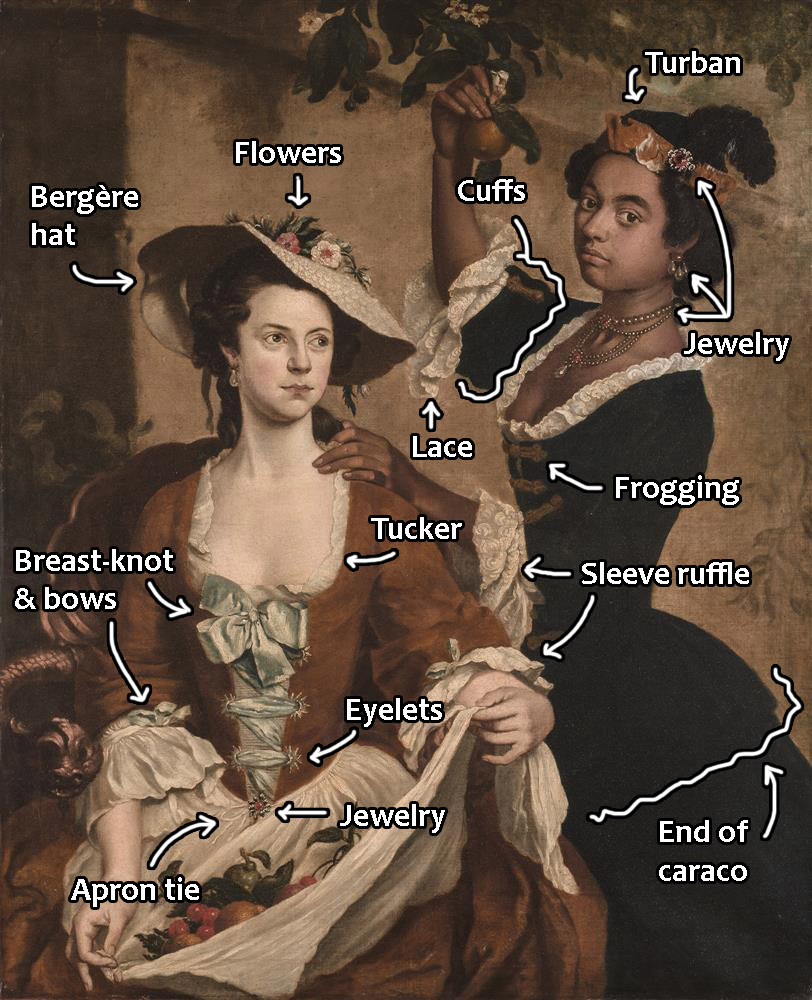

This painting of two 18th-century gentlewomen features fashionable trends in portraiture and clothing, including Orientalism, pastoralism, and masculine-inspired dress.

About the Portrait

This painting of two young women collecting fruit is attributed to English artist Stephen Slaughter (1697-1765). Slaughter studied under Godfrey Kneller from 1712 and worked abroad in Belgium, France, and Ireland over the next several decades (West). He returned to Britain for good in the late 1740s and was appointed Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, a position responsible for caring for and conserving the royal painting collection. In his biographical entry on Slaughter (2003), Shearer West notes:

“Slaughter’s figures tend to be stiffly posed, but he showed a facility for the depiction of costume… the ornate draperies of his sitters took precedence over any liveliness of gesture or expression.”

The 1745 portrait in figure 1 is a good example of this in his work; the silk gown is carefully rendered while the faces are rather flat.

While there is no date given by the museum, from an analysis of the fashion (next section) we can tell that it probably dates to c. 1750 – that is, from between 1745-1755. Slaughter was most prolific in the 1740s.

This painting is currently titled Young Woman with Servant, but this seems to be a relatively new name with an updated description to support the renaming. The painting is referenced in books and online by two other names: between 1986 and at least 2003 it is cited as Two Women Gathering Fruit and before 2019 as Portrait of Two Society Women (Tortora 240, Lowery 224).

The Wadsworth Atheneum’s “Curatorial Narrative” claims that the Black woman is a servant:

“Despite an apparent affection between these young women, the seated figure is clearly of privileged social status while her standing companion is a servant. A number of English portraits from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries depict female subjects, particularly children, in the company of a favorite non-European servant. The setting in an enclosed garden, often with ‘antique’ props such as the grotto chair, and the gesture of offering fruit are common to this category of pictures. The plumed head band worn by the servant girl is a romanticized suggestion of ethnicity which differentiates race.”

This seems to be a narrow reading of the painting. We assert instead that this depicts a Black sitter treated as equal to a white sitter in an 18th-century continental European context. A similar piece dating to the 1760s of gentlewoman Dido Belle and Lady Elizabeth Murray (Fig. 2) is also lauded as such, but this painting may actually be more representative of an equal or near-equal relationship. While Dido’s painting feeds into old tropes of servant-and-master portraiture that the Wadsworth describes (Fig. 3), this painting avoids almost all of them. And uniquely, the Black sitter in this image is looking at the viewer while the white sitter is looking over at her rather than also confronting the viewer (Fig. 4). The agency and perspective in this painting seems to be the possessions of the Black sitter. Both women are holding fruit, rather than having one gift it to the other as a sign of bounty and subservience (Waterfield 144).

It is also the Black woman here who is depicted holding an orange and its blossom directly, rather than the white one (Fig. 3). In Masterpieces of American Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1986), Margaretta Salinger describes the symbolism:

“The decorative orange tree… is characteristically in fruit and flower at the same time. Customarily a symbolic allusion to purity, marriage, and fertility, the tree is also evidence of the wealth and luxury that its cultivation required. In the late seventeenth century, following the fashion set by Louis XIV when he built the giant orangery at Versailles, a demand for this delicate bloom was created among European society.” (14)

She also is the one with more lavish lace and jewelry – usually a symbol of greater standing – and the only indication of exoticism is her small matching turban. Everything else she wears is just as fashionable as what her companion wears, if not more. This is rare; Black women and servants usually are dressed more simply in comparison, or dressed entirely in fantastical clothing that resembles Ottoman Turkish or Asian styles (Waterfield 144) (Fig. 4).

While the Wadsworth has chosen to confine this painting to the genre of master-and-servant portraiture, we venture to say that it is a more unique and respectful depiction of a Black sitter than the famous double portrait in figure 2 and gives life to research proving that slavery and servitude were by far not the only lot of people with darker skin tones in the 18th century (Bindman 12). Other respectful depictions of Black people around this time in Europe existed in life sketches (Fig. 5) and genre paintings (Fig. 6).

While we do not know the names of either woman in this painting, they join ranks with such distinguished people as Ignatius Sancho (Fig. 7) and the Chevalier Saint-George, who were formally painted as respected Black individuals in this century.

Fig. 1 - Stephen Slaughter (British, 1697-1765). Lady and Child, 1745. Oil on canvas; 130 x 104 cm. Dublin: National Gallery of Ireland, NGI.797. Bequeathed, Sir Hugh Lane, 1918. Source: NGI

Fig. 2 - David Martin (Scottish, 1737-97). Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay and Lady Elizabeth Murray, ca. 1768. Oil on canvas. Scotland: Scone Palace. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Follower of Hyacinthe de Rigaud (French). Elisabeth l'Hermite d'Hieville (Madame la Marechal de Montesquiou), ca. 1700. Oil on canvas; 160 x 120 cm. Lot 229, 03 December 2016. Source: Auction FR

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Distinguished lady with maid and valet, 19thc copy after 1744 original. Gouache on paper; 16.5 x 20 cm. Stockholm: Hallwyl Museum, XXXII: Cc03.. Source: LSH

Fig. 5 - Antoine Watteau (French, 1684-1721). Huit études de têtes (Les Charmes de la Vie), 1715-16. Red chalk, black stone and white chalk, heightened with brown pastel and wash; 26.7 x 39.7 cm. Paris: Le Louvre, INV 33383. Purchase, 1858. Source: Louvre

Fig. 6 - Jean-Baptiste Pater (French, 1695-1736). Le Dénicheur de moineaux (The Sparrow Catcher), First half of 18th century. Oil on canvas; 59.5 x 73 cm. Paris: Musée Cognacq-Jay, J 91. Source: Paris Musées

Fig. 7 - Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788). Ignatius Sancho, 1768. Oil on canvas; 73.7 x 62.2 cm. Ottowa: National Gallery of Canada, 58. Purchased 1907. Source: NGC

Stephen Slaughter (British, 1697–1765). Two Women Gathering Fruit, ca. 1750. Oil on canvas; 122.6 x 99.7 cm (48 1/4 x 39 1/4 in). Hartford, CN: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 1987.1. The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund. Source: Wadsworth Atheneum

About the Fashion

In the Survey of Historic Costume (2003), Phyllis Tortora and Keith Eubank describe women’s clothing in the second quarter of the eighteenth century:

“Two new styles replaced the loose sacque. The robe à la Française had a full, pleated cut at the back and a fitted front. The robe à l’Anglaise had a close fit in the front and at the back. Generally gowns had open bodices and skirts, which allowed the display of decorative stays and petticoats… Some garments consisted of skirts and tops.” (239-240)

Two of these styles are visible on our sitters – the robe à l’anglaise and an ensemble consisting of a petticoat and bodice. Skirts during this time were called petticoats or simply ‘coats’ (Cunnington 91). The overall silhouette is visible on the standing women in figure 8. In Costume in Pictures (1964), Phyllis Cunnington discusses what was worn underneath the petticoats in order to achieve the bell shape:

“The hang of the skirt depended on the underwear… The hoop or hoop-petticoat from 1710 to 1780, and for Court wear until 1820, was variously distended with cane, wire or whalebone. The shape also varied. The bell hoop, worn throughout the hoop-period, was dome-shaped, the fan hoop, 1740s and 1750s, was pyramidal; the oblong hoop, very wide from side to side, was fashionable from the 1740s to 1760s.” (93)

From the flared shape of the black skirt we can tell that the women’s silhouettes match the rounded bell shape in figure 8. Both women are also wearing loose linen shifts and boned stays for cleanliness and support (Fig. 9). The large sleeves of the shifts are gathered to a band near the forearm and then a gathered cuff is attached to the other side of the band.

Their hairstyles are quite fashionable; the majority of women during this time wore their hair simply (Fig. 8) or covered by caps (Lowery 223). These ladies have pinned their hair up in the back and styled curls at the side fronts like the blonde woman in figure 10.

Interestingly, these women also share jewelry styles: the dark pink gemstones with silver settings that the Black sitter wears is echoed by a piece of jewelry on the band of the white sitter’s apron. This is a unique touch and must have meant something personal. Are they sisters? Something more?

Black Sitter

The woman on the right is wearing a fashionable but informal gown consisting of a jacket (caraco) and matching petticoat (Sholtz 47). Its decorative gold frogging at the front and heavy-looking cuffs are modeled on military uniforms; this style of trimming is sometimes called Brandenbourg (Fig. 11) (Cumming 87). In the 1780s, the fashion was given the name redingote (French, from the English ‘riding coat’). Men’s clothing was not acceptable for women to wear, but aspects like jackets and military lace (braid) were commonly used for riding habits (Fig. 12) and often made their way into daywear like the gown in figure 13, which is similar in cut to the Black sitter’s (Blanco F. 236).

The sitter’s bodice fastens at the center front, as with most articles of dress during this time; a tiny slice of her shift is visible towards the top where the bodice gapes a bit. Women’s bodices normally closed with straight pins, but it may be the case that the frogs (gold fasteners) on her bodice acted as the method of closure here – as the buttons do in figure 13 – in a touch of masculine style (Blanco F. 236).

The sitter’s ensemble is probably silk, given the luxury of the rest of her ensemble, but might be fine wool. An extant example of a silk caraco and petticoat can be seen in figure 14. Black gowns were not common at this time, as the goal was usually to use the most expensive and decorated bright fabric to demonstrate one’s wealth (Steele n.p.) and the Rococo period was particularly fond of pastel colors. This varied by country: In England black was often connected with advanced age, poverty, or a state of mourning, while in some areas of Italy it was required of all noblewomen by law (Steele, Sharp 24). Maybe she is in mourning or has links to Venice; perhaps she simply liked its stark simplicity.

The sitter has a ‘suit of lace’ (matching edging) on her sleeves and tucker (Fig. 15) (Blanco F. 141). Her lace is delicate and would have been extremely expensive; the other woman has a simple ‘suit of linen’ in comparison. She is wearing an elaborate set of jewelry with pearls and gemstones set in silver. Springer’s Illustrated Guide to Jewelry Appraising: Antique, Period, and Modern (2012), describes this style of earring, popular throughout the eighteenth century:

“Society was not disappointed in a special design called girandolé. This was a pendant earring with three small precious stones or pearls suspended from a main disk, crescent, ribbon swirl, or horizontal bar. The girandolé design was immediately embraced by the fashion-conscious women of the period.” (61)

The rose-colored surmount (center piece) is echoed by the two gems in her two-tier necklace and the one on her small turban. They may be precious or made of paste (Fig. 17) (Cumming 150). While pearls were often painted on Black sitters in order to emphasize their dark skin tones, that does not seem to be the goal here, as her skin tone is neither especially dark nor pearls her only jewelry (Childs 140). This may simply be her best or favorite set of accessories that she was proud to wear for this sitting.

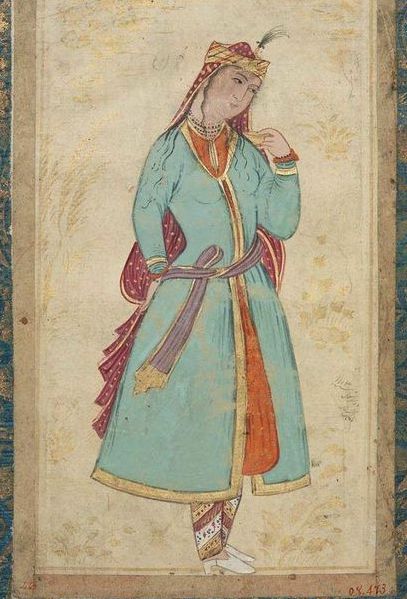

The last aspect of her dress to discuss is her turban, which smacks of exoticism; as mentioned above, Black sitters were often painted wearing non-Western clothing so that they would stand out (Waterfield 140). However, the rest of her clothing is European daywear, which is unusual for that trope. See figures 3 and 4; the Black sitters have full outfits in Indian and Turkish style. It seems instead that her turban is meant to be fashionable in the same way that the white sitter’s hat is – simply as a stylish element, and not necessarily a garment that forces a connection to her skin color. This is fairly unique in Black portraiture of this time, but possible because fashionable turbans and other ‘Oriental’ accessories were sometimes worn by white women in this way over otherwise Western clothing (Fig. 17). While the style was called turquerie, few aspects of the headwear were ever recognizably Turkish (Fig. 18). Our sitter’s turban instead resembles a style worn several decades earlier in Iran (Fig. 19).

Her dress and hair are fashionable and her jewelry and lace are formal and expensive; she appears to be a high-ranking woman with taste and the means to dabble in trends.

Fig. 8 - Stephen Slaughter (British, 1697–1765). Detail of The Betts Family, ca. 1746. Oil on canvas; 73.7 × 61.6 cm. London: Tate, N01982. Bequeathed by Mrs A. Sealy 1905. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (American). Stays, 1740-60. Linen, leather, whalebone; cf 38.1 cm (15 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.3330a–d. Source: MMA

Fig. 10 - Allan Ramsay (Scottish, 1713-1784). Portrait of a Lady, formerly called Flora Macdonald, 1752. Oil on canvas; 74.9 x 62.2 cm. Edinburgh: National Galleries Scotland, NG 1884. Bequest of Mrs Morag Macdonald 1937. Source: NGS

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (British). Sir Charles Firebrace (1680–1727), ca. 1720. Oil on canvas; 121 x 96.5 cm. Sudbury: National Trust, Melford Hall, 926885. purchased from Sir Richard Hyde Parker and Lord and Lady Camoys, 2002. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 12 - Thomas Hudson (British, 1701-1779). Portrait of a Young Woman of the Fortesque Family of Devo, ca. 1745. Oil on canvas; 127 x 101.6 cm. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B2001.2.246. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 13 - Jonathan Richardson the elder (attr.) (British, 1667–1745). Portrait of a Lady, ca. 1730. Oil on canvas; 127 x 99.1 cm. Forres: National Trust for Scotland, Brodie Castle, 73.108. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (Norwegian). Ensemble, 1730-60. Silk. Oslo: Kunstindustrimuseet, OK-08212. Gift, 1909. Source: Digitaltmuseum

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (English or European). Sleeve ruffle, 1760-85. Cotton with linen needlework. VA: Colonial Williamsburg, 1985-128,1. Museum purchase. Source: CW

Fig. 16 - Designer unknown (Russian). Girandole earrings, ca. 1760. Amethyst, diamond, silver, gold; 5.4 cm long. Geneva: Christie's, Lot 269, Sale 1350, 15 November 2007. Source: Christie's

Fig. 17 - Adriaen Hanneman (Dutch, 1604-71). Mary, Princess of Orange (1631-1660), 1655?. Oil on canvas; 120 x 98 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 405877. Source: RCT

Fig. 18 - Jean-Étienne Liotard (Swiss, 1702-1789). Dame et sa servante au bain, ca. 1738-1742. Pastel on parchment; 71 x 53 cm. Geneva: Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1936-0017. Source: MAH

Fig. 19 - Mu'in Musavvir (attr.) (Persian, 1617–1701). Young Woman with a Cup, 1702/3. Ink, gold and watercolor on paper; 24 × 15.8 cm. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 08.473. Source: MFA

White Sitter

The woman on the left is dressed more simply but still somewhat trendily. From her accessories and gesture it appears that she may be engaging in one of the other fashionable trends of this time: pastoralism (Koda 26). Country life was heavily romanticized by the aristocracy (Fig. 20), who often commissioned portraits of themselves in ‘peasant’ costumes (Fig. 21). In Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715-1789 (1985), Aileen Ribeiro describes that “rural costumes” became popular in the middle of the century:

“a rather stylized simplicity… straw hats and flowers could make passable costumes for shepherdesses. Playing at rural simplicity was an eighteenth-century pastime; fashionable ladies queued up to be painted as milkmaids, dairymaids, hay-makers and shepherdesses.” (181)

Key signifiers of this kind of look are flowered straw hats, front-laced bodices (imitating the look of stays worn without clothing on top), baskets of fruit or flowers, shepherd’s crooks, and flowing linens like shifts and aprons (Ribeiro 33). This woman’s bodice also has rather unique large embroidered eyelets, giving it a ‘costumey’ feel amongst a lineup of 1750s dress, and her gown is much simpler than what a woman would normally request to be painted in.

While the women in the ‘conversation piece’ in figure 8 are wearing fitted-back gowns, in formal portraits women often wore robes à la française with billowing back pleats (also called a ‘sack’ or ‘saque’ gown) (Fig. 22). Formal dress also included sleeve ruffles (engageantes, Fig. 15), and often a cap and fichu (neckcloth). The woman in figure 22 has been painted outside and thus is wearing a hat, but unlike our sitter, she wears a cap properly underneath it. Earrings and necklaces were also often worn in portraiture, and if a woman donned an apron for a portrait it is usually a very sheer and decorative piece, not one of plain linen (Fig. 23). Women like the two in this portrait did not need aprons to protect their gowns, only to accent them, so transparency and fineness were valued (Baumgarten 47). The sitter’s lack of cap, necklace, and lace, along with her plain apron, stand out and contribute to the pastoral look.

Her gown also seems quite plain despite the elaborate ribbon running down the front. As far as we can tell from the front, it is a simple closed anglaise (meaning that it has a fitted back and a drop-front petticoat) of brown silk taffeta; hardly a statement of luxury. Compare her dress to the one in figure 24, which is similar in cut: they both feature an open front with stomacher, spiral-laced closure, a central bow, and sleeve ruffles that are attached to the shift. Yet the white gown has additional pearls, bows, an open front for a blue petticoat to show through, and much finer sheer ruffles. Its fabric also has a luxurious sheen, but this may be the result of a different painting style. Additionally, despite a similar method of closure, the eyelets for the lacing are not visible. Perhaps the large eyelets on the brown gown were meant to exaggerate a home-sewn, amateur look?

An extant open-style anglaise can be seen in figure 25 along with its matching petticoat. Clothing depicted in paintings is rarely identical to what the sitter actually wore, and in some cases was entirely invented by the artist (Fortune 30). This example, dated 1745-50, gives a better idea of what a high-status informal day gown looks like for this era, replete with rich fabric and complex trim. The broad ‘winged’ cuffs are common in this era, and many gowns also featured robings, or pleated strips, down the front edges (visible in figures 8, 22, and 23) (Edwards 52, 53).

Her center-front bow, or ‘breast-knot,’ is probably fake and was pinned on once the bodice was laced together, as were the small matching bows on her shift cuffs; shifts rarely had drawstrings in this era (Cunnington 29, Burnston). The little jewel on her apron-band is somewhat of a mystery; it may have been sentimental, or it may be a trend during this time that is as of yet unresearched. A similar piece of small metal decoration is visible on the apron in figure 23 when zoomed in. A small bow is visible underneath both hers and our sitter’s; their apron ties have been drawn around back to the front and tied at center, as seen on the cook in figure 26.

Lastly, she wears a flat tilted hat, a key aspect of the ‘shepherdess’ and ‘country girl’ characters. While the flowers and rumpled look are in keeping with the pastoralist theme (Fig. 21), similar hats were fashionable for ordinary dress. Straw bergères like the one seen in figure 22 were popular from 1730 until the end of the century and had a flexible brim and low crown (Cumming 20). Tellingly, they were called ‘shepherdesses’ and ‘milkmaid hats’ because they were popularized by this very trend (Cumming 20).

Fig. 20 - John Faber the Younger (after Philippe Mercier) (British, c. 1684-1756). Rural Life: The Dairymaid's Occupation, ca. 1710-1756. Mezzotint. London: British Library, 2010,7081.2281. Source: BL

Fig. 21 - François Hubert Drouais (French, 1727–1775). The Prince (1736–1818), and Princess (1737–1760), Condé, Dressed as Gardeners, 1757. Oil on canvas; 142 x 95 cm. Aylesbury: Waddesdon Manor, 131.1996. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 22 - Henry Pickering (attr.) (British, c.1720–1770/1771). Miss Dixie, ca. 1750-55. Oil on canvas; 121.9 x 99.1 cm. Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery, NCM 1894-112. Gift from Mr J. Henry Jacoby, 1894. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 23 - William Verelst (attr.) (British, 1704–1752). Portrait of Elizabeth Beckford, ca. 1743-45. Oil on canvas; 242.9 x 166.2 cm (95 5/8 x 65 1/2 in). New York: Sotheby's, Lot 105, 4 June 2015. Source: Sotheby's

Fig. 24 - Thomas Hudson (British, 1701–1779). Portrait of a Lady, 1750. Oil on canvas; 127.3 x 102 cm. Dulwich Picture Gallery, DPG578. Gift from Charles Fairfax Murray, 1911. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 25 - Designer unknown (British). Robe à l'anglaise, 1745-50. Blue silk damask. Moscow: Shoe Icons Museum, 2549. Source: Shoe Icons

Fig. 26 - Artist unknown (British). Elizabeth Hickman (d.1784), Cook to the Corporation, mid-18th C. Oil on canvas; 124 x 100 cm. Stratford-upon-Avon Town Hall, TH06. Source: ArtUK

While it may appear that the Black woman in this portrait is of a higher status due to the amount of jewelry and fine lace that she is wearing, it is more likely that both are of similar status or at least were close enough to be painted this way. Their outfits are equally trendy, if not quite in the usual fashion: one has chosen to engage in pastoralism, romanticizing the life of the working class, while the other engages in Orientalism and is playing with masculine military style and foreign cultures. Both are problematic in their own way and rely on aristocratic English privilege; Elizabeth the cook in figure 26 would probably have not thought much of such trends.

At the end of the day, these women were able to take off their country hats and Turkish turbans and not suffer through the hard chores and Orientalist racism which would come from being an actual country girl or Turkish person in England. Given this fact, it is interesting that the Black woman has chosen to interact with the trend; she may have understood ‘Turkish dress’ and racism towards foreigners in a very different light to the racism that she herself must have experienced as a Black woman living in eighteenth-century England.

Its Legacy

This painting appears within another painting, done nearly two hundred years later in Thoresby, the home where it descended (Fig. 27). It went to auction in 1986 and was bought by the Wadsworth Atheneum, where it has been since.

There has been some recent debate as to the status of the sitters. Sarah Murden of the “All Things Georgian” blog has researched the painting closely, raising questions about the supposed servitude, unearthing the Thoresby portrait and many other fascinating finds that align with our conclusions here. Recently Murden was sent another version of the portrait (Fig. 28) that has erased the Black sitter. We consider this portrait to be a later copy, likely from the 19th century based on the painting style.

Because Black people were so often depicted as servants in historical Western painting, some might assume her to be a servant too (Wadsworth). But as discussed above, the painting subverts too many common elements of that historical trope to be an example of it. (If Dido Belle’s double portrait can be lauded as a rare example of near-equal status, than this should certainly be accorded that same honor.) On the other hand, the white sitter is not dressed nearly as luxuriously, so others have subversively wondered if she is the Black sitter’s servant instead (Boyd). However, discussion has so far not yet taken the pastoralist theme into account concerning the white woman’s clothing, which is why we have put forth the possibility that they are of equal status or near to it.

We look forward to finding future art inspired by this lovely painting.

Fig. 27 - Marie-Louise Roosevelt Pierrepont (British, 1889–1984). The Artist's Daughter with Her Dog at Thoresby Hall (Lady Rozelle Raynes), Mid-20th century. Oil on canvas; 76 x 63.5 cm. Newark, UK: Thoresby Courtyard, MLP2008-294. Gift from Lady Rozelle Raynes, 2008. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 28 - Artist unknown. Copy of Two Women Gathering Fruit, 19th century. Oil on canvas. Source: All Things Georgian

References:

- Baumgarten, Linda, John Watson, and Florine Carr. Costume Close-Up Clothing Construction and Pattern, 1750-1790. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/984073157

- Bindman, David. “The Black Figure in the European Imaginary.” in Childs, Adrienne L., Susan H. Libby, and David Bindman. The Black Figure in the European Imaginary. London: D Giles Limited, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1049992472

- Blanco F., José, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Boyd, Ebonique. “Young Woman And Servant, A Discussion On Race And Historical Perceptions.” Budget Collector, 19 June 2020. Accessed 20 June 2020. https://www.budgetcollector.org/young-woman-and-servant-stephen-slaughter/

- Burnston, Sharon. “Cut and Construction.” The Cognitive Shift, 2018. Accessed 19 July 2020. http://www.sharonburnston.com/shifts/shifts_construction.html

- Childs, Adrienne L. and Susan Libby. Blacks and Blackness in European Art of the Long Nineteenth Century. London: Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1023250029

- Cumming,Valerie, Phillis Cunnington, and C. Willett Cunnington. The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/751449764

- Cunnington, Phillis. Costume in Pictures. London: Studio Vista Ltd, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1172347923

- Edwards, Lydia. How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1126368318

- Fortune, Brandon Brame. “Studious Men are Always Painted in Gowns”: Charles Willson Peale’s Benjamin Rush and the Question of Banyans in Eighteenth-Century Anglo- American Portraiture.” Dress, 29:1 (2002), 27-40. Taylor & Francis Online

- Illustrated Guide to Jewelry Appraising Antique, Period, and Modern. Miller, Anna M., ed. Springer Verlag, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/861214430

- Koda, Harold, Andrew Bolton, and Mimi Hellman. Dangerous Liaisons: Fashion and Furniture in the Eighteenth Century. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1014407748

- Lowery, Allison. Historical Wig Styling: Ancient Egypt to the 1830s. New York: Routledge, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1106138975

- Murden, Sarah. “Art Detectives: Young Woman with Servant.” All Things Georgian (blog), November 15, 2018. https://georgianera.wordpress.com/2018/11/15/art-detectives-young-woman-with-servant/.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe, 1715-1789. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1985. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/647582299

- Salinger, Margaretta M. and John K. Howat. Masterpieces of American Painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Random House, 1986. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/819761321

- Sharp, Samuel. Letters from Italy: Describing the Customs and Manners of That Country… Dublin: Henry & Cave, 1767. Google Books

- Sholtz, Mackenzie Anderson. “Caraco Jacket, 1715-1785.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Steele, Valerie. The Black Dress. New York: Collins Design, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/757101055 | Google Books

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. New York : Fairchild Publications, 2000. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/39154857

- Waterfield, Giles. “Black Servants.” In Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits. London: National Portrait Gallery Publ, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/834455426

- West, Shearer. “Slaughter, Stephen.” Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 17 Jul. 2020. OAO (subscription required)

- “Young Woman with Servant.” Wadsworth Atheneum, 2019. Accessed 15 July 2020. Argus