Spring (Jeanne Demarsy) by Édouard Manet is a breathtaking, youthful portrait of French actress Jeanne Demarsy, who exemplifies the title Spring in both her soft facial features and her Parisienne-style outfit. As one of the last paintings done by Manet before his death, Spring symbolizes the merging of female beauty and the beauty of nature, coming together as one to be admired in its totality.

About the Artwork

F

rench painter Édouard Manet is one of the most well-known Impressionists. As a young man, Manet exhibited signs of artistic prowess in his drawings, mainly caricature, but he had high hopes of becoming a naval officer during his young adult years; after failing the entrance exam to the Naval College twice, he pursued a career in the arts instead (The Getty).

Throughout the 1860s, Manet exhibited his works in the Paris Salons, and drew much attention (The Met). Because he did not shy away from bold painting styles or subject matters, he was many-a-time the subject of criticism and harsh rejection from the Salon. By the late 1870s, his health had begun to suffer and as art historian Beatrice Farwell writes, “he spent annual extended curative sojourns in the country near Paris. During these periods, he amused himself by painting small still-lifes and flower-pieces,” like those seen in figures 10 and 11, “and writing letters decorated with charming watercolors” (Grove).

It was around this time that Manet painted Spring (Jeanne Demarsy). In the catalogue accompanying the 1983 Manet retrospective “Manet: 1832-1883,” one of the curators remarked:

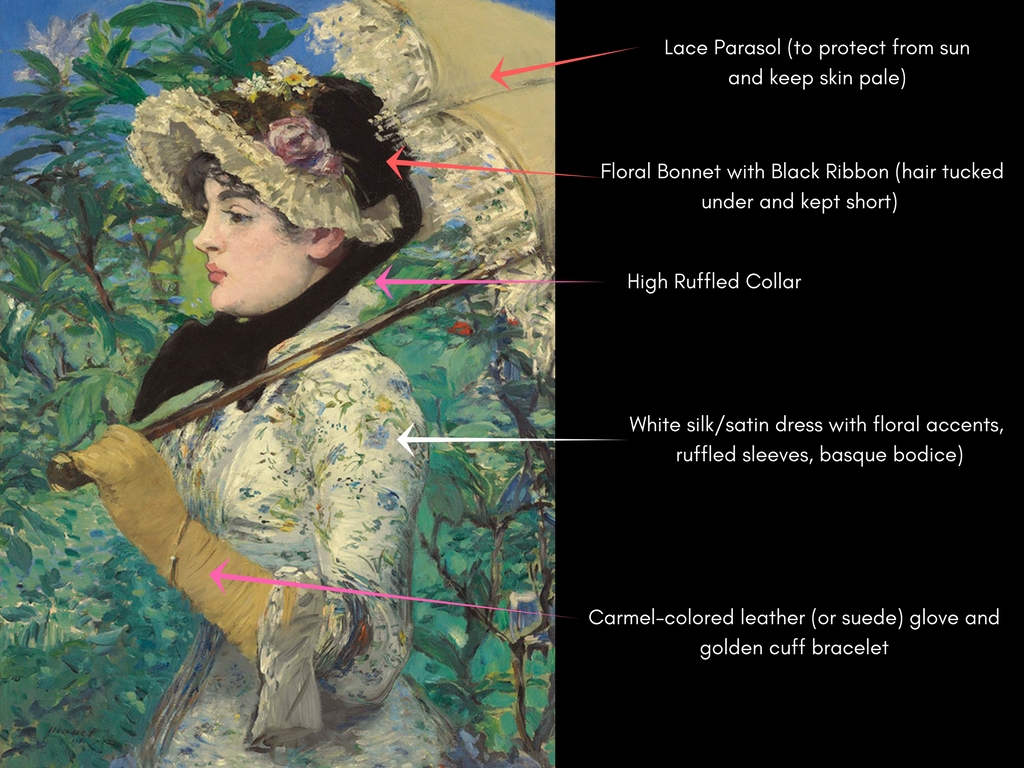

“The portrait of the young actress Jeanne Demarsy, symbolizing Spring, was painted in 1881, probably in response to a commission for four paintings from Antonin Proust (…) Here the image of Jeanne refers to the idea of spring directly, through her flowered dress, her deliciously lacy parasol, the flowers on her bonnet, and the blue sky glimpsed through shimmering foliage.” (487)

This work of art poignantly personifies the Spring season even in Demarsy’s soft, pale skin with hints of rosy hues on her cheeks and lips. The garden in the background, most likely the garden in Manet’s villa, contrasts to her white dress, creating movement in the painting from the umbrella, down to her bonnet that ties around her neck, and then to her hands and down her dress. Her face, at the center of the painting, draws our attention there first, but the parasol’s position behind her head creates a counterclockwise movement that we are somewhat pushed to follow around the painting. She is as poised and prim as a woman of her status – an actress (Figs. 1 & 2) – would be.

Spring (Jeanne Demarsy) is a light, young and airy painting, quite unlike Manet’s darker, more sexually-charged and bold paintings earlier in his career. Perhaps, given his health issues, Manet painted scenes such as those in figures 1, 10 and 11 to reflect on the beauties of life and nature and appreciate them before he died.

Fig. 1 - Chalot of Paris (French). Photograph of Jeanne Demarsy. Photograph. The Library of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Source: 19th Century Photos

Fig. 2 - Atelier Reutlinger (French). De Marsy, ca. 1890. Proof on albumen paper pasted on cardboard; 14.5 x 10.6 cm. Paris: Musée d'Orsay, PHO 1988 28 18. Source: Musée d'Orsay

Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883). Jeanne (Spring), 1881. Oil on canvas; 74 x 51.5 cm (29 1/8 x 20 1/4 in). Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014.62. Source: The Getty

About the Fashion

T

he French actress wears camel-colored gloves, a floral dress with a ruffled bonnet tied around the neck with a black bow, and a light lace parasol. Carol M. Armstrong remarked in Manet Manette that:

“across his career, Manet’s work is marked by its obsession with the complexities of women’s clothing, the feminine fashioning of identity through clothing, and female consumerism.” (293)

And perhaps that’s what we see here, as Jeanne (an actress), wears a head-to-toe floral ensemble, and in essence, represents Spring herself. Figures 6, 7 and 9 reflect the growing interest in florals and spring motifs in fashion, as well as the role they played in women’s fashion. Manet was fascinated with female fashion and in early 1881, before the painting of Spring (Jeanne Demarsy), he had visited establishments of popular milliners for hats and dresses in which to dress Jeanne in (The Getty).

Based on photographs of Demarsy (Figs. 1-2), critics noted that Manet modified the French actress’ features, upturning her nose and slightly enhancing her lips to make her look like the quintessential Parisienne.

In the 2013 “Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity” exhibition catalogue, curator Helen Burnham wrote:

“Manet’s painting of the actress Jeanne Demarsy is less a portrait than an embodiment of fashionable spring. ‘She is not a woman,’ wrote Maurice du Seigneur in his review of the Salon of 1882, where the painting was shown, ‘she is a bouquet, truly a visual perfume’. In contrast to Young Woman in a Round Hat, Jeanne wears an ultrafeminine floral day dress, comparable to period costumes and dresses depicted in fashion plates.” (256)

The dress is fitted, tight around the waist, with loose ruffles around the sleeves that drape down. In the early 1880s, there was a trend of fitted bodices (Fig. 3) that extended to the hips, called a basque, as further seen in figures 4, 6, 8. The dress was most likely made of silk, which was a popular material at this time, and the bodice seems to have been made of a boned, white satin brocade.

Fig. 3 - Martin Decalf Mme (French). Dress, ca. 1882-83. Silk. New York: The MET, 46.88.1. Gift of the Estate of Jane Curtiss Breed, 1946, through James McVickar Breed. Source: The MET

Fig. 4 - Freja. Illustrated Scandinavian Fashion Magazine, 1881. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 5 - Frederick Worth (English, 1825-1895). Afternoon dress (details), ca. 1876. New York: MCNY, 62.190.3A-B. Gift of Richard H. L. Sexton and Eric H. L. Sexton, 1962. Source: MCNY

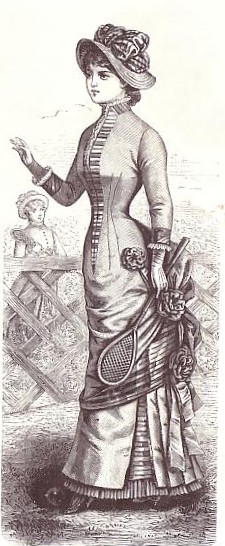

Fig. 6 - S Blum. Victorian fashions and costumes from Harper’s Bazaar, 1881. New York. Source: Cat Whitaker Costume

Fig. 7 - Frederick Worth (English, 1825-1895). Afternoon dress, ca. 1876. New York: MCNY, 62.190.3A-B. Gift of Richard H. L. Sexton and Eric H. L. Sexton, 1962. Source: MCNY

Fig. 8 - Sartoria Giabbani (Italian). Day dress, ca. 1881. Silk satin. Florence: The Palazzo Pitti Costume Gallery, 00000058. Source: Europeana

Fig. 9 - Turner Brand. Dress, ca. 1870s. White kimono fabric. Kyoto: Kyoto Costume Institute, AC8938 93-28-1AB. Source: Kyoto Costume Institute

Fig. 10 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). Young Woman Among The Flowers, ca. 1879. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Source: WikiArt

Fig. 11 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). A Young Woman in the Garden, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Source: WikiArt

Fig. 12 - Édouard Manet (French, 1832-1883). La Promenade, ca. 1880. Oil on canvas; 92.3 x 70.5 cm (36.3 x 27.8 in). Tokyo: Fuji Art Museum. Source: The Athaneaum

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown. L' Art de la Mode, July 1881. Source: FIT Special Collections

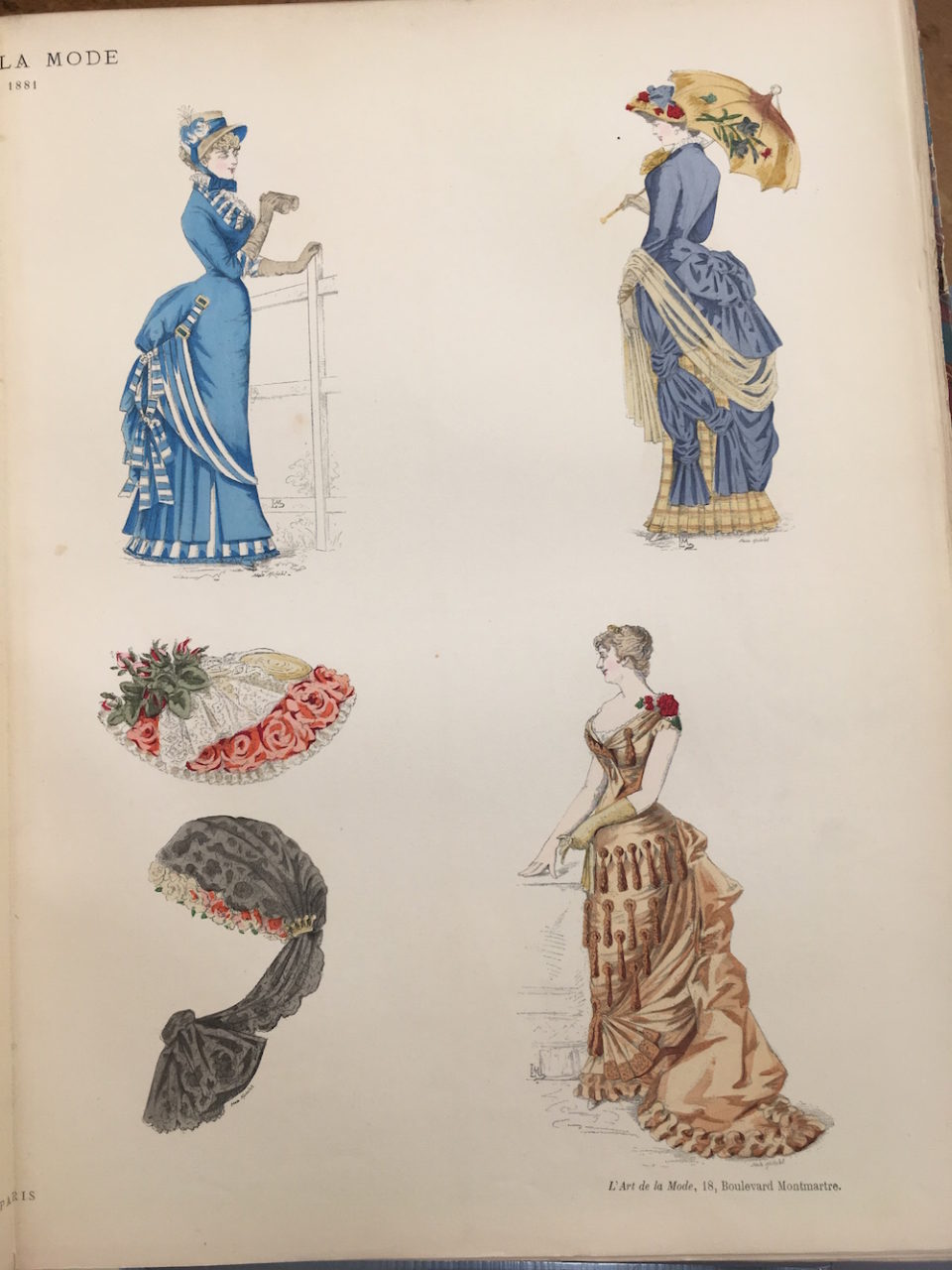

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown. L' Art de la Mode, April 1881. Source: FIT Special Collections

Bonnets similar to Demarsy’s–ruffled and comprised of various flowers–were worn frequently in this time period (see Figs. 7, 8, 10, 11 for examples). The Philadelphia-based journal Godey’s Lady’s Book & Magazine in the 1880 edition under “Chitchat” sub-column “Fashions For June” discussed the appropriate bonnets for women to wear during these times:

“The bonnet to suit this sweet simplicity in coiffure is the Renaissance capote, with border just raised a little at the top, rounded off close above the ear, and with moderately high crown. (…) the trimming is put on very much at the top, and consists of bows and ruches of ribbon, and clusters of leaves and flowers, with occasionally a small bird or tuft of feathers.” (108)

Similarly, in The Ladies’ Self Instructor in Millinery and Mantua Making, Embroidery and Appliqué, Gihon described the materials bonnets were best to be made of:

“Bonnets of this kind, when formed all in one piece, are best made of muslin or of net, and they are especially light and agreeable in the sultry days of summer” (128).

The guide also noted that:

“No doubt, in the choice both of material and of colour, considerable deference must be paid to the prevailing fashion” (125).

The black ribbon that holds the bonnet firmly to Demarsy’s head is fastened around her neck; it’s quite striking given its darkness and contrast to the rest of the light colors in the painting/outfit. It appears to be satin, perhaps even velveteen. Her camel-colored gloves were likely kidskin or suede. Also, dropped waists and high collars were fashionable trends at this time and in the painting, we can see Demarsy has a higher waist than ‘normal’ and a high, ruffled collar camouflaged by the black ribbon. The skirt most likely draped loosely to the floor like that of figure 4, or 7.

The dress is on-trend for this time period with its narrow silhouette, nearly-straight-line skirt, and design details (ruffles, florals). It is quite extravagant for afternoon wear, so it certainly reflects the status of Jeanne as an actress and well-to-do woman; additionally, while parts of it may have been machine-sewn, a majority of appears to have been hand-done and sewn. Appropriate for afternoon teas and walks in the garden, this dress was likely best-suited for an upper-class woman who spent time reading at home or gardening. Jeanne’s outfit in this painting, and more so her pose, are much like that of the woman on the right in the figure 4 fashion plate; both have a parasol to protect themselves from the sun as pale skin was prized at this time as an indicator of a woman’s status and beauty. Similarly, in the fashion plate in figure 14, the top-right image of the women with the floral bonnet and parasol closely resembles that of what we see of Jeanne’s upper body in Spring.

As mentioned earlier, Jeanne’s appearance, particularly her face which Manet did alter slightly, reflects the Parisienne, a stylish, sophisticated beautiful young woman who is more of an object of beauty really than an individual. Like figures 10 and 11, Spring highlights the place of women in gardens and beautiful settings, adding their own beauty to the natural world. In La Promenade (Fig. 12), Manet uses a similar garden setting to set off another Parisienne-like figure, but this time wearing black–an act of sartorial restraint that was also a hallmark of that iconic figure of French fashionability. But, just as Maurice du Seigneur remarked in his review of the Salon of 1882, “she is not a woman”, meaning that she is another lovely sight in this lovely garden, something living that is pretty and can be admired by others.

The golden thin cuff on her left wrist is an interesting small detail that adds to Jeanne’s societal status; the golden cuff, which appears to be open and not fully connected together, is a delicate but elegant addition to this ensemble.

Jeanne appears quite romantic in this painting, given her doll-like facial features and the floral themes (which were vastly incorporated into fashions at this time, as seen in figures 3 and 5) in both her outfit and setting. Floral motifs, fabrics, and designs were often favored at this time, whether in the parasols or bonnets (as seen in figure 14), or in dress such as the one worn in the figure 13 fashion plate. Burnham in Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity commented further on her profile pose:

“A linear convention similar to the profile views in fashion plates, early Renaissance portraiture, and Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, it contributes to Jeanne’s personification as a beauty, a springtime Parisienne.” (256)

Japanese themes were quite vogue in Parisian art and fashions at the time–figure 9 being the most notable of examples. Many artists, such as Berthe Morisot and Claude Monet, were influenced by Japanese art and textiles and incorporated them into their paintings, such as kimonos and Japanese fans.

Its Legacy

Spring (Jeanne Demarsy) was bought by The Getty Museum for $65.1 million at an auction in Fall 2014, clearly showing the significant role of the painting in regards to the Impressionism movement and its place in art history. The brushwork, colors, and Jeanne herself lend to the beauty of the painting that is both captivating and breathtaking.

References

- Allan, Scott. “Édouard Manet’s Spring Now at the Getty Museum.” The Getty Iris (blog), November 25, 2014. http://blogs.getty.edu/iris/this-just-in-edouard-manet-spring/.

- Armstrong, Carol. Manet Manette. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/803776151.

- Cachin, Françoise, Charles S Moffett, and Michel Melot. Manet, 1832-1883: Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, April 22 – August 8, 1983 ; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, September 10 – November 27, 1983. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/718471177.

- “Chitchat, On Fashion For June”. Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine 101 (June 1880): 108. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.57766453;view=1up;seq=94

- Farwell, Beatrice. “Manet, Edouard.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 7 May. 2017. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T053749

- Gihon, J. & J.L. Gihon. The Ladies’ Self Instructor in millinery and mantua making, embroidery and appliqué, canvas-work, knitting, netting, and crochet-work. Philadelphia: Leary & Getz, 1853. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/8608610.

- Groom, Gloria Lynn, ed. Impressionism, Fashion & Modernity. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/794814340.

- “Jeanne (Spring) (Getty Museum).” The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles. Accessed April 9, 2018. http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/268843/edouard-manet-jeanne-spring-french-1881/.

- Rabinow, Rebecca. “Édouard Manet (1832–1883) | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed April 9, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mane/hd_mane.htm.