiture – from Mughal miniatures to European court painters. One by one, he depicts Malik Amabar (1549-1626) (Fig. 7), an Ethiopian slave who became a minister and war chief in the village of Ahmednagar in India; Don Miguel de Castro (1643) (Fig. 8), Congo ambassador who visited Brazil and Europe; Juan de Pareja (1606-1670) (Fig. 9), the once enslaved assistant to painter Diego Velázquez and later free painter; Albert Badin (1747-1822), majordomo to the queen of Sweden Louise Ulrique of Russia; and Dom Nicolau (1830-1860), prince of Kongo and the first African leader to object to colonial rule in writing.

Fig. 7 - Omar Viktor Diop (Senegal, 1980-). Malick Ambar, 2015. Pigment inkjet print on harman by hahnemuhle paper; 60 x 40 cm. Diaspora Self-Portraits. Source: Omar Viktor Diop - Photographer

Fig. 8 - Omar Viktor Diop (Senegal, 1980-). Don Miguel De Castro, 2014. Pigment inkjet print on harman by hahnemuhle paper; 60 x 40 cm. Source: Omar Viktor Diop - Photographer

Fig. 9 - Omar Viktor Diop (Senegal, 1980-). Juan de Pareja, 2014. Pigment inkjet print on harman by hahnemuhle paper; 60 x 40 cm. Source: Omar Viktor Diop - Photographer

References

-

Currie, Elizabeth, and Bloomsbury Publishing. A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Renaissance. London [i pozostałe: Bloomsbury Academic an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1043046506.

- Kok, J.P. Filedt. ‘Jan Jansz Mostaert, Portrait of an African Man, c. 1525 – c. 1530’, in J.P. Filedt Kok (ed.), Early Netherlandish Paintings, online coll. cat. Amsterdam 2010: hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.431086 (accessed 2 February 2019).

-

“Project Diaspora.” Omar Viktor Diop Photographer Fine Art Fashion, n.d. https://www.omarviktor.com/project-diaspora.

-

Richardson, Catherine. Clothing Culture, 1350-1650, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/976442537.

-

Spicer, Joaneath Ann, Natalie Zemon Davis, and K. J. P Lowe. Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe: [Accompanies the Exhibition … Held at the Walters Art Museum from October 14, 2012, to January 21, 2013, and at the Princeton University Art Museum from February 16 to June 9, 2013]. Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/828784407.

- Velde, Carl Van de, and James Snyder. 2003 “Mostaert family.” Grove Art Online. 1 Feb. 2019. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000059880.