Lady Meux relied on Whistler’s careful hand and international regard when crafting a new image for herself as an elegant woman who belonged to the elite class into which she had recently married.

About the Portrait

James Abbott McNeill Whistler is an artist most well-known for soft, impressionistic portraits done in muted color schemes. Born in Massachusetts in 1834, Whistler lived most of his life abroad, first going to France in order to refine his artistic skill and eventually settling in London in 1859 (Charles 17). When Lady Meux commissioned Whistler to paint Harmony in Pink and Gray: Portrait of Lady Meux in 1881, he was painting in a post-impressionistic style called ‘tonalism,’ which stood in opposition to the works that his peers were producing. While other popular artists from the time strove to depict the world in its most natural and realistic form, Whistler painted landscapes and portraits in subtle tones and “a harmony of color” (Charles 80).

The figure posing in pink and gray is Lady Meux, known before her marriage as Valerie Susan Langdon. Growing up, Langdon belonged to a family of modest means and was unfamiliar with the extravagant life which the wealthy citizens of London experienced. Langdon worked as a performer until she met and married Sir Henry Bruce Meux. While titled, he was not of the very highest echelon of society; his family owned and managed a successful brewery. Once the flamboyant Langdon found herself in a new social class, however, she felt compelled to transform her public image from an average citizen to an elegant lady, worthy of society. Author Margaret MacDonald comments on this desire to reinvent herself in her book Whistler, Women, & Fashion (2003) when she remarks:

“Marriage to one of the most eligible men in town was but the first of a series of bold, self-transforming steps taken by Meux. Both she and her husband seem to have believed that marriage would convert her into a lady.” (160)

Langdon made various attempts to establish her newfound title, including commissioning Whistler to paint three separate portraits for her depicting her in glamorous and fashionable clothing. The second painting was titled Arrangement in Black No. 5: Portrait of Lady Meux (1881) (Fig. 1); the third portrait was never retained due to a dispute between Langdon and Whistler over the grueling process of sitting for the portrait (The Frick Collection). Each portrait took many sittings and studies (Fig. 2).

After its completion, Pink and Gray was displayed publicly both in the Paris Salon and the Grosvenor Gallery. Whistler’s work was commended for its delicate beauty and grace, and for his ability to show beauty and sensuality in a subject without any vulgarity or eroticism which might offend viewers (MacDonald 174).

Fig. 1 - James Abbott McNeill Whistler (American, 1834-1903). Arrangement in Black No. 5: Portrait of Lady Meux, 1881. Oil on canvas; 194.3 x 130.2 cm (76.5 x 51.25 in). Honolulu: Honolulu Museum of Art, 3490.1. Funds from public solicitation, Memorial Fund, and Robert Allerton Fund, 1967. Source: Honolulu Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - James Abbott McNeill Whistler (American, 1834-1903). Sketch of Lady Meux, 1881. Pen drawing on white laid paper; 17.8 x 11.3 cm (7 x 4.4 in). Connecticut: Davison Art Center, 1937.D1.94. Gift of George W. Davison (B.A. Wesleyan 1892), 1937. Source: Davison Art Center

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Harmony in Pink and Gray: Portrait of Lady Meux, 1881. Oil on canvas; 193.7 x 93 cm (76 1/4 x 36 5/8 in). New York: The Frick Collection, 191.8.132. Henry Clay Frick Bequest. Source: The Frick Collection

About the Fashion

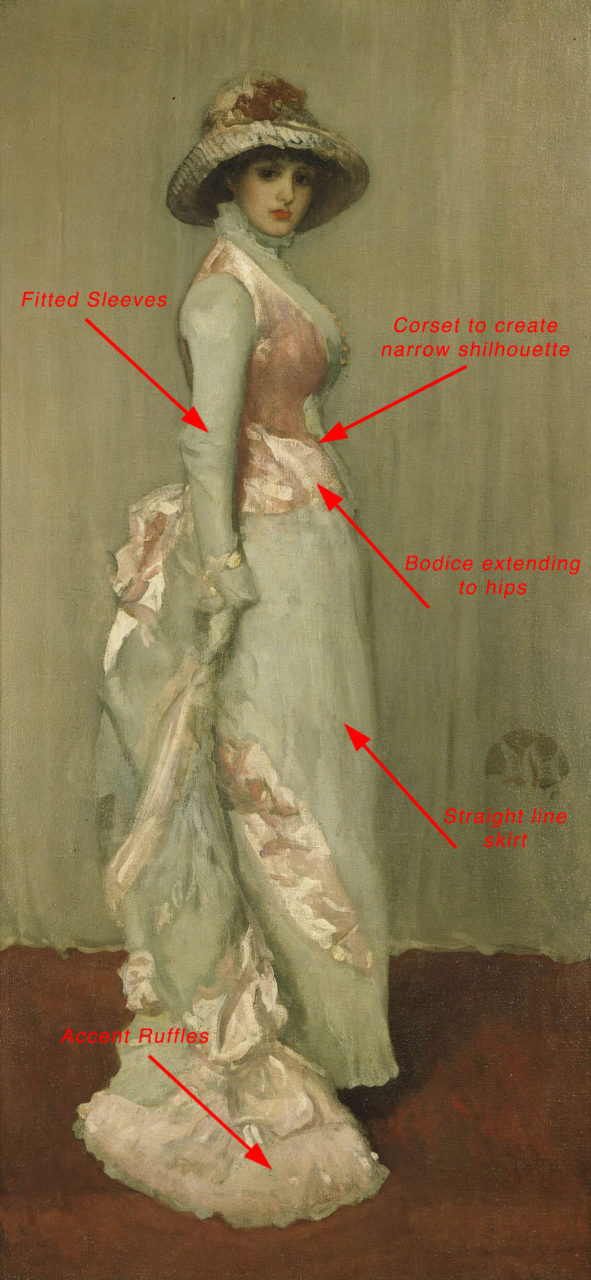

Lady Meux stands in profile with her head turned towards the viewer, allowing for multiple elements of her garment to be seen. The narrow silhouette, or ‘princess line,’ of the dress, which falls into a narrow skirt, stands in contrast to the exaggerated bustles which came before and would follow after. Harper’s Bazar comments on this trend in an 1881 article on “New York Fashions” by stating:

“The skirts are only a trifle over two yards in width, and in many instances have but four breadths in the skirt, as the side gores are now very broad. The fullness is massed at the back by voluminous pleats confined to three or four inches across the back of the belt, while the sides and front gore have darts at the top to do away with all fullness.” (611)

Lady Meux was certainly wearing a corset underneath her dress to create the smooth silhouette, but it is also possible that Whistler took some artistic liberties in order to make her seem as similar as possible to a fashion plate. Her bodice is snugly fitted, and rather than stopping at the waist or creating a seam, it extends to her hips in a common silhouette for this time known as a cuirass bodice (Johnston 62) (Fig. 3). It would blend in smoothly with the rest of the dress due to the blurred painting style except for the color: the pink satin is rendered skillfully to make the bodice catch the light and stand out. The play of light over fabric guides the eye to the back of the dress, where the color descends along the edges of her train.

Chiffon or organdy ruffles adorn the edges of the dress in elegant decoration. These enhancements can be seen around the collar of the bodice, at the end of the long, fitted sleeves, and in an exaggerated manner at the base of the train. Ornamentation like ruffles, drapery, fringe, and beading were a common way to display uncommon elegance and wealth during this time (Fig. 4). The fine touches and attention to detail on Lady Meaux’s dress take it from an plain afternoon garment to an elaborate ensemble worthy of being seen and enjoyed.

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (French). Revue de la Mode: Gazette de la famille, v. 51 plate 124, 1880. Los Angeles: Casey Fashion Plates, Los Angeles Public Library, rbc6194. Source: TESSA

Fig. 4 - Lord & Taylor (American, founded 1826). Dinner dress, 1877-83. Silk and glass. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.34.2a–d. Gift of Elizabeth Kellogg Ammidon, 1979. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 5 - Illman Brothers (engravers) (American, May 1881). American fashions, Summer 1881 (Les Modes Parisiennes and Peterson's Magazine), 1881. Engraving, print, colored; (11.5 x 9.375 in). Claremont, CA: Myrtle Tyrrell Kirby Fashion Plate Collection, Macpherson Collection of the Ella Strong Denison Library, Scripps College, Box 10. Source: CCDL

Although Lady Meux’ fashionable pink and gray gown received no criticism from the public, her hat was subject to ridicule. In Whistler, Women, & Fashion (2003), MacDonald notes that:

“The curious round straw hat with the deep pink ribbon does not appear appropriate to the type of dress the subject is wearing. When the painting was exhibited to generally favorable reviews at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1882 and ten years later at the Salon in Paris, the hat was singled out for derisive comment.” (174)

Critics found the hat to be oversized and bucket-like; fashionable hats in this time were much smaller, or more heavily fitted and curved (Fig. 5).

When Lady Meux commissioned the three portraits from Whistler, she heavily relied on her clothing to convey the message of her new image to the public. Her gowns are not only stylish but also gently elegant, helping her to establish herself as a member of polite society and attempting to erase her history as a poor working girl.

References:

- Charles, Victoria. James McNeill Whistler. New York: Parkstone International, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/758334375

- “Harmony in Pink and Gray: Portrait of Lady Meux.” The Frick Collection. Accessed May 5, 2018. https://collections.frick.org/objects/288/harmony-in-pink-and-gray-portrait-of-lady-meux;jsessionid=3A008D17690FE0DE4989309E04363B1F

- Johnston, Lucy. Nineteenth-Century Fashion in Detail. London: V&A Publications, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/879170559

- MacDonald, Margaret, Susan Grace Galassi, and Aileen Ribeiro. Whistler, Women, & Fashion. New Haven, CT: Frick Collection in association with Yale University, 2003. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50670060

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar Vol. XIV, No. 39 (24 September, 1881). Home Economics Archive: Research, Tradition, History (HEARTH). Accessed May 6, 2018. Link.