A complex portrait of Louis XV’s daughter Marie-Adélaïde clinging to the old regime of France through fashion and decor just before the revolution.

About the Portrait

“One of the characteristics of Labille-Guiard is her virtuosity in the faithful rendering of the materials.”

In 1786, Labille-Guiard received the commission for a full length portrait of Marie-Adélaïde de France (1732-1800), also known as Madame Adélaïde, the daughter of the king. Labille-Guiard did a great deal of preparation to carry it out, including a pastel study of Madame Adélaïde’s face (Fig. 2). The sitter was in her fifties at this time, and we can compare her appearance with earlier portraits of her in her younger years, including a 1758 oil by Jean-Marc Nattier (Fig. 3). The oval frame next to her in this painting contains three heads in profile – the Dauphin (her brother), Marie Leczinska (her mother), and King Louis XV (her father) – and the words along the bottom say “leur image est encor le charme de ma vie” [their image is still the charm of my life].

Labille-Guiard received 5,000 francs for completing the portrait, which was displayed in the Paris Salon of 1787. She was later commissioned to paint portraits of others in the family, and her portrait of Madame Victorie, Madame Adélaïde’s sister, was shown at the Salon of 1789 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749-1803). Self-portrait, ca. 1774. Watercolor and gouache on ivory; 10.3 x 8.4 cm (4 x 3.3 in). Celle, Germany: Bomann-Museum. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Adelaide Labille-Guiard (French, 1749-1803). Marie-Adélaïde de France, 1786-1787. Pastel on two sheets of blue paper mounted on canvas; 73 x 58.8 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, INV.DESS 1159. Source: Chateau de Versailles

Fig. 3 - Jean-Marc Nattier (French, 1685-1766). Marie-Adélaïde of France making knots, 1756. Oil on canvas; 90 x 75.5 cm. Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, MV 3801. Source: Chateau de Versailles

Fig. 4 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749-1803). Victoire Louise Marie Thérèse de France, dite Madame Victoire, 1788. Oil on canvas; 271 x 165 cm (106.6 x 64.9 in). Versailles: Chateau de Versailles, INV 5244. Source: Joconde

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749–1803). Madame Adélaïde, 1787. Oil on canvas; 278.3 x 194 cm, Versailles: Château de Versailles, MV 3958. Source: Château de Versailles

About the Fashion

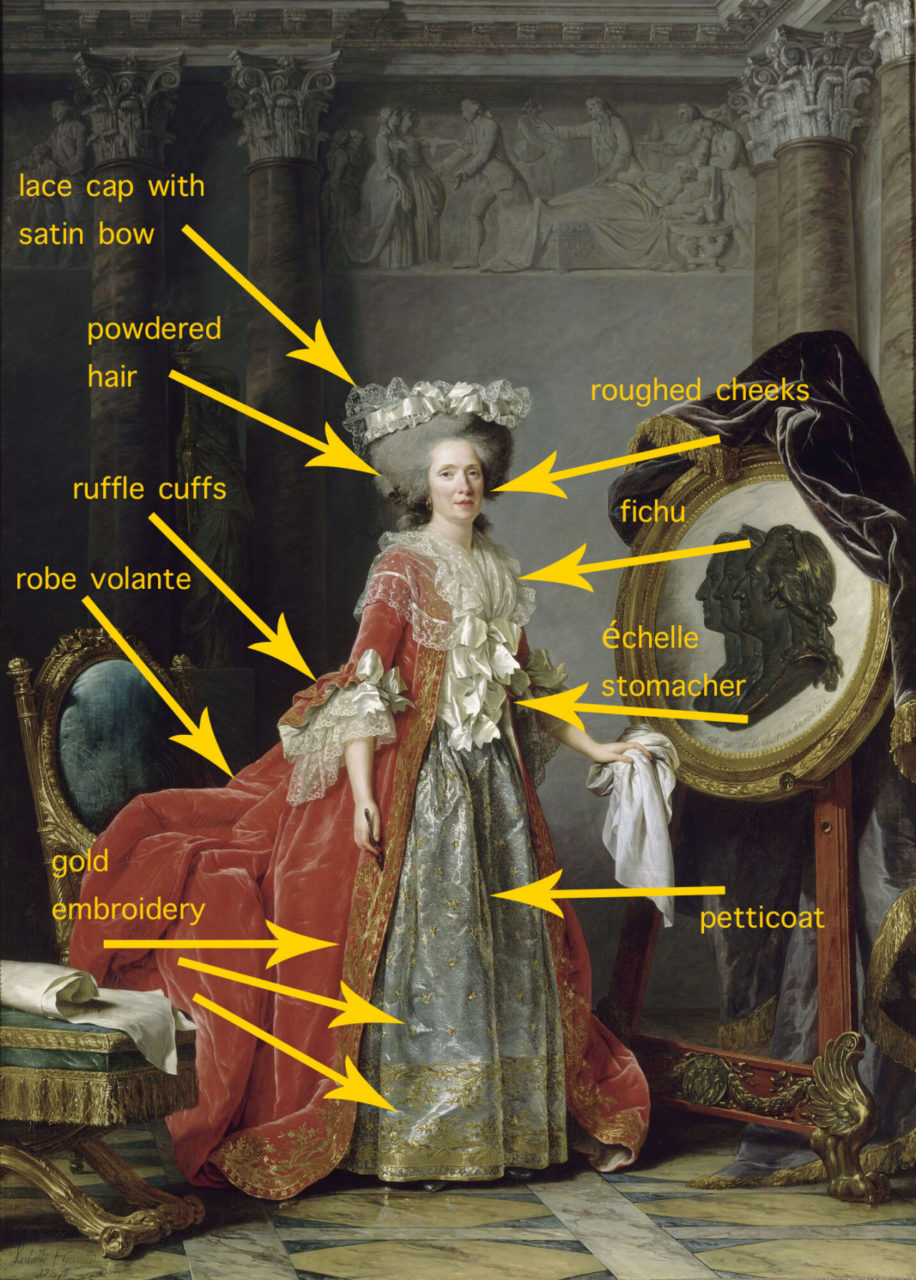

In this portrait we see Madame Adélaïde wearing a red velvet robe, probably à la française (Fig. 5), lined in white. It has delicate gold embroidery along the edges and while the arms are closely fitted, she has left the front edges loose and unpinned. Under the velvet robe we can see a cream silk satin stomacher decorated with rows of bows, called échelle (Fig. 6). Also showing is a silver satin petticoat with embroidered gold stars and a similar pattern of goldward edging to the dress. She is wearing a silk fichu around her neck and has elaborate lace engeagantes (sleeve ruffles), as well as a transparent cap with a wide satin ribbon over her frizzed and powdered hair. Peeking out from under her petticoat is a pair of silver shoes.

The paintbrush and rag in her hands imply that she is working on the triple portrait of her family members set up next to her. This would have been staged, as an artist would not paint in such a luxurious outfit. Additionally, in her memoirs courtier Madame Campan claims that the Mesdames, including Adélaïde, would quickly cover states of undress for daily visits by the king rather than dressing fully for the occasion:

“Mesdames put on an enormous hoop, which set out a petticoat ornamented with gold or embroidery; they fastened a long train round their waists, and concealed the undress of the rest of their clothing by a long cloak of black taffety which enveloped them up to the chin.” (Campan, ch. 1)

As the daughter of a king, Madame Adélaïde would naturally want to portray her wealth and status in a state portrait. Labille-Guiard does just that, demonstrating it through expensive fabrics and elaborate embroidery. But the robe à la française, as Phyllis Tortora explains in Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress (1998), was an outdated fashion by this time:

“After 1770, the robe à la Française modified, as paniers were replaced by hip pads. Excess fabric was pulled through pocket slits in such a way that the bunched fabric hung through the pocket to form a drapery. By 1780, this robe was no longer fashionable. The robe à l’Anglaise…persisted into the 1780s.” (240)

It continued to be worn at courts for formal occasions, though, and Madam Adélaïde was not entirely out of the fashionable moment, as we see from her hairstyle. That being said, the artist could have taken some artistic liberties on the red robe. This was common in the eighteenth century; artists would paint their sitters in fashions that did not exist. See the clothing in the portrait of Rebecca Boylston in figure 7, which bears no resemblance to real clothing at the time and features a similar red velvet robe. Like the française style, sumptuous fabrics like velvet had mostly gone somewhat out of fashion by the 1780s but continued to be used at court (Fig. 8) and in a few other occasions, though usually in anglaise or redingote styles (Fig. 9).

Despite the artistic liberties that may have been taken and the dated nature of the gown, this ensemble exudes wealth and status. The amount of expensive fabric she wears shows this easily, as does the goldwork embroidery around the edges of the dress and the petticoat and the lace at her cuffs.

“In the 18th century, complex metal thread embroidery was made in professional workshops, where embroiderers spent many years as apprentices… Metallic lace is made from metal threads such as gold, silver, or copper [and] France became renowned for gold lace production.” (Collinge 71)

There is metal-thread embroidery worked on the stomacher of the dress in figure 10 and further metal thread woven throughout the petticoat and worked into the lace trim. The fabric of Madame’s silver petticoat was probably very expensive even plain; having the gold stars embroidered make it something only the extraordinarily wealthy would be able to afford.

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (English). Woman's dress and Petticoat (Robe à la française), ca. 1760. Silk plain weave with weft-float patterning and silk with metallic-thread supplementary-weft patterning, and metallic lace. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, M.79.118a-b. Gift of Mrs. Henry Salvatori. Source: LACMA

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Stomacher, ca. 1775. Silk. Stockholm: Nordiskamuseet, NM.0186310A-C. Source: Digitaltmuseum

Fig. 7 - John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815). Rebecca Boylston, 1767. Oil on canvas; 127.95 x 102.23 cm. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 1976.667. Bequest of Barbara Boylston Bean. Source: Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (Mexican). Court dress, ca. 1785. Silk velvet, satin, spangles. Mexico City: National History Museum of Mexico. Source: Dressing the New World

Fig. 9 - Adélaïde Labille-Guiard (French, 1749-1803). Madame de Selve faisant de la musique est un tableau, 1787. Oil on canvas. New York: Private collection. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (British). Court dress, ca. 1750. Silk, metal thread. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.65.13.1a–c. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1965. Source: MMA

Fig. 11 - Adelaide Labille-Guiard (French, 1749-1803). Portrait of a Lady, ca. 1787. Oil on canvas; 100.6 x 81.4 cm. Quimper: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper, 873-1-787. Source: Musée des Beaux-Arts de Quimper

Madame Adélaïde is depicted wearing a sheer silk fichu, or kerchief, worn over the shoulders and tucked into her stomacher. In Costumes of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century (1970), Phillis Cunnington describes how the fichu was worn: “Towards the end of the century they were much larger and spread out over the shoulders like a shawl.” (95) We can see the same style worn with an updated dress in a contemporaneous Labille-Guiarde portrait in figure 12, inspired by peasant life but made fashionable when worn in expensive fabrics. Lace was handmade and took a great deal of time to create, making it very expensive. Susan North in 18th-century Fashion in Detail (2018) explains:

“Sleeve ruffles were an important accessory in women’s fashion, and many laces were made specifically in scalloped shapes of increasing size, to be worn together in twos or threes. These were sewn to the cuff of a women’s linen shift in order to be visible underneath the sleeve ruffles of a gown, mantua or sack.” (104)

Lastly, Madame Adélaïde is wearing a lace cap with a large satin bow on her hair, similar to her appearance in the pastel study that Labille-Guiard did before creating the painting (Fig. 2). As it was aesthetic rather than practical for this outfit, it is fragile and merely perched atop the head as a sign of status. The light grey color of her hair indicates the white powder covering her natural hair color for both hygiene and fashion purposes. Her hair matches the woman’s in figure 11; they both wear a highly fashionable afro-esque frizzed style, and it is the only part of Madame Adélaïde’s portrait that is genuinely in step with the fashion of the time.

This painting depicts an aging princess who, once fashionable, now clings to the trappings of courtly France and her ancestral heritage: gleaming silks, plush velvets, and gold-thead embroidery–a picture of wealth and status rather than intellectual or egalitarian ideals.

References:

- “Adélaïde Labille-Guiard Portrait de femme.” Musée des beaux-arts de la ville de Quimper. Accessed November 21, 2018. http://www.mbaq.fr/fr/nos-collections/ecole-francaise-des-17e-et-18e-siecles/adelaide-labille-guiard-portrait-de-femme-342.html.

- Campan, Henriette. Memoirs of the Court of Marie Antoinette, Queen of France. Boston: L.C. Page & Co., 1900. Project Gutenberg.

- Collinge, Annette. Flowers: Exquisite Needlework of the Embroiderers’ Guild Collection. Kent: Search Press Ltd, 2018. Worldcat.

- Cunnington, Phillis. Costumes of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century. Boston: Plays, inc, 1970. Worldcat.

- Nicholson, Kathleen. Labille-Guiard [Née Labille], Adélaïde. Oxford University Press, 2003. Oxford Art Online.

- North, Susan, and Henrietta Clare. 18th-Century Fashion in Detail. London: Thames & Hudson and the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A), 2018. Worldcat.

- Tortora, Phyllis, and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. New York: Fairchild Publications, 1998. Worldcat.