This lush purple velvet dress designed by Elizabeth Keckley for Mary Todd Lincoln features both an evening and day bodice paired with a wide crinoline skirt. The ensemble, worn in 1861-62 while Lincoln was First Lady, reflects fashionable dress trends of the time.

About the Look

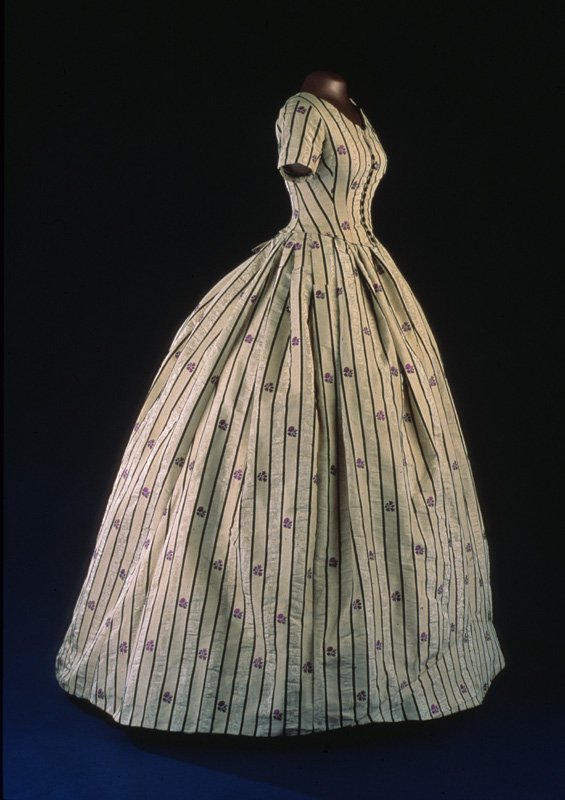

Mary Lincoln’s early 1860s violet velvet dress is currently held in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. It is a three-piece set that includes a day bodice (Fig. 1), as well as an evening bodice (Fig. 2), paired with a full bell-shaped crinoline skirt. It should be noted that due to the amount of fabric that the skirts required during this time, it was common for women to have both a day bodice and evening bodice that matched the skirt (see also Figs. 14-15 below). Moreover, as the Smithsonian notes, although it was important for Lincoln to dress in a way befitting her position as First Lady, she also didn’t want to be seen as flaunting money as the United States was embroiled in the Civil War at this time.

Both bodices and the skirt employ purple velvet as the main dress fabric with the seams highlighted with white satin piping. The day bodice (Fig. 1) has full-length sleeves, seven square mother-of-pearl buttons down the center front and a high neckline circled by a white lace collar that was “of the period, but not original to the dress” (Smithsonian). The bodice comes to a V-shaped point below the waistline; its edges as well as the seams that shape the bodice are highlighted with white piping. The sleeve cap is off-the-shoulder and is adorned with small wings also adorned with white piping. It is clear that in addition to the collar being added, the sleeves of this bodice were altered as well. There are different velvet patches along the sleeves that are a much lighter bluish purple. The right sleeve is almost completely re-done as well with some smaller areas on the left sleeve, however it is unclear when these changes were made and why (perhaps they were part of the museum conservation process). The rear of the day bodice features flattering piping creating the illusion of an even slimmer waist and terminates in a masculine-style jacket tail (Fig. 3)

The evening bodice laces up the back (Fig. 4) and features a low neckline with off-the-shoulder sleeves. The sleeves consist of dangling cream chenille trim at the sleeve cap, then poofs of cream tulle, followed by black lace that has a cream trim at the edges (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln's dress - day bodice, Winter, 1861-1862. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Bequest of Mrs. Julian James. Source: Smithsonian

Fig. 2 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln's dress - evening bodice, Winter, 1861-1862. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Bequest of Mrs. Julian James. Source: Smithsonian

Fig. 3 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln's dress - day bodice rear view, Winter, 1861-1862. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Bequest of Mrs. Julian James. Source: Smithsonian

Fig. 4 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln's dress - evening bodice rear view, Winter, 1861-1862. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Bequest of Mrs. Julian James. Source: Smithsonian

Fig. 5 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln's dress - evening bodice rear view, Winter, 1861-1862. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Bequest of Mrs. Julian James. Source: Smithsonian

Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Lincoln’s Dress, 1861-1862. Violet velvet with satin, lace, and mother-of-pearl buttons. Washington: Smithsonian National Museum of American History, 70138. Source: Smithsonian

About the context

This garment was made by Elizabeth Keckley (Fig. 6) and worn by First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln in 1861-62. As April Calahan and Cassidy Zachary explain on the “Dressed: The History of Fashion” podcast, Keckley, who was the primary dressmaker and close friend to the First Lady at this time, went through terrible hardships to achieve that position. Keckley was born a slave to her father, Armisted Burwell, in 1818. By the time she was an adult, she was enslaved to her half-sister and her husband, the Garland family. Over these years, Keckley acted as the primary supporter of the Garland family as she was an established dressmaker for the elites in St. Louis. After 12 years of working for the Garland family Keckley was given the money to free herself and her son, George, by a valued client. Elizabeth and George were able to move to Washington DC where she set up shop. She designed dresses for many political wives including Mary Anna Custis Lee, Varina Davis, and Adele Cutts Douglas, until she was introduced to Mary Lincoln. Keckley then became Lincoln’s favorite designer and over the years became a close confidant of the Lincoln family (Calahan and Zachary).

The Smithsonian National Museum of American History notes that the dress was worn by Mary Lincoln “during the Washington winter social season in 1861-62” (Smithsonian). This would be at the end of Lincoln’s first year as President, as he served from 1861 until 1865 when he was assassinated. After President Lincoln’s assassination, Mary went into mourning and either sold or gave away her clothing. The Smithsonian reveals that “her cousin, Elizabeth Todd Grimsley, received this purple velvet ensemble.”

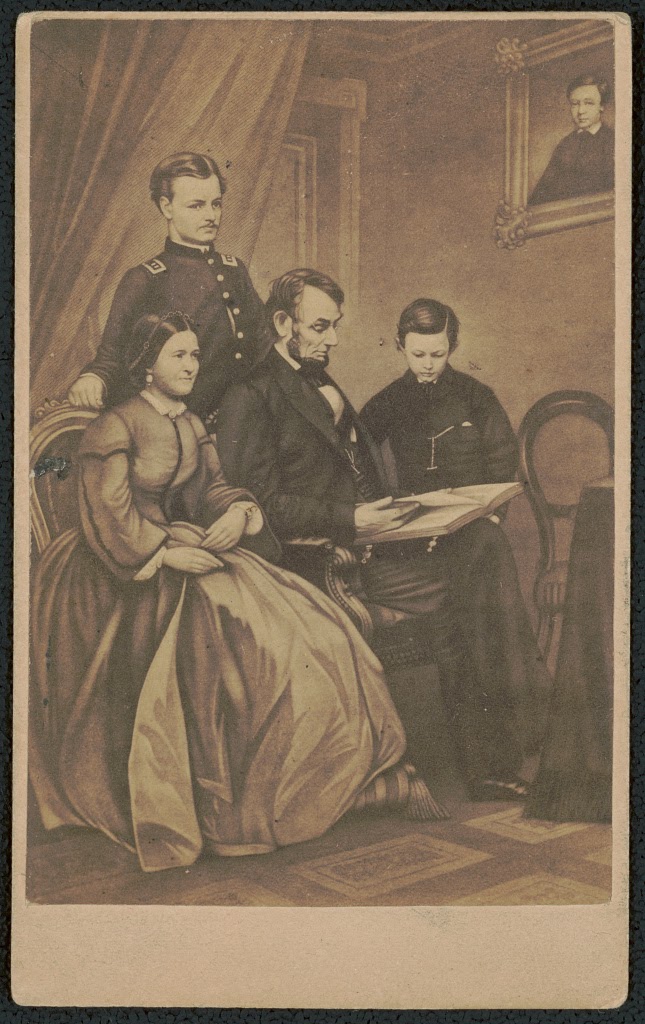

An family portrait painted by Frederic Schell ca. 1865 shows Mary Lincoln wearing a very similar style of day dress (Fig. 7), alongside Abraham Lincoln reading a book, surrounded by their sons Robert Todd Lincoln and Tad Lincoln, with a portrait of their son Willie Lincoln (deceased) hanging on the wall. The image that the Lincoln family presented was important and images of them were frequently reproduced, just as this painting was photographed and sold as a collectible carte-de-visite photograph. With the Civil War under way, it was vital that the Lincoln family appear to be an ideal family.

Fashion was a part of creating that image. As Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine explained in a January 1862 article on simplicity of dress:

“A modest woman will dress modestly: a really refined and intellectual woman will bear the marks of careful selection and faultless taste.” (60)

Thus it should perhaps not be surprising to find all the elements of Lincoln’s ensemble to be aligned to the tastes and trends of the day. The silhouette and especially the skirt shape with a slight train at the back are fitting for the time period as “By about 1862, the [crinoline] cage began to swing toward the back, becoming pyramid-shaped, the silhouette for the majority of the decade” (Franklin).

Fig. 6 - Photographer unknown. Elizabeth Keckley, ca. 1861. Washington D.C.: Moorland Spingarn Research Center at Howard University. Source: The White House Historical Association

Fig. 7 - Frederic B. Schell (American, 1838-1905). Lincoln Family, 1865. Photograph after a painting; 10 x 6 cm. 1278. Source: Library of Congress

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown (American). Winter Walking dress, Godey's Lady's Book and Magazine, vol. 64 (January 1862): 17. Source: HathiTrust

Fig. 9 - Photographer unknown (American). Woman in day dress, 1861-1865. Source: The Barrington House

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (French). Fashion Plate, June 1861. Source: Le Follet

A January 1862 fashion plate (Fig. 8) from the American fashion magazine, Godey’s Lady’s Book, features a dark winter walking-dress with white cording at the seams and narrow sleeves that looks almost identical to Lincoln’s day dress. The caption reads: “Made of rich reps. The dress is gored, and the seams covered by a thick silk cord” (17). Rep is a ribbed, durable medium to heavy fabric, typically woven of wool. The heavy velvet of Lincoln’s has a similar visual effect, though it is more luxurious, as is suitable for dress that must also serve as winter evening wear. The fashion plate is in black and white which makes it hard to know what color the dress was, but it can be inferred that it was a darker color due to the dark engraving. A early 1860s photograph of an unknown woman in a dark day dress from this same period also features white piping or cording highlighting the dress’s seams and pockets (Fig. 9), suggesting the popularity of this design detail at the time.

A June 1861 fashion plate depicting two women and a child outside (Fig. 10) from the French fashion magazine Le Follet also features a black cloak accented with white piping like that on Lincoln’s dress (notably the dress it tops is also purple). The dark solid color fabric and simple white piping are important trends that Keckley adopted when creating the ensemble. That Mary Lincoln’s dress so closely resembles these fashion plates demonstrates how attuned to trends–or even trend-setting–Keckley was as a dress designer.

Fig. 11 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Mary Todd Lincoln's Gown and Cape, 1862. Chicago: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-066126 and ICHi-066122. Source: Chicago History Museum

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode illustrée, vol. 20 (May 1861). Source: La Mode illustrée

Lincoln’s dress was not preserved with an outer coat, but other dresses for which made Keckley made coordinating cloaks (Fig. 11) and the weather conditions of Washington in the winter months suggest that Lincoln would have worn both the day and evening bodices with a similar cape or cloak.

The violet color Keckley used was seen as a great challenge at this time as Mrs. Merrifield explains in a Godey’s article, “The Use and Abuse of Colors in Dress” (January 1862):

“Of all colors, perhaps the most trying to the complexion are the different shades of lilac and purple. The fashionable and really beautiful mauve and its varieties are of course included in this category.” (73)

Due to the paleness of white American’s skin color, certain colors like violet, red and yellow did not easily complement the complexion. That being said, purples appeared frequently in the color plates of important, trend-setting French fashion magazines like La Mode illustrée and Le Moniteur de la mode throughout 1861 (Figs. 10, 12), marking it as one of the year’s most fashionable colors. A plate in La Mode illustrée from May 1861 (Fig. 12) features a very similar vivid purple day dress, paired with a white collar, that buttons down the center front and ends in divided V-shaped tabs, just as Lincoln’s dress does.

Not only was purple fashionable, but, as Jill Morton explains, violet is also known as a color that “symbolizes nobility… [and] a color of mourning.” We can infer that Lincoln was perhaps wearing violet to represent symbolic mourning due to the Civil War which had recently begun. Notably another of Keckley’s early 1860s dresses for Lincoln was white accented with violet flowers (Fig. 13 – read an analysis of that dress here!).

While Lincoln’s purple velvet day dress may seem somewhat plain, simple dresses at this time were popular and considered elegant, as a Godey’s article entitled “Simplicity of Dress” (January 1862) remarks:

“Female loveliness never appears to so good advantage as when set off with simplicity of dress. No artist ever decks his angels with towering feathers and gaudy jewelry…. These tinselries may serve to give effect on the stage, or upon a ball-room floor, but in daily life there is no substitute for the charm of simplicity.” (60)

Fig. 13 - Elizabeth Keckley (American, 1818-1907). Evening dress for Mary Todd Lincoln, April 1862. Moiré silk taffeta. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Source: National Museum of American History, Behring Center

Fig. 14 - Designer unknown (American). Day dress worn by Jessie Benton Fremont, 1860s. Faille moire silk, tulle, chantilly lace, and carnival glass buttons. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2005.618.1-3. Museum purchase with funds donated by the Textile and Costume Society, Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

Fig. 15 - Designer unknown (American). Evening dress worn by Jessie Benton Fremont, 1860s. Faille moire silk, tulle, chantilly lace, and carnival glass buttons. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 2005.618.1-3. Museum purchase with funds donated by the Textile and Costume Society, Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Source: Museum of Fine Arts

As the quotation above suggests, exceptions were made for evening dress, as the ballroom floor called for more sparkle than did daily life. Thus Keckley’s evening bodice design has all the lace, tulle and fringe that such an occasion called for. Indeed, in its profusion of decorative sleeve elements, it could hardly be called simple.

The expected contrast between the simplicity of day dress and the elaborateness of evening dress can be seen in a similar set of garments held by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (Figs. 14-15). The day and evening dresses in this case are made of purple moiré silk, but share many design elements with those designed for Lincoln. These dresses were worn by Jessie Benton Frémont, another political wife and prominent abolitionist (Snyder). The garments feature additional design details like the black lace trim on the day bodice and purple bows on the crinoline skirt, but are aligned with the tastes of the time period. The evening bodice (Fig. 15) includes black and cream lace trim as well as tulle sleeves, and the bodice comes to a V-shaped point just as Lincoln’s does. As was typical in the 19th century, the evening bodices are much more detailed and showy than the day bodices.

Thus Keckley’s savvy designs for Lincoln follow the trends of the season as well as aligning with the dress choices of other American political wives at this important moment in American history.

References:

- Calahan, April, and Cassidy Zachary. “Elizabeth Keckly: ‘Thirty Years a Slave’ to White House Dressmaker.” Broadcast. Dressed: The History of Fashion. iheartradio, April 10, 2018. https://www.iheart.com/podcast/105-dressed-the-history-of-fas-29000690/episode/elizabeth-keckly-thirty-years-a-slave-29168915/

- “Elizabeth Keckley: White House Dressmaker, Author, and Civil Activist.” Chicago History Museum, May 26, 2020. https://www.chicagohistory.org/elizabeth-keckley-white-house-dressmaker-author-and-civil-activist/.

- Franklin, Harper. “1860-1869.” Fashion History Timeline, December 27, 2019. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1860-1869/.

- “Mary Lincoln’s Dress.” National Museum of American History. Accessed June 12, 2020. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1359703.

- Merrifield, Mrs. “The Use and Abuse of Color in Dress”. Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine vol. 64 (January 1862): 73. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015016441498&view=1up&seq=77

- Morton, Jill. “Purple.” Color Matters. Accessed June 12, 2020. https://www.colormatters.com/the-meanings-of-colors/purple.

- “Simplicity of Dress”. Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine vol. 64 (January 1862): 60. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015016441498&view=1up&seq=64

- Snyder, Rachel. “Jessie Benton Fremont: Civil War Stateswoman.” Virginia Center for Civil War Studies, 2015. https://civilwar.vt.edu/jessie-benton-fremont-the-civil-war-stateswoman/.

- Way, Elizabeth. “Elizabeth Keckly and Ann Lowe: Recovering an African American Fashion Legacy That Clothed the American Elite” (125), Fashion Theory, 19:1 (2015), 115-141, DOI: 10.2752/175174115X14113933306905