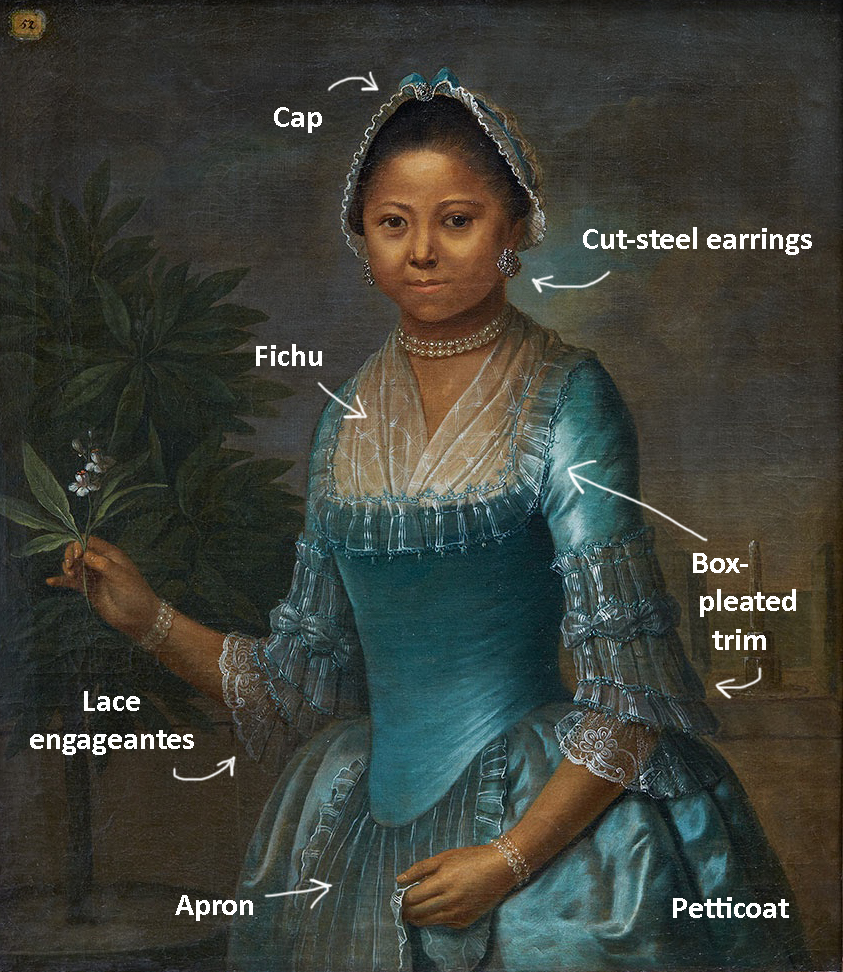

This young woman dressed in blue silk edged with lace demonstrates fashionable simplicity for the 1770s and may have lived in the bustling port city of Amsterdam.

About the Portrait

The Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom, acquired by the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2020, is important for its compelling portrayal of a young woman of color in the 18th century. The artist who painted it has been identified as Jeremias Schultz (1722/3-1800), a Berlin-born painter who worked primarily in the bustling port city of Amsterdam (AGO).

The painting is currently dated to the mid-18th century, but a careful examination of the clothing reveals that it was probably painted around 1775. The Dutch ‘golden age’ of painting occurred in the previous century, but skilled artists like Cornelius Troost continued to produce detailed portraits of Holland’s inhabitants (Fig. 1). While the treatment of the fabric in the AGO’s portrait is not entirely typical of mainstream European schools of painting, similar styles can be found by other artists who chose to work outside of that norm (Fig. 2).

The sitter is this painting is anonymous. She is a young woman, probably between 12-14 years of age, with medium-dark skin, dark brown eyes, and dark hair puffed in a fashionable style and kept under a transparent cap. Because her clothing is fine and her family wealthy enough to commission a high-quality portrait, she is clearly a free woman of color. It is not likely that she or her family were once enslaved, unless her situation was similar to that of her contemporary Dido Belle, who had an elite white father (Fig. 3) (Braimah). Her show of wealth here makes it more likely that she and her family were never enslaved, and lived as free, wealthy members of society wherever this was painted. Free Africans had settled in England since the Renaissance and married into white English families, but it was far more difficult to avoid enslavement in other countries (Kaufmann 113, 124).

She is holding an orange blossom delicately in her right hand. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has this to say of orange blossoms as symbols in paintings:

“The white orange blossom symbolizes both marriage and purity, while the fruit [is] a sign of fertility…Orange trees, although fashionable in Europe, were expensive rarities in the colonies. The presence of one here reinforces the sitter’s wealth.” (MMA, “1729”)

There is a tree – possibly a frangipani (plumeria) – behind her at left, and an obelisk or possibly a fountain at right. Obelisks, fountains, and other Neoclassical structures were popular background features for paintings in the mid-eighteenth century, in the tradition of Joshua Reynolds and Johann Zoffany; the painting in figure 4 has a Greek pediment peeking over the trees for a similar effect.

That the sitter is Netherlandish would explain her relatively modest hairstyle during the time in which Queen Marie Antoinette was becoming famous for foot-tall hair. Such wild fashions were primarily the domain of extremely wealthy Frenchwomen, though they were worn in other countries. It is also possible that her family is relatively newly arrived from a country or area of the Netherlands less in tune with the most changeable of French fashion – or also that she disliked such hairstyles and preferred a more modest look.

No matter her location or history, the young lady in the portrait is possessed of wealth, bearing, and no small amount of style.

Fig. 1 - Cornelis Troost (Dutch, 1696-1750). Portrait of a Lady in a Painted Oval, 1725. Oil on canvas; 49.5 x 40 cm (19.5 x 15.7 in). Private Collection. Source: White Rose Fine Art

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (Slovakian). Portrait of girl in blue in front of harpsichord, 1776-1779. Oil. Source: History of Fashion

Fig. 3 - David Martin (Scottish, 1737-97). Portrait of Dido Elizabeth Belle Lindsay and Lady Elizabeth Murray, ca. 1778. Oil. Scone Palace. Source: English Heritage

Fig. 4 - Anton Raphael Mengs (German (active Spain), 1728-1779). Portrait of Isabel Parreño y Arce, Marquesa de Llano, 1771-72. Oil on canvas; 135 × 98.5 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-3277. Source: Rijksmuseum

Jeremias Schultz (1722/3-1800). Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom, mid-18th century. Oil on canvas; 80 × 56.2 cm (31.5 x 22 in). Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 2019/2437. Purchase, 2020. Source: Art Gallery of Ontario

About the Fashion

The sitter’s ensemble has touches that show it is meant for daywear, like her cap and apron. Her dress is what modern historians call a ’round gown,’ which does not have a separate matching petticoat. She has accessorized with transparent silk: an apron, a fichu (handkerchief), and a cap; she also wears large cut-steel earrings and a set of double-stranded pearl jewelry.

If it opens in the front, her dress would simply have been called a ‘nightgown’ in the 1770s (Lewandowski 98). The petticoat and bodice are sewn together at sides and back, the front of the petticoat ties around the waist with a drawstring, and the bodice pins shut (Fig. 5). It is a fairly informal mode of dress, and was more common for a child than an adult for a formal portrait. It is also possible that, unlike most 18th-century dresses, hers fastens in the back with laces. All children wore dresses before the age of seven, and girls continued to wear back-lacing dresses until puberty (Fig. 6) (Callahan 55). This young woman may be just around that age, or this may have been painted by an artist who did not think the front closure was important enough to paint in.

The trimming on her gown is what places the style of the gown firmly in the 1770s. Notice the box-pleated sections of striped silk organza that decorate her neckline and her arms, as well as the puffed lines of trim around the center of each arm. This manner of trimming became popular in the late 1760s and continued to be used into the 1780s. The painting of Princess Sophie Friederike, ca. 1774, in figure 7 is an excellent example of this fashion. Patterned, transparent trims were all the rage in the 1770s, and it is possible that the orange-blossom girl is wearing an older gown that has been re-trimmed to be up-to-date with French styles (Chrisman-Campbell 17).

In her 2002 book What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America, Linda Baumgarten describes the fashion of the 1770s:

“[W]omen’s fashions of the 1770s and 1780s were neither sober nor practical. In addition to trimmings and flounces, gown skirts were sometimes drawn up in puffs with drawstrings or tapes…Tall hairstyles trimmed with pearls, ribbons, and padding emphasized the frivolous appearance of fashionable clothing.” (219)

The princess in figure 7 is a good example of the fashions in Europe at the time, complete with tall, buckled (curled), powdered hairstyle and small, almost useless cap (Tortora & Eubank 241). The sitter with the orange blossom, however, doesn’t have the same hairstyle. This may be explained two ways: first, that she is very young. Children often sported toned-down versions of what their parents were wearing, and in the 1770s especially rarely put their hair up so high. Second, it may be that she lives outside of Amsterdam – perhaps in the smaller city of Deventer (AGO). While some ladies did take part in French hair fashions, many did not, especially those in smaller locales. Her hair is styled with a small amount of height at front, suitable for a conservative 1770s look that cannot be confused with earlier decades. Her cap is the same: fashionable enough, yet not as extravagant as it could be (Fig. 8). Depending on her hair texture, it is possible that she may have been able to achieve the puffed look without relying on pomade and hair pieces (known as “rats”) as most white European women did, which explains the lack of powder.

Janea Whitacre describes eighteenth-century caps in her entry “Head Wear, Men’s and Women’s, 1715-1785″ for the encyclopedia Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe (2015):

“The cap was part of fashionable indoor wear. Often it was made of the same materials as the neck handkerchief, elbow ruffles, and tucker. These pieces made up a ‘suit of linen’ or ‘suit of lace,’ which identified the materials they were made of… Sometimes fashion commanded that the apron match as well, but it was still sold separately.” (141)

The sitter’s ‘suit of lace’ does not fully match, though we cannot see her cap well enough to know whether it is coordinated to another part. Her fichu has a windowpane pattern and her trims are striped. Her forearms, on the other hand, are partially covered by fine Chantilly lace engageantes (sleeve ruffles). The most fashionable of women would have had enormous ones, sometimes in several tiers (Fig. 9), which tells the viewer that this sitter is less ostentatious (Doering 12). Her apron and fichu, however, are so fine as to be completely transparent. Aprons like this were decorative only, and showed the viewer that the sitter was wealthy enough to purchase such transparent, fine silk or cotton, and that she did not have to do any manual labor, which would have required a sturdier apron (Doering 7).

Under her dress, she must be wearing a chemise, a pair of stays, and, judging by the sideways-width of her skirt, probably a pair of pocket hoops (Fig. 10) or small panniers. This silhouette, with width pushed sideways rather than all around or to the back, places her after the 1750s and before the late 1770s in terms of fashion (Tortora & Eubank 240). The German National Museum has this to say of pocket hoops:

“As an alternative to [panniers, pocket hoops] could be strapped on, giving the dress on top of it a similar silhouette. They were comfortable to wear, and the pockets that were sewn into them could be used by the wearer to carry all sorts of accessories.”

She is surely also wearing heeled shoes, stockings, at least one petticoat, and a pair of pockets underneath her gown (Doering 11-14).

Her earrings appear to be cut-steel (Fig. 11), a less expensive material popularized in the mid-18th century that in effect could rival diamonds (Armstrong 182, Ward 295). In her book The Jeweler’s Eye (1986), Laura L. Vookles describes the construction process:

“Cut steel, a jewelry material mentioned as early as the Elizabethan era, was produced in quantity by the middle of the eighteenth century. A steel jewel consisted of a shaped back plate which was pierced with as many holes as the design required, and into each of faceted mild steel stud was riveted. Such studs could be worked and polished easily, and mini 18th century examples have as many as 15 facets.” (22)

While it may initially have simply been a cheaper substitute for diamonds and marcasite, cut-steel jewelry became popular in its own right. Isabel Parreño y Arce, Marquesa de Llano in figure 12 wears large girandole earrings and a triple-tiered necklace, all of cut steel, to accessorize her already rich and glittering attire. This sitter’s multiple strands of pearls were often the necklace of choice for the most fashionable of European women (Figs. 4,7) even Marie-Antoinette made the switch to pearls in the 1780s. Even women in the colonized portions of the Caribbean enjoyed multi-strand pearl jewelry (Fig. 13).

The orange-blossom girl is not wearing an extremely fashionable gown for the mid-1770s – a gown with a stomacher would have been more formal, and a polonaise, levité, or jacket-and-petticoat combination might have been more current choices, as fashion plates tend to show (Fig. 14). While round gowns, or “nightgowns,” were becoming more popular at this time, few women chose to be painted in them due to their simplicity and informality.

This portrait of an unknown young woman is an example of restrained luxury. Whether such restraint is due to her position or personal taste, she remains fashionable without indulging in excesses.

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (American). Round gown, ca. 1780. Textile: blue plain weave worsted wool; off-white plain weave linen lining; linen thread; overall: 124.46 cm (49 in). Historic Deerfield, HD 2003.27.1. Source: Aylwen Gardiner-Garden

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (British (dress), Chinese (textile)). Girl's dress, ca. 1760. Silk, hand embroidered in silk thread. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.183-1965. Source: VAM

Fig. 7 - Georg David Matthieu (German, 1737-78). Prinzessin Sophie Friederike, ca. 1774. Oil on canvas; 85 x 75 cm (33.4 x 29.5 in). Schwerin: Ludwigslust Palace, G 177. Source: Kultur Stiftung der Länder

Fig. 8 - John Singleton Copley (American, 1738-1815). Detail of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Izard (Alice Delancey), 1775. Oil on canvas; 174.6 x 223.5 cm (68 3/4 x 88 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 03.1033. Edward Ingersoll Brown Fund. Source: MFA

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown (Russian). Portrait of an Unknown Woman, 1770s. Oil; 91 x 72 cm. St. Petersburg: The Hermitage, ЭРЖ-1993. Source: SHM

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (German). Pocket hoops, ca. 1770. Linen, undyed, plain weave; stiffening: fish bone sticks; l. 36 cm. Nuremberg: German National Museum, T2479. Source: GNM

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (English). Georgian Cut Steel Drop Earrings, ca. 1800. Iron and cut steel; 5 x 1.8 cm (2 x ¾ in). London: Antique Jewelry Company, 934C. Source: AJC

Fig. 12 - Anton Raphaël Mengs (German (active Spain), 1728-1779). Portrait de Isabel Parreño Arce, Ruiz de Alcaron y Valdes, marquise de Llano (1751-1823), ca. 1765. Oil on canvas; 72 x 61 cm (28.35 x 24.02 in). Paris: Artcurial, Lot 143, Old Masters, March 23, 2017. Source: Auction FR

Fig. 13 - Agostino Brunias (Italian (active Caribbean), 1728–1796). Free West Indian Dominicans, ca. 1770. Oil on canvas; 31.8 x 24.8 cm (12.5 x 9.75 in). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. Source: MMA

Fig. 14 - Claude Louis Desrais (French, 1746-1816). Young lady on her morning walk, in a Polonaise trimmed in pipes, two watches at her sides, coiffed in a new, elegant pouf, 1778. Fashion plate. Galerie des Modes, 9e Cahier, 6e Figure. Source: Mimic of Modes

References:

- “1729 | Mrs. Francis Brinley and Her Son Francis.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/12602

- AGO, “Portrait of a Lady Holding an Orange Blossom,” Art Gallery of Ontario. https://ago.ca/collection/portrait-of-a-lady-holding-an-orange-blossom

- Armstrong, Nancy. Jewellery: An Historical Survey of British Styles and Jewels. Guildford: Lutterworth Press, 1973. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/3207512

- Baumgarten, Linda. What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/612301448

- Braimah, Ayodale. “Dido Elizabeth Belle (1761-1804).” BlackPast, 3 June 2014. www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/belle-dido-elizabeth-1761-1804/

- Callahan, Colleen. “Children’s Dress and Fashion, 1715-1785.” in Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- “Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America.” Colonial Latin American Review 12:1 (2003) 5-35. DOI: 10.1080/10609160302341

- Doering, Mary D. “Accessories, 1715-1785.” in Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Kaufmann, Miranda. Black Tudors: The Untold Story. London: Oneworld Publications, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083265546

- Levine, Adam, and Monique Johnson. “Investigating our mystery painting.” The Art Gallery of Ontario, 9 April 2020. Accessed 17 June 2020. https://ago.ca/agoinsider/investigating-our-mystery-painting

- Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., and Dan Lewandowski. The Complete Costume Dictionary. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1130805377

- “Posche (Unterkleidung (Damen)).” Germanisches Nationalmuseum. www.objektkatalog.gnm.de/objekt/T2479

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. New York: Fairchild Publications, 2004. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/869900091

- Vookles, Laura L. The Jeweler’s Eye: Nineteenth-Century Jewelry in the Collection of Nancy and Gilbert Levine. Yonkers, NY: Hudson River Museum, 1986. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/14242844

- Ward, Gerald W. R. The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. http://www.oxford-materialstechniques.com/?authstatuscode=202

- Whitacre, Janea. “Head Wear, Men’s and Women’s, 1715-1785.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699