Beetle-wing embroidery: a colonialist fantasia and exotic fad in nineteenth-century England and America.

Fig. 1 - Collector unknown (British). Beetles, before 1951. Gloucestershire: Snowshill Manor and Garden, NT 1336177. Source: UKNT

Beetle-wing (or elytra) embroidery rose to fame in eighteenth-century India and was appropriated by English visitors for use during the period in which the East India Company (1757-1858) and then the British military (1858-1947) occupied the country. Victorian gentlewomen in England, America, and Australia attended balls with thousands of elytra glittering like emeralds on their light cotton dresses, making statements about their wealth, power, and worldliness.

This form of embroidered decoration is inextricably linked to colonialism and it has been an item of fantasy and exoticism for more than two hundred years. But how could high-society women bear to wear…bugs?

Origins in India

Elytra are the hard casings made of chitin that shield insects’ fragile wings (singular ‘elytron’). The jewel beetle (Fig. 1), family Buprestidae, has particularly beautiful elytra that come in a range of colors (Angus). Those used for embroidery like this are generally green with a blue-purple shimmer. Jewel beetles live across the globe and their elytra have been used for decoration and jewelry by a variety of cultures, including the Jivaro people in Peru and Ecuador and the Naga in India and Myanmar (NHM). They are harvested ethically and are available for purchase today as a byproduct of the food industry (Homfray).

Victorian elytra embroidery has its roots in Mughal India (1526-1857). While there was a tradition of using elytra in Rajputani painting by at least the 17th century, the craft more likely stems from the use of elytra in houshold and personal adornment (Fig. 2), which may be much older.

Beetle-wing embroidery was made all over India during the Mughal era, but the court in Jaipur took the art to new levels in the eighteenth and nineteenth century (Fig. 3), which is likely where the English fell in love with it. It was done on garments for all genders and ages, and the elytra are almost always cut up into sequins and used as small parts of overall designs rather than as primary materials (Fig. 4). It is common to see them in sequined borders, in buteh (often called ‘paisley’) motifs (Figs. 4-5), and tiny but present in allover patterns with multicolored foil.

The elytra were generally paired with zardozi (gold embroidery) and the embroidery was often done on brightly colored cottons or fine silks (Leslie 85). Extant men’s jamas, turbans, and shoes; women’s cholis and sarees (Fig. 5), children’s belts, and even hand fans in museums all sport elytra.

The earliest elytra-embroidered garments for Western export are done with Indian embroidery styles on Western clothing, like the late 18th-century pumps in figure 6. Only later did a distinct embroidery style for export develop.

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (Indian (Uttar Pradesh)). Huqqa mat, 1800-1850. Cotton, velvet, metal strips, sequins, floss silk, embroidery, couching; 53.4cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, IS.1:1-1999. Source: VAM

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (Indian (Rajasthani)). Jama, before 1855. Red cotton, silver-gilt gota (tinsel), beetle elytra. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 05563(IS). Source: VAM

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (Indian (Rajasthani)). Detail of Jama, before 1855. Red cotton, silver-gilt gota (tinsel), beetle elytra. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 05563(IS). Source: VAM

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (Indian (Gujarati)). Sari, before 1855. Silk, gold-wrapped thread, beetle elytra; 267 x 110cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 0638(IS). Source: VAM

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Indian for British export). Shoes, Last quarter of the 18th century. Elytra, linen, metal thread. Toronto: Bata Shoe Museum, P94.0014. Source: BSM

The Nineteenth Century

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (Scottish). Mary Jane MacDougall's presentation gown, 1822. Cotton, silk, beetle elytra. Oban: MacDougal of Dunollie Preservation Trust, #OBNMD:2010.34. Source: Twitter

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (Indian for British use). Beetle-wing dress, 1827-31. Cotton, elytra, metal thread. Cheltenham: The Wilson, NT1943.74. Source: Twitter

India was considered a colony of the British Empire from 1757 until 1947, first under the control of the East India Company and then the British Crown. Her peoples, commodities, and products were oppressed, plundered, and appropriated, and the craft of beetle-wing embroidery is part of that legacy.

Elytra dresses experienced their first burst of popularity in England by the 1820s, though Englishwomen in India had likely been donning it since at least the 1780s (Libes 5). Several extant gowns in Scotland, including the one in figure 7, are decorated with pieces of elytra along the edges of the dress. By the 1830s, large, ornate designs were common and the buteh motif had taken hold (Fig. 8). This would be the predominant pattern from the 1830s until the 1880s.

Most Victorian elytra dresses use each elytron in its original state, so that it is clearly a wing-casing, or broken up into large chunks (Fig. 9). They also cover enormous swaths of the dress, making it impossible not to notice the shimmering green. The Indian style of embroidery, on the other hand, tended to use tiny pieces, and they can be difficult to spot (Figs. 3-5). Often, a dress’ claim to fame was the sheer amount of elytra used. “There are 5000 beetle wings in this dress!” one 1898 article crowed (SFE). Elytra are relatively tough, but they do break, as can be seen in figure 9. Using the full wing-casing – which is sharp and not at all flat – as decoration made a dress less versatile than if they were cut into smaller, smoother sequins, but it did attract more attention.

A particularly unique aspect of the Western dresses is their biomimicry: Elytra were sewn onto gowns in imitation of live beetles (Fig. 10). This practice may reflect the quintessentially Victorian interest in naturalism – ordering and categorizing the natural world – and it is not seen in existing Mughal embroidery.

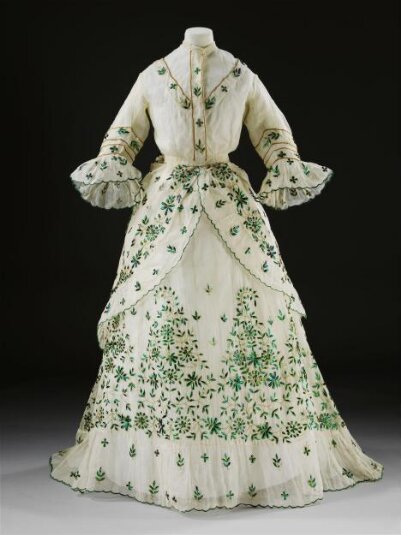

Elytra embroidery was used predominantly on white cotton dresses (Fig. 11) (Angus). Fine muslin was a symbol of India, just as zardozi and elytra were, so it may come as no surprise that many of the women who wore these dresses were those who had visited India themselves, often as the wives of soldiers in the East India Company or the British army (Libes 10).

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (Scottish). Detail of beetle wing dress, ca. 1868. Cotton, metal-wrapped thread, elytra. Fort William: West Highland Museum, 1993.022. Source: Highland Threads

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown. Detail of Stole, Mid-19th century. Cotton, elytra, metallic thread. London: The John Bright Collection. Source: JBC

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (Probably British, but Indian-made). Two beetle-wing dresses, ca. 1850. White cotton, gold thread, beetle elytra. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, #AC10375 2000-40-2AB. Plate 29 in Fukai Akiko, Luxury in Fashion Reconsidered (Kyoto: The Kyoto Costume Institute, 2009). Source: La Gatta Ciara

While butehs remained relatively popular, the embroidery designs did change with the fashions – sometimes out of necessity. These dresses generally followed the lines of fashionable styles even if the materials were unusual, so when skirts started to be broken up by ruffles and tiers in the mid-1850s, the larger designs changed to suit (Fig. 12). The intricate, multi-layered bustle gowns of the 1870s and 1880s (Fig. 13) and complicated styles of the 1890s gained increasingly delicate embroidery as well. The export market may also have pivoted to embroidering the elytra onto cotton bobbinet (Fig. 14) during the 1880s and 1890s, likely in order to increase the range of uses at its destination. Embroidered muslin lent itself well to dresses; embroidered net could be applied to nearly anything.

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown. Dress, ca. 1860. Cotton organdy, elytra, metallic thread; (b 36, w 28 in). Visaginas: Alexandre Vassiliev Foundation, 2019.2.3.14ae.CW.DR.C1860.US. Source: Augusta Auctions

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (British). Dress, 1868-69. Cotton, gilded metal thread, & elytra. London: Victoria & Albert museum, T.1698:1 to 5-2017. Given by Kathy Brown. Source: VAM

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (Indian (Tamil) for export). Detail of a textile fragment, Mid-19th century. Beetle elytra, metal-wrapped thread, bobbinet; 41 x 51 cm. Terrassa: Centre de Documentació i Museu Tèxtil, 9102. Tórtola Valencia, Carmen. Source: IMATEX

Most beetle-wing dresses from this era are white, but there is evidence that darker dresses existed, mostly from textile fragments and embroidery done on black bobbinet (Fig. 15). Most of the work was likely done in India and exported as a flat textile to be made into a dress once it arrived at its destination. Some embroidery was done in particular shapes to suit the final dress – the piece in figure 15 was designed to be applied to the full length of a princess-line dress’ front panel. Elytra were also embroidered onto accessories like purses (Fig. 16), shawls, and hats.

British demand transformed beetle-wing embroidery. No longer was it made in unique one-off pieces for the Mughal elite; by the mid-nineteenth century there was a booming export business in Chennai on India’s southeastern coast (then referred to as Madras). The embroidery and work produced for the Western market was not only less fine than work done on extant garments made for Indian use, but the designs also became standardized. Identical floral and buteh patterns can be seen across a variety of textile fragments in museums today. Another standard of mid-century dresses included thick green scalloping embroidery around the hems of dresses (Leslie 85). Note the gown in figure 17 (WHM); the edge of the fabric beyond the embroidery was not cut to shape, indicating a fast and somewhat careless pace of production. This is reflected across several similar dresses (Libes 10).

In the 1880s, women began to turn to silk satin for their gowns rather than cotton, perhaps desiring something a little more impressive in an era of industrialiation (Fig. 18). Color also began to seep into designs, first in a soft ivory or candlelight shade (Fig. 19) and then in variations of green, black, and gold – attractive when paired with the elytra (Leslie 85).

While extremely privileged women had worn beetle-wing gowns to court in the 1830s, by the 1890s it seemed to be primarily the domain of the eccentric (if it ever was anything more than that in the first place). Oscar Wilde’s wife Constance Lloyd was written up in the papers for wearing a beetle-wing dress in 1886 (Libes 13). Tourists could pick up pieces of elytra embroidery in bazaars across India; Bostonian Everett Wendell bought several dresses at a market in the early 1880s, some of which may be decorating his mother’s dress in figure 19 (Libes 9). Museums often fielded donations of beetle-wing textile pieces from such travelers who had likely picked them up as souvenirs (Libes 12). Even more than a century after its introduction into Western fashion, elytra embroidery was still seen as exotic and may have only been worn for special and fanciful occasions.

Fig. 15 - Students of the Hobart School (Indian (Tamil) for export). Textile, ca. 1880. Gold thread, elytra, & black muslin net; 117 x 48cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, IS.1917 to E-1883. Source: VAM

Fig. 16 - Designer unknown (Indian for export). Unfinished bag, Mid-19th century. Silk plain-weave couched with gold metallic flat strips, appliquéd beetle wings and sequins; 21 x 36.5 cm (8 1/4 x 14 3/8 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 52.1339. Gift of Miss Anna P. Revere. Source: MFA

Fig. 17 - Designer unknown (Scottish). Barbara Morrison's beetle wing dress, ca. 1868. Cotton, metal-wrapped thread, elytra. Fort William: West Highland Museum, 1993.022. Source: Highland Threads

Fig. 18 - Louise Winter (British). Detail of silk evening dress, 1892-4. Silk, metal thread, elytra; 86cm bust, 60cm waist. Museum of London, 60.22/2. Source: MOL

Fig. 19 - John Singer Sargent (British (active America), 1856-1925). Mrs. Jacob Wendell (Mary Barrett, 1832–1912), 1888. Oil on canvas; 153 × 91.4 cm (60 1/4 × 36 in). New York: New-York Historical Society, 2012.21. Gift of the Roger and Susan Hertog Charitable Fund and Jan and Warren Adelson. Source: N-YHS

The Twentieth Century

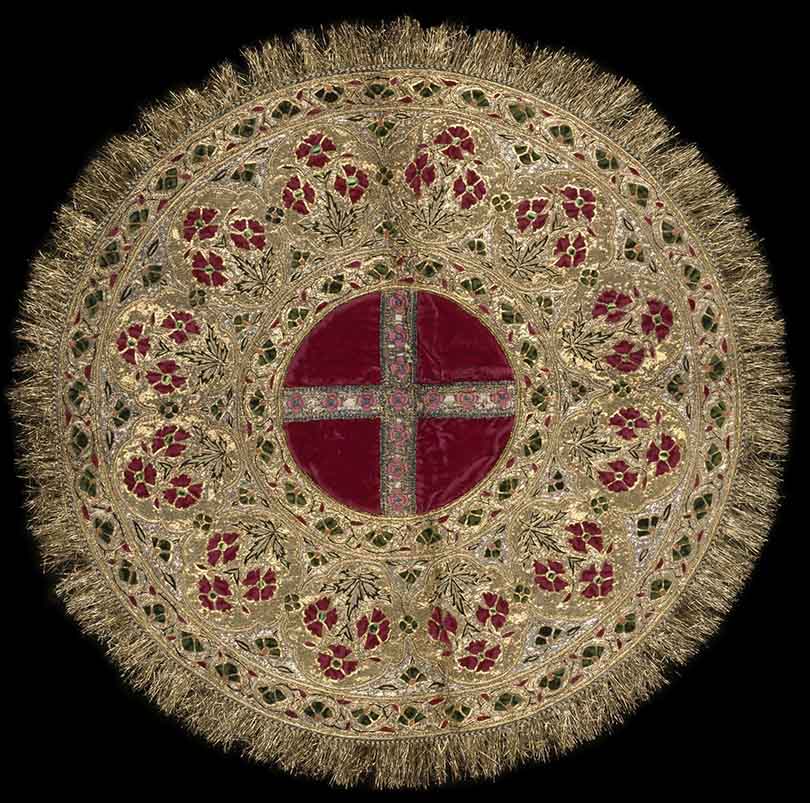

Fig. 20 - Jean-Philippe Worth (French, 1856–1926). The Peacock dress, ca. 1900 - 1902. Gold & silver thread, elytra, silk taffeta. Derbyshire: Kedleston Hall, NT 107881. Source: Antique Trader

Fig. 21 - Designer unknown (Italian for English use). Evening dress, ca. 1907. Silk, satin, lace, metal, elytra. Shropshire: Attingham Park, NT 609790. Source: UKNT

While the heyday of beetle-wing dresses in the Anglosphere was restricted to the nineteenth century, women continued to wear elytra into the 1920s.

The most famous of all the so-called ‘beetle wing gowns’ is probably Lady Curzon’s, which was made for the 1903 Delhi Durbar and is colloquially known as the ‘Peacock Dress.’ Seen from behind in figure 20, it is covered in zardozi done in the shape of peacock feathers (a symbol of India and her bounty), and in the center of each feather’s ‘eye’ is an elytron (Leslie 86).

It was designed in 1903 by Jean-Philippe Worth of the House of Worth and was meant to be a respectful gesture to the craftsmanship of Indian artisans. Curzon and her husband were the viceregal couple, however – extensions of British power in India – so their very presence at the Durbar remains a symbol of subjugation. Her dress went over well with the British reporters, but it’s likely that the gesture fell somewhat flat for the Indians in attendance.

Curzon’s gown is immense, and an outlier in the pool of existing beetle-dresses. Its goal was to represent multiple facets of Indian artistry, and indeed – you probably can’t see the individual elytra when you look at the dress! That aspect alone represents a return to Mughal embroidery style, even if the sheer excess is still quite British in its opulence. The point of this dress, unlike all of the others (Fig. 21), is not the elytra, which are simply a small part of a larger design.

Beetle-wing embroidery in the usual Western style continued to be used on evening dresses in the teens and twenties, and colors like black, green, gold, and even pink were used in addition to the typical white (Fig. 22). Purses and accessories continued to be manufactured, providing a place for the heavy and ornate embroidery that the style had developed into (Fig. 23). The evening dresses of the 1920s, after all, were hardly the kind that could bear heavy metal embellishments (Fig. 24). But the ’20s were its last hurrah (until the present day) and the style appears to have faded out of the public consciousness soon after.

Fig. 22 - Designer unknown. Green & gold beaded dress, ca. 1921. Silk chiffon, beads, elytra; (length 49 in). New York: Augusta Auctions, Lot 360, November 2, 2011. Source: Augusta Auctions

Fig. 23 - Designer unknown. Opera Coat, ca. 1925. Elytra. Fairbanks: Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum. Source: FAAM

Fig. 24 - Designer unknown (Probably British). Beetle-wing dress, ca. 1926. Ivory tulle, gold embroidery, & beetle wings; bust 81cm (32 in). London: Kerry Taylor Auctions, Lot 130 (General Fashion & Textiles, Tue, 14th May 2013). Source: KTA

Stage & Theatrical Costumes

Costume designers have taken advantage of the fantastical look of beetle elytra for more than a century. Designer Alice Comyns-Carr’s crocheted and bewinged Lady Macbeth costume for Dame Ellen Terry caught the attention of Oscar Wilde in 1888 (Berman 147). While it is better known by the larger-than-life painting done by John Singer Sargent in 1889 (Fig. 25), the dress still exists today, conserved at her home (Fig. 26).

Costume balls in the late nineteenth century often saw guests dressing up in beetle wings, in the colors of one, and even as a beetle. One newspaper article even reports a drag queen (then called a ‘female impersonator’) donning them for her act in 1881 (Libes 14). The dress in figure 27 was likely used for some kind of costume event, as it was purchased at a department store and the elytra embellishments are roughly appliquéd on a non-matching fabric.

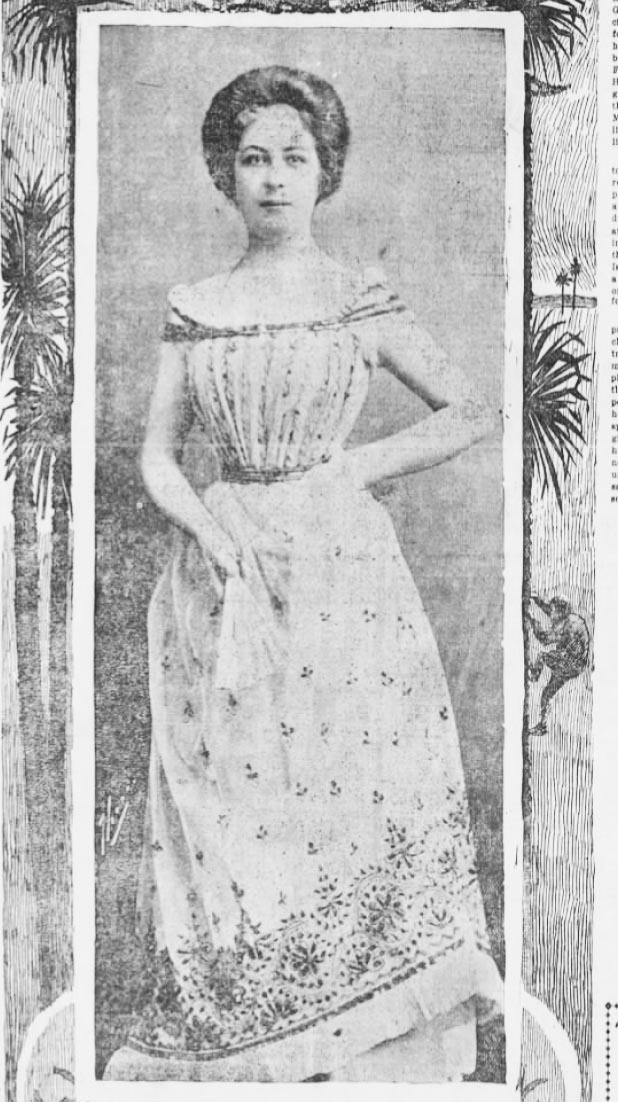

American actress Adora Andrews (1872 – 1956) wore a gown for stage events in the late 1890s that was reported to have five thousand elytra sewn to it (Fig. 28). A sensationalist article titled “Here’s the Girl in the Wonderful Beetle-Wing Dress” in the July 17th, 1898 issue of the San Francisco Examiner claims:

“At that rate if very many gowns were made of the material beetles would soon become extinct in India… The material for this gown was given to [her] by an Indian prince… On his return to India he had the material manufactured and sent it as a gift to [her]. The gown was fashioned in New York and bade fair at first to be of more use as a curiosity than as wearing apparel.”

Newspapers had a field day with the story, which ran repeatedly all over the US and Canada until at least 1923 (GIH). But 5,000 elytra (already a number likely to have been exaggerated) wasn’t enough; papers changed it to 15,000 in short order and then attributed the gift to a raja. Andrews’ gown was a curiosity, reported as “Queer Fancies in Dress,” and the publicity tells us that elytra-embroidered garments were by this point costume rather than clothing.

Far more recently, several beetle-wing-adorned dresses have appeared in movies. Designer Colleen Atwood likely took influence from Comyns-Carr when designing for Snow White and the Huntsman (2012) (Fig. 29) and they made a more subtle appearance on a historically-inspired green damask gown (Fig. 30) in 2007’s Elizabeth: The Golden Age, designed by Alexandra Byrne. Beetle elytra have a mysterious, fantastical quality that makes them useful in costumes like these, continuing to draw attention even after centuries.

Fig. 25 - John Singer Sargent (and Alice Comyns Carr) (British, 1856-1925). Ellen Terry as Lady Macbeth, 1889. Oil on canvas; 221 × 114.3 cm. London: Tate, N02053. Presented by Sir Joseph Duveen, 1906. Source: Tate

Fig. 26 - Alice Comyns-Carr (designer) & Adaline Nettleship (maker) (British, 1850– 1927 & 1856–1932). Macbeth dress, 1888. Cotton, silk, lace, elytra, glass, metal. Kent: Smallhythe Place, NT 1118839.1. Source: UKNT

Fig. 27 - C & H Dickins & Jones (British department store). Court gown, 1890s. Silk satin, metal thread, elytra appliqués. Crewkerne: Lawrence's Auctioneers, Lot 1551, 20 May 2016. Source: Saleroom

Fig. 28 - Louis Thors (photographer) (Dutch (active America), 1840-1910). Adora Andrews, "Here's the Girl in the Wonderful Beetle-Wing dress", 1898. The San Francisco Chronicle. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 29 - Colleen Atwood (American, 1948-present). Beetle-wing dress for Charlize Theron's Queen Ravenna, 2012. Silk taffeta, silk chiffon, beetle wings. Source: Women's Wear Daily

Elytra have also been co-opted for haute couture in recent years. Design team On Aura Tout Vu sent elytra-studded garments down the runway looking more theatrical than ever in 2013 (Fig. 31). Belgian designer Dries van Noten took his interest in beetle-wing fashion a step further and created faux elytra (also a Victorian tradition, as it turns out) for his Fall/Winter 2015-16 collection (Fig. 32). Are we soon to see a resurgence in this age-old fad? Only time will tell.

Fig. 30 - Alexandra Byrne (British, 1962-present). Cate Blanchett as Queen Elizabeth, 2007. Damask, satin, lace, metallic thread, elytra. Source: Costumer's Guide

Fig. 31 - On Aura Tout Vu (French, active 1998-present). S/S Couture Paris, S/S 2013. Elytra. Source: Now Fashion

Fig. 32 - Dries van Noten (Belgian, 1958-present). 3D paillettes at Paris Fashion Week, F/W 2015-16. Source: Vogue

References:

- Angus, Jennifer. “Nature’s Sequins.” Cooper Hewitt | Smithsonian Design Museum, September 14th, 2018. Accessed June 6th, 2021. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2018/09/14/natures-sequins/

- Berman, Jessica Schiff. A Companion to Virginia Woolf. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1226379909

- GIH, “Queer Fancies in Dress.” The Grand Island Herald (Grand Island, Nebraska), 30 Aug 1923, 7.

- Homfray, Sarah. “Beetle Wings for Embroidery.” 2021. https://www.sarahhomfray.com/myshop/prod_1899068-Beetle-wings-for-embroidery-greenblue.html

- Leslie, Catherine Amoroso. Needlework Through History: An Encyclopedia. London: Greenwood Press, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/494467219

- “Glory in a Host of Entomological Spoils: Beetle-Wing Embroidery and the Exhibition of India in Anglo-American Dress, 1780–1903.” Dress 47:1 (2021), 79-94, DOI: 10.1080/03612112.2020.1833537

- NHM, “Unexpected Animal Parts.” Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Accessed June 5th, 2021. https://nhm.org/unexpected-animal-parts

- SFE. “Here’s the Girl with the Wonderful Beetle-Wing Dress.” The San Francisco Examiner (17 Jul 1898).