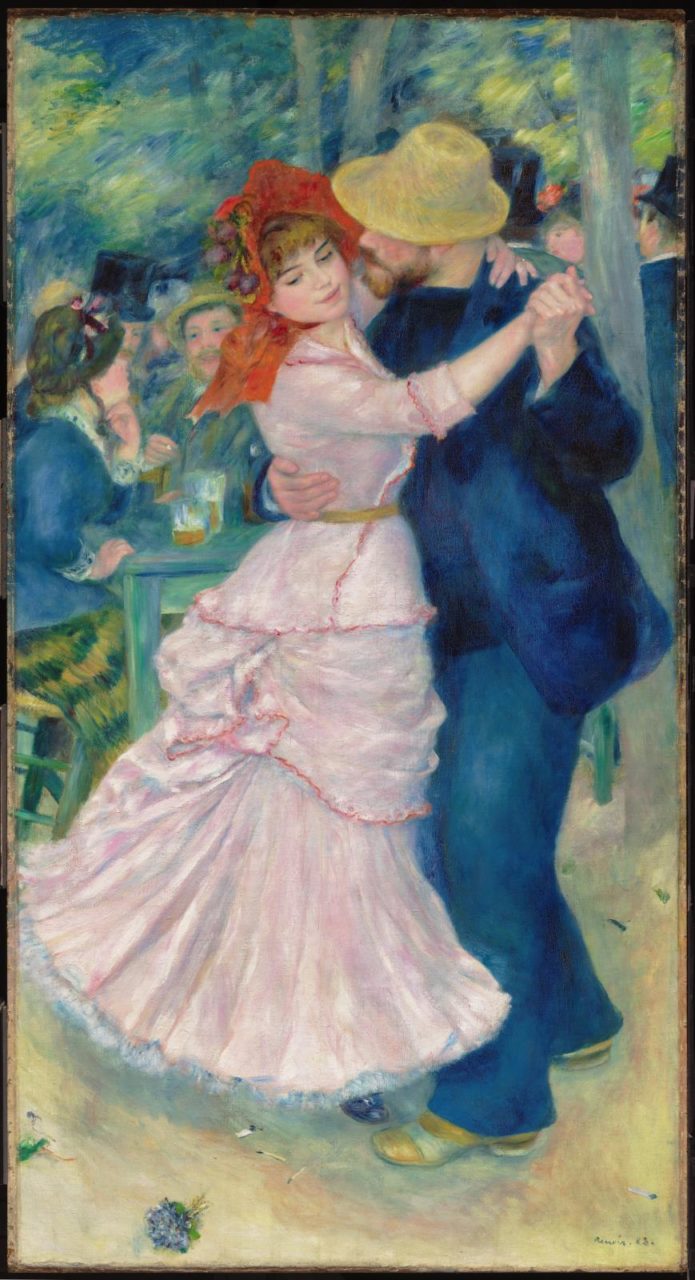

In City Dance, Renoir paints a fashionable Parisienne, waltzing with her dance partner, in a winter ball. Dressed in the latest neoclassically draped evening dress style for young women, the dancer’s simple, draped gown is tasteful and classic in the lack of heavy ornamentation and frills.

About the Artwork

P

ierre Auguste Renoir, son of a tailor, was a leading artist in the Impressionist movement. Born in 1841 in Limoges, France to a family ingrained within the fashion industry, it was expected he would use his artistic talent in illustrating fashion plates. Instead he began to study at the École des Beaux-Arts and to pursue his passion for painting. After repeated criticism and rejection by the Salon jury, Renoir along with other artists founded an independent exhibition society in 1874. However, by the fourth and fifth Impressionist Exhibition, Renoir refused to participate and once again began showing his work in the Paris Salon. This decision cemented a gradual change in his artwork, which shifted from Impressionism to the creations of soft, blurry brushstrokes that have become a defining characteristic of his artwork. City Dance and the linked paintings Country Dance (Fig. 1), and Dance at Bougival (Fig. 2) were painted directly in the period after Renoir’s style began to break away from the traditional Impressionist style, experimenting with a softer, hazier style (Distel).

Renoir hired artist Suzanne Valadon (Fig. 3) to model as the graceful dancer. Her partner whose face is obstructed by his dance partner’s face was Paul Lhote, a close friend of Renoir. Valadon started her modeling career in 1880, with the most famous paintings of her being Dance at Bougival and City Dance (Bailey 168). Valadon remembered how Renoir put much passion and enthusiasm in dressing her for the portrait, going to the dressmakers and milliners to provide au courant fashion, even making sure Valadon’s unusually tiny hands had custom, well-fitting dance gloves on.

City Dance is believed to have been made simultaneously as Country Dance (Fig. 1), and Dance at Bougival (Fig. 2) with all three paintings being started in the winter of 1822, with City Dance and Country Dance finished by March 1883 and Dance in Bougival finished by April 1883. All three paintings were transferred to art dealers for sale eventually. (Bailey 167-168)

Fig. 1 - Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Country Dance, 1883. Oil on canvas; 180 x 90 cm (70.9 x 27.6 in). Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 1978 13. Source: Musée d'Orsay

Fig. 2 - Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Dance at Bougival, 1883. Oil on canvas; 181.9 x 98.1 cm (71 5/8 x 38 5/8 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 37.375. Picture Fund. Source: MFA Boston

Fig. 3 - Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Suzanne Valadon, 1885. Oil on canvas; 41.3 × 31.8 cm (16 1/4 × 12 1/2 in). Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1963.10.60. Source: National Gallery of Art

An exhibition at Durand Ruel’s Grand Salon in March 1883 provided insight into the critical reception of Renoir’s work. Speaking of City Dance, Henry Morel wrote:

“The second group represents an elegant Parisienne, accustomed to the chandeliers of a salon, who leans against her well-behaved cavalier. She shows us her adorable socialite’s profile, her matte shoulders, her well-modeled arm, and the graceful nape of her neck. The very serious young man looks at her as they turn together- they really do turn- at the movement of a waltz and the voluptuous thoughts that it inspires in both of them make their faces turn even more pale. I believe that few painters are capable of painting side by two almost identical compositions, one interpreted in the open air, the other in the artificial light of an apartment.” (quoted in Bailey 186).

Morel believed that Renoir captured an enigmatic beauty of the two dancers, and that, most certainly, the woman dancing epitomized a Parisienne. Despite the exhibition being a success, and the positive acclaim, the paintings remained unsold, and were returned to Renoir. In 1886, the paintings were sent once again on exhibition in Belgium, with one critic stating that the paintings were:

“such a licentious array of garish reds, greens, and blues.” (quoted in Bailey 186).

Renoir faced serious criticism in Belgium, as the critic had a poor opinion about almost every aspect of his painting. However, by 1892 Georges Lecomte in his book studying Impressionism featured all three paintings with a positive outlook. (Bailey 186)

Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). City Dance (Danse á la ville), 1883. Oil on canvas; 180 x 90 cm (70.9 x 27.6 in). Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RF 1978 13. Source: Musée d’Orsay

About the Fashion

C

ity Dance illustrates a graceful, languid couple. This portrait takes place in a marble dancing hall that is decorated in the background with palm trees and other fronds and some flowers. This would have been an evening ball in the city for dancing. The setting would have been white-tie formal, with women in full, extravagant evening gowns especially made for dining and dancing, and men in dress coats with long tails. The color and style of the woman’s dress indicated that the ball would have been a White Ball, made for younger women, who wore less elaborate and stylized dresses called robes legéres, suitable for a young woman transitioning from her teens. The white fabric of the dress would have indicated that the ball took place in the winter, as had been the style for some years now (Bailey 170).

The woman in the portrait is wearing a white silk satin evening dress in the robes legères style, for young women, draped in a classical style. The dress has a fashionable heart-back neckline, referring to the v-neck. The neckline and straps of the gown are trimmed with frothy ruffled organza trim that is translucent. The bodice of the dress continues a couple of inches below natural waistline, transitioning into the skirt. The skirt of the dress is draped in asymmetrical layers of pick-ups of draping that is hand-tacked in place. The hem of the skirt is trimmed with self-ruffle trim.

The woman is wearing a sprig of flowers in her hair, either fabric flowers arranged on a comb, or a arrangement of fresh flowers, picked with the purpose to add scent and natural beauty to the wearer. She also wears long dancing gloves, presumably made of either kidskin or satin, that extend to her elbow. Peeking out just under the frothy ruffles of her skirt are delicate white satin dancing shoes, that appear to be ornamented with matching ruffle trimming.

This ball dress featured in the painting would have been most likely be custom made, commissioned from a dressmaker. It is possible the woman would have brought a fashion plate, or would have chosen one in the dressmaker’s shop to base a stylish dress after. After that, custom trimming, draping, and shaping could have been customized to meet the customer’s taste and to flatter her figure best. It is very possible that seams could have been sewn by machine, but depending on the affluence of the shop or dressmaker, they may or may not have used one.

The ideal body of the time would have been inspired by the classical silhouette found in Greek and Roman statuary. Women should be tall and lithe, with a gently rounded hourglass silhouette, and tiny waist. An elongated silhouette was preferred. The woman in City Dance features a very realistic version of the ideal body, probably less exaggerated because of her youth. Renoir’s Portrait of Madame Clapisson (Fig. 4) features a similar bodice and silhouette with rounded shoulders and bust, with a nipped in waist, and full flouncing skirts. The neckline appears the same, even trimmed with the same transparent, cut fabric. Her hair is even arranged in the same manner.

Fig. 4 - Pierre Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919). Madame Léon Clapisson, 1883. Oil on canvas; 81.2 x 65.3 cm (32 x 25 ¾ in). Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1933.1174. Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection. Source: Art Institute

Fig. 5 - Morris & Co. (British). Evening suit, ca. 1885. Wool barathea, lined with satin and linen, faced with ribbed silk. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.171 to B-1960. Given by B. W. Owram. Source: V&A

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown. Journal des demoiselles, pl. 1 (January 1, 1883). New York: Special Collections & College Archives, Fashion Institute of Technology. Source: Author

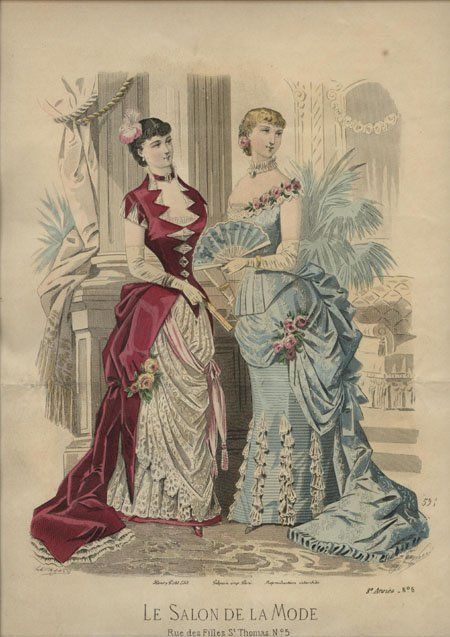

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. Le Salon de la Mode, 1883. Source: Pinterest

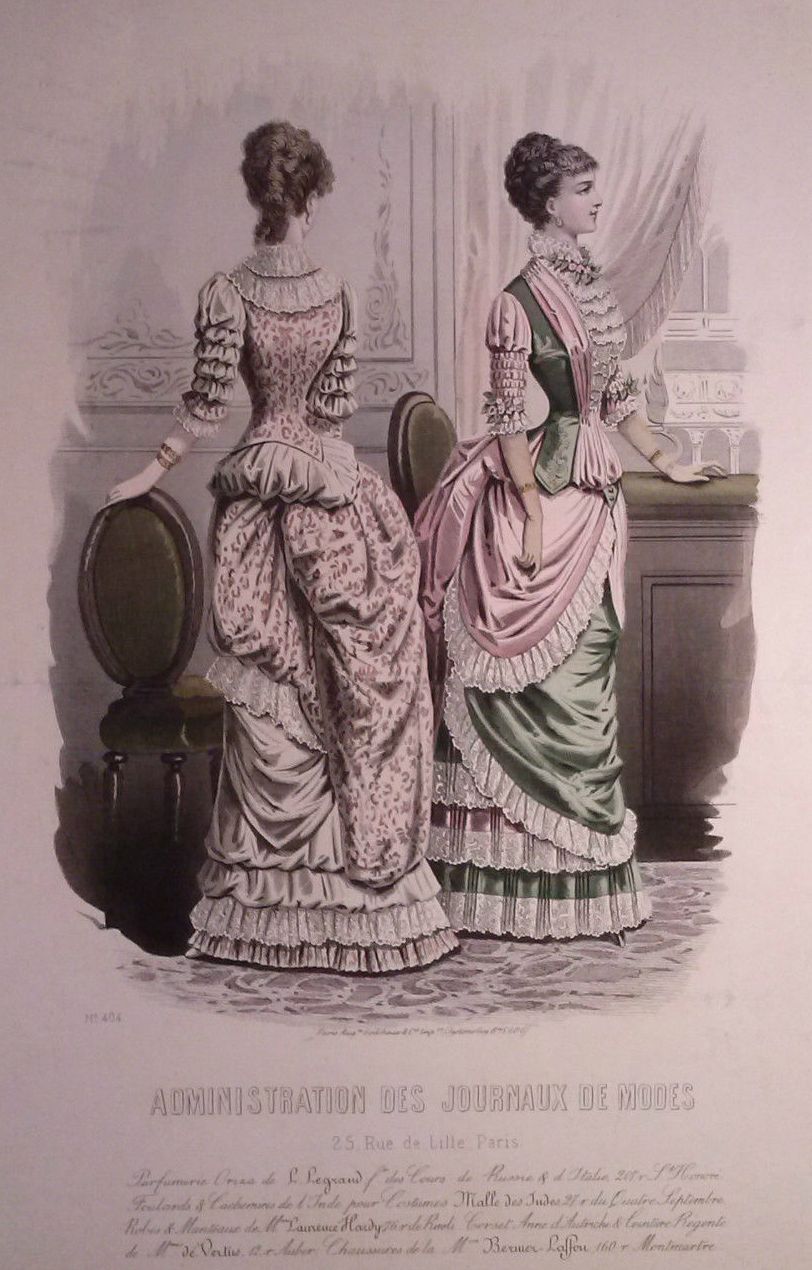

Fig. 8 - Artist unknown. Administration des Journaux de Modes, 1883. Source: Pinterest

The man’s dress coat is most likely made out of a fine black worsted wool. White cuffs peek out from the jacket, indicating he is wearing a fine, starched cotton shirt, that closes at the cuff with gold cuff links. Presumably he would also be wearing a white waistcoat and cravat. He too wears white gloves. His suit could have been bought ready-made and then tailored to fit or custom made from a tailor. The shirts and cravat would have been most likely ready-made and not tailor-made. The Victoria & Albert Museum has a similar suit in its collection from ca. 1885 (Fig. 5).

City Dance contrasts greatly with both Country Dance (Fig. 1) and Dance at Bougival (Fig. 2) through fashion location, and the personalities of the people depicted. Out of the three paintings, City Dance features the most stoic expressions and the most formal locations and fashion. Both Country Dance and Dance at Bougival feature women and men dressed in simple day clothes, filled with vivacity and energy, that the formalities and customs of the city repress. The gleaming smiles and sweeping movement of both country dances contrast sharply with the rigid formality that the ball in the city expresses.

The Journal des demoiselles was a fashion magazine specifically for young ladies and one of its fashion plates from January (Fig. 6) ties in perfectly with the fashion from City Dance, with both dresses depicted as appropriate for a winter ball. The necklines, draped folding, and cascading trains all correlate with the fashion from City Dance, emphasizing how fashionable this look was for young ladies.

Godey’s Lady Book from 1883 confirms the fashionability of white evening dresses with draping for young ladies stating:

An “evening dress for young lady made of cream color albatross […] with drapery” was fashionable for evening wear. (464)

Figure 7 is also very similar to the young woman’s dress, showing more advanced ornamentation. The necklines are very similar and illustrate the trend of more bateau necklines in the front, with deeper V-necklines in the back. The draping in figure 7 carries into the train in a similar way as in City Dance. An 1883 fashion plate (Fig. 8) shows more of the classically inspired draping pick-ups that would be done around the bustle area.

The otherwise plain and unadorned evening dress, made in the style for young ladies, is fashionable and tastefully reflects the youthful beauty of the dancer. Figure 9 shows a similar dress, also in cream, but the fabric flowers and bows makes the dress more ornamented than the dress from City Dance. However it does indicate a very similar ruffle under the draping presumably in place for decoration, but also as an guard against dirt.

The young woman in City Dance is very fashionable, but in the way dictated by her age. The classical draping, clean lines, and lack of gaudy ornamentation, allows her youthful glow to shine in the artwork, and does not compete with her. The white color of the dress, appropriate for a winter ball, also adds to her beauty and fashionably, drawing on her youth. Although her evening dress would be considered conservative, the tasteful choice allows her to wear the dress, not the other way around.

Fig. 9 - House of Worth (French, 1858–1956). Evening dress, ca. 1882. Silk and fabric flowers. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.635a, b. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection. Source: The Met

Its Legacy

R

enoir enthusiasts continue to appreciate City Dance, as seen in Andrea Chung and Mauricio Ardila’s photographic recreation of the painting at the Frick’s 2012 Belle Époque Ball (Fig. 11). This event was part of the Frick’s exhibit “Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting,” which ran from February 7 through May 13, 2012 and featured City Dance, Country Dance, and Dance in Bougival, among other selected works.

Fig. 11 - Photographer unknown. Andrea Chung and Mauricio Ardila re-enact Renoir's dancing couple, 2012. Source: New York Social Diary Blog

References:

- “Auguste Renoir Danse á la ville en 1883.” Musée d’Orsay. Accessed May 6, 2017. http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/index-of-works/notice.html?no_cache=1&nnumid=1160.

- Bailey, Colin B. Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting. New York: Yale University Press, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/786139582.

- Distel, Anne. “Renoir, Auguste.” Oxford Art Online. Accessed May 6, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T071492.

- “Fashions.” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine 106, no. 635 (May 1883). https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=umn.31951d00322067g;view=1up;seq=438

- “Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting” The Frick Collection. Accessed May 6, 2017. http://www.frick.org/sites/default/files/archivedsite/exhibitions/renoir/checklist.htm.

- Rosenberg, Karen. “Soigné Parisians, Fit for a Grand Canvas.” New York Times. Accessed May 6, 2017. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/10/arts/design/renoirs-full-length-paintings-at-the-frick-collection.html