About the Portrait

Villers was the younger sister of Marie-Victoire Lemoine and a student of Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson, both accomplished artists in their own right who worked at the end of the eighteenth century. Villers completed this painting in the neoclassical style in her mid-twenties and has left us with several mysteries: who are the two figures seen though the window on the balcony, and who is the young woman in the painting? When it was previously attributed to David, the sitter was thought to be Charlotte du Val d’Ognes. Now that we know it was done by Villers, it is possible that we are looking at a self-portrait of the artist herself (Tinterow 3). However, it is still believed the sitter is Val d’Ognes, as she and Villers studied art together at this time (Higonnet).

Scholars posit that the scene through the window is of Val d’Ognes’ home along the Seine and that the room itself is a professional studio inside of the Louvre. It may even be that of Jean-Baptiste Regnault, whose wife Sophie Meyer managed a studio for female artists, making this painting a unique view into a female-dominated artistic space in the era (Higonnet).

Only one signed work that we know of exists by Villers (Fig. 2), though several other paintings are also attributed to her (Fig. 3), and despite similar subjects all three look somewhat different. It is apparent that she is an artist who is hard to pin down in history, and we must wait for more research to uncover her fully. Records show that first exhibited work at the Salon in 1799 and that she worked up to at least 1814 when she painted the Duchess of Angoulême, so there are likely other portraits by her in private collections that we are not yet aware of (Sotheby’s).

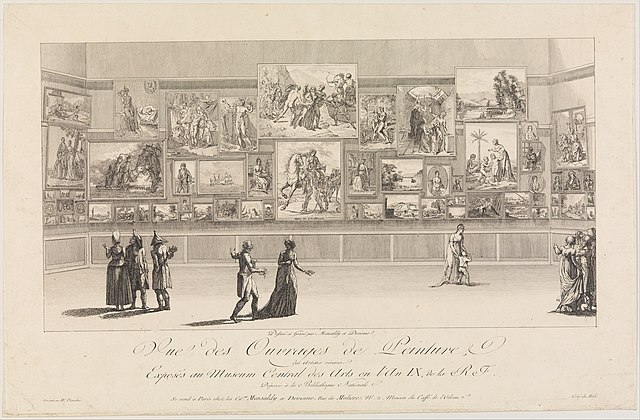

Fig. 1 - Antoine Maxime Monsaldy and G. Devisme (French). Vue des Ouvrages de Peinture, 1801. Etching; sheet: 24.8 x 38 cm (9 3/4 x 14 15/16 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 59.601.3(a). The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959. Source: MMA

Fig. 2 - Marie Denise Villers (French, 1774-1821). Une étude de femme d'après nature, 1802. Oil on canvas. Paris: Louvre, RF 173. Source: RMN Grand Palais

Fig. 3 - Marie Denise Villers (French, 1774-1821). A Young Woman Seated by a Window, ca. 1801. Oil on canvas. Private collection. Source: Sotheby's

Marie Denise Villers (French, 1774-1821). Young Woman Drawing, 1801. Oil on canvas; 161.3 x 128.6cm. (63 1/2 x 50 1/8in). Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, Mr. and Mrs. Isaac D. Fletcher Collection. 17.120.204. MMA

About the Fashion

The young woman in this painting is wearing the quintessential costume of the time: a classical-inspired chemise gown. The neckline of the dress is difficult to see because it is blocked by the young woman’s arm, but we can catch a glimpse of it appearing just underneath her bicep, showing that it has a low, rounded scoop neck. Tucked into the bodice is her kerchief, which is secured with a delicate gold-colored oval brooch and gives a more conservative neckline. At her raised waistline just beneath her bust is a pink silk ribbon tied in a bow at back. The skirt of the dress has a short train that is folded and gathered at the sitter’s feet. Trains were popular amongst fashionable elite women until about 1806 and can be seen in figure 4.

Her dress is most likely made from fine Indian muslin (cotton) as such materials were popular for this style (Johnston 40). An extant muslin gown from about 1800 can be seen in figure 5, showing the soft drape and diaphanous appearance such dresses have in real life. Her dress is a product of the neoclassical movement, and its simplicity and revealing elements are in defiance of Jacobin Puritanism and conventional morality (Ribeiro 121). In the June 1802 issue of The Ladies Monthly Museum, this style of dress was described as:

“Female demi-nudity… the close, all white, shroud-looking, ghostly chemise underdress of the ladies, who seem to glide like spectres with their shrouds wrapt tight around their forms… do justify the poet’s expression on the following line ‘Now sheer undressing is the general rage.” (Bradfield 86)

Underwear during this time had been reduced to a minimum of a linen chemise and a pair of stays for bust support, though the most daring young women might leave those at home (Bradfield 88). However, since this young woman’s dress is opaque, she was most likely wearing a plain white underdress just beneath her gown for modesty (Johnston 41).

Her hair is in a loose bun secured with a hair stick, similar to the hairstyle featured in figure 3. Her shoes are simple, flat, and cut low over the foot, as was the common style at home (Boucher 346). The long cashmere shawl draped over the chair would have been worn as a stole, linking the ensemble further to classical fashion and statues of dancers with shawls (Riberio 123). Accessories like these were often made of expensive cashmere and became popular after the Egyptian campaign (Boucher 347). These shawls were a necessity during this time because chemise gowns of cotton were thin and did not provide much warmth.

This costume was certainly hand sewn because the sewing machine was not invented yet. The young woman’s accessories may have been custom-ordered, but could also have been picked out in a shop.

This depiction sets down the image of an artist at work. Since her costume is relatively simple–we can’t even see any embroidery or a woven pattern like the one in figure 6–and the sitter isn’t wearing any visible jewelry, this is probably an outfit that she wore on a daily basis. Dresses like these were not designed for a special occasion, but could be dressed up with the right accessories and gold trim, as seen in figure 7. Considering that the sitter is wearing a chemise gown, we know both that she was fashionable and her family was wealthy enough to afford the muslin and cashmere that she is pictured with. As this was painted in 1801, it is right in step with the neoclassical style of the time.

Fig. 4 - François Gérard (French, 1770-1837). Madame Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Périgord, 1804. Oil on canvas; 225.7 x 164.8 cm (88 7/8 x 64 7/8 in). New York: Metropolitan Musuem of Art, 2002.31. Wrightsman Fund. Source: MMA

Fig. 5 - Designer unknown (English). Gown, ca. 1800. Muslin; underbust circ 80.5 cm. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.785&A-1913. Messrs Harrods Ltd.. Source: VAM

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (American). Woman's dress, ca. 1800. Cotton plain weave and leno weave (gauze), embroidered. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 42.680. Zoe Oliver Sherman Collection. Source: MFA

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (French). Costume Parisienne: Manches Lacées. Chainê en Or et Email., 1800-1801. Paper, etching; 18.3 x 11.2 cm. Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, RP-P-2015-26-152. S. Emmering Bequest. Source: Rijksmuseum

Its Legacy

T

his painting is so memorable in part thanks to the mystery that shrouds it. Even though we think we have identified the artist and sitter, at the Met the question of the cracked window-pane and the unidentifiable figures has persistently intrigued visitors and art historians alike (Tinterow 3). This sense of mystery and its relatable composition and content have influenced later artists not only to create modern riffs on the piece (Figs. 8-9) but also to produce a contemporary portrait that bridges past and present (Fig. 10).

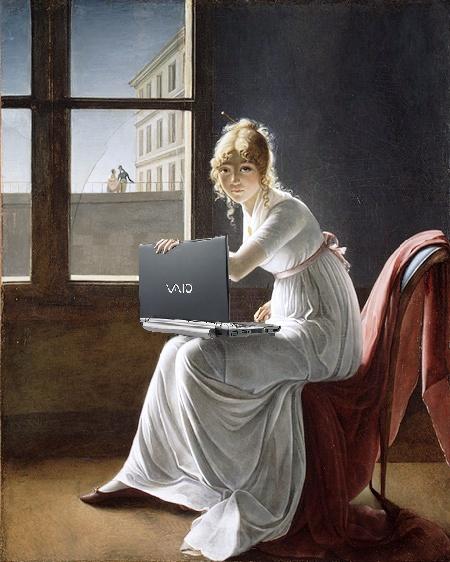

Fig. 8 - Munguia (Costa Rica, active 2009-). Web designer, September 15, 2015. Digital. Source: ToonPool

Fig. 9 - Mike Licht (American, active 2007-). Young Woman Blogging, after Marie Denise Villers, August 6, 2008. Photoshop. Source: Flickr

Fig. 10 - Stephanie Guse (German, active Austria, 1971-present). Wanna Have: Villers (after Marie-Denise Villers "Young Woman drawing”, 1801), 2019. Photography, glass, paper, aluminum; (50.4 w x 63.4 h x 0.8 d in). Source: Saatchi Art

The style of dress, with its high waist and columnar silhouette, returned in the 1960s and again in the 2020s (notably with the release of the television show Bridgerton). While it is common to see the high ’empire’ waist featured in this design incorporated into fashions of the current day, we have never truly witnessed a return of the chemise gown. Perhaps they are too impractical, being so thin and difficult to keep clean. Plain cotton is no longer an expensive fabric around the world, so today when we see these long white gowns, they are often silk satin or chiffon wedding dresses (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 - Stephanie White for Odylyne the Ceremony (American). Emilia dress, Her Week of Wonders collection, 2022. Silk organza. Los Angeles. Source: Odylyne the Ceremony

References:

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The History of Costume and Personal Adornment. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1967. Worldcat.

- Bradfield, Nancy. Costume in Detail: Women’s Dress 1730-1930. Costume & Fashion Press, 1968. Worldcat.

- Higonnet, Anne. “Through a Louvre Window.” Journal18, Iss. 2 (Fall 2016). https://www.journal18.org/issue2/through-a-louvre-window/

- Johnston, Lucy, and Marion Kite. 19th-century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2005. Worldcat.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Young Woman Drawing (Charlotte du Val d’Ognes).” Accessed November 4, 2015. http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/437903

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Fashion in the French Revolution. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1988. Worldcat.

- Sterling, Charles. “A Fine ‘David’ Reattributed.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 9, no. 5 (1951): 121–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3257483.

- Sotheby’s. “Marie-Denise Villers, lot 66, Old Master Paintings.” Sotheby’s. https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2009/old-master-paintings-european-sculpture-antiquities-n08560/lot.66.html

- Tinterow, Gary, and Kathryn Calley Galitz, Masterpieces of European Painting, 1800-1920, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2007. Read free on Google Books.