Soap Bubbles was the first of many paintings by Jean Siméon Chardin that depicted the life and curiosity of children. This painting combines his style of painting of everyday life with youth and innocence. In keeping with the subject, the clothing style is simple and unadorned basic everyday dress.

About the Artwork

J

ean Siméon Chardin was an 18th-century still life and genre painter from Paris, France. He favored realism and everyday subject matters for his genre painting style which was very contrasting to the Rococo movement at the time.

One can assume that his paintings of adolescent life were influenced by the birth of his daughter (Conisbee). Soap Bubbles was the first of many paintings by Chardin that depicted the life and curiosity of children. The sitter is the son of Jean-Jacques Le Noir, one of Chardin’s closest friends. The boy’s age is unknown, but one can see that he is in his adolescence. His nationality is French and he belongs to a family in the trade business located in Paris. The family owns many of Chardin’s work (Conisbee).

Chardin is best known for his genre paintings of everyday life. Soap Bubbles combines this style with youth and innocence. Some of Chardin’s related works are Girl with Shuttlecock and the House of Cards.

The reception is unknown, however several scholars believe some of his paintings carry a vanitas symbolism (Abrams 74-75) (Rosenberg 107-8). The portrait itself and many of Chardin’s works has a setting of innocents at play with no worries in world of turmoil, showing us that no matter your class status we all are important and that we are free and should be able to relax and enjoy life. The child’s costume and facial expression is a perfect reflection of this time, his attire is not impressive in the eyes of the haves, but his spirit is to be admired. His youth and casual feel also reminds the viewer of the pleasure of being young and having the mindset of a dreamer before we are cast into the real world of adulthood.

The subject of blowing bubbles was not a new one as you can see in the 1630 painting, Two Boys Blowing Bubbles, by Andriaen Hanneman (Fig. 1). The work shares the playfulness and curiosity portrayed in the painting amongst the boys, but differs in terms of class and wealth. If you look closely at figure 1, the garments are cleaner and possibly made of silk and linen compared to Chardin’s version. In the Chardin, the look also carries a commoner vibe, likely made of cheaper materials or it could be garments passed down from and older family member or friend, which could explain the possibly ripped arm socket.

Fig. 1 - Andriaen Hanneman (Dutch, 1603-1671). Two Boys Blowing Bubbles, 1630. Oil on canvas; 96.2 x 66 cm (37.88 × 26 in). West Palm Beach: Norton Museum of Art. Source: Wikimedia

Jean Siméon Chardin (French, 1699-1779). Soap Bubbles, 1733-34. Oil on canvas; 61 x 63.2 cm (24 x 24 7/8 in.). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.24. Wentworth Fund, 1949. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

T

hrough the first half of the 18th century children continued to dress as smaller versions of adults. The main boy in Soap Bubbles is wearing a torn brown jacket/waistcoat with narrow shoulders. The jacket is assumed to be flared and cropped at the knees. The sleeves are fitted with buttons and no cuff, which suggests this might be a waistcoat rather than a jacket. The sleeves are unbuttoned which gives a loose, carefree feel of the young.

Beneath this outer layer, he is wearing a plain shirt. The child is sporting curled side locks and a pulled-back Cadogan hairstyle, which was a trend for men and boys during this time period.

The materials in these garments are simple. Linen is most likely the materials used for the shirt and the jacket is possibly made of wool with linen or cotton twill. Silk twill was also used in coats/jackets but in this case most likely not because of the humble genre atmosphere.

As you can tell the painting only show the upper torso of the child, so one could think that the child is wearing what most children for in this time period, this would be the knee-length breeches. He may also be wearing a cravat but this could also be the collar of the undershirt. He is also most likely wearing basic shoes with some sort of buckle around the upper/mid-foot (Hill 428-32).

Rosenberg argues the boy next to him is wearing a tricorne hat/three-cornered hat, but I believe the hat in the painting is more like a playful version of a helmet (Rosenberg 107-8).

In figure 2, also by Chardin, we see similar plain clothing and Cadogan hairstyle. The difference is in the quality of the materials used in the garments and the cuff size. One child has no cuff (or wears a waistcoat) and the other is very extravagant in length, close to his elbows. The portrait has more of a regal and academic feel suggesting the young man’s importance in the future.

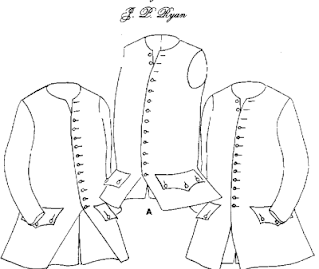

The 18th-century waistcoat pattern drawings in figure 3 and painting in figure 4, Young Boy with Dog by Bartholomew Dandrige, show a view of what the garment would look like if seen frontally, giving us a better understanding of the texture and folds. The surviving jacket in figure 5 also suggests what the garment would look like in real life, somewhat rugged and dirty.

Fig. 2 - Jean Siméon Chardin (French, 1699-1779). Young Man with a Violin (Portrait of Charles Theodose Godefroy), 1734-35. Oil on canvas; 74.5 x 67.5 cm. Paris: Musee du Louvre. Source: Wikiart

Fig. 3 - J.P. Ryan Patterns. 18th Century Waistcoat Pattern, 1750-1770. Source: Townsends

Fig. 4 - Bartholomew Dandridge (English, 1691-1755). Portrait of a Young Boy and His Dog, 1740s. Oil on canvas. Source: Wordpress

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown (English). Jacket, 1730–70. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.34.3. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1975. Source: The Met

The Sources

The costume in the main portrait was most likely made in France, because of all the tariffs and laws put in to place by the French government in order to promote and grow their local fashion textile industry. The garment was made by hand. The garment also looks like it could have been handed down from a family member or friend (Rosenberg 107-8).

The Ideal

In the portrait the boy is far from the ideal of polish and sophistication. You will notice in figure 1 there is a book placed in the corner indicating the children’s upbringing of wealth and sophistication. The boy is portrayed to be more of a commoner when compared to the other images. For example, the boy in figure 2 is given a clean and proper setting, positioning himself in an upright manner while learning music to pass his time as compared to blowing bubbles. When compared to figure 4, he seems less important. The children in figures 1, 2 and 4 seem to have a stature of wealth and future importance because of the fine materials such as silk in their garments and their more formal stances.

Its Legacy

Chardin’s Soap Bubbles was in the collection of early 20th-century French couturier Jacques Doucet until his 1912 sale, when it sold for Fr 300,500 (Met). It has inspired many artist to paint their own versions, one of the more well-known examples is by Édouard Manet. Manet and Chardin were both inspired by children for many of their paintings such as Manet’s Boy Blowing Bubbles (Fig. 6). The boy in the painting is thought to perhaps be Manet’s own son. In Shoe Shine with Chardin (Fig. 7), Robert Meling finds a whimsical way to show his love of Chardin’s work by having it in the background in his painting of boots.

Fig. 6 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). Boy Blowing Bubbles, 1867. Oil on canvas; 100.5 x 81.4 cm (39.6 x 32 in). Lisbon: Calouste Gublbenkian Museum. Source: Gulbenkian

Fig. 7 - Robert Meling (1954-). Shoe Shine with Chardin, 2011. Oil on canvas; (30 x 20 in). Source: Artmajeur

References:

- Abrams, Harry. Chardin: An Intimate Art. New York: Discoveries Inc, 2000. https://www.worldcat.org/title/chardin-an-intimate-art/oclc/915839512.

- AmericanRevolution.org. “French Fashion,” 2014-15. http://www.americanrevolution.org/clothing/frenchfashion.php.

- Brown, Susan, ed. Fashion: The Definitive History of History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. https://www.worldcat.org/title/fashion-the-definitive-history-of-costume-and-style/oclc/777654556.

- Conisbee, Phillip. “Chardin, Jean-Siméon.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed November 5, 2015. http://oxfordindex.oup.com/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T015989.

- Hill, Daniel Delis. History of World Costume and Fashion. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2011. https://www.worldcat.org/title/history-of-world-costume-and-fashion/oclc/731445106.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Soap Bubbles.” Accessed November 5, 2015. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435888.

- Rosenberg, Pierre and Renaud Temperini. Chardin. France: Prestel, 2000. https://www.worldcat.org/title/chardin/oclc/231844996.