About the Look

T his gown was worn by Queen Victoria of England at her wedding to Prince Albert in the year 1840. It garnered a great deal of press attention at the time, as the royal wedding was highly publicized.

The structured, eight-piece bodice features a wide, open neckline. The off-the-shoulder sleeves are short and puffed. The pointed waistline is deep v-shaped, resembling the basque shape. Both the neckline and sleeves were trimmed with lace. The floor-length skirt was very full, containing seven widths of fabric in forward-facing pleats. At her wedding ceremony, Victoria wore a satin train over six yards long, which twelve attendants carried down the aisle (Tobin, Pepper & Willes 32).

Though many contemporary accounts described her wedding ensemble, in her diary, Victoria described it herself:

“I wore a white satin gown with a very deep flounce of Honiton lace, imitation of old. I wore my Turkish diamond necklace and earrings, and Albert’s beautiful sapphire brooch.” (Esher 318)

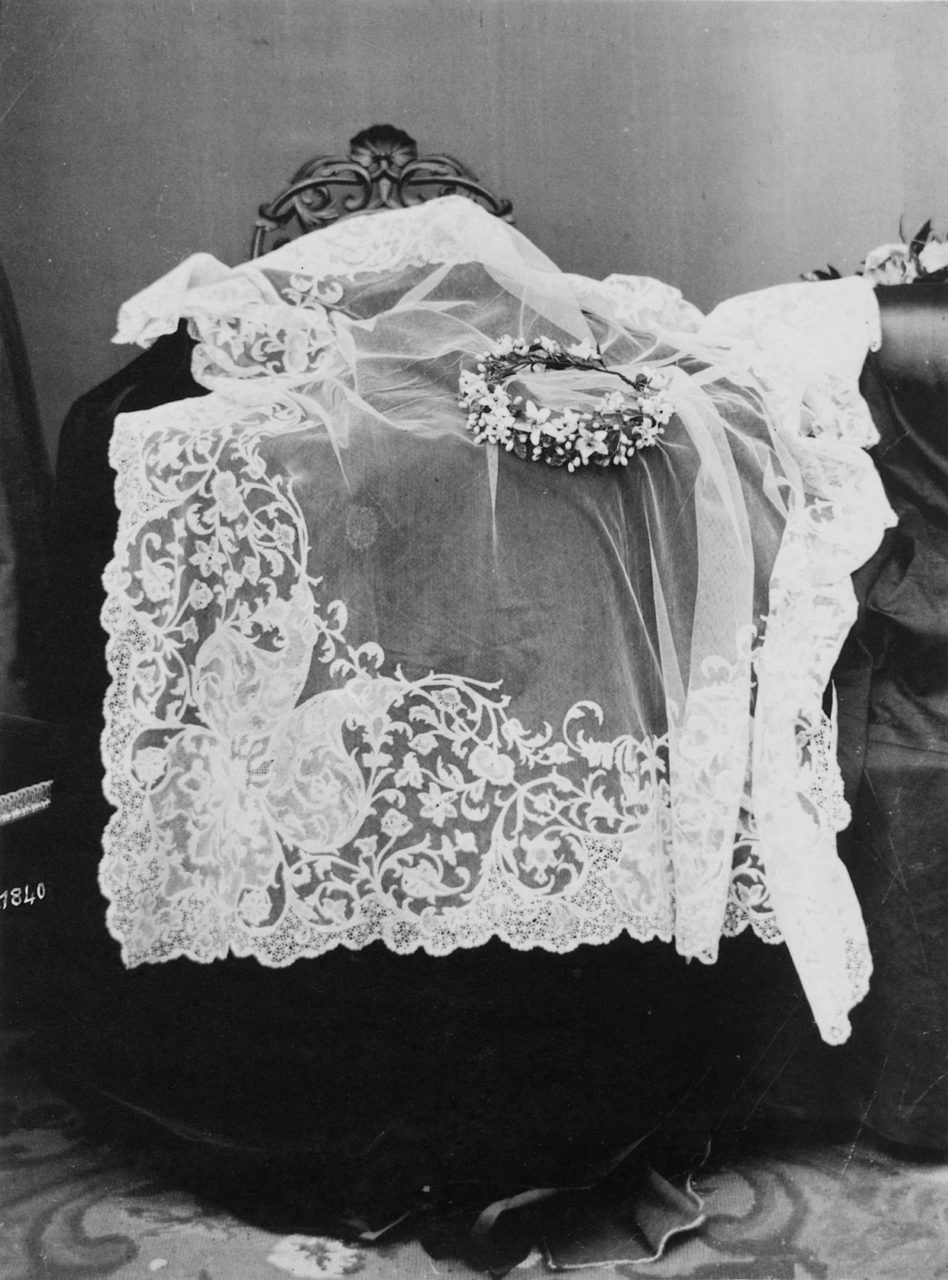

The Queen adorned her skirt, 139 inches in circumference and 37-40 inches in depth, with an exquisite Honiton lace flounce. Due to its fragility, when exhibited, Queen Victoria’s wedding gown is displayed without the flounce (Staniland & Levey 2).

It is important to note that the gown was constructed only of British materials, purposefully patronizing industries that were in decline.

Fig. 1 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 2 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 3 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress on a table, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: British Vogue

Fig. 4 - Mary Bettans (English). Sleeve detail of Queen Victoria's wedding dress, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: National Geographic

Fig. 5 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: Vogue

Fig. 6 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress bodice, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: Queen Victoria's Wedding Dress and Lace

Fig. 7 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress with flounce, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: Queen Victoria's Wedding Dress and Lace

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown. Early photo of Queen Victoria's wedding veil, ca. 1855. Albumen print; 14 x 10.5 cm. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2905584. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria’s wedding dress, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

About the context

Q ueen Victoria’s wedding to Prince Albert in 1840 was as much of a public-relations event as it was a celebration of love. Victoria was completely smitten with her cousin Albert, to whom she proposed. After he accepted her proposal, she confided in her diary:

“[T]o feel I was, and am, loved by such an Angel as Albert was too great delight to describe!” (Woodham-Smith 221)

The young couple’s love also was an ideal opportunity to improve the monarchy’s image. Leading up to this moment, the British monarchy was largely disconnected from the people and did not have a glowing reputation. The monarchy seized the moment by inviting the nation to participate in the heavily romanticized and publicized wedding – displaying Victoria as both Queen and wife for the first time.

Never before had there been such a public royal wedding, with the bride (and Queen) paraded through the streets in a shared, national celebration (Haynes).

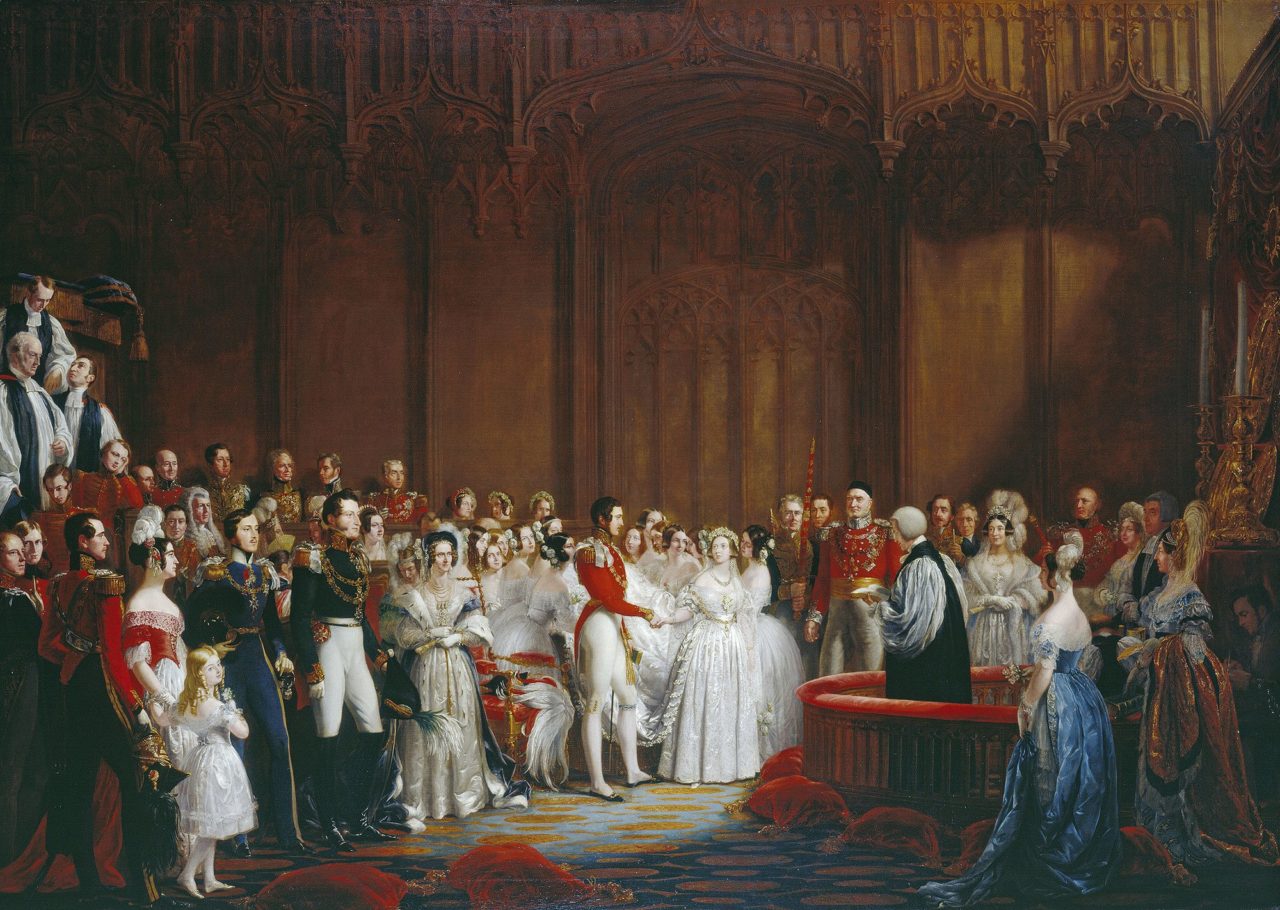

The ceremony occurred on a rainy day, February 10th, 1840, in the Royal Chapel of St. James (Benson & Esher; Greenwood). The typically austere chapel had been transformed into a lavish and decorated scene suitable for great numbers of royalty and nobility (see Fig. 10) (Greenwood). In her diary, Victoria asserted that it had been the happiest day of her life (Cavendish 8).

Fig. 9 - Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). Wedding Anniversary Portrait of Queen Victoria, 1847. Oil on canvas; 53.4 x 43.2 cm. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 400885. Given to Prince Albert by Queen Victoria, 24th February 1847. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 10 - Sir George Hayter (English, 1792-1871). The Marriage of Queen Victoria, 1840-42. Oil on canvas; 195.8 x 273.5 cm. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 407165. Commissioned by Queen Victoria. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 11 - Mrs. Triaud (English). Princess Charlotte's Wedding dress, 1816. Silk, metallic embroidery. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71997. Commissioned by Princess Charlotte for her wedding in 1816. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown (English). Queen Victoria's Great Exhibition dress, 1851. Spitalfields silk. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 74851. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Fig. 13 - Designer unknown (American). Wedding dress, 1837–40. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.7595. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Met

Queen Victoria’s wedding dress was not necessarily the first of its kind, but it was unlike that which any monarch had worn before her. Dr. Jennifer Steadman, curator of the exhibition “Victorian Fashion Crosses the Pond,” believes:

“She wanted to be seen as his wife, so she didn’t wear the red ermine robe of state. She wore white. After that, all representations in Godey‘s and other fashion magazines picked up on that. The white wedding dress became the standard symbol for innocence and romance.” (Dunne)

Julia Baird, author of Victoria The Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire, puts forth another theory – that:

“Victora had chosen to wear white mostly because it was the perfect color to highlight the delicate lace.” (142)

The idea of a white wedding dress was not novel in 1840. While it was not the only acceptable color, white had already been a popular color choice for a wedding gown for centuries (Ginsburg). However, while the English silk and lace undoubtedly made Victoria’s gown magnificent, the color white was simple in comparison to previous royal brides, who typically wore silver or gold as a sign of their royalty (Wackerl 54).

In Agnes Strickland’s contemporary biography of the Queen, published in 1840, she wrote that Victoria was dressed:

“not as a queen in her glittering trappings, but in spotless white, like a pure virgin, to meet her bridegroom.” (209)

In contrast, The Royal Collection Trust is in possession of the gown worn by Princess Charlotte of Wales to her 1816 wedding to Prince Leopold Saxe-Coburg (Fig. 11). The empire-waisted wedding gown is absolutely dazzling, completely covered in silver and gold metallic threads. In fact, the dress worn by Queen Victoria to the Great Exhibition in 1851 was more glitzy than her wedding dress (Fig. 12).

For non-royals, the choice for a bride to wear a white gown to her wedding was a show of wealth (Brennan). In a financial sense, white formal garments were considered impractical for several reasons. For one, keeping a garment white after wear was very difficult (Baird 142). In addition, due to the high cost of textiles and labor, having a new dress made was very expensive. Therefore, when the average woman purchased a new dress, it was not to be worn for once, but many times (Brennan).

The majority of brides in the nineteenth century would re-wear or re-purpose the dress they were married in, so its cut and color needed to be suitable for many other occasions. Such a dress would have been referred to as their “best dress” (Brennan). As such, common colors were russet and brown (Fig. 13). Some women even had their best dress made in colors such as grey or light purple, so that it may be appropriate both to be married in and for mourning.

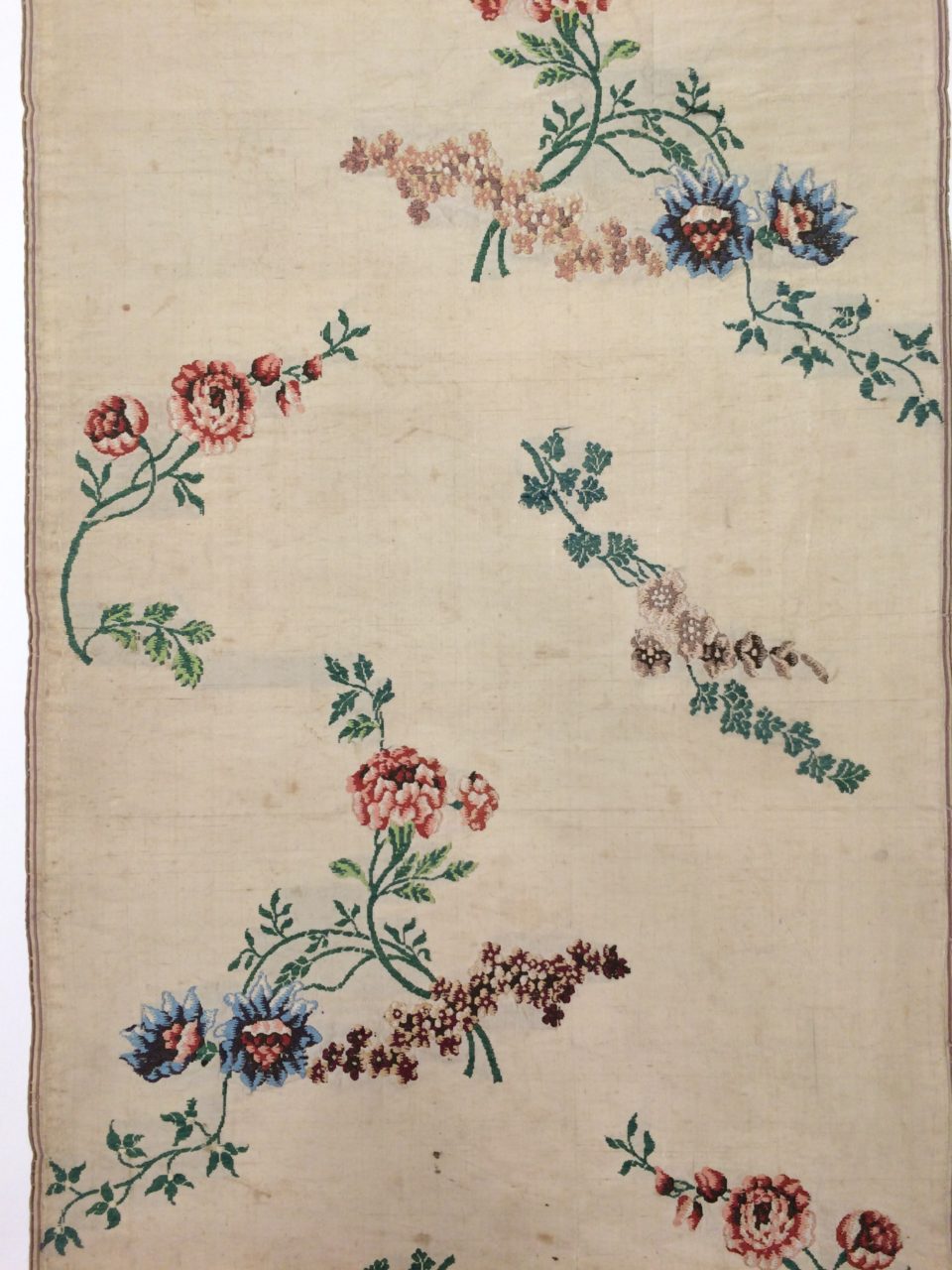

Victoria’s famously white gown was constructed with English Spitalfields silk, as a purposeful show of patriotism, as was the patronage of English lace-makers. Spitalfields, a district in London, became a notable British silk-manufacturing site in the late seventeenth century (The Illustrated Magazine of Art 342-43). A wave of French refugees in 1685 made the city’s silks even more prominent, as French silk weavers brought their knowledge with them. As a result, the Spitalfields silk trade had a very significant and unparalleled rise in the early eighteenth century. As Spitalfields silk became more luxurious, it became coveted and increasingly expensive and fashionable (Fig. 14).

However, that splendor came to an end with the introduction of the power-loom, which made silk-weaving a less specialized profession (Jones 71-96). By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Spitalfields was losing its monopoly on the silk trade (The Illustrated Magazine of Art 342-43).

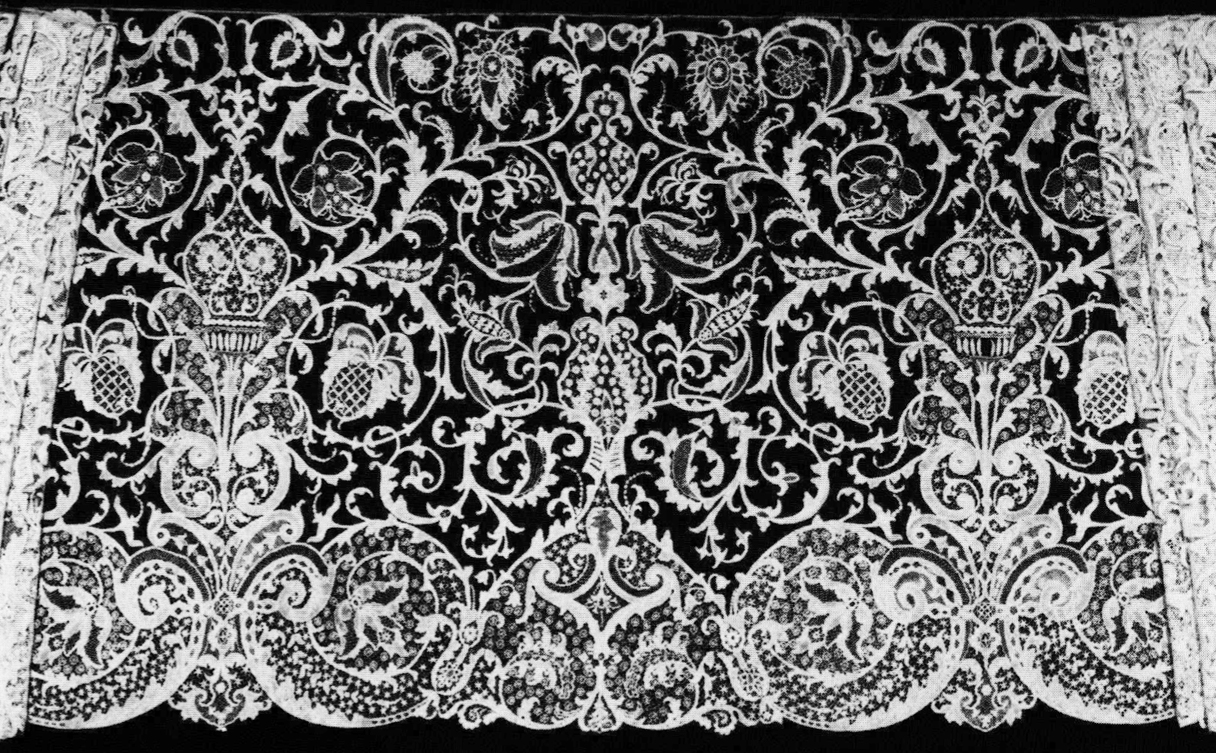

Similarly, the English handmade lace trade was also in decline in the nineteenth century. In an effort to boost the traditional lace-making industry, the crown commissioned William Dyce to design the lace for the Queen’s wedding ensemble (Fig. 15) (Tobin, Pepper & Willes 33). The style of lace was referred to as Honiton, although Victoria’s lace was worked on in a nearby village called Beer. The commission of the Queen’s lace flounce employed two-hundred lacemakers, who were otherwise destitute (Mitchell 156).

Victoria treasured her lace flounce and veil, and continued to wear them to special occasions throughout her life (Staniland & Levey 11-14). She can be seen wearing both in figure 16 – a photograph of Victoria on the occasion of the 1893 wedding of future King George V, which was later used as her Diamond Jubilee portrait.

The bright white vision of Queen Victoria on the happiest day of her life is a stark contrast to what would be her dark sartorial future. Prince Albert passed away in 1861, and Victoria grieved for the remainder of her life. At the time, widows were expected to wear mourning dress for two or three years after their husbands’ passing, making a gradual transition from full to half-mourning. However, Victoria’s chronic depression and prolonged grief cast a forty-year shadow over her wardrobe. It was rumored that when the Queen passed away in 1901, she was buried in her wedding veil (Wackerl 56). In actuality, that is a myth – but the Queen may have been buried with a veil of embroidered mesh (Staniland & Levey 15).

Fig. 14 - England Spitalfields. Skirt panel, ca. 1750–60. Spitalfields silk; 81.3 x 47.0 cm. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 35.126.1. Rogers Fund, 1935. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 15 - William Dyce (Scottish, 1806-1864). Queen Victoria's Lace Flounce, 1839. Honiton lace; (4 x ¾ yards in). Commissioned by Queen Victoria. Source: Queen Victoria's Wedding Dress and Lace

Fig. 16 - W. & D. Downey (English, active 1855-1941). Diamond Jubilee portrait, July 1893. Carbon print; 37.7 x 25.4 cm. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2912658. Commissioned by Queen Victoria. Source: The Royal Collection Trust

Its Afterlife

Q ueen Victoria is sometimes credited with being the sole originator of the white wedding dress, which is untrue. However, it would be accurate to state that her wedding dress contributed to the color’s massive gain in popularity for brides (Baird 142). A combination of new technology, industrialization, media, and admiration for the monarchy all contributed to Queen Victoria’s white wedding dress becoming a lasting tradition.

One such technology was the domination of magazine culture in the early and mid-nineteenth centuries (Garvey 191). A number of nineteenth-century magazines had a target audience of middle-class women, and were a tool for spreading fashions – both through written descriptions and illustrations. Such communications technologies made it possible to popularize the color and style of Victoria’s wedding gown all throughout the Western world, including across the pond; an 1850s American wedding dress is clearly influenced by Victoria’s (Fig. 17).

Almost certainly influenced by Victoria’s wedding gown, in 1849 the popular American women’s magazine Godey’s Lady’s Book asserted:

“Custom has decided, from the earliest ages, that white is the most fitting hue [for brides], whatever may be the material. It is an emblem of the purity and innocence of girlhood, and the unsullied heart she now yields to the chosen one.” (Godey’s 155)

The incredibly influential wedding gown is in the possession of The Royal Collection Trust, and was exhibited in 2002 at “A Century of Queens’ Wedding Dresses 1840-1947” (Fig. 18) and 2018-2020 in “Victoria Revealed” (Fig. 19), both at Kensington Palace in London.

Fig. 17 - Designer unknown (American). Wedding dress, 1856–59. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.346.87a, b. Gift of The New York Historical Society. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 18 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress in “A Century of Queens’ Wedding Dresses 1840-1947”, 1840. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2912658. Source: British Vogue

Fig. 19 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria's wedding dress in “Victoria Revealed”, 1840. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2912658. Source: Yahoo News

References

- Baird, Julia. Victoria The Queen: An Intimate Biography of the Woman Who Ruled an Empire. New York: Random House, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/989514233

- Brennan, Summer. “A Natural History of the Wedding Dress.” JSTOR Daily. JSTOR, September 9, 2017. https://daily.jstor.org/a-natural-history-of-the-wedding-dress/.

- Cavendish, Richard. “Queen Victoria’s Wedding.” History Today, February 2015. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/months-past/queen-victoria’s-wedding

- Esher, Viscount. The Girlhood of Queen Victoria: A Selection from Her Majesty’s Diaries Between the Years 1832 and 1840. Vol. 2. New York: Longman, Green & Co., 1912. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/786201096

- Garvey, Ellen Gruber. “Magazines.” In Dictionary of American History, 3rd ed., edited by Stanley I. Kutler, 191-196. Vol. 5. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2003. Gale eBooks (accessed December 13, 2019). https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2653/apps/doc/CX3401802490/GVRL?u=fitsuny&sid=GVRL&xid=ca86db86.

- Ginsburg, Madeleine. Wedding Dress 1740-1970. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/906442410

- Godey, Louis Antoine, and Sarah Josepha Buell Hale, eds. Godey’s Magazine. Vol. 39. L. S. Godey & Company, 1849. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/2133694

- Greenwood, Grace. Queen Victoria, Her Girlhood and Womanhood, 2004. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/6469.

- Haynes, Suyin. “Historian Lucy Worsley on Royal Weddings, Queen Victoria and the ‘Big Mistake’ People Make About the Past.” Time.com, January 2019, N.PAG. http://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2055/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=134090563&site=ehost-live.

- Jones, S.R.H. “Technology, Transaction Costs, and the Transition to Factory Production in the British Silk Industry, 1700-1870.” The Journal of Economic History 47, no. 1 (1987): 71-96. www.jstor.org/stable/2121940.

- Mitchell, Rebecca Nicole. Fashioning the Victorians: A Critical Sourcebook. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2018. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1085349620

- “Silk and Silk-Weavers.” The Illustrated Magazine of Art 1, no. 6 (1853): 342-43. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20538003.

- Staniland, Kay, and Santina M. Levey. Queen Victoria’s Wedding Dress and Lace. London: Museum of London, 1983. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/473453762

- Strickland, Agnes. Queen Victoria from her birth to her bridal: In two volumes. 1840. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1013361344

- The Royal Collection Trust. “Queen Victoria’s Wedding Dress.” Accessed January 29, 2020. https://www.rct.uk/collection/themes/trails/royal-weddings/queen-victorias-wedding-dress.

- Tobin, Shelley, Sarah Pepper, and Margaret Willes. Marriage à La Mode: Three Centuries of Wedding Dress. London: The National Trust, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/990366252

- Wackerl, Luise. Royal Style: A History of Aristocratic Fashion Icons. Peribo, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/812121139

- Woodham-Smith, Cecil. Queen Victoria: Her Life and Times 1819-1861. Vol. 1. London: H. Hamilton, 1972. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/476244692