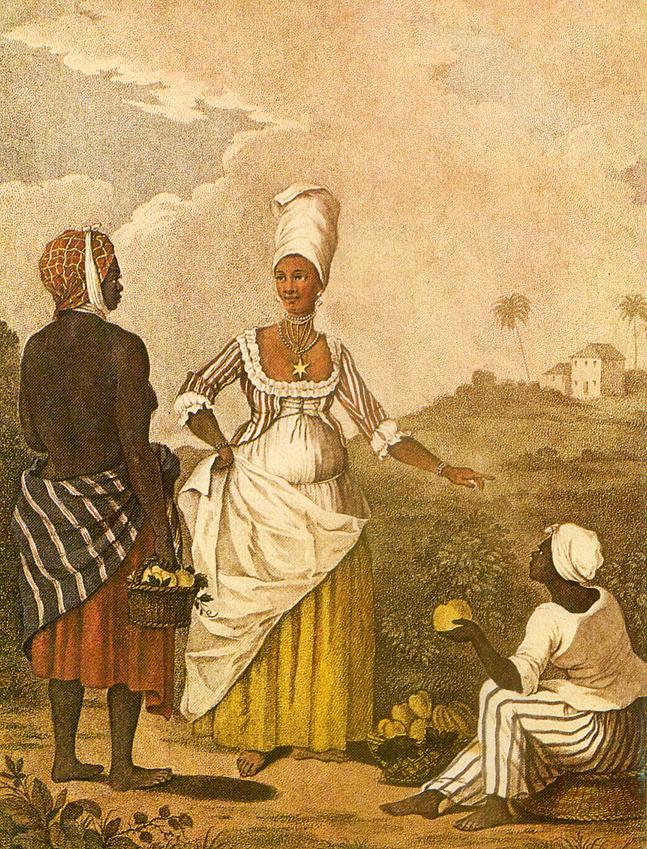

In a late 18th-century painting organized by skin tone, Agostino Brunias has depicted a range of colonial Dominican fashions from the wealthy elite to the poorest people whom they enslaved.

About the Portrait

This painting of Free Women of Color by Agostino Brunias (c.1730-1796) is a complicated and particularly European view into the daily life and social stratification of the mixed-race inhabitants of the Caribbean in the late eighteenth century.

Agostino Brunias was a Italian painter who worked on the islands of St. Vincent and Dominica after exhibiting paintings in Rome in the 1750s and in London at the Free Society of Artists in the 1760s (Grove; Mohammed 250). He arrived in the Caribbean in 1764 as the personal painter of William Young, who would become the first appointed British governor of Dominica, and transformed his style from intricate landscapes to everyday scenes in the style of genre painting (Fig. 1).

He has been called a “talented colorist” and historian Edward Sullivan describes this painting as “one of Brunias’ most appealing” pictures and seeming like “an outdoor fantasy promenade in the manner of Thomas Gainsborough” (Bagneris; Sullivan 18). While the Brooklyn Museum dates this painting c. 1770-96, the 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center has dated it c. 1764.

In the “Antilles, Lesser” entry for Grove Art Online (2003), Janet H. Momsen, et al. claim that Brunias is significant as a colonial artist:

“[Brunias’] paintings represent an important foundation of visual culture in the colonial Caribbean…The brightly patterned textiles depicted in Agostino Brunias’s market scenes on the island of Dominica attest to the symbolic importance these textiles had for free women of color who both sold and wore these fabrics as assertions of their freedom.”

The Caribbean was central to the British empire and economy in the 18th century, as sugar, coffee, and enslaved people were traded and exported (Morgan 54-55). Brunias’ paintings of life there were turned into engravings and published in both England and France in the 1790s and early 19th century (Bagneris; Mohammed 252). Before that, several of his Caribbean paintings were exhibited at the prestigious Royal Academy in England in the 1770s; he also published a series of prints based on them in 1779 (Figure 2) (Kriz 351).

The Brooklyn Museum says of the painting:

“[O]n the grounds of a Caribbean sugar plantation, two luxuriously dressed mixed-race sisters enjoy a walk with their mother, children, and eight African servants….Although Brunias was originally commissioned to promote upper-class plantation life, his paintings soon exposed the artificialities of the region’s racial hierarchies.”

Brunias romanticized the colonial society and economy of the Caribbean for his rich white patrons. He painted free and enslaved men and women of color in nature and in markets, at work and in leisure, creating a fantastical vision of peace and harmony and organization enabled by the colonial machine (Figure 3). Paintings like these soothed white European fears of class mixing and the breakdown of social stratification in the colonies, as each person is neatly defined by their appearance and a hierarchy of skin color is obvious (Kriz 209). This was almost certainly not the lived reality of the painting’s subjects, if they were real at all.

At its core, this painting – likely set in Dominica – is about categorization (Bagneris). From foreground to background, the women’s skin colors become darker and their clothes less fine. The children wear clothing physically linking them to adults of the same skin color. Brunias titled paintings like this according to the racial identities of the people depicted, which historian Beth Fowkes Tobin attributes to the paintings’ purpose as “taxonomic images of specimens, not representations of individuals” (139) (Fig. 4). Brunias’s work is similar in spirit to the casta painting tradition of South America, and this painting is named likewise (Sullivan 18).

Historian Patricia Mohammed suggests that even though there may be some accuracy in the “sense of gender, class and race relations that typified the evolution of creole society” in these paintings, it’s likely that they were heavily influenced by European sensibilities and artistic tastes, transposed onto Caribbean life (255).

In her chapter “Marketing Mulatresses in the Paintings and Prints of Agostino Brunias,” (2005), historian Kay Dian Kriz explains:

“Brunias attempted to promote these newly-won colonies as a place where people, as well as raw materials, could be cultivated and refined… Within the context of a nascent abolitionist movement, successfully promoting these islands through art had to involve demonstrating the happiness and well-being of the slaves who lived there.” (196)

Even though these paintings represent a colonialist fantasy, many historians continue to value them as unusual examples of people of color depicted in European painting from this time period and therefore consider them an “important record” (Mohammed 254). Their surroundings and clothing are probably decently accurate, and Brunias does not mock his subjects, most of whom are people of color, or place them only in subservient positions. However, they remain a far cry from the dignified portraiture of real people like that of the unidentified woman in figure 6 [read our essay about her here!] or the self-portrait of mixed-race painter José Campeche y Jordán (Fig. 7), who was the son of a formerly enslaved man and working in Puerto Rico during this time (Benezit).

Fig. 1 - Agostino Brunias (Italian, 1728-1796). Linen Market, Dominica, ca. 1780. Oil on canvas; 49.8 x 68.6 cm (19 5/8 x 27 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.76. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 2 - Agostino Brunias (after) (Italian, c.1730-96). The Barbadoes Mulatto Girl, 1779. Print. Bridgetown: Barbados Museum & Historical Society. Source: Utah State University

Fig. 3 - Agostino Brunias (Italian, c. 1730-1796). Dancing Scene in the West Indies, ca. 1764–96. Oil paint on canvas; 50.8 × 66 cm. London: Tate, T13869. Purchased with assistance from Tate Patrons and Tate Members 2013. Source: Tate

Fig. 4 - Agostino Brunias (Italian, c. 1730-1796). Free West Indian Dominicans, ca. 1770. Oil on canvas; 31.8 x 24.8 cm (12 1/2 x 9 3/4 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.74. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 5 - Agostino Brunias (Italian, c. 1730-1796). A Mother with her Son and a Pony, ca. 1775. Oil on canvas; 33 x 27.9 cm (13 x 11 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B2009.12.1. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown. Untitled, ca. 1775. Oil on canvas; 80 × 56.2 cm (31 1/2 × 22 1/8 in). Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, 2019/2437. Purchase, with funds from the European Curatorial Committee, 2020. Source: AGO

Fig. 7 - José Campeche y Jordán (Puerto Rican, 1751–1809). Self-portrait, ca. 1800. Oil on canvas; 92 x 64.5 cm (36.2 x 25.3 in). Private Collection. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Agostino Brunias (Italian, ca. 1730-1796). Free Women of Color with their Children and Servants in a Landscape, c.1770-96. Oil on canvas; 50.8 x 66.4 cm (20 x 26 1/8 in). Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 2010.59. Gift of Mrs. Carll H. de Silver in memory of her husband, by exchange and gift of George S. Hellman, by exchange. Source: Brooklyn Museum

About the Fashion

The clothing worn in European colonies, which in Dominica would have been a mixture of indigenous Kalinago, African, and European styles, has not been examined as thoroughly as costume in Europe and is thus more difficult to analyse. Beyond the fashions that came from cultural mixing, colonial aesthetics were also often somewhat different than English modes due to sheer distance and hotter environments (Shrimpton 55). That means that we have to analyze this image by looking at similar paintings from the same time and place – English paintings won’t help very much.

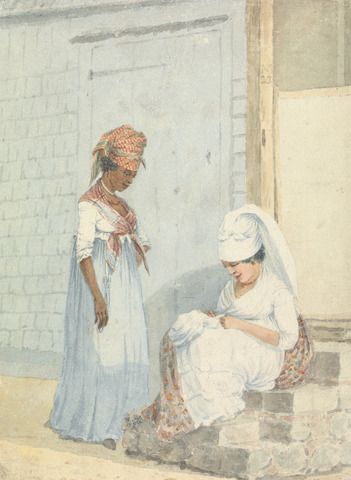

Creole fashion likely changed quite a bit in the thirty years that Brunias painted, even though his depictions of clothes rarely do. See figure 8, of two seamstresses on St. Kitts in the 1790s; their dress silhouettes are similar to the fashions in Europe during that time, and are quite different to Brunias’ later pictures. He also tended to paints the same clothing, figures, and backgrounds in different communities, islands, and decades, indicating that he was not accurately representing the people of Dominica (Kriz 197).

Contemporary French artists Savart and Le Masurier, working respectively on the islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique, show less variation in clothing textiles and silhouettes across scenes (Fig. 9). Brunias seems to have liked painting stripes and may have over-represented striped textiles and sheer variety where plain white cotton and linen were more often worn (Lafont 140).

Historian Anne Lafont notes that European painters of Caribbean scenes “used textiles as an extension of human diversity based on skin color” and that fabric pattern was the easiest way for them to ornament and beautify the inhabitants (137-8). Brunias and others racialized nudity in the same way as well; only Black and Indigenous figures with darker skin tones are nude or close to it (Lafont 129).

What that means is that we have to take these paintings with a grain of salt – much of the clothing might be made up, or borrowed from other years and islands.

The Men

The three men in this painting wear almost identical clothing. Their uniforms, seen also on the little boys, indicate that they were servants or enslaved men who would be seen by the public in close confines with the family. Such servants were expected to be dressed appropriately to demonstrate the family’s wealth and propriety (Waterfield 12).

Matching uniforms, however intricate, were a badge of servitude. Even if these men and boys were not enslaved, their clothes mark their lower status. In her article “Livery” (2015), Patricia Hunt-Hurst describes:

“The livery tradition began in Europe, and the practice continued in America during the late 18th century… Features were included such as good-quality wool in two contrasting colors that represent the family’s coat of arms.” (2:173)

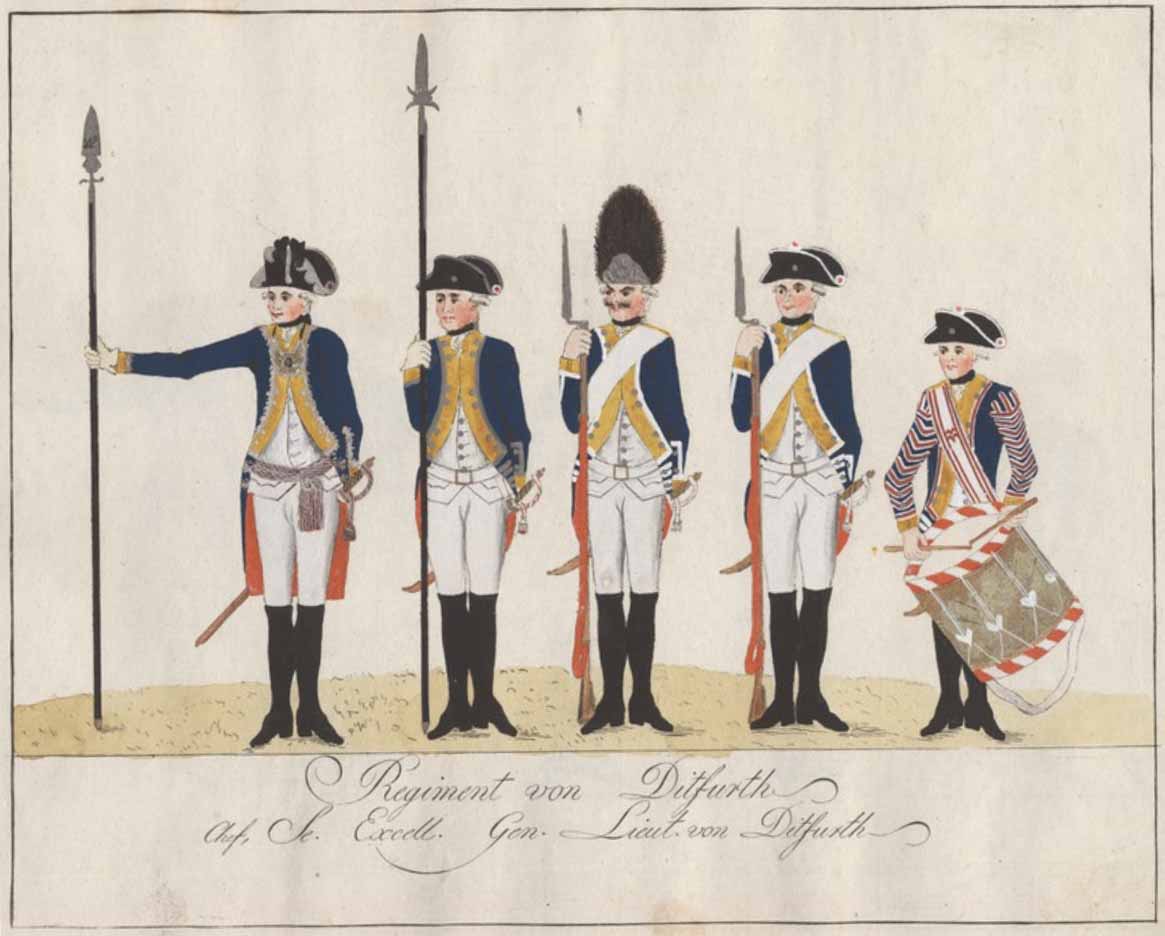

This practice spread to many European colonies in the 18th century; figure 10 shows footmen in Brazil wearing livery in the 1770s. The uniforms are distinctly military-inspired with their folded-back facings and epaulettes; they seem to be livery versions of the Hessian regiment in figure 11. They may have been designed that way because of the Antilles’ frequent exposure to British and British-allied soldiers (Fig. 12).

The men may be footmen and the boys pages. Young enslaved boys were seen primarily as decorative objects in the wealthiest of households (Fig. 13) (Waterfield 141). But while Brunias’ depicted entourage is surely wealthy, they are either not at the top of the heap or they simply did not care to stay en vogue in the European styles. See figure 14 of the family of the French governor of Martinique; they are somewhat out of touch with the heights of French fashion but are still clearly dressing according to it.

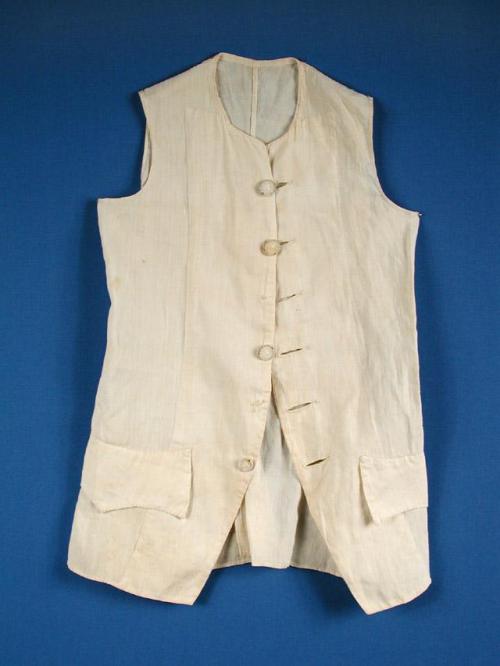

The footmen’s uniforms consist of a white waistcoat (Fig. 15) and pair of breeches, a black and silver hat, and a blue and yellow frock coat. Anything white in this painting is likely to have been linen, which is far more tolerable in hot weather than other natural fibers. Fine white linen suits were popular in the Americas to deal with the weather, but enslaved people were generally forced to wear rough, hardy textiles. In her article “African American Clothing, 1776-1819,” (2016) Patricia Hunt-Hurst describes that:

“Most clothing [for enslaved people] was made out of coarse, inexpensive cloth such as osnaburg, ‘jeans,’ homespun, and a plain-weave white cotton or wool fabric advertised as ‘Negro cloth’… made to last for several months of regular wear.” (2:33)

All are wearing shirts, probably linen or a blend, under their waistcoats; one can be seen on the toddler in the background as well. The men are also wearing stocks for fashion and cleanliness, and the black stock on the man in the center is one of the few pieces of individuality in these ensembles. Usually they would be of plain white linen (Fig. 16).

In her article “Neckwear, 1776-1819,” (2016), Patricia Hunt-Hurst notes:

“In the beginning of the federal era… White linen and silk neck cloths were worn; some wore worn with frills or ruffles that decorated the front of the shirt. By the 1770s the stock, a plain linen band that fastened at the back, was worn underneath the shirt collar, which was turned down over it.” (1:198)

Black stocks were worn in the military and occasionally by civilians, and they could be of fabric or leather (Cumming 131). The boys are not wearing stocks, but instead black silk ribbons that are used to close their shirt collars, which is often seen in portraiture on boys between the ages of four and twelve (Fig. 17).

The boy in yellow wears an individual coat and set of breeches in a striped fabric, either silk or linen (Fig. 18). The cut of the coat and waistcoat, if up to date, suggest that this painting was done before 1780. The boy also has knitted stockings and black leather shoes on, bowing to European propriety – in this image, a sure sign of status and another method of clear visual difference between the two Black boys at right.

The smallest boy and two of the men also wear cocked hats (Fig. 17, known today as ‘tricornes’), and the last man and both boys wear military-style caps with large metal cap plates (Fig. 19). All of these hats were likely blocked wool felt, and the silver edging on the cocked versions was called ‘lace’ (Cumming 118).

One of the boys holds a walking stick. They were common amongst both men and women in England, but were more likely to have been carried by a wealthy boy than a boy that his family enslaved. Brunias may be asking the viewer to think about the painting’s occupants and decide that the boy in yellow was tired of carrying his little gentleman’s walking stick.

Fig. 8 - William Kay. Seamstresses, St. Kitts, Carribean, 1798. Watercolor over graphite on cream wove paper; 16.8 × 12.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 7/8 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.2639. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 9 - Marius-Pierre Le Masurier (French, active 1769-75). Marché à Saint Pierre de la Martinique, 1775. Oil on canvas; 162 x 227.5 cm (63.7 x 89.5 in). Avignon: Musée Calvet, 23.623. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 10 - Carlos Juliao (Italian, 1740-1811). Carrying a Sedan Chair (Palanquin), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1770s. Rio de Jañiero: National Library of Brazil. Source: Slavery Images

Fig. 11 - J.H. Carl. Regiment fon Ditfurth, 1784. Print; 22.7 x 34.5 cm. Providence: Brown University Library, 249634. Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection. Source: BDR

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (British). Full dress frock coat of a Navy Captain, ca. 1774. Wool, linen, horn, brass, gold alloy; overall: 102.5 x 60 cm. Royal Museums Greenwich, UNI0011. Source: RMG

Fig. 13 - Isaac Lodewijk la Fargue van Nieuwland (Dutch, 1726 – 1805). A servant, presumably Cupid, 1766. Paper and ink; 39.2 × 26.4 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, RP-T-00-3549. Source: Rijksmuseum

Fig. 14 - Le Masurier (French). Portrait de la famille de Choiseul-Meuse, ca. 1775. Painting. Bordeaux: Musée d'Aquitaine. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (American). Boy's waistcoat, 1770s. Hand-stitched linen; 43.2 x 38.4 cm (17 x 15 1/8 in). Hartford: Connecticut Historical Society, 2001.49.6. Gift of Annetta Eddy Brigham. Source: CHS

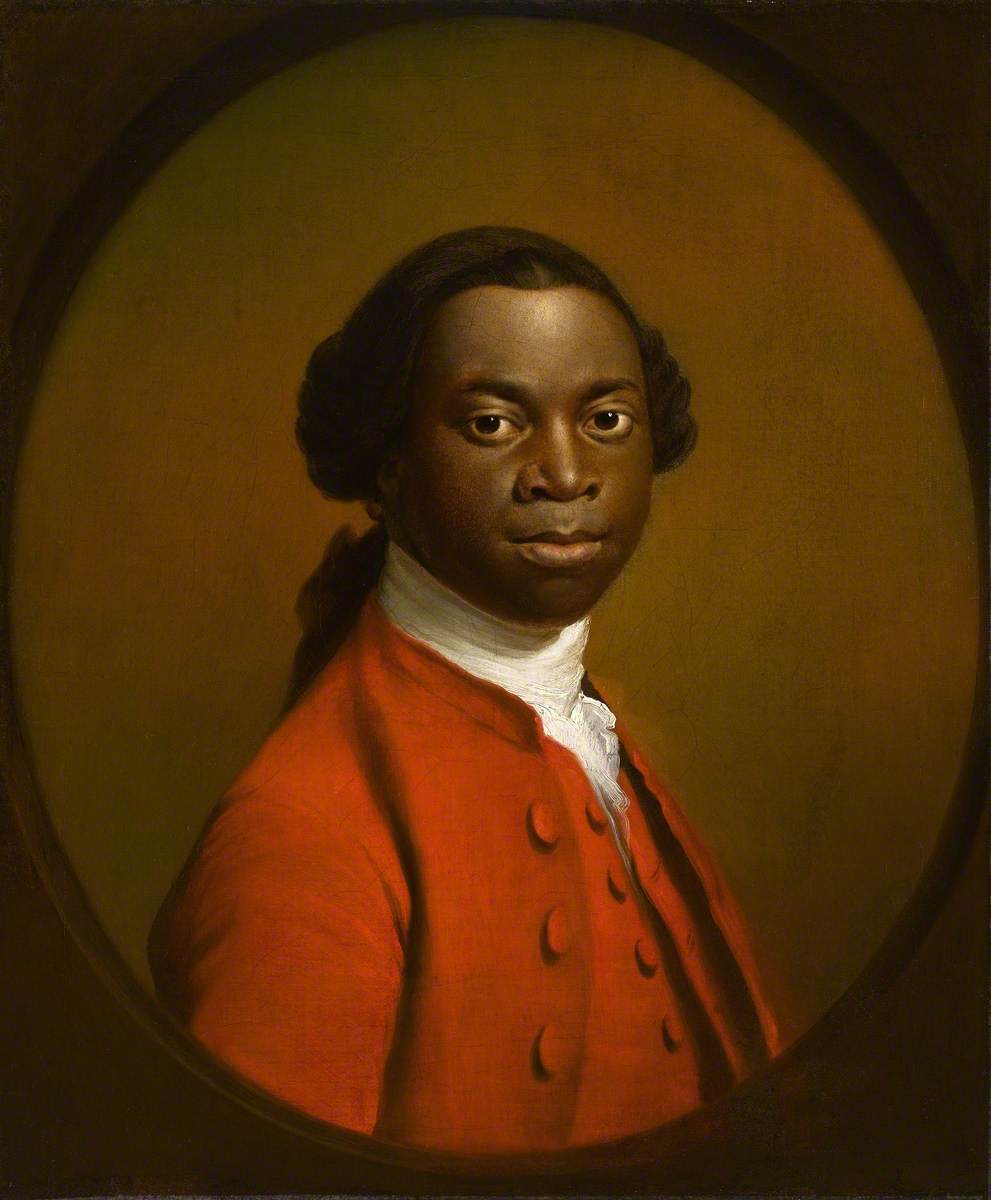

Fig. 16 - Allan Ramsay (attr.) (British, 1713–1784). Portrait of an African, ca. 1780 (attr. ca. 1757-60). Oil on canvas; 61.8 x 51.5 cm. Exeter: Royal Albert Memorial Museum, 14/1943. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 17 - Philip Mercier (German (active England), c.1689 - 1760). A young drummer boy, before 1761. Oil on canvas; 76.2 x 63.5 cm (30 x 25 in). London: Christie's, 2003, Live Auction 6730: British Pictures 1500-1850 (Lot 29). Source: Christie's

Fig. 18 - Designer unknown (British). Boy's breeches, ca. 1760. Striped silk/cotton blend. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.113-1953. Source: VAM

Fig. 19 - Designer unknown (British). British musician cap plate, ca. 1780. Metal. Washington, DC: American Revolution Institute, M.1994.006. The Robert Charles Lawrence Fergusson Collection. Source: ARI

The Women

Wealthy women’s fashion in England around 1770 (Fig. 20) was markedly different from the clothing we see in Brunias’ art. Silks, conical stays, side hoops, and puffed, rounded hair were integral to the courtly look. But the clothing of the English working class (Fig. 21) also differed greatly from Caribbean dress, as the differences weren’t only formality and fabric type but also patterns and silhouettes. The clothing Brunias paints is in some ways more similar to the clothing worn in other rural areas of Europe; see the Finnish woman in figure 22.

Brunias paints as if the fashionable waistline had migrated entirely. The Creole women wear gowns that show off their natural shapes and protect their hair with intricate head-wraps that are often more complex than the rest of their clothing. While light-skinned planters’ wives are shown wearing the European silhouette (Fig. 23), many of the other free women of color abstain. The Dominican silhouette was instead wider and more rounded, as breasts were allowed to sit naturally and skirts were tied artfully at the hips instead of the natural waistline. Skirts on working women also averaged longer than the European styles (Fig. 24), and there are multiple varieties of bodices and bodice silhouettes, some of which are visible in this painting.

Some of the women may be wearing jumps, the unboned version of stays, but many are clearly not wearing anything at all for support. If accurate, this may be due to a mix of social status and weather-appropriate dress. Enslaved women were rarely provided stays, and the heat made extra layers a burden. However, Savart and Le Masurier invariably depict the more heavily-dressed women in their scenes wearing stays (Fig. 25), so this might be an idiosyncrasy of Brunias’.

Women in a Caribbean climate would have worn linens and cottons in light colors in order to deal with the hot, humid climate. As with the men, enslaved women probably wore osnaburg or similar. Printed cottons were probably relatively rare compared to woven linens and solid cotton muslin. The latter was so popular that it was eventually taken up in Europe; the plain white robe en chemise became the subject of much controversy when a portrait of the French Queen Marie-Antoinette in one was exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1783 (Fig. 26) (Rauser).

Their headwraps were also iconic of the Caribbean. The Met writes:

“A distinctive Creole style developed in the region as European fashions were integrated with African modes such as the head wrap, worn by nearly all women regardless of race or social status.”

Headwraps, often done with colorful Madras-made cottons, were the most important accessory for any African-descended woman of color. Typically, they were also later appropriated by white women (Rauser). The “superb” hats worn by Creole fashionistas also may have inspired Parisian Merveilleuses and Incroyables (Lafont 138).

There are two different styles of gown visible in this painting: short gowns and more formal close-bodied gowns (either pleated-back or quartered; we can’t see the back to distinguish). The darker-skinned women to the left are wearing short gowns that close with ties and pins and gather under their busts.

In José Blanco F.’s encyclopedia Clothing and Fashion (2016), a short gown (Fig. 27) is defined as a:

“long-sleeved bodice with a front opening and a peplum below the waist that was made from one piece of fabric so that the sleeves were cut in one with the bodice and there was no shoulder seam. Sometimes these garments were fitted to the body with pleats or drawstrings…. and is considered an informal or working-class garment” (1:343).

Many enslaved people in the Caribbean were given only a linen shirt or shift to wear while working, though, and Brunias does paint free women of color wearing short gowns, so these women might not necessarily be enslaved. (Compare them to the woman at the far left with the toddler, who definitely was.) Patricia Hunt-Hurst describes that:

“Women working in the fields would wear a short gown and skirt of coarse, inexpensive cloth. The skirt would be full, as was typical of the period, and would generally be shorter in length than what the house servants would wear.” (2:34)

The lighter-skinned women are wearing open gowns (meaning the petticoat is exposed at center front) that are designed to have a gap in the front and close over a stomacher or other under-layer. Two of them have bodices that close with spiral lacing (see figure 28 for a European example) and the woman at right appears to have a compères front, which was a stomacher permanently sewn in that opened center-front with buttons (Fig. 29) (Blanco 345). Both of these styles of dress closure were relatively rare in Europe, and the open centers point to an earlier date just as the men’s clothes do.

All of these gowns have some ruffled self-trim at the cuffs, and the white one appears to have boning at the opening to keep it straight and looking more European. All of the women depicted are wearing long petticoats and aprons tied at their hips, with the bow coming around the front, and all but left-most woman appear to be wearing chemises underneath. The lighter-skinned women wear neckerchiefs (fichus), which would have served to protect them from the sun. The chemises, fichus, aprons, and headwraps were likely all made of linen, which wicks away sweat better than cotton.

All of the women whose necks are visible are wearing pearls and matching necklaces and earrings and bracelets. While this may have only been an artistic reflection of Caribbean as a pearl center, it seems likely to have been accurate. In the seventeenth century, Spanish writers observed that “now everyone wears pearls and seed pearls, men and women, rich and poor….” and “even black women wear strands of them” (Warsh 81).

During this time, various island governments passed sumptuary laws, which restricted forms of dress and adornment. In 1784, for example, the high court of Santo Domingo issued an edict criminalizing the wearing of pearls, gemstones, gold, or silver, in dress and as accessories by free people of color (Johnson 198). This tells us that free people of color had been wearing such things, and that those in power felt threatened by their luxurious appearances. It is entirely possible that Brunias commonly saw women of a variety of social standings wearing sets of pearls like these.

How fashionable were these outfits? Without a specific date and a larger body of comparisons, it’s hard to tell. We can presume via the painting’s composition that the light-skinned women are at least relatively fashionable. Brunias described a pair of women in a painting dated ca. 1780 as wearing “elegant dress” (Fig. 30), but their bodices and sleeves are cut differently, and they wear colorful neckerchiefs. Perhaps that is the difference that ten or more years made!

It is true that the women in this painting are wearing relatively simple clothes in comparison to what would have been worn in wealthy society in England. Their lack of stays indicates that they are probably not of the wealthiest class of people on colonial Dominica, but Brunias might expect us to have assumed that because of their skin color. The three central figures in this painting are free women of color who likely lived a life of not enormous wealth but relative leisure. The two women behind them might have been either free or enslaved, but did not have the resources to purchase and wear the ornate and colorful head-wraps that are seen in other Brunias paintings. Instead, they accessorized through simpler colored textiles and jewelry. The woman at far left was clearly the most restricted, and her basic white linen clothing and lack of undergarments tells us that she was enslaved.

This painting is a story of categorization and restriction, a European fantasy of life in a colonial society organized neatly by skin color – but it also reveals many ways that Caribbean fashion was markedly different from the styles in England.

Fig. 20 - Artist unknown (British). Mrs. Cadoux, ca. 1770. Oil on canvas; 212.7 × 135.9 cm. London: Tate, N03728. Bequeathed by Miss Mary Burgess Hudson 1931. Source: Tate

Fig. 21 - George Stubbs (British, 1724–1806). The Haymakers, 1785. Oil paint on wood; 89.5 × 135.3 cm. London: Tate Britain, T02256. Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery, the Art Fund, the Pilgrim Trust and subscribers, 1977. Source: Tate

Fig. 22 - Nils Schillmark (Swedish (active Finland), 1745-1804). Mansikkatyttö (Strawberry Girl ), 1782. Oil on canvas; 92 x 70 cm (36.2 x 27.5 in). Helsinki: Finnish National Gallery, A IV 3771. Source: FNG

Fig. 23 - Agostino Brunias (Italian, c.1730-1796). Planter and His Wife, with a Servant, ca. 1780. Oil on canvas; 30.5 x 24.8 cm. New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.81. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 24 - James Bretherton (c. 1730-1806) after Henry William Bunbury (British, 1750–1811). A Maid, 1774. Print; 27.8 x 18.1 cm (10 15/16 x 7 1/8 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1977.14.11163. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

Fig. 25 - Marie-Joseph-Hyacinthe Savart (French, 1735-1801). Quatre femmes créoles, 1770. Pastel. Pointe-à-Pitre: Musée Schœlcher de la Guadeloupe. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 26 - Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Le Brun (French, 1755–1842). Marie Antoinette in a Chemise dress, 1783. Oil on canvas; 89.8 × 72 cm (35 3/8 × 28 3/8 in). Langen: Hessische Hausstiftung. Source: MMA

Fig. 27 - Designer unknown (Swedish). Short gown, 1750-1775. Linen-wool blend; overall 63 cm. Oslo: Nordiskamuseet, NM.0090398. Source: Digitaltmuseum

Fig. 28 - Michel Pierre Hubert Descours (French, 1741–1814). Portrait of Elizabeth de la Vallée de la Roche, 1771. Oil on canvas; 80 x 63.7 cm. Barnard Castle: Bowes Museum, B.M.547. Bequeathed by the Founders, 1885. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 29 - Designer unknown (Probably Dutch). Fitted gown (Robe ajustée), ca. 1760. Silk. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, 1026484. long-term loan 1936. Source: ModeMuze

Fig. 30 - Agostino Brunias (Italian, c. 1730-1796). Free West Indian Creoles in Elegant dress, ca. 1780. Oil on canvas; 31.8 x 24.8 cm (12 1/2 x 9 3/4 in). New Haven: Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.79. Paul Mellon Collection. Source: YCBA

References

- 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center. “Slavery – The West Indies.” Scribd. https://www.scribd.com/document/256584437/Slavery-The-West-Indies

- Bagneris, Mia L. Colouring the Caribbean: Race and the Art of Agostino Brunias. Manchester : Manchester University Press, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/991315916

- “Campeche, José.” Benezit Dictionary of Artists.

31 Oct. 2011; Accessed 21 Jan. 2021. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/benezit/view/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.001.0001/acref-9780199773787-e-00031066 [subscription required] - Cumming, Valerie, Phillis Cunnington, and C. Willett Cunnington. The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/751449764

- Figes, Lydia. “Agostino Brunias and depicting people of colour in the colonial Caribbean.” ArtUK, The Public Catalogue Foundation, 25 July 2019. https://artuk.org/discover/stories/agostino-brunias-and-depicting-people-of-colour-in-the-colonial-caribbean

- Hunt-Hurst, Patricia. “African American Clothing, 1785-1819.” in Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- “Livery.”

- “Neckwear, 1776-1819.”

- Johnson, Jessica Marie. Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World. Philadelphia, PA : University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1142931199

- Kriz, Kay Dian. “Marketing Mulatresses in the Paintings and Prints of Agostino Brunias” in The Global Eighteenth Century. Nussbaum, Felicity, ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/826442343

- Lafont, Anne. “Fabric, Skin, Color: Picturing Antilles’ Markets as an Inventory of Human Diversity.” Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 43:2 (July-Dec 2016), 121-154. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1271/127146460005.pdf

- The Met. “Linen Day, Roseau, Dominica – A Market Scene.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/21113

- Mohammed, Patricia. “The Emergence of a Caribbean Iconography in the Evolution of Identity” in New Caribbean Thought: A Reader, 232-264, Meeks, Brian, and Folke Lindahl, eds. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/469341953

- Momsen, Janet Henshall, C. C. McKee, C. J. M. R. Gullick, John Newel Lewis, and Alissandra Cummins. “Antilles, Lesser.” Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 19 Jan. 2021. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:3117/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000003190 [subscription required]

- Morgan, Kenneth. Slavery, Atlantic Trade and the British Economy, 1660-1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/939868772

- Rauser, Amelia. “Madras and Muslin Meet Europe: On neoclassical cultural appropriation.” Lapham’s Quarterly, 18 March 2020. https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/madras-and-muslin-meet-europe

- Shrimpton, Jayne. “Dressing for a Tropical Climate: The Role of Native Fabrics in Fashionable Dress in Early Colonial India.” Textile History 23:1 (1992): 55-70. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1179/004049692793712430 [subscription required]

- Sullivan, Edward J. From San Juan to Paris and Back: Francisco Oller and Caribbean Art in the Era of Impressionism. New Haven, Conn: Yale Univ. Press, 2014. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/898435222

- Tobin, Beth Fowkes. Picturing Imperial Power: Colonial Subjects in Eighteenth-Century British Painting. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/469504512

- Warsh, Molly A. American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire, 1492-1700. Williamsburg, VA: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture; Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1004535853

- Waterfield, Giles, Anne French, and Matthew Craske. Below Stairs: 400 Years of Servants’ Portraits. London: National Portrait Gallery Publ, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/834455426