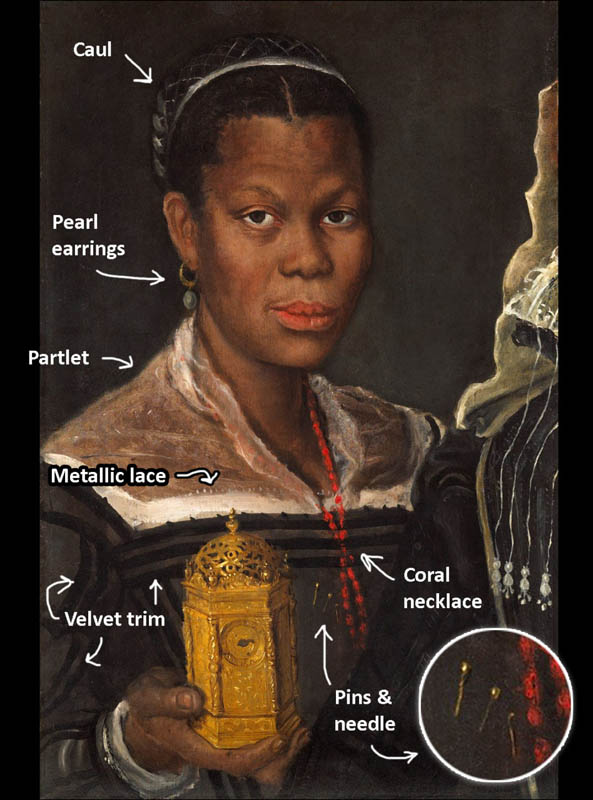

This 16th-century portrait attributed to Annibale Carracci is valuable for its realistic depiction of a Black sitter, possibly a seamstress, who is dressed in a fine but sensible black day dress with touches of Italian luxury.

About the Portrait

This portrait of an elegant woman in a black dress is a fragment of a painting which originally may have been twice as large, but was damaged and cut down (Tomasso). It was painted around 1583 or 1585 and is attributed to Italian artist Annibale Carracci (Fig. 1); if true, then he would have painted this in his early twenties. He came from an artistic family and was born in and worked in the city of Bologna until 1595. His early work consists of genre paintings and portraits like this one, but it is his later religious work, like the example in figure 2, for which he became famous (Barton).

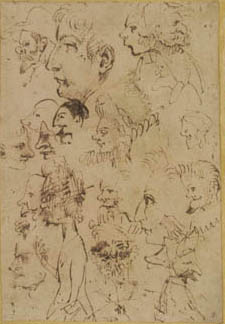

He is considered one of the greatest painters of his generation, one of the founders of the Baroque art style, and is cited as a forefather of sketch caricature (Fig. 3) (Barton). In his paintings, he cultivated a style of “broken brushwork…to represent the effects of light on form” which “gave his pictures an extraordinary sense of intimacy and immediacy” (Tomasso).

Mentions of this portrait in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century historical records refer to it as a “portrait of a black woman holding a clock” (Walters 130, Tomasso). At some point more recently, the sitter – a woman with dark hair, medium-dark skin, and dark eyes – was relabeled an “African Slave” and “African Woman.” Perhaps neither of these titles are true: while she may have been born in Africa and enslaved by the woman to her left, it is possible that she may have been born in (and raised free in) Italy. Perhaps she is a domestic servant, or runs her own business. She may even be related to the other sitter, of whom only a tiny bit of dress, ruff, and veil are visible. In her article “Free Men and Women of African Ancestry in Renaissance Europe” in Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe (2014), Joaneath Spicer says:

“While it was not unknown in the Renaissance for a European nobleman to marry an African woman and bring her to Europe, children of African descent born in European noble households were usually the offspring of exploitive relationships involving a slave, as in the case of…the most prominent European of the time now widely believed to be of African ancestry, Alessandro de’ Medici, duke of Florence.” (Fig. 4) (Walker 89)

Owners of this painting three and four hundred years ago did not see the sitter and think ‘African’ or ‘slave’: they simply saw a Black woman, and left the title at that. But who is she?

Every piece of a person’s wardrobe and setting was carefully planned in a portrait like this (Currie, 5.1). Thus, we cannot disregard the two pins and a needle stuck into the front of her bodice. Some have posited that the sitter is a dressmaker – a skilled job that required training from a master (Kaufmann 2013). While some Black men were able to start their own weaving and needle-making businesses in England around this time, the ability of a Black woman to do so in Italy is less certain (Kaufmann 2017, 121). Women could become weavers, but their success depended on location: weaving in Venice was male-dominated, but in Florence most weavers were women (Tinagli 112, Honeyman 613). Women were forced out of trades jobs en masse in many cities in the sixteenth century and relegated to what was seen as ‘unskilled’ labor, which was poorly paid and irregular in comparison to positions which they had once held (Honeyman 610). Plying one’s craft in domestic service was a feasible alternative.

This sitter’s needle and pins signify that she has skills dealing with needle and thread. While it is tempting to imagine that she designed and made her own clothing, dressmaking was a trade kept by guilds and restricted to men during this time (Crawford 35). It is more likely that she made accessories, like partlets and veils, or underwear, like camicias (shifts). It is also possible that she was responsible for re-trimming gowns in the household as trends changed, as a milliner in 18th-century France would have.

In comparison to archetypal portraits of idealized beauties, “portraits of ‘real’ women in [16th century] Venetian art are rare” (Tinagli 103). That makes this portrait all the more valuable, for its sitter is a member of the working class and undoubtedly had small impacts on thousands of lives while she lived her own, unlike the wealthy, isolated women normally portrayed, or imaginary villagers in genre scenes. This painting’s function is not to represent idealized womanhood and luxury, but to immortalize a woman who played a tangible part in society, akin to the active self-portrait of artist Sofonisba Anguissola (Fig. 5).

There are few other portraits depicting Black people in European fashions in such great detail from this period (Fig. 6 – read an analysis of it here!). Despite the care taken here in portraying a Black person, though, the arm of the woman next to her still cuts across her body and obscures her from coming fully into view.

Fig. 1 - Annibale Carracci (Italian, 1560-1609). Self-Portrait in Profile, 1590s. Florence: Galleria degli Uffizi. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2 - Annibale Carracci (Italian, 1560-1609). The Loves of the Gods, 1597-1608. Fresco; 2014 × 659 cm. Rome: Palazzo Farnese. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Annibale Carracci (Italian, 1560-1609). A series of caricature heads in profile, 1575-1609. Paper, ink; 20.1 x 13.9 cm. London: The British Museum, Pp,3.17. Source: TBM

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (after Girolamo Machietti) (Italian, 1535-1592). Alessandro de’ Medici, Duke of Florence (1530–37), after 1585. Tempera on canvas; 120 × 96 cm. Florence: Galleria degli Uffizi. Source: AKG Images

Fig. 5 - Sofonisba Anguissola (Italian, c.1532-1625). Self-portrait at the Easel Painting a Devotional Panel, 1556. Oil on canvas; 66 x 57 cm (25.9 x 22.4 in). Poland: Łańcut Castle, RKD.nl 204664. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 6 - Jan Jansz Mostaert (Dutch, c. 1475-1552/1553). Portrait of an African Man (possibly Christophle le More), ca. 1525-30. Oil on panel; 30 x 20.3 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, SK-A-4986. Source: Rijksmuseum

Annibale Carracci (attributed) (Italian, 1560–1609). Portrait of an African Woman Holding a Clock, c. 1583/85. Oil on canvas; 60 x 39.5 cm (23 ¾ x 15 ½ in). Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates: Louvre Abu Dhabi. Source: Tomasso Brothers.

About the Fashion

Her clothing is suitable for a middle-class woman’s best set of garments and accessories. This is notable because if she is a seamstress, then she has far more means than the usual working woman, akin to a lady’s attendant rather than a neighborhood laundress.

She is wearing a simple black sottana (or gamurra; a kirtle or bodiced petticoat) that sits almost off of the shoulder and which can be understood as a kind of day dress (Condra 24). Examples like this are rare to see in portraits because of their informality and its plainness; the wealthiest women wear more luxurious fabrics, and almost always choose to wear a veste or zimmara (overgown) on top for maximum effect (Fig. 7) (Frick 309). This is indisputably the way the cut-off sitter at right is dressed; her high, open collar and ruff are sure signs of a veste, even if we cannot see most of her outfit. Most women working day-to-day were wearing sottanas alone as their primary garment, and paintings of domestic and street life often show them being worn without the usual tied-on sleeves (Fig. 8).

The sottana in this painting is probably made of sensible, yet fashionable, black wool, but might be silk taffeta. It has three rows of velvet trim applied around the bodice in a typical design also seen in the extant sottana in figure 9. While silk was more luxurious, any fabric dyed in black sent the message that the wearer had means: Black was power. Black dyes were extremely expensive, meaning that only the elite could wear black fabric – “whether for mourning, as a symbol of authority or piety, or simply as a fashion statement” (Steele n.p.). Black dyes were so sought-after that they were subjected to legal restrictions as dyers suffering from the prices of dyestuffs had begun doctoring their recipes, which led to flawed results. In Fashion and Masculinity in Renaissance Florence (2016), Elizabeth Currie describes that black clothing also held allure for artists:

“The depiction of relatively plain, black garments allowed artists to concentrate more on the silhouettes and sculptural forms of dress, as well as contrasting types of textiles, rather than prioritizing surface decoration.” (n.p.)

Indeed, the black velvet trim on her bodice absorbs more light than the material it sits on, and the trim on the other woman’s sleeves reflects light as satin does.

Underneath her sottana, the sitter is wearing a linen camicia (shift; chemise) visible at her neckline and wrists. In The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing through World History (2008), Jill Condra writes about camicias:

“Since the early Renaissance, [the camicia] played a key role in the composition of the dress of the aristocracy. Immaculate linen shirts, sometimes embroidered or trimmed with lace, discreetly picked out from the neck lines in the cuffs of the sleeves, demonstrating the personal cleanliness of the higher social classes.… The beauty and fineness of these shirts are clearly visible in many paintings, as is the beautiful embroidery that trims the borders… Every piece of clothing, whether silk or linen, was embroidered or decorated to make it beautiful.” (26)

Some metallic edging is visible at the very top of her neckline; this may be metal-thread bobbin lace, a luxurious and subtle touch (Fig. 10). Camicias in this era had loose bodies and voluminous sleeves, parts of which are often visible through open seams in the sleeves of overgarments.

While pairs of bodies (the precursor to stays and corsets) were beginning to be worn in this period, it is unlikely that this sitter is wearing them (Hennessy 94). The bodices of dresses like this are stiffened internally with methods like pad-stitching and layers of linen covered in hide glue, and serve to keep her bust supported and the weight of her cotes (skirts) distributed (dal Poggetto 321). Another garment that she might be wearing is a pair of calze (drawers; under-pants), which were beginning to be worn by women in Spain and Italy in this period (Cunnington 44, 52).

While we cannot see the shape of her skirt, we can deduce that it resembles the example in figure 11 and is soft and bell-shaped. While ladies in Spain, France, and England were wearing the farthingale at this time, it was not widely worn by Italians (Cunnington 50-52, Hennessy 95).

The sitter’s other accessories are a fine but simple partlet (bavaro; neckerchief) and a caul (either magnosa or rezzolla in-period), which is the “trellis-work coif” worn over her hair (Cumming 43). The partlet is either linen or silk and is as transparent a fabric as she could purchase, but it is quite plain. Partlets were originally used as a touch of modesty and sun covering, but for the wealthy were yet another place to demonstrate their means (Cumming 150). The most luxurious partlets at this time were pearl-studded and embroidered with precious metal threads (Fig. 11).

Cauls were particularly popular in Italy; women of other countries tended to veil or cap off their hair with fabric rather than a net (Cumming 85, Laver 94-95) (Fig. 12). Everyday hairstyles were achieved at this time usually by weaving a tape (ribbon) through two braids and wrapping them around the head (visible in figure 11), or by braiding the hair into a bun and pinning it at back. Her hairstyle is plain, but styled correctly, and parted in the center as any woman’s would have been (Hennessy 95).

The sitter is also wearing several pieces of jewelry, including a coral necklace and gold and pearl earrings. Jill Condra explains how these particular pieces are quintessentially Italian:

“Among the favorite precious materials [for jewelry] were diamonds….Typically Italian is the use of coral, particularly in the south. Pearls have special meaning because of their naturally elegant appearance and their symbolic meaning of chastity.” (31)

While coral was less expensive than pearls, red coral jewelry in particular was a popular accessory in Italian paintings (Pointon 127). Coral was understood to have protective qualities, and pearls symbolized purity and the worldly exotic (Pointon 86, 111). While many men and women did wear earrings in this period, it should be noted that a common stereotype was to depict Black people wearing gold earrings. Gold – and pearls – were associated with Africa, and thus found a way even onto the ears of Black children in portraiture, whether or not those children were African or actually had earrings in reality (Fig. 13) (Walker 88).

And of course, she has two pins and a needle in her bodice, and she holds an ornate portable clock. Pins and needles looked much the same in the sixteenth century as they do today, though they were made by hand (Fig. 14). The golden clock, expensive and delicate, has been interpreted further in several ways: as a Christian symbol for the transcience of life (Walters 43), a signifier of modernity and scientific achievement, and a symbol of Temperance, a cardinal virtue (Tomasso). Interestingly, clocks “small enough to fit inside a lady’s purse” were a both a technological and fashion novelty during this time, bought by women like Isabelle d’Este to show off (Condra 30).

The aspect of her dress that most signals her position in the middle or working class is its simplicity, but the lack of falling ruff or standing collar on her partlet is also a sign. Luxurious sottanas could be worn for portraits at this time, but the dominant fashion was to wear a veste over it (Fig. 15), and generally to wear a glittering or embroidered linen partlet with standing collar no matter the gown (Fig. 16). That she does not wear one means that she is not part of the household on the same level as the now-missing sitter to her left, whose collar and veste are partly visible. She may be a seamstress or a domestic attendant, but she is unlikely to have been sister or daughter to that other sitter.

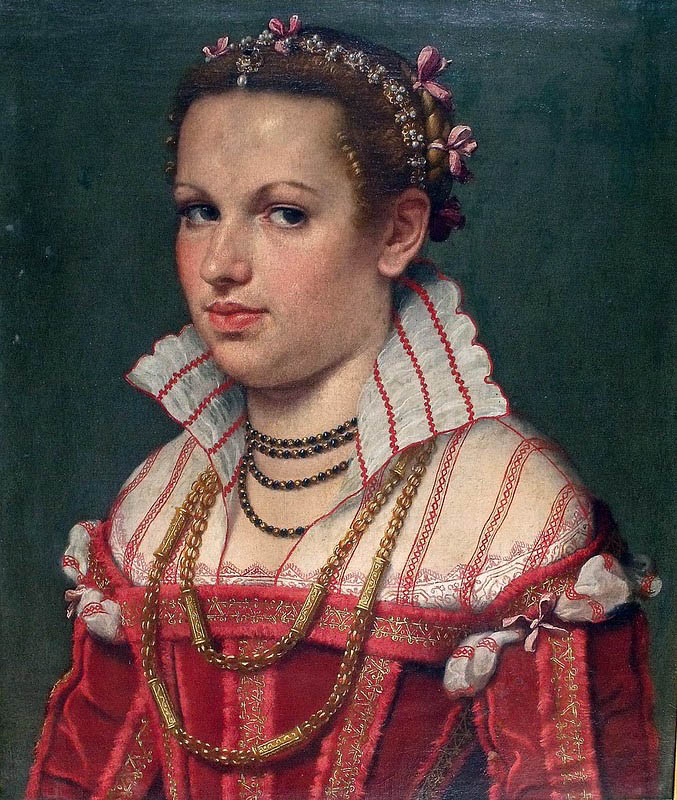

The portrait in figure 17 is an example of a sitter wearing a sottana without a standing collar on her partlet, but it is made out of a more luxurious damasked or brocaded silk satin and has dagged cutouts (triangular designs) on the shoulders. Importantly, it is also of the fashionable cut in the 1580s – the Black sitter’s sottana has the higher, straighter front of the red example in figure 15, which is from twenty years earlier. A fashionable sottana in the 1580s was more curved, with a lower neckline and the beginnings of what the English called a peascod belly, with a rounded point at the bottom. It is possible that the picture has been misdated too late and that the Black sitter is perfectly in fashion, but the cut of the other woman’s veste is appropriate to the mid-1580s. It is more likely that she is either wearing an older gown or considered the older styles to be more practical in comparison to the new, curvy fashions.

While her dress is neither made of the most expensive fabric nor overly embellished, she is dressed well and has carefully accessorized with what may be her best pieces. The bit of metallic lace that peeks up above her neckline is one of the more expensive touches, all the more so for how subtle it is, and her long coral necklace and dark pearl earring add a touch of finery.

Fig. 7 - Lavinia Fontana (Italian, 1552-1614). Portrait of a Lady of the Gonzaga or Sanvitale Family, ca. 1585. Oil on canvas; 115 x 87 cm (45 ¼ x 34 ¼ in). New York: Robert Simon Fine Art. Source: RSFA

Fig. 8 - Federico Zuccari (Italian, 1540/1-1609). Detail from Scenes from the Life of the Artist's Family, 1579. Fresco. Rome: Palazzo Zuccari. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 9 - Agostino d'Agobio (Italian). Woman's sottana (petticoat) with sleeves, ca. 1560. Crimson silk velvet with metallic thread. Pisa: Museo di Palazzo Reale. Source: Anéa

Fig. 10 - Designer unknown (Italian). Detail of metallic lace from neckline of blouse, Late 16th century. Silk, linen, metal thread. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 41.64. Gift of Sarah Sage, 1941. Source: MMA

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (Italian (Florentine)). Portrait of a Gentlewoman, 1550s. 37435. Source: University of Bologna

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (Italian (Venetian)). Portrait of a lady, Late 16th century. Oil on canvas; 39.4 x 31.1 cm (15½ x 12¼ in). New York: Christie's, Lot 115, Sale 251, 26 January 2011. Source: Christie's

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown (Italian (Venetian)). Detail of Portrait of a courtesan and her servant, second half 16th century. Oil on panel; 47 x 43 cm. Chemilli: Edery Jean-David. Source: Antic Swiss

Fig. 14 - Maker unknown (British). Length: 1.3 cm, 1620-35. Silvered brass; length: 1.3 cm. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 123D-1900. Given by R. J. Andrews. Source: VAM

Fig. 15 - Scipione Pulzone (Italian, before 1550-1598). Portrait of a Lady, ca. 1585. Oil on canvas; 119 x 91.2 cm (46 7/8 x 35 7/8 in). Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 37.605. Source: WAM

Fig. 16 - Giovanni Battista Moroni (Italian, c.1522-1579). Portrait d'Isotta Brembati Grumelli, 1550-1555. Oil on canvas; 55 x 47 cm. Bergame: Accademia Carrara. Source: Flickr

Fig. 17 - Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti) (attr.) (Italian (Venetian), 1518-1594). Portrait of a Young Lady, 1580s-90s. Oil on canvas; 114 x 100 cm. Madrid: Museo del Prado, P00484. Source: Fine Art America

This sitter was not simply in the painting to be a prop or accessory: she is dressed sensibly in European fashion without any gaudiness (Kaufmann 2017, 102). Unlike the Black boy in figure 13, who may have been a real person but was certainly only painted as a statement of wealth and exoticism, the Black sitter in this painting must have been a valued member of the household, and had a close enough relationship to the other sitter to be included in the painting.

Its Legacy

This portrait, until recently kept in private collections, received massive waves of publicity when it was featured in The Walters Art Gallery’s 2012 exhibit Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. There has been a push in the 21st century to reveal and center Black and indigenous people in the Western art canon, and this portrait is an important part of that movement.

One artist, Shasta Schatz, was inspired to reproduce the portrait in 2020 (Fig. 18). She chose black silk taffeta for the fabric of her dress instead of wool, and full shots of the gown show what the rest of the skirt probably looked like for the original sitter (Fig. 19).

Fig. 18 - Shasta Schatz (American). 16th Century Portrait, June 2020. Silk, linen, velvet. Source: Green Linen Shirt

Fig. 19 - Shasta Schatz (American). 16th Century Portrait, June 2020. Silk, linen, velvet. Source: Green Linen Shirt

References:

- Barton, Lin, C. van Tuyll van Serooskerken, Nicholas Turner, and Daniele Benati. “Carracci family.” Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 18 Jun. 2020. Grove Art Online

- Condra, Jill. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Clothing Through World History. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2008. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/603461740

- Crawford, Francis Marion. Gleanings from Venetian History. Vol. 2. London: Macmillan, 1905. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888835718

- Cumming, Valerie, Phillis Cunnington, and C. Willett Cunnington. The Dictionary of Fashion History. Oxford: Berg, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/751449764

- Cunnington, C. Willett, and Phillis Cunnington. The History of Underclothes. Dover Publications, 2013. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868279842

- Currie, Elizabeth. Fashion and Masculinity in Renaissance Florence. New York: London, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990370830

- Frick, Carole Collier. Dressing Renaissance Florence: Families, Fortunes, and Fine Clothing. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62133195

- Hennessy, Kathryn, and Anna Fischel. Fashion: The Definitive History of Costume and Style. New York: DK Publishing, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/915140562

- Honeyman, Katrina, and Jordan Goodman. “Women’s Work, Gender Conflict, and Labour Markets in Europe, 1500-1900.” The Economic History Review, New Series, 44, no. 4 (1991): 608-28. Accessed June 19, 2020. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2598/stable/2597804

- Kaufmann, Miranda. “The Black Face of Renaissance Europe.” History Today, 21st May 2013. Accessed 18 June 2020. www.mirandakaufmann.com/historytoday21513.html

- Kaufmann, Miranda. Black Tudors: The Untold Story. London, England : Oneworld Publications, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1083265546

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/440744982

- Pointon, Marcia Rachel. Brilliant Effects: A Cultural History of Gem Stones and Jewellery. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/995573203

- Spicer, Joaneath, Kate Lowe, and Natalie Zemon Davis. Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. Baltimore: The Walters Art Museum, 2012. Worldcat | Available in full online!

- Schleier, Erich, and the Tomasso Brothers. “Portrait of an African Woman holding a clock, c. 1583/85.” Tomasso Brothers Fine Art, 27 January 2017. Accessed 18 June 2020. https://www.tomassobrothers.co.uk/artworkdetail/781241/18036/portrait-of-an-african-woman-holding

- Steele, Valerie. The Black Dress. New York: Collins Design, 2007. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/180148413