The young man in this portrait, dressed in formal French aristocratic style, represents the final flourish (or last gasp?) of the ancien régime in the last years before the French Revolution.

About the Portrait

Marie-Victoire Lemoine (1754 – 1820) painted this Portrait of a Youth in an Embroidered Vest in 1785, during an era of conspicuous excess from the aristocracy and of building revolutionary fervor among the working classes. Raised in an artistic but middle-class family in Paris, Lemoine (Fig. 1) used connections to the French court to paint such aristocratic sitters as the Princesse de Lamballe and the Mademoiselle de Chartres (NMWA). She never married, instead preferring to focus on her artistic career (Kuntsevich).

She studied under Guillaume Ménageot (1744-1816), a religious painter in the Grand Style who had studied in turn under François Boucher (1703-1770) (Kuntsevich). While she was already accomplished by 1785, she was not able to submit work to the famed Paris Salon until after the Revolution in 1796, as postwar reforms expanded access to a greater number of women artists (Met). Her first works in public view were genre paintings (Fig. 2) and miniatures, and she continued to exhibit at the Salon until 1814 (NMWA). Her work is often compared to that of her contemporary, noted artist Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun (1755-1842).

About the Sitter

The sitter was previously identified as Zamor (christened Louis-Benoît), a boy enslaved by Madame Du Barry, mistress to King Louis XV. This has since been disproved; Zamor was Bengali, not African or of African descent (Bhaduri n.p.). The Cummer museum now posits that the sitter may be either “Scipio or Narcisse, both linked to the house of the Duchess d’Orléans,” as she commissioned Lemoine for work, but it remains a mystery (Damiano).

By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, there were four to five thousand Black people living on French soil, and untold more in France’s colonies (Chatman 144). While none that we know of were landed nobility, some were in positions of wealth and influence, especially in the French Caribbean (Martone 219). While France had prided itself since the sixteenth century on the “Freedom Principle,” in which any enslaved person would be freed upon touching (continental) French ground, this ‘sanctity’ was eroded in the next two hundred years (Chatman 145). Some Africans were certainly being enslaved in the country despite the Principle. Some enslaved women bore children by white French aristocrats: two of the most famous of these biracial children, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas and Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (Fig. 3), went on to fight in the French Revolution in the 1790s (Martone 219). The Chevalier even led a regiment of Black soldiers, the Légion Saint-Georges, during the Revolution, though whether all were free by law is unknown.

Free Black life was heavily policed in this part of the century, with forced registration, identification cards, and bans on interracial marriage (Martone 220). This sitter, despite the appearance of fine clothing, is likely a servant, his function in the house primarily decorative. Black people were seen as objects by the elite regardless of their legal status, a mindset aided by France’s position as a major player in the trade of enslaved people from Africa. Aristocrats and bourgeoisie alike engaged in the practice of hiring unusual servants as status symbols: beautiful boys, muscular men, foreigners (like the Swiss), and Black people (Maza 206). Employers – or enslavers – were very careful to maintain the appearances of servants whom the public saw most frequently, including pages, coachmen, and doormen (Maza 203). They were dressed in fine clothing in order to be shown off as evidence of the homeowner’s wealth and social status, a practice that continued until the Revolution (Maza 205, 209). This objectification is less serious in the context of the white servants; for those who were Black, it fed into a historical paradigm of degradation (Fig. 4) and devalued the little personhood they were allowed in late 18th-century France.

This young man is probably a page or doorman for a wealthy household. His portrait is notable in that he was painted alone, rather than subordinate to a white sitter (Fig. 5). His clothing is fine, and alone either marks him as the son of a wealthy family or as a public-facing servant working for one. If he is a servant, then his clothing was likely selected for him, rather than being his choice. Lemoine, at least, has done him artistic justice by painting a background which flatters and highlights his appearance; many paintings featuring Black sitters meld their features into the darkness instead. In his hair, too, small curls are carefully rendered.

Fig. 1 - Marie-Victoire Lemoine (French, 1754-1820). Portrait of the artist, three-quarter-length, holding a palette and brushes, ca. 1790. Oil on canvas; 67.6 x 49.5 cm (26 5/8 x 19 ¼ in). New York: Christie's, Sale 16185, 1 November 2018, Lot 1177. Source: Christie's

Fig. 2 - Marie-Victoire Lemoine (French, 1754-1820). The Interior of an Atelier of a Woman Painter, 1789. Oil on canvas; 116.5 x 88.9 cm (45 7/8 x 35 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 57.103. Source: MMA

Fig. 3 - After Mather Brown (1761–1831) William Ward (British, 1766-1826). Portrait of Joseph Bologne de Saint-George (1745-1799), 1788. Engraving. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de france, FRBNF14793223. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (French). "A Moorish page is the ideal accessory for a lady who wishes to show off a pale complexion", ca. 1689. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de france. Sarah C. Maza, Servants and Masters in 18th-Century France, p. 206. Source: JSTOR

Fig. 5 - John Hesselius (American, 1728-1778). Charles Calvert and His Slave, 1761. Oil on canvas; 127.7 x 101.3 cm (50 1/4 x 39 7/8 in). Baltimore Museum of Art, 1941.4. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Marie-Victoire Lemoine (French, 1754–1820). Portrait of a Youth in an Embroidered Vest, 1785. Oil on canvas; 65.1 x 54.6cm (25 ⅝ x 21 ½ in). Jacksonville, FL: Cummer Museum, AP.1994.3.1. Purchased with funds from the Cummer Council. Source: Cummer Museum

About the Fashion

In the Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition catalog Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715-2015 (2016), curators Sharon Sadako Takeda, Kaye Spilker, and Clarissa Esguerra describe the ‘business formal’ dress code of the eighteenth century:

“French aristocrats and wealthy merchants of the mid-eighteenth century commonly donned a matching three-piece suit, typically made of fashionable silk cloth in alluring pastel colors, to conduct business affairs. The suit consisted of a collarless coat, cut long with a full pleated skirt, and worn with a hip-length waistcoat and knee-length breeches.” (140)

Accordingly, this sitter wears a white silk satin justaucorps or coat over an embroidered satin waistcoat, a white linen shirt, and a white linen stock. While we cannot see his lower half, his breeches are probably made of matching white satin, and he must be wearing stockings – possibly silk – and leather buckled shoes as well. A similar extant satin ensemble can be seen in figure 6, showing how the buttons continued onto the sleeve cuffs. The sitter’s swathes of silk satin, along with his waistcoat embroidery, stand out as rather French (Fig. 7) as the British were by this time usually wearing simpler, less ornate clothing, often out of wool (Fig. 8).

Silk was a quintessentially French commodity, and had been since the sixteenth century; it “became synonymous with continental luxury,” while the British and Americans instead preferred native woolens (McNeil 238). The more comfortable, less luxurious fashions of the English, including the new frock coat, began to pervade everyday wear and portraiture in the 1770s and 1780s while the court at Versailles continued to mandate silk velvets and satins (Fig. 9) (McNeil 239). The clothing that this sitter wears is a symbol of aristocracy and luxury, and in a few short years could alone be a death sentence. Once the Revolution began in 1789, silks and satins – any symbol of the ancien régime and courtly wealth – lost all popularity in favor of common woolens and linens (McNeil 241).

In her book Costume in Pictures (1964), historian Phillis Cunnington describes men’s coats in the latter half of the eighteenth century:

“The side seams of the coat were increasingly curved back, bringing the hip buttons closer together and narrowing the back. At the same time the front skirts were cut back, eliminating, in the 1760s, the flared skirts, which, by the 1790s, were reduced to squared coat-tails. This coat, with modifications, has survived for men’s evening dress to this day. A narrow stand collar was added from 1769, which increased in height in the 1780s and 1790s. Sleeves were close-fitting with rather smaller round cuffs or made with a short button vent.” (99-100)

Compare the ivory suit the sitter wears with the livery worn by the young cupbearer in figure 10, who probably lives in the British Colonies. The latter wears a newer style with a turned collar in a more sensible dark color suitable for a day’s work. Wealthy Frenchmen continued to wear – and dress their servants in – silks and embroidery beyond the time in which they were fashionable in other countries. While our sitter’s clothing is stylish enough in cut with a standing collar and plain buttons, these are not the clothes of a self-made European (as the man in figure 8 might be) and neither are they at the cutting edge of French fashion. The bourgeoisie wore higher collars, often folded over, sharply curved upper fronts, and had a predilection for stripes (Fig. 11). This white satin suit is in the fashion of the nobility (Fig. 9), and no longer in vogue elsewhere.

Another interesting aspect of his coat is its fit: despite the rumple behind his neck, it would have been considered well-fit in the period. This is a feature in portraiture of even the very rich, where a fold runs up from under the arm over the chest and around the back of the neck (Fig. 12). It is more often seen in silk coats, which are more difficult to fit to a body than coats of wool, which can be steamed and eased around curves (Hollander 261). The coat may also have been made with some room for him to grow into as his shoulders broadened.

In Reigning Men, authors Takeda, Spilker, and Esguerra go on to discuss how the waistcoat (vest or gilet) was “a critical element of the man’s ensemble” during this time (214):

“A man’s ensemble in the late eighteenth century was elevated by the superior quality of its waistcoat, many of which were embroidered with exquisite garlands of blossoms… Novelty in patterns and techniques was requisite and fashions changed rapidly, so a stylish man might have needed a large number of waistcoats to complete his wardrobe.” (213)

“In the late 18th…[century] the splendid man’s attire was frequently festooned with flowers. Designs on textiles and dress mirrored the elaborate architecture and floriculture of the landed gentry’s majestic gardens; designers, both of textiles and landscape, increase their mastery by studying with flower painters.” (212)

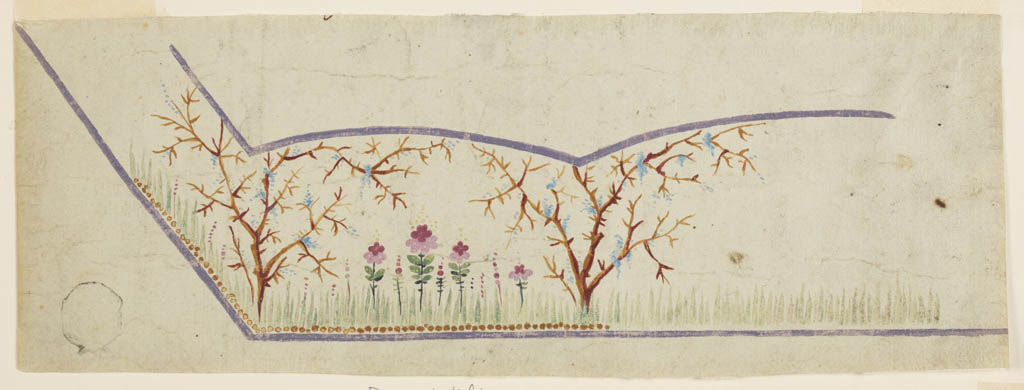

An extant embroidered vest similar to the sitter’s is visible in figure 13, and in figure 14 there is a painted design for embroidery underneath a waistcoat pocket. While we cannot see this area on the sitter’s clothing, if his waistcoat is up to date then it should be at least this short, with the pockets close to the hem. The pockets were likely false, as on women’s clothing today, for a sleeker look. The back of his waistcoat, rarely seen, was probably made of a cheaper fabric like linen (Laver 135).

Cunnington goes on to describe the evolution of the waistcoat in this era, which paralleled that of the coat:

“The waistcoat, now sleeveless, became increasingly short, and by the 1780s was usually square cut without a slope away from the last button. A small stand collar was added in the 1760s, which was heightened in the 1780s to correspond with the code. Double-breasted waistcoats were not popular until the 1780s, after which they were usual.” (103)

While the sitter’s coat buttons are probably simple wooden discs covered in matching satin, his small waistcoat buttons are delicately embroidered to match the rest of the garment. This was a luxurious touch that is nevertheless common on such pieces (Fig. 15).

Barely visible is his shirt, the linen layer protecting all of his silks from dirt and body oils (Fig. 16). Its collar protrudes along his jaw, and the lace jabot along the edge of the waistcoat opening is sewn to his shirt’s opening (Doering 201). Cunnington points out that waistcoats were “often left open to display the frilled shirt front. The shirt ruffles (frills) at the wrist were always evident” (78). See figure 16; the white cuffs emerging over the man’s hands from under the coat sleeves are part of his shirt, as are the ruffles by his neck. Lace was yet another marker of wealth and refinement in the 18th century, as it was still all made by hand using either bobbins or a needle and was extremely time-consuming.

He also wears a white stock, likely of linen; while cotton was sometimes used, linen was still much cheaper to purchase (Doering 201). Cunnington describes this kind of neckwear:

“For neck-wear the cravat was going out of fashion, though revived by the Macaronis in the 1770s. The stock was now the vogue and, like the coat collar, increased in height and was sometimes stiffened with pasteboard…From c 1785 a stock formed of muslin, wound several times around the neck and nodded in front, was again called a cravat.” (104)

Stocks were the eighteenth-century equivalent of clip-on bowties; they came pre-gathered and secured in the back, often with a buckle, so that all the labor of winding a cravat or neckcloth around one’s neck and carefully arranging it was no longer necessary. An extant example is visible in figure 18. Like all linens, part of their function was to protect the expensive outer clothing from sweat and body oils.

The sitter’s hair is not styled, but cut so that it approximates a 1780s-appropriate shape. Men during this time wore their hair – or wigs – with fullness at the top and sides, with a tail or queue at back (Figs. 7, 17). The hair at the sides usually achieved fullness by being rolled into what were called ‘buckles’, and both hair and wigs were pomaded and powdered to stay sculpted and clean (Lewandowski 41, Whitacre 141).

In his essay “Despots of Elegance: Men’s Fashion, 1715-1915” (2016), Peter McNeil describes an obsession with wigs:

“In the eighteenth century, men of all classes wore wigs; their cost dropped over the course of the century and all manner of novelties such as springs to secure them were invented. Wigs were dressed, pomaded, and dusted with powder, including colors such as green or lilac for fashionable, urbane men.” (237-8)

The highest and most elaborate hairstyles were the province of the wealthy French (Fig. 17), as with dress; people in other countries or in other occupations were not bound to the same extremes. The British man in figure 8 has the side buckles and queue, but no fullness on top of his head; the smiling young Colonial man in figure 10 has a close shave with no fashionable hairstyle at all. Our sitter is somewhere in between – his hair is not styled, but it is long enough to be full, and cut so that there is an emphasis on its height and width.

While cosmetics might not be the first thing a viewer thinks of when looking at this picture, they are an important aspect of dress to consider. In her entry “Makeup and Beauty, 1715-1785” (2016), Katy Werlin describes the culture of cosmetics in the eighteenth century:

“Makeup was worn by both men and women and was an important status symbol and declaration of aristocratic identity. As such, it was not meant to convey a natural appearance but rather a deliberately artificial one. The heaviness of cosmetic application varied. Makeup was heavier and more pronounced in France than England and its American colonies. Makeup helped to create an ideal complexion, with pure, smooth white skin; pink cheeks; and red lips.” (166)

The sitter is not wearing any face powder; for him, a white man’s ideal of beauty is simply not possible. But there is no reason to think that he is not wearing a touch of rouge on his lips and cheeks, in keeping with the concept of a fashionably healthy flush.

The Youth in an Embroidered Waistcoat is dressed as a member of the ancien régime; willingly or not, he is part of an empire that was taken down by revolution four years later. His fine clothing fits well enough, and his hair is cut at the correct length to produce a shape somewhat fashionable for the 1780s. It is possible that he or his family made their own fortune and that he sits before us a free man beholden to none. However, it is more likely that he had no agency in the selection of the clothing that he wears, and despite the loveliness of the portrait, that he was painted to be an object of display – another piece of luxury on the walls of a rotting regime.

With thanks to Paul Malcolm White.

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (British). Breeches and vest, ca. 1780-1785. Gold silk satin. Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove. Source: Flickr

Fig. 7 - Adolf Ulric Wertmüller (Swedish, 1751–1811). Jean-Jacques Caffieri, 1784. Oil on canvas; 128.9 x 95.9 cm (50 3/4 x 37 3/4 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 63.1082. Ernest Wadsworth Longfellow Fund. Source: MFA

Fig. 8 - Allan Ramsay (attributed) (British, 1713–1784). Portrait of an African, ca. 1780 (attr. ca. 1757-60). Oil on canvas; h 61.8 x w 51.5 cm. Exeter: Royal Albert Memorial Museum, 14/1943. Gift from Percy Moore Turner, 1943. Source: ArtUK

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (French). Three-piece Men's Suit, 1785-1790. Silk velvet, silk satin, silver metal thread, spangles, wood, embroidery; coat length 104 cm. Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, DE-MUS-018417. Source: Google Arts & Culture

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (Colonial School). A Servant, ca. 1770. Oil on canvas; 76.2 x 63.5 cm (30 x 25 in). London: Philip Mould. Source: Historical Portraits Image Library

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (French). Frac (Frock coat), 1785. Taffetas de soie chiné à la branche; h. 135, l. 43 cm. Galliera musée de la Mode de la Ville de Paris, GAL1960.58.12. Source: Joconde

Fig. 12 - Jean-Baptiste Greuze (French, 1725–1805). Charles Claude de Flahaut (1730–1809), Comte d'Angiviller, 1763. Oil on canvas; 64.1 x 54 cm (25 1/4 x 21 1/4 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 66.28.1. Source: MMA

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (French). Man's waistcoat, ca. 1785. Ivory silk taffeta with silk embroidery in satin stitch; cbl: 45.7 cm, w: 83.8. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1943-17-6. Source: PMA

Fig. 14 - Mademoiselle Favel (French). Design for embroidered waistcoat, ca. 1785. Brush and gouache on laid paper; 10.3 x 28.1 cm (4 1/16 x 11 1/16 in). New York: Cooper Hewitt Design Museum, 1920-36-36. Source: Cooper Hewitt

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (British). Suit detail, ca. 1770. Silk, cotton. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.66.37.1a–c. Source: MMA

Fig. 16 - Designer unknown. Men's shirts, late 18th-early 19th century. Linen. Brussels: Fashion & Lace Museum. Source: BXLM

Fig. 17 - Antoine Vestier (French, 1740-1824). A Cellist, 1788. Oil on canvas. Arizona: Phoenix Art Museum, 1963.28. Source: PAM

Fig. 18 - Designer unknown (American). Man's stock, Last quarter of the 18th century. Plain weave linen; 10.5 x 45.7 cm (4 1/8 x 18 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 99.664.6. Gift of Miss Ellen A. Stone, 1899. Source: MFA

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Its Legacy

During the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic, singer, writer, and presenter Peter Braithwaite spent time re-imagining a number of historical portraits featuring Black sitters. This sitter was lucky enough to be one of them, and was given an embroidered shirt and a space-age coat with high-key lighting (Fig. 19).

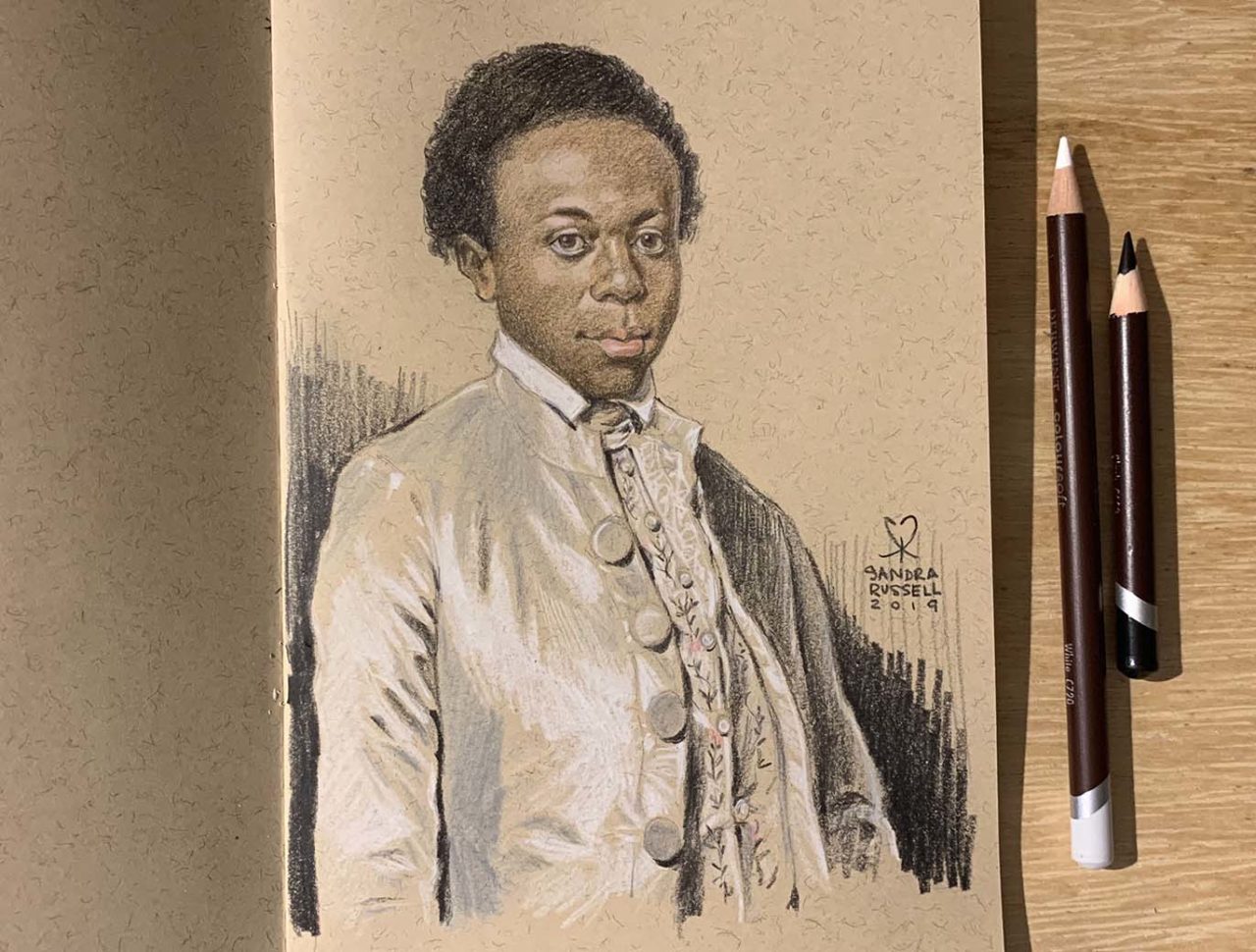

In 2019, an art challenge went out on Twitter and Instagram to redraw what was then still called the ‘Portrait of Zamor,’ and several artists tried their hand at doing our nameless sitter justice in a variety of media (Figs. 20 & 21). Artist Paul Murphy reclaimed the youth’s Frenchness by simply drawing in the remains of the national flag rather than the gaudy silk satin outfit in which he was originally dressed (Fig. 22).

Fig. 19 - Peter Braithwaite (British). Marie-Victoire Lemoine: Portrait of a Youth in a Embroidered Vest (1785), April 2020. Source: Twitter

Fig. 20 - Andrew Fraser (Scottish). #portraitchallenge, August 2019. Procreate. Source: Instagram

Fig. 21 - Sarah Russel (British). Pencil sketch version of Louis-Benoit Zamor, painted by Marie-Victoire Lemoine in 1785, August 2019. Pencil and paper. Source: Twitter

Fig. 22 - Paul Murphy. Portrait of Zamor, August 2019. Digital art. Source: Twitter

References:

- Bhaduri, Saugata. Polycoloniality: European Transactions with Bengal from the 13th to the 19th Century. London: Bloomsbury Publishing India Pvt. Ltd, 2020. Worldcat / Google Books

- Chatman, Samuel L. “‘There Are No Slaves in France’: A Re-Examination of Slave Laws in Eighteenth Century France.” The Journal of Negro History 85, no. 3 (2000): 144-53. Accessed July 2, 2020. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2598/stable/2649071

- Cunnington, Phillis. Costume in Pictures. New York: Studio Vista/Dutton, 1964. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1031249891

- Damiano, Nelda. “On Tour…” Cummer Museum Blog, 30 Jan 20??. Accessed 1 July 2020. https://blog.cummermuseum.org/on-tour/

- Doering, Mary D. “Neckwear, Men’s, 1715-1785.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Hollander, Anne. “Heroes in Wool.” In McNeil, Peter, and Vicki Karaminas. The Men’s Fashion Reader. Oxford: Berg, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/271812061

- “The Interior of an Atelier of a Woman Painter.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 1 July 2020. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436875

- Kuntsevich, Sasha. “#5WomenArtists: Marie-Victoire Lemonie – Portrait of a Youth in an Embroidered Vest.” Cummer Museum Blog, 26 March 20??, Accessed 1 July 2020. https://blog.cummermuseum.org/5womenartists-marie-victoire-lemoine-portrait-of-a-youth-in-an-embroidered-vest-2/

- Laver, James. Costume and Fashion: A Concise History. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/440744982

- Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., and Dan Lewandowski. The Complete Costume Dictionary. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1130805377

- Martone, Eric. Encyclopedia of Blacks in European History and Culture. Vol. 1. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 2009. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/552037385

- Maza, Sarah C. “The Uses of Loyalty.” In Servants and Masters in 18th-Century France: The Uses of Loyalty, 199-244. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1983. Accessed July 2, 2020. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2598/stable/j.ctt7ztrbk.12

- McNeil, Peter. “Despots of Elegance: Men’s Fashion, 1715-1915.” In Takeda, Sharon Sadako, Kaye Durland Spilker, and Clarissa M. Esguerra. Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715-2015, 235-248. Munich: Prestel, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/983760658

- NMWA. “Royalists to Romantics: Spotlight on Marie Victoire Lemoine.” The National Museum of Women in the Arts, 8 June 2012. https://nmwa.org/blog/royalists-to-romantics-spotlight-on-marie-victoire-lemoine/

- Takeda, Sharon Sadako, Kaye Durland Spilker, and Clarissa M. Esguerra. Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715-2015. [Los Angeles County Museum of Art, April 10-August 21, 2016]. Munich: Prestel, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/983760658

- Werlin, Katy. “Makeup and Beauty, 1715-1785.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699

- Whitacre, Janea. “Head Wear, Men’s and Women’s, 1715 to 1785.” In Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe. José Blanco, Mary D. Doering, Patricia Hunt-Hurst, and Heather Vaughan Lee, eds. Santa Barbara, California : ABC-CLIO, 2016. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/904505699