About the Look

This 1872 visiting dress features a full bustle silhouette with pleated and gathered ruffles running along the bodice’s opening and the hem of the underskirt (Fig. 1). As with many fashionable ensembles of the time, designer Emile Pingat tried to combine as many elements of fabric manipulation as he could into one garment. Besides the gathering and pleating that covers much of the underskirt, the overskirt was bedecked with dangling fly fringe (Fig. 2), pleated trim, and bows of contrasting fabrics (Fig. 3).

The maroon of the overskirt combined with the light olive underskirt creates a strong color contrast, which was also considered fashionable. Almost every edge in this ensemble is finished with silk bias strips in contrasting colors, bringing the whole gown up to another level (Figs. 4 & 5).

In their 2002 collection catalogue Fashion, The Kyoto Costume Institute states that:

“Many rich Americans were among Worth and Pingat’s clientele, a major Parisian haute couture house at the time, and such designer’s garments were frequently sold in America.” (258)

Fig. 1 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Visiting dress, ca. 1872. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25.200a, b. Gift of Mrs. George D. Cross, 1925. Source: MMA

Fig. 2 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Visiting dress, 1872. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25.200a, b. Gift of Mrs. George D. Cross, 1925. Source: MMA

Fig. 3 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Visiting dress, 1872. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25.200a, b. Gift of Mrs. George D. Cross, 1925. Source: MMA

Fig. 4 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Visiting dress, 1872. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25.200a, b. Gift of Mrs. George D. Cross, 1925. Source: MMA

Fig. 5 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Visiting dress, 1872. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25.200a, b. Gift of Mrs. George D. Cross, 1925. Source: MMA

Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901), Visiting Dress, 1872. Silk. New York; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. George D. Cross, 1925, 25.200a, b. Image: MMA

About the context

Fashions of the early 1870s were often reminiscent of clothing a century before because of the US centennial in 1776; the sides of this overskirt may have been tied up in a nod to a skirt style of the 1770s. It was a fashion that tied the skirt up at two points in the back, often called a ‘polonaise’ but more correctly referred to as ‘retroussée’ (Fig. 6). Caroline Goldthorpe summarizes some of the changes of fashion in the 1870s. In From Queen to Empress (1988) she writes:

“A costume without an overskirt was almost the exception after 1870. The overskirt could be separate, worn with a short bodice, or it could be part of an elongated jacket bodice; both styles were worn with an underskirt of corresponding or contrasting color. One version of this was the polonaise; described at the time as “in the Pompadour style,” it was intended to be a revival of the style of the 1770s, with the overskirt hitched up and secured by buttons at the back.” (46)

In their 1965 book The History of American Fashion, E. Warwick, H. C. Pitz and A. Wyckoff describe this style:

“…a very stylish version of a sacque of about 1770. The overskirt has the lower front corners pulled up underneath the fullness of the skirt in a manner which was described as “rétroussé.” (179)

This retro element is visible at the sides of Pingat’s 1872 gown, in keeping with the fashion of these years.

The sheer variety of extensive trimmings on this gown were the height of fashion; dresses of this early bustle era were often confections of shaped trims, fringe, lace, and anything else the designer could think of (Fig. 7). Goldthorpe further notes:

“Trimmings were lavishly applied to the dress of the 1870s, and gave it much of its form and character. Dresses that had a single skirt either simulated the lines of the overskirt in the trimming or divided the skirt into two halves, the front arranged like an apron in a series of flounces, while a series of different flounces were created at the back.” (46)

Skirts often employed horizontal trimming and flounces, often in contrasting fabrics or textures (Fig. 8). Pingat did not stop at pleats, gathers, and bows, but also ordered contrasting bias, linings, embroidered buttons, and decorative metal parts (Fig. 3). Fine details and finishings were important to dresses in this period; fine fabric alone was no longer enough, and dresses made all in one fabric had to work even harder to stay fashionable (Fig. 9). The contrasting color of the overskirt and underskirt was popular, and more restrained than many examples (Fig. 10), as Lydia Edwards mentions in How to Read a Dress (2017):

“This dress sports a cohesive color scheme, unlike many fashionable ensembles of the time that attempted to meld too many shades in one garment. Contrasting fabrics were also considered fashionable, and this dress is an example of that with two tones of taffeta and silk faille.” (101)

Wide cuffs were also trendy, according to the “New York Fashions” column in an issue of Harper’s Bazar from August 10, 1872:

“Fashionable under-sleeves of linen, to wear with the standing English collar, have wide flaring cuffs. These expand toward the wrist, and are fastened on the outside by two or three large flat linen buttons. As dress sleeves even of the plainest coat shape are rounded, large, and open about the lower part of the arm, the custom of wearing linen cuffs pinned in is no longer practicable, and an under-sleeve is necessary.” (523)

The Pingat gown sports exactly these sleeves, and another coat-sleeve shape can be seen in figure 11. These were shaped sleeves that were made slightly loose, and in the 1860s when they first emerged they were narrow enough at the bottom that detachable cuffs could be used for cleanliness. The coat-sleeves on day dresses of the early 1870s were cut wider, and many afternoon and dinner gowns dispensed with the last few inches of the sleeve entirely.

Other retro elements of 18th century dress also came back into fashion at this time. Engageantes – long, lacy cuffs – were used on gowns that had three-quarter length sleeves, and lent their ruffled, embroidered nature to even the shorter cuffs like those on the Pingat gown (Fig. 5). Designers also brought embroidered covered buttons back into use, and Pingat used them on this gown and others (Figs. 12 & 13). Embroidered buttons were a feature of menswear and court suits in the 18th century, and a logical next step in a period where menswear-inspired touches were beginning to influence women’s ensembles (Fig. 14)

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Scottish). Dress (robe à l’anglaise retroussée), 1775-80. Silk with boning and lined with linen. London: The Victoria & Albert Museum, T.96&A-1972. Given by Miss A. Maishman. Source: VAM

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (probably French). Dress, 1865-70 (probably 1871-73). Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.65.23a, b. Gift of Mrs. William M. Haupt, 1965. Source: MMA

Fig. 8 - Mme. Depret (French). Dress, 1867-71. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.62.35.2a, b. Gift of Miss Elizabeth R. Hooker, 1962. Source: MMA

Fig. 9 - Illman Brothers (engravers) (American). Les Modes Parisiennes (Peterson's Magazine), May 1872. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17509853. Gift of Leo Van Witsen. Source: Watsononline

Fig. 10 - Claude Monet (French, 1840-1926). Camille Monet (1847–1879) on a Garden Bench, 1873. Oil on canvas; 60.6 x 80.3 cm (23 7/8 x 31 5/8 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002.62.1. The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection. Source: MMA

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (English). Dress, 1871-1873. Cotton and silk; length 170.2cm, shoulder to waist: 33cm, hem: 368.3cm, waist: 58.4cm. Manchester: Manchester Art Gallery, 1947.3753. Source: MAG

Fig. 12 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Visiting dress, 1872. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25.200a, b. Gift of Mrs. George D. Cross, 1925. Source: MMA

Fig. 13 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Reception dress, 1883. Silk satin and velvet. Shelburne, VT: Shelburne Museum, 2010-75. Source: Flickr

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (French). Suit, 1774–93. Silk. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 32.35.14a, b. Rogers Fund, 1932. Source: MMA

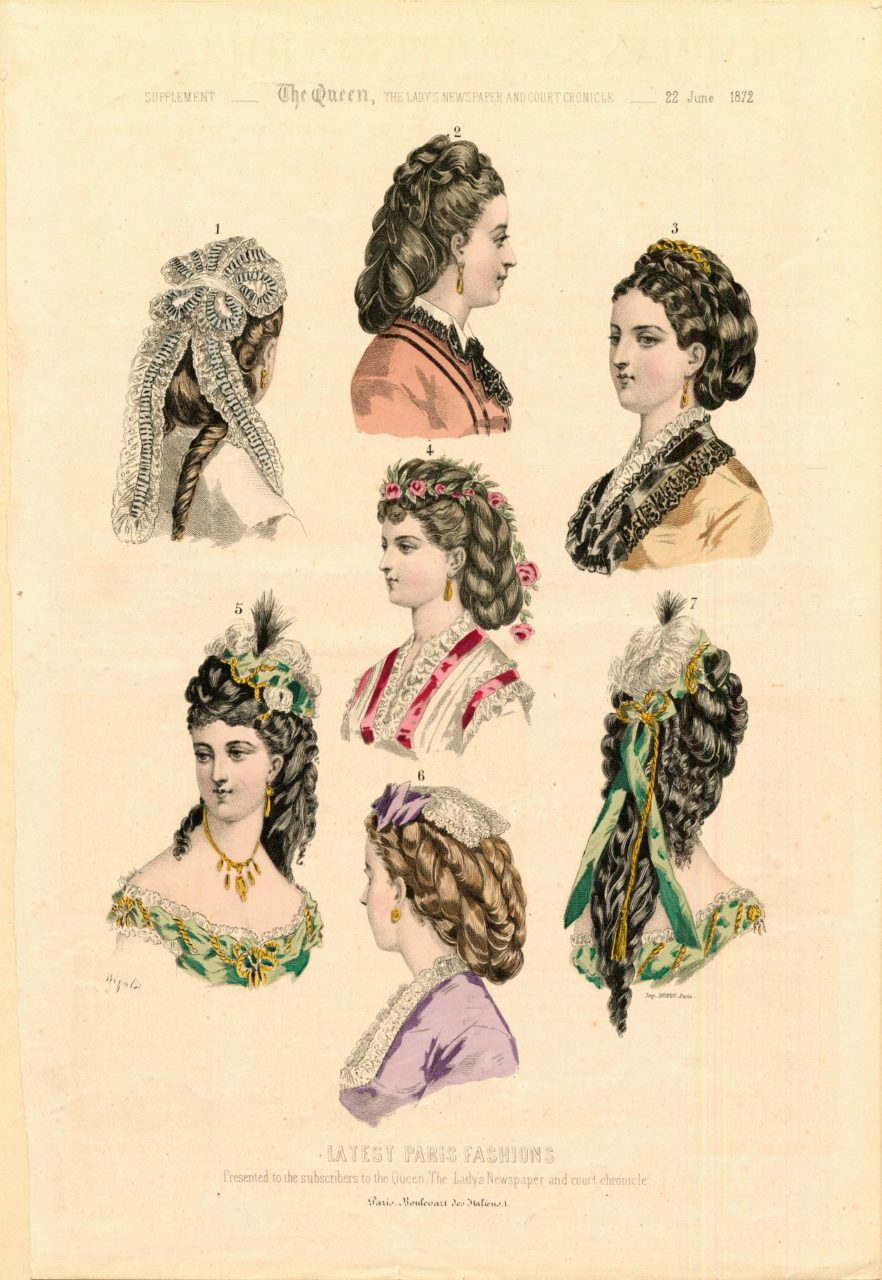

Hair climbed out of the low, round styles of the 1860s and was piled high in complicated braids and ringlets, balancing out the horizontal width of the new gown styles (Fig. 15). The February 1873 issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book notes that coordination is key:

“With these costumes, the shoes, gloves, and flowers in the hair must correspond in color with the dress.” (197)

Just as the fabrics would be embellished with lace and trimmings on every edge, formal hairstyles would be decorated with bits of lace, ribbon, and florals (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15 - Walery (Stanisław Julian Ostroróg) (Polish, 1836-1890). Ms. Emile Menier (Claire Menier), ca. 1873-5. Woodburytype (photoglyptie); height 14.3 cm, width 10.3 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, PHO1986-130-37. Gift of Mr. Jean-Jacques Journet, 1986. Source: Réunion des Musées Nationaux-Grand Palais

Fig. 16 - Dupuy (French, 19th century). Latest Paris Fashions, The Queen, The Lady's Newspaper and Court Cronicle, 22 June 1872. Color lithograph. Claremont, CA: Scripps College, Ella Strong Denison Library, Macpherson Collection, Costume Plates of Myrtle Tyrrell Kirby, fpc00432. Source: Claremont Colleges Digital Library

About the Designer

This dress was designed by Frenchman Emile Pingat, the head designer of the house of Pingat (active 1860-96). Pingat was as highly esteemed as contemporary Charles Worth; however, unlike that of Worth, his name has been largely forgotten today. An 1877 article from Industrial Art mentions him alongside Worth as a man whose opinion on dressmaking is of utmost importance:

“Ask men like M. Worth, who, by the way, is the owner of a house near Mont Valérien,…or M. Emile Pingat, of the Rue Louis le Grand, who is the best mantle-maker now in Paris.” (136)

The brand was known for superb craftsmanship, lavish embellishment, and specialized in elegant outerwear. Figures 18 and 19 are additional examples of his work in the 1870s.

Fig. 18 - Emile Pingat (French, c. 1820-1901). Dinner dress, 1878. Dress of off white silk brocaded in a multicolored floral and vine motif. Chicago History Museum, 1976.270.1a-b. Gift of Mr. Albert J. Beveridge, III. Source: CHM

Fig. 19 - Emile Pingat (French, 1820-1901). Woman's dress: Bodice and Skirt (Reception dress), ca. 1874. Silk with stripes of dark blue satin and tan plain weave; dark blue silk faille; ivory silk embroidery on silk net; ivory and dark blue silk fringe; waist 76 cm (29 15/16 in). Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1938-18-12a,b. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ogden Wilkinson Headington in memory of Ogden D. Wilkinson, 1938. Source: PMA

References:

- “After-Dinner Chat About Dress.” Industrial Art Vol. 1 (July to December, 1877). Google Books. Accessed 8 December 2019. Link.

- “Chitchat on Fashions for February.” Godey’s Lady’s Book Vol. 83 (January 1873). Hathitrust. Accessed 4 February 2020. Link.

- Edwards, Lydia. How to Read a Dress: A Guide to Changing Fashion from the 16th to the 20th Century. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2017. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1126368318

- Fukai, Akiko, and Tamami Suoh. Fashion: a History from the 18th to the 20th Century. London: Taschen, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/858116273

- Goldthorpe, Caroline. From Queen to Empress: Victorian Dress 1837-1877. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/18625302

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar Vol. 5, No. 32 (August 10, 1872): 523. HEARTH (Home Economics Archive: Research, Tradition, History). Accessed 8 December 2019. Link.

- Warwick, Edmund, H. C. Pitz, and A. Wyckoff. The History of American Dress: Early American Dress: the Colonial and Revolutionary Periods. New York: B. Blom, 1965. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/983816708