Paul Cézanne based his painting, The Conversation (1870-71), on a fashion plate from La Mode Illustrée, which confirms that his figures are presented in fashionable dress. Through this work he indirectly comments on the greater social issues of late nineteenth century France, as well as reflects a dark moment in French politics and his own mental state.

About the ARTWORK

Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) was an influential French painter working during the later half of the nineteenth century. In Grove Art Online (2003), Geneviève Monnier explains how the artist came under the influence of Impressionism in the 1870s, notably drawn to the work of Camille Pissarro. Cézanne went on to participate in the First (1874) and Third (1877) Impressionist Exhibitions (Monnier). In 1870, he painted The Conversation, also known as La Conversation in French or Women In A Garden (Dorival, IV). The title is often critiqued as being dissonant — argued by Fine Art America (2019), stating:

“Neither woman looks to be talking to the other; the one has her face turned away and is leaning away from her companion, the other looks distracted and has her hand half-covering her lips. Both men have their backs turned.”

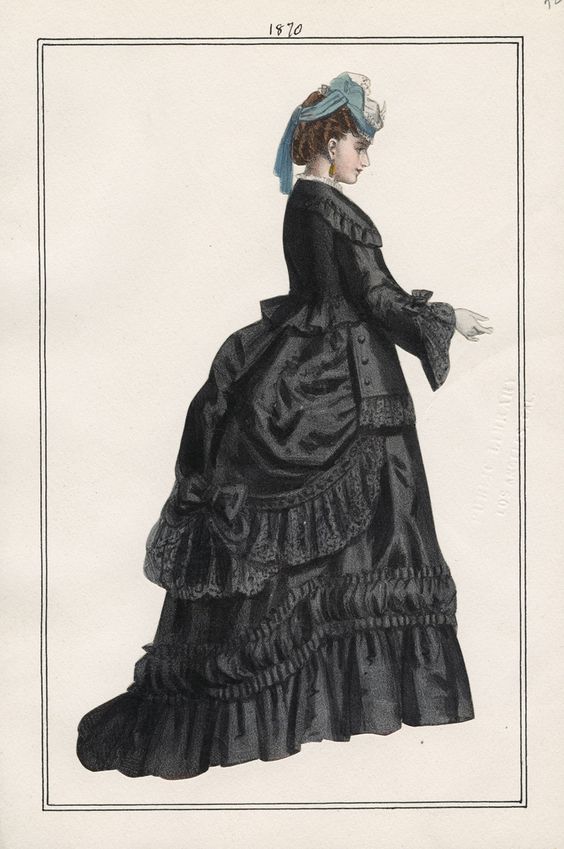

Fig. 1 - Adele-Anaïs Colin Toudouze (French, 1822-1899). La Mode illustrée, July 31, 1870. Source: NYPL Digital Collections

The painting is based on a July 31, 1870 fashion plate from La Mode Illustrée (Fig. 1). While minor style changes were seen in Cézanne’s adaptation, the figures’ posing and fashions remain notably similar. In the text The World of Cézanne (1968), author R.W. Murphy writes:

“Cézanne placed his sisters, Marie and Rose (wearing their own gowns), in the same poses as the women in the print, but added two of his friends in the background to add interest to the scene.” (410)

The inclusion of the two male figures may have served a greater purpose beyond creating a more dynamic composition. Françoise Tétart-Vittu in the “Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity” catalogue (2012) notes: “their presence subverts the typical female universe pictured in fashion plates” (69). Some historians have drawn a connection between the scene presented by Cézanne and the notable concern with late nineteenth century courting practices — placing a clear emphasis on the male/female divide. This decision is analyzed further in the essay, “The Emperor’s Last Clothes: Cézanne, Fashion and ‘L’annee Terrible’” (2006), in which André Dombrowski claims:

“The details Cézanne chose to dramatise add a sexual charge to the print: strips of fabric on the standing woman’s skirt look like phalluses; a black lace scarf over a white dress presents itself as pubic hair. Removed from the exclusively female realm of fashion, the transformed print evokes urban images of not so genteel flirtation.” (590)

Fig. 2 - Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906). La Promenade, 1871. Oil on canvas; 58.2 x 45.8 cm. Private Collection. Source: Artnet

Fig. 3 - Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906). Two Women and Child in an Interior, 1861. Oil on canvas; 91 х 72 cm. The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Source: Pushkin Museum

Fig. 4 - Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906). The Conversation (Detail), 1870-71. Oil on canvas; 92 x 73cm. Source: Christie's

When analyzing the demure scene of modern life that Cézanne depicts, the sexual implications Dombrowski supports appear to be far-fetched, as the suggestive imagery that author claims to see seems merely to translate into paint details of the original print. Reportedly Cézanne experienced a depressive episode during the 1870s. This period of his artistic career was fueled by an effort to distract himself from negative thought patterns, rather than the joy of creativity. In The World of Cézanne (1968), R.W. Murphy discusses: “In the first stage, which lasted until the early 1870s, Cézanne was groping for a means to express his inner agitations” (41). Cézanne (2003) references his artwork produced just before 1870, with author Hajo Düchting revealing:

“The pictures Cézanne painted at that time constitute a veritable collection of human fears and horrors. Scenes of murder and rape alternate with gloomy visions… Temptations that offer no escape are followed by collective or private orgies.” (49)

Learning of Cézanne’s struggles with mental health in this period gives the viewer a deeper perspective into the artist’s mindset.

The social context of this artwork is also important to consider, according to Christie’s (2018), with Keith Gill explaining how The Conversation was created “at precisely the moment when [Cézanne’s] country had become engulfed in a disastrous war with Prussia and he himself was in hiding from being drafted into the French army.”

The Conversation is not the only painting he created based on fashion plates. He painted two others titled La Promenade (Fig. 2) and Two Women and a Child in an Interior (Fig. 3). La Promenade is most similar to The Conversation as both show two women on a social outing in a garden setting. These ensembles are appropriately accessorized with a parasol and gloves. Both Two Women and a Child in an Interior and The Conversation juxtapose a day and evening look.

Dombrowski states: “La Mode Illustrée was among the few Parisian periodicals that continued to appear uninterruptedly throughout the Siege and Commune” (586). An important change to take note of in Cézanne’s rendition is the addition of a French tricolor flag (Fig. 4) that flutters from a domed rooftop in the distance. This small detail gives the scene a politicized edge. While the French flag may not be a focal point of the painting, Dombrowski notes that during the 1870s: “in the world of art, painting blue, white and red in close proximity was no longer possible without making a specific gesture towards nationalism.”

Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906). The Conversation, 1870-71. Oil on canvas; 92 x 73 cm. Source: Christie’s

About the Fashion

“Bustled dresses of this period were frothy confections, with layers of ruffles, pleats, and gathers. Many featured looped overskirts or long bodices that were draped up over the hips; these were often referred to as ‘polonaise’ style dresses.” (Franklin)

This essay also touches on popular sleeve styles: “In the first years of the decade, the bell-shaped sleeves of the 1860s continued to be seen” (Franklin). This 1870 fashion plate (Fig. 5) illustrates the popular stylistic elements of the time — higher than natural waistlines, lower sloped shoulders with sleeves extending into wide cuffs, and bodices featuring basques; peplum extending past waistline and resting ontop of bustle, in the back. The fabric of the skirt is also treated in tiers, with the hem acting as a large ruffle.

While the womens’ garments in Cézanne’s painting reflect late nineteenth century fashionable ideals, his painterly style abstracts some of the more elaborate detailing (Fig. 6). The embellishments often utilized by dressmakers are discussed in an April 1, 1871 article titled “New York Fashions: The Apron-Polonaise” in Harper’s Bazar:

“It may be trimmed with passementerie and fringe, or lace. The trimming passes down the front and crosses on the apron, making a very dressy tablier. Some polonaises are provided with over-sleeves in the flowing oriental style.” (194)

Fig. 5 - Unknown. 1870 Fashion Plate, 1870. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 6 - Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906). The Conversation (Detail), 1970-71. Oil on canvas; 92 x 73 cm. Source: Christie's

An example of this detail is illustrated by a 1873 La Mode illustrée fashion plate (Fig. 7) that features women wearing garments with ruffled skirts, paired with decorative bows placed at the top of the bustle. The hue of the light blue fabric used in the dress of the woman on the left is similar in color to the blue used for the lefthand figure in The Conversation. The two two-toned layering seen in the dress on the right also has similarities to Cézanne’s second figure (on the righthand side). Despite these similarities, the abstraction of garment trimmings (key elements of 1870s fashion) in the painting takes away from the fashionability of his rendition. This is likely not due to a lack of understanding of stylistic trends, on his part, but a choice made in pursuit of a simpler and looser painting style. Considering the social context, it could also be assumed that this instance of simplified fashion has a connection to the social ramifications of war that Paris was enduring at the time.

Carefully paired accessories were essential to outerwear, like depicted in The Conversation (Fig. 8), as a May 27, 1871 article titled “New York Fashions: Traveling Dresses” in Harper’s Bazar notes:

“The parasols used this year are umbrellas in size, large enough for protection against sun and shower. They are of silk or pongee, with merely a band of a darker shade bordering the edge, or else are deeply fringed… Small parasols of white silk under black lace covers are the choice for ceremonious visiting and other dressy occasions.” (323)

This quote about parasols connects to the white one pictured in The Conversation, held by the woman on the left. The parasol’s inclusion in both fashion plate and later painting reflects the desirability of the accessory at the time, the appropriate selection of color, and the object’s significance to the setting/situation.

A 1871 portrait photograph by William Notman (Fig. 9) also supports the fashionability of the garments featured in Cézanne’s painting. The model’s garment has the same off-the-shoulder, “bertha” draping on the sleeves (as seen on the dress worn by the painted woman on the right). The dress also features an almost apron-polonaise over a fuller skirt underneath. The bodice is also form-fitting — further accentuating the wearer’s waist at a higher than natural point.

Paul Cézanne’s The Conversation depicts figures in fashionable dress, while also injecting a political charge to the standard fashion imagery reflecting the turmoil of the time.

Fig. 7 - Hélöise Leloir (French, 1819-1873). La Mode illustrée, 1873. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - Paul Cézanne (French, 1839-1906). The Conversation (Detail), 1870-71. Oil on canvas; 92 x 73 cm. Source: Christie's

Fig. 9 - William Notman (Scottish, 1826-1891). Albumen Print, 1871. Silver salts on paper mounted on paper albumen process; 17.8 x 12.7 cm. Montreal, QC: McCord Museum, I-62473.1. Source: McCord Museum

References:

-

Dombrowski, André. “The Emperor’s Last Clothes: Cézanne, Fashion and ‘L’année Terrible.’” The Burlington Magazine 148, no. 1242 (2006): 586–94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20074554

- Dorival, Bernard. Cézanne. Paris: P. Tisné, 1948. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/42761015

- Duchting, Hajo. Cézanne. Los Angeles: Taschen, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1245645428

- Franklin, Harper. “1870-1879.” Fashion History Timeline, November 11, 2019. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1870-1879/.

- Gasquet, Joachim. Joachim Gasquet’s Cézanne: A Memoir with Conversations. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/24120337

- “La Conversation.” Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), 2018. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6155250.

- Monnier, Geneviève, and André Dombrowski. “Cézanne, Paul.” Grove Art Online.

2003; Accessed 8 May. 2022. https://www-oxfordartonline-com.libproxy.fitsuny.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000015638. - Murphy, R. W. The World of Cezanne: 1839-1906. Amsterdam: Time-Life Books, 1968. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966021934

- “New York Fashions: The Apron-Polonaise.” Harper’s Bazar vol. 4, no. 13 (April 1, 1871): 194-195 https://www.proquest.com/magazines/new-yorkfashions/docview/1832463106/se-2?accountid=27253.

- “New York Fashions: Traveling Dresses.” Harper’s Bazar vol. 4, no. 21 (May 27, 1871): 323 https://www.proquest.com/magazines/new-york-fashions/docview/1832464563/se-2?accountid=27253.

- “The Conversation by Paul Cezanne.” Fine Art America, April 17, 2019. https://fineartamerica.com/featured/the-conversation-paul-cezanne.html

- Tétart-Vittu, Françoise. “Who Creates Fashion?” In Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity, ed. Gloria Lynn Groom, 63-77. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/983756924