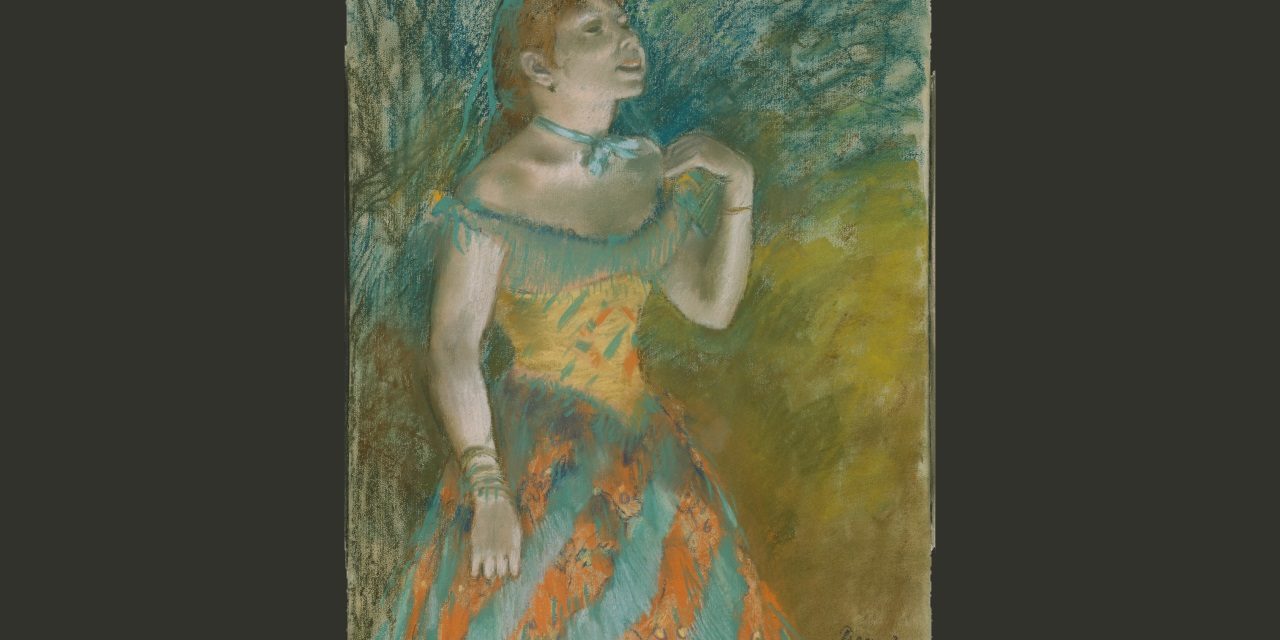

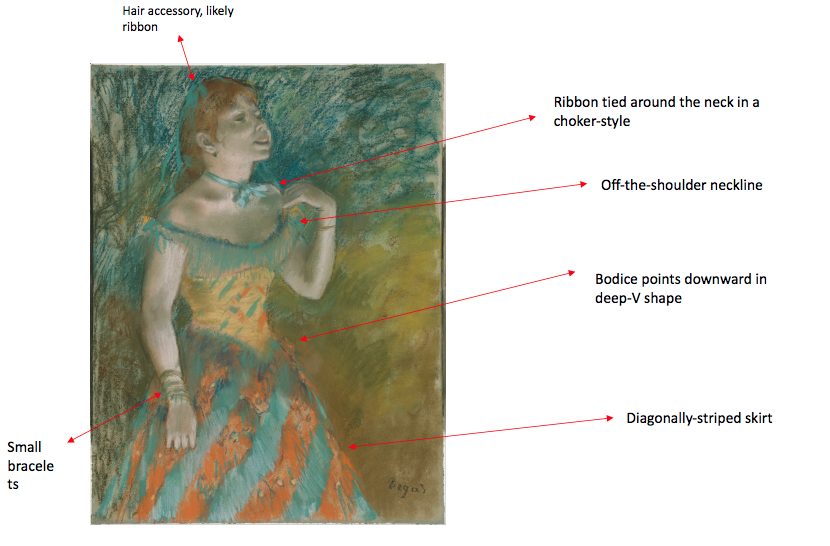

Although dressed in theatrical costume, Degas’ Singer in Green contains details that were fashionable for women’s evening wear at the time, including an off-the-shoulder neckline, a downward-pointing bodice, a diagonal-striped pattern, and a choker-style necklace. What is less fashionable is its lack of applied florals and the bold color palette, which signals the fact that it is a costume.

About the Artwork

This 1884 pastel The Singer in Green was created by reluctant Impressionist Edgar Degas. Born in 1834 into a wealthy family who supported his interest in painting, the French Degas studied in Rome the classical style of the 15th and 16th centuries and began painting academic subjects. It was this training that influenced his use of unique framing in his work as he would often cut a portion of his subject out of the picture (Monnier). Degas then transitioned his subject matter to depicting scenes of urban life, then more specifically café singers, actresses, and ballet dancers. Despite being a founding member of the Impressionist group, a collection of artists who came together to organize exhibitions to combat the Salon, Degas shunned that title, preferring to be thought of as a realist. Indeed, Degas never depicted plein-air landscapes unlike his fellow Impressionist painters; he preferred the artificial light of cafés, theaters, cabarets, etc. (Schenkel). Degas lead the Realist subgroup among the Impressionists (Monnier). He preferred to depict life as it was happening before his eyes, and in the 1978 monograph Degas, the realist is described as:

“A master of tension, the intense atmosphere of the room: he makes the room’s very emptiness ring.” (67)

Later critics appeared to be in consensus about Degas’ uncanny ability to capture movement, with author François Fosca stating in his 1959 monograph:

“Degas’ men and women are almost always moving about, or resting a moment after some exertion.” (85)

The young woman in this artwork certainly appears to have been caught between belting notes for an invisible audience. Degas created The Singer in Green just shy of a transitory time in his artistic career as he began painting an extensive series of nudes in 1885 (Monnier). Prior to this, though, his subject matter mostly depicted ballet dancers, actresses, and singers. It is unsurprising that the medium is pastel, for even though Degas began as an oil painter, he began mixing in the medium of pastels before using that as the sole medium for his works by the 1880s (Healy 82). In Degas (1965), Jean Bouret explains the reason for this change, stating:

“Degas had used pastel as a means of saving time because he felt he needed to turn out a great deal of work and wanted to get money from Durand-Ruel to pay off the family bankruptcy; but his conscience drove him to do more and more work on whatever picture he had on hand. He derived little or no advantage from the final result.” (117)

It was merely a matter of convenience for Degas; it was something that he felt he had to do to help his family recover from financial troubles. Medium plays an important role in this particular piece, though, for Ruth Schenkel writes in “Edgar Degas: Painting and Drawing” that:

“The Singer in Green demonstrates Degas’s use of pastel to achieve the effect of the glare of footlights illuminating his subject from below and his use of coarse hatching to suggest the curtained backdrop behind the singer.”

Little is known about the young singer depicted in the piece, although many attest that it is Marie von Goethem, the same model that Degas used for his sculpture, The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer, seen in figure 2 (Met). One may only assume that she was a young, working-class theater or café singer, likely in her teens. Similarly, figures 3-4 are other works by Degas that depict female performers mid-song. The exhibition history for The Singer in Green is extensive, the pastel first being exhibited in 1899 and over a dozen times since until most recently in 2007 (Met). The reception at the time was mixed, and Degas knew this. He understood that his subject matter of urban low-life was not for everyone, but those who saw this as true realism were impressed (Monnier).

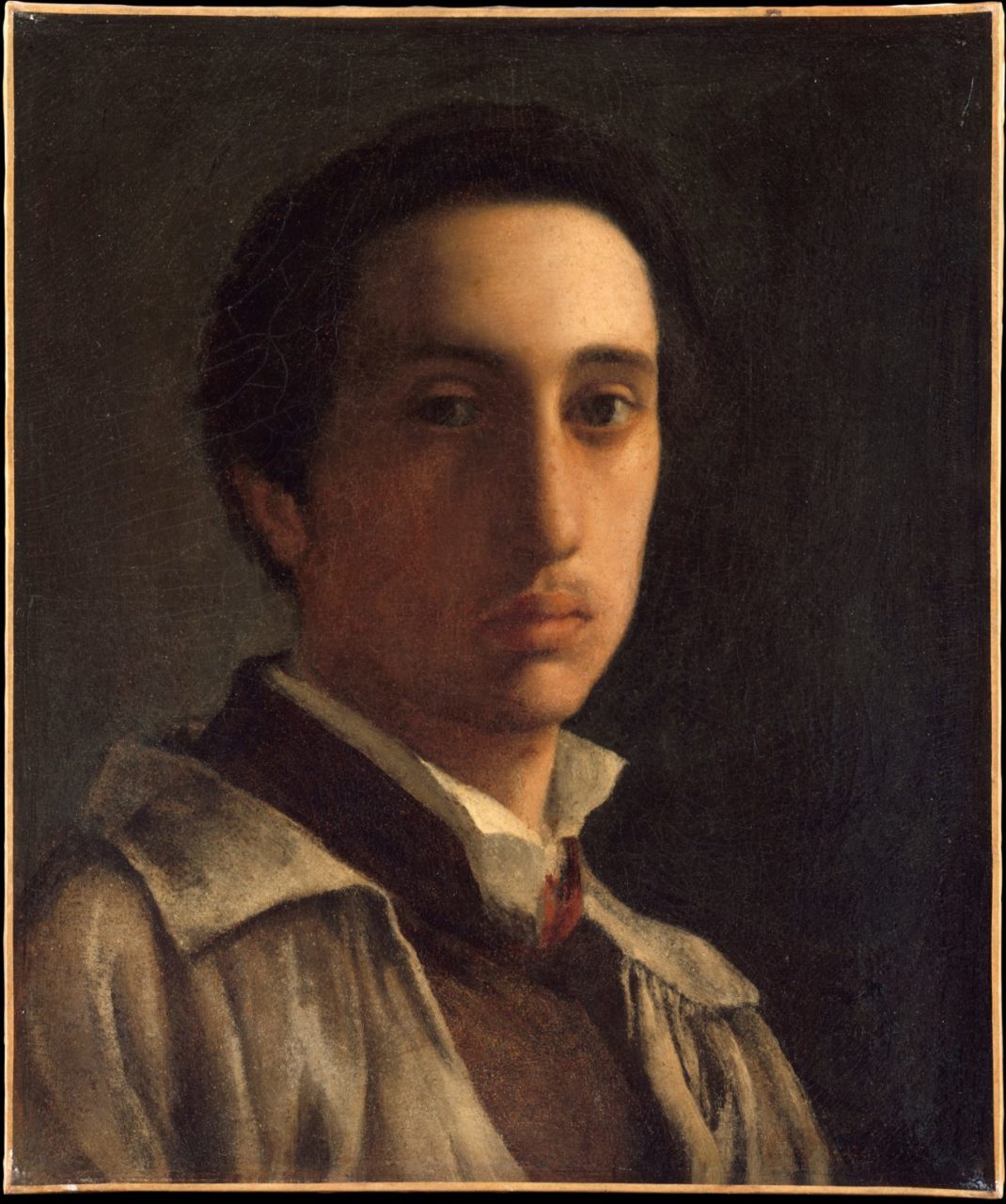

Fig. 1 - Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). Self-Portrait, 1855-56. Oil on paper, laid down on canvas; 40.6 x 34.3 cm (16 x 13 1/2 in). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 61.101.6. Bequest of Stephen C. Clark, 1960. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 2 - Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer, 1878-1881. Pigmented beeswax, clay, metal armature, rope, paintbrushes, human hair, silk and linen ribbon, cotton faille bodice, cotton and silk tutu, linen slippers, on wooden base; 98.9 x 34.7 x 35.2 cm (38 15/16 x 13 11/16 x 13 7/8 in). Washington, D.C.: Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1999.80.28. Source: National Gallery of Art

Fig. 3 - Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). The Cafe Concert (The Song of the Dog), 1875-1877. Gouache, pastel; 51.8 x 42.6 cm. Private Collection. Source: WikiArt

Fig. 4 - Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). Singer with a Glove, 1878. Pastel on canvas; 53.2 x 41 cm (20 15/16 x 16 1/8 in). Cambridge: Harvard Art Museums, 1951.68. Bequest from the Collection of Maurice Wertheim, Class of 1906. Source: Harvard Art Museums

Edgar Degas (French, 1834-1917). The Singer in Green, 1884. Pastel on light blue laid paper; 60.3 x 46.4 cm (23 3/4 x 18 1/4 in). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 61.101.7. Bequest of Stephen C. Clark, 1960. Source: The Met

About the Fashion

The dress that the singer is wearing while performing is short-sleeved and off-the-shoulder; the corseted part of the bodice is yellow with turquoise and orange detailing, while the top is solid turquoise. The bottom of the bodice points downward into a V-shape, separating it from the diagonally-striped orange and turquoise skirt. Although Degas’ style makes it hard to decipher the details of the dress, one could assume it was likely made out of silk or taffeta given that it is a costume rather than a day dress. The dress is complimented by various accessories: bracelets on each arm, dainty earrings, what appears to be turquoise ribbons in her hair, and, most notably, a silk turquoise ribbon tied tightly around her neck in a choker-style.

Because this dress is a costume intended to be worn by a singer while she is performing on stage, it mimics the structure and silhouette of evening wear during this time as opposed to more casual day dresses. The bold colors reflect the fact that it is a costume and is therefore a bit more theatrical than the standard evening dress. Because it was worn by a working-class woman, and singers were not highly regarded in society, this dress was likely relatively inexpensive and perhaps even homemade as sewing patterns and department stores made fashionable styles accessible at many price points.

The 1887 photograph in figure 5 depicts British actress Lillie Langtry in a gown with a similar neckline to that seen in The Singer in Green. The almost fringe-like texture at the top of the bodice along the neckline on Lillie’s dress reflects what is seen on Degas’ singer; the end of Lille’s bodice also points downward in a V-shape. Figure 6 depicts a woman photographed in theatrical costume two years before Degas’ work, wearing a similar off-the-shoulder neckline and pointed bodice.

Fig. 5 - Sarony (American). Lillie Langtry, 1887. Photograph. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 6 - W&D Downey Photographers (British). Guy Little Theatrical Photograph, 1882. Sepia photograph on paper. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, S.142:370-2007. Bequeathed by Guy Little. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 7 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Mrs. Wilton Phipps, 1884. Oil on canvas; 88.9 x 64.8 cm. Private collection. Source: WikiArt

Fig. 8 - Alfred Stevens (Belgian, 1823-1906). Baroness de Bonhome, 1886. Pastel; 195.6 x 82.6 cm. Private collection. Source: WikiArt

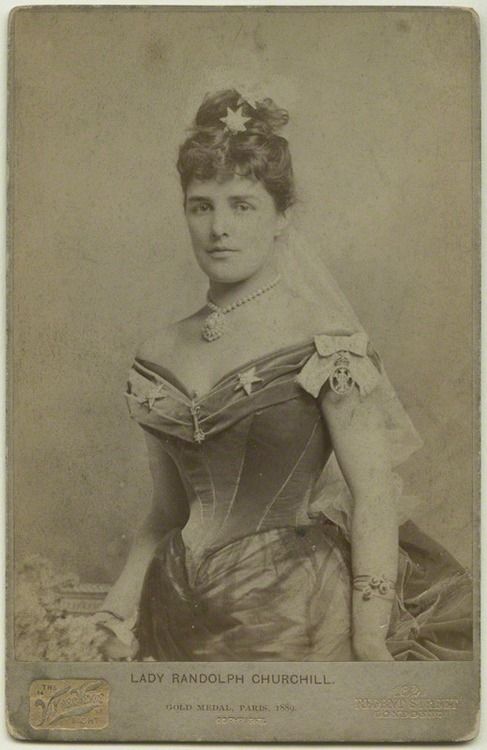

Fig. 9 - Henry Van der Weyde Albumen. Jeanette, Lady Randolph Churchill, 1887. Photograph. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 10 - Photographer unknown. Kronprinzessin Stéphanie Wedding Photo, 1881. Photograph. Private Collection. Source: Grand Ladies

A portrait by John Singer Sargent from the same year as The Singer in Green (Fig. 7) shows similar details to Degas’ singer. In both, the choker necklace and small bracelets are used for accessorizing, stripes are used as a pattern, and yet again the bodice points sharply downward in a V-shape. Painted two years after Degas’ singer, figure 8 depicts a wealthier adaptation of a similar silhouette to the dress that the singer is wearing, this gown being accentuated by more lavish accessories such as gloves and a headpiece. The woman is still wearing a silk ribbon around her neck, though, and a similarly-shaped bodice.

Floral corsages or bouquets appear frequently in these comparison images; however, not a single flower is depicted on Degas’ singer, which is strange as it appeared to be a major trend both on gowns and accessories in the 1880s. There is some suggestion of a small floral pattern on the skirt, however. Trends seen in Singer in Green spanned the decade, as seen in figures 9 and 10. Figure 9, a photograph from 1887, shows Winston Churchill’s mother in an off-the-shoulder gown detailed with ribbon and wearing a choker necklace. All of these same features can also be found in a wedding photograph from 1881 in figure 10. Both women are wearing accessories in their put-up hair.

Fig. 11 - Artist unknown (French). Société des Journaux de Modes Rénuis, 1884. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown. Lady Dunlo, 1880s. Photograph. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 13 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode Illustree, 1884. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

A fashion plate from 1884 shows that the trends in evening wear at this time were tight-fitting necklaces, pointed-bodices, and off-the-shoulder sleeves (Fig. 11). The use of diagonal stripes as a pattern was prevalent during this time as well, the photograph in figure 12 depicting a woman in a striped gown that shifts from diagonal on the bodice to vertical on the skirt. Figure 13 is taken from La Mode illustrée in 1884, and again one can see the use of diagonal stripes. The “New York Fashions” article of an October 1884 issue of Harper’s Bazar explains:

“In such a dress the wide stripes should also be diagonal across the front and sides of the skirt, but the back breadths should be pleated to conceal the red under the blue stripes.” (675).

In addition, the author also had this to say of bodices:

“Another fancy is that of putting a velvet point or V-shaped plastron in the diagonal front, and not trimming it otherwise.” (675)

It is evident that, although the costume depicted in Degas’ The Singer in Green consists of a bold color palette that distinguishes it as a costume rather than a typical gown, the silhouette, structural details, and accessories reflect the trends in women’s fashion of the time period.

References:

- Bouret, Jean. Degas. Translated by Daphne Woodward. London: Thames and Hudson, 1965. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1327069.

- “Edgar Degas | The Singer in Green.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed May 6, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/436159.

- Fosca, François. Degas. Geneva: Skira, 1959. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/10516318.

- Hüttinger, Eduard. Degas. Translated by Ellen Healy. New York: Crown Publishers, 1978. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/733266663.

- Monnier, Geneviève. “Degas, (Hilaire Germain) Edgar.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Accessed May 7, 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000021805.

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar 17, no. 43 (October 25, 1884): 675. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/harpersbazaar/docview/1850159606/fulltext/370FFE56F8DB4584PQ/14?accountid=27253

- Schenkel, Ruth. “Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Painting and Drawing.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Accessed May 7, 2018. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dgsp/hd_dgsp.htm.