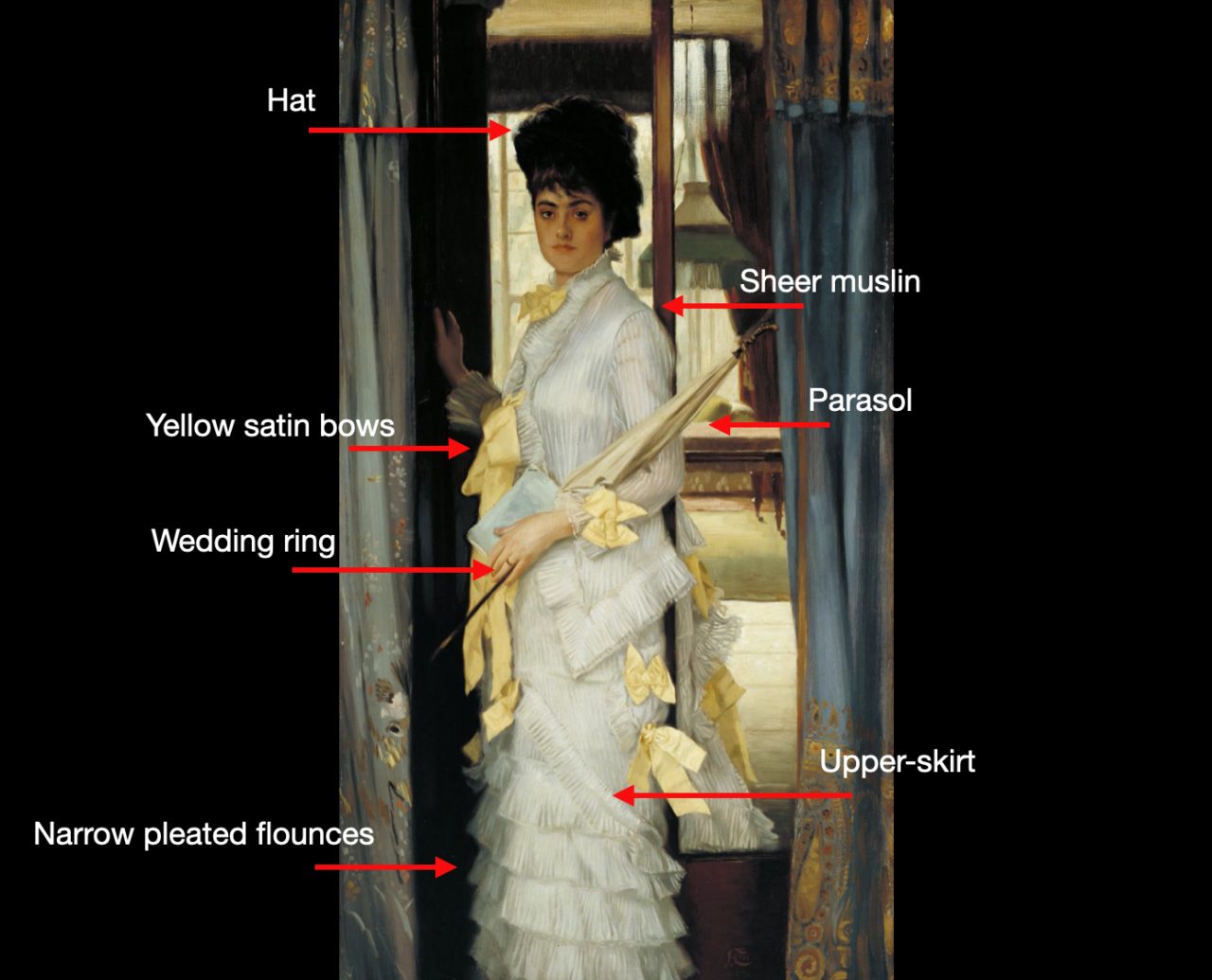

In Tissot’s Summer, a woman stands in front of a room inviting someone in, or perhaps leaving. She wears a sheer muslin dress trimmed with yellow bows, which was considered fashionable for the time. Despite it being contemporary fashion, Tissot received criticism about his works that featured this dress at the 1877 Grosvenor Gallery. Over the years, Tissot repeats this dress in multiple paintings not only for its fashionability, but also for its artistic challenge.

About the Artwork

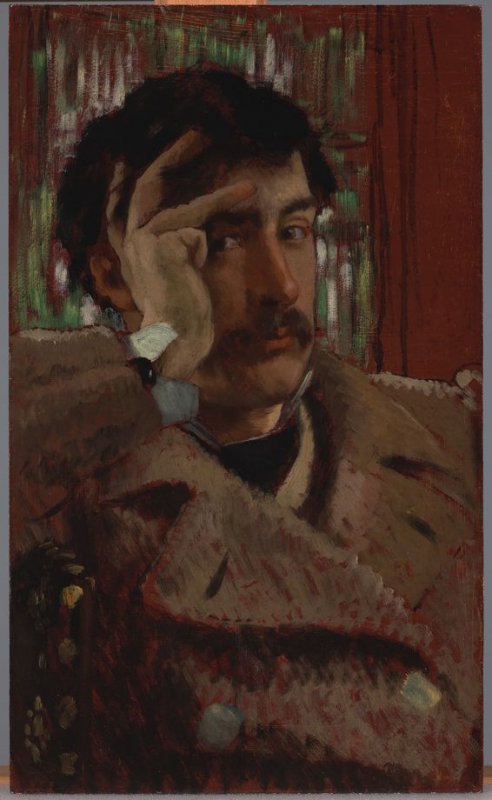

Summer, sometimes referred to as A Portrait, was created in 1876 by French painter and printmaker James Tissot (Fig. 1). Tissot was born on October 15, 1836 in Nantes, France into a family of textile merchants. Twenty years later, around 1856, Tissot moved to Paris to study under Louis Lamothe and Hippolyte Flandrin. In 1859, he made his debut at the Paris Salon. He would continue to exhibit at the Salon until his move to London in 1871. Tissot lived in London where he gained fame and regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy, until the death of his partner, Kathleen Newton, in 1882 when he moved back to Paris (Misfeldt).

Tissot was famous for his portraits and genre paintings depicting modern life, which typically showed his models in fashionable dress. In Summer, Tissot leaves much interpretation up to the viewers. It is unclear whether his model is inviting someone in or leaving. Her social status is also in question, as she is standing in front of a billiards’ room, which was typically associated with men. This ambiguous type of painting was not uncommon for the time; in fact, the Summer gallery label at the Tate notes:

“This genre of painting, with open-ended narratives, widely appealed to Victorians at this time.” (The Tate)

Summer was exhibited at the 1877 Grosvenor Gallery along with nine other works by Tissot. Despite Tissot’s fame and popularity, critics were sometimes hostile to the works on display. For instance, in July 1877, Irish playwright Oscar Wilde wrote in the University Magazine:

“What a gap in art there is between such as picture as ‘The Banquet of the Civic Guard,‘ in Holland, with its beautiful grouping of noble-looking men… and Mr. Tissot’s over-dressed, common-looking people, and ugly, painfully accurate representation of modern soda-water bottles!” (125-126)

After the completion of the painting, Tissot created a drypoint which reversed the composition, while mimicking the background and clothing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1901). Self Portrait, ca. 1865. Oil on panel; 49.8 x 30.2 cm (19 5/8 x 11 7/8 in). San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1961.16. Museum purchase, Mildred Anna Williams Collection. Source: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco

Fig. 2 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Portrait of Miss L...,or A Door Must Be Either Open or Closed, 1876. Drypoint on laid paper; only state; plate: 38.8 x 21.6 cm (plate: 15 1/4 x 8 1/2 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 24.73.1. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924. Source: The Met

James Tissot (French, 1836–1902). Summer, 1876. Oil Paint on Canvas; 91.4 x 50.8 cm (40 x 20 in). London: Tate Britain, N04271. Purchased 1927. Source: Tate Britain

About the Fashion

Tissot’s model wears a white summery afternoon dress made from sheer muslin. The dress is trimmed with lemon-yellow bows, and the skirt has multiple narrow, ruffled flounces. The dress also features a jacketed bodice with a high, ruffled collar, and ruffles trimming the sleeves. She is also wearing a dark colored hat, and holding a parasol and book. Her wedding band reveals her marital status.

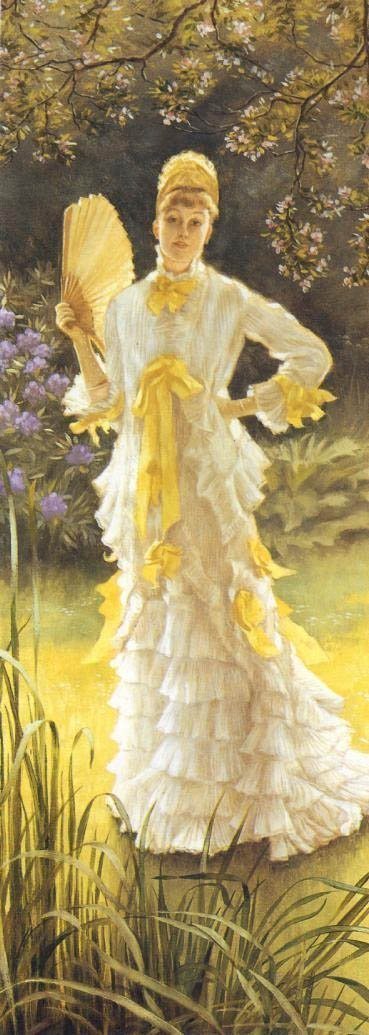

Tissot had a habit of painting the same dress multiple times, and this dress was no different. For instance, Tissot paints this same muslin dress with yellow bows in Spring (Fig. 3) and Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait) (Fig. 4). These two pieces are part of an allegorical series of paintings representing different times of the year. One possible reason for the repetition of this dress was to showcase Tissot’s artistic talent. For instance, in the 2019 James Tissot Exhibition Catalogue, fashion historian Françoise Tétart-Vittu writes of the dress in A Summer Dress with Yellow Ribbons:

“In these works, the delicacy of the semitransparent fabric, the abundance of frills and pleats, and the undone ribbons allowed Tissot to showcase his unique ability to depict challenging details.” (64)

Tissot’s The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (Portsmouth) (Fig. 5), which again features the same muslin dress, also exhibited alongside Summer at the 1877 Grosvenor Gallery.

Fig. 3 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Spring, ca. 1878. Oil on canvas; 60.96 x 24.13 cm (24 x 9.5 in). Private Collection. Source: Stair Sainty

Fig. 4 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait), 1878. Oil on fabric; 112.1 x 85.4 x 6.4 cm (44 1/8 x 33 5/8 x 2 1/2 in). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Bequest of Noah L. Butkin. 1980.288. Source: CMA

Fig. 5 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). The Gallery of HMS Calcutta (Portsmouth), ca. 1876. Oil paint on canvas; 68.6 x 91.8 cm (27 x 36.1 in). London: Tate Britain, N04847. Presented by Samuel Courtauld 1936. Source: Tate Britain

Despite this dress being of contemporary fashion for the time, critics had a lot to say. For example, in August 1877, The Galaxy wrote about the dress (Fig. 5):

“M. Tissot’s pretty woman, with her stylish back and yellow ribbons, will, I am convinced, become less and less charming and interesting as the years or even months go on. Certain I am, at any rate, that I should not be able to live in the same room with her for a week without finding her intolerably wearisome and unrefreshing.” (155)

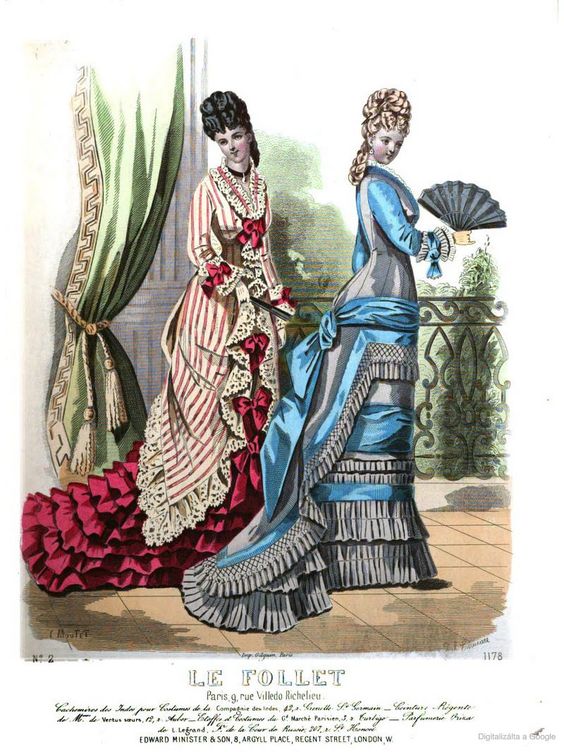

Although Tissot received much criticism on paintings featuring this dress, it was actually a stylish garment of the time. Bows were considered a very popular trimming. Figure 6 depicts a similar white dress with yellow bows from an 1875 La Mode illustrée fashion plate. The bows are placed in similar spots on the bodice and the skirt. The bright yellow color of the bows in both dresses stick out as a contrast from the white fabric. In fact, editor Sarah Hale emphasizes in the September issue of Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine Vol. 93 (1876):

“The fashion of facing bows, cuffs, and headings of flounces with a contrasting color is very popular again.” (294)

Furthermore, 1876 fashion plates from La Mode universelle (Fig. 7) and Revue de la mode (Fig. 8) both feature very similar dresses trimmed with bows of contrasting colors to the main fabric, with the bows placed in similar spots on the neckline, sleeves, down the bodice, and the sides of the skirt.

In addition to bows, ruffles and pleats were also very popular during this time. Figure 9 shows a similar red dress from an 1876 Le Follet fashion plate. In addition to similarly placed brightly-colored bows, the dress also features similar narrow, ruffled flounces towards the bottom of the skirt. These pleated ruffles were very fashionable in addition to the polonaise-style skirt. Fashion editor Jane Thomas writes in the March issue of The London and Paris Ladies’ Magazine of Fashion (1877):

“Polonaises and upper skirts are often cut open at the sides nearly at the hips; the opening wide at the bottom and diminishing to a point at the top: the openings may be laced across with a cord, or be filled with a succession of narrow pleated flounces.” (1)

As it can be seen in Tissot’s Summer, the dress features an upperskirt which splits to reveal narrow pleated flounces. Figure 10 depicts a walking dress with a similar structure. Both dresses have narrow flounces at the bottom of the skirt, ruffled collars, and bows by the sleeves. In addition, both dresses are made out of a light, sheer fabric. Many times, sheer fabric was utilized for morning dresses (Fig. 11); however, sheer fabric was also a popular choice for warm-weathered afternoon dresses because of the airy quality.

Although critics were not always thrilled by the paintings this dress was featured in, there are no doubts that with its brightly colored bows, pleated flounces, and sheer fabric, the dress in Tissot’s Summer, was very fashionable for the time period.

Fig. 6 - Adele-Anaïs Toudouze (French, 1822-1899). La Mode illustrée, 1875. Hand-colored engraving. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. La Mode universelle, 1876. Hand-colored engraving. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown. Revue de la mode, 1876. Hand-colored engraving. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 9 - Artist unknown. Le Follet, 1876. Hand-colored engraving. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 10 - Attributed to House of Worth (French). Walking dress, 1876–82. Cotton, linen. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.6291a, b. Gift of the Princess Viggo in accordance with the wishes of the Misses Hewitt, 1931. Source: The Met

Fig. 11 - Designer unknown (American). Morning dress, 1870–75. Cotton. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.6537a–c. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of Hilda Loines, 1945. Source: The Met

References:

- Anonymous. “Seaside (July: Specimen of a Portrait).” Cleveland Museum of Art, October 30, 2018. http://www.clevelandart.org/art/1980.288.

- Church, William Conant. The Galaxy. W.C. and F.P. Church, 1877. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Galaxy/ukagAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA155&printsec=frontcover

- Hale, Sarah. “Fashions.” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine 93, no. 555 (September 1876): 294 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015034639941&view=1up&seq=284.

- Misfeldt, Willard E. “Tissot, James.” Grove Art Online. 2003; Accessed 5 May 2020. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:3117/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000085236.

- Tétart-Vittu, Françoise. “A Summer Dress with Yellow Ribbons.” In James Tissot. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1127311150

- Thomas, Jane. “Observations of London and Parisian Fashions.” The London and Paris Ladies’ Magazine of Fashion 51, no. 555 (March 1877): 1. https://books.google.com/books?id=WyIGAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA19-IA18#v=onepage&q&f=false