Faustina appears to be the ideal woman of 1899 as her dress includes all of the most fashionable evening wear details, like short puffed sleeves, lace details, and a curvaceous silhouette. She embodies beauty and grace as the artist captures her during a private moment of reflection in her extravagant home.

About the Portrait

A

ccording to the Museo Nacional del Prado, Manuel Domínguez Sánchez, a Madrid-born artist, was trained as a painter and illustrator at the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. He then proceeded to submit works to the National Exhibitions of Fine Arts, winning an award in 1871 for his most famous painting, The Death of Seneca. A realist at the start, Sánchez’s oeuvre is mainly based on myths and historical events, but he was also commissioned for many individual and collective portraits by wealthy patrons, such as Faustina Peñalver y Fauste, marquesa de Amboage, which he painted at the age of 54. According to the Prado, Faustina was the daughter of a Magistrate of the Spanish Supreme Court, and she became the second wife of the Marques de Amboage, Ramón Pla Monge. A very wealthy man, Monge commissioned a variety of works by well-known Spanish artists for his castle, including the bust of Faustina pictured in figure 1. This life-size portrait of his wife was most likely meant to be displayed in their palace, which is now the Italian Embassy building in Madrid.

In the painting, Faustina is positioned in the center, seemingly in motion as she turns to look out to a point the viewer cannot see. Perhaps she is posing so as to appear to be in a ballroom or a living room, where she has stepped off to the side for a moment. Her fan is in motion and the train of her dress is wrapped around her, as if she had turned and was beginning to walk in a different direction. It is unclear if she is in her home, but this conclusion is likely correct because she appears very comfortable in her opulent surroundings, as she has discarded her gloves and has laid her cloak or wrap haphazardly on the chair to her left. While the painter portrays the marquesa as if he had captured her during a private moment, it is very apparent that she is posing, as exemplified through her perfectly orchestrated background and dress, fanned out on her side to show off its lavish luster. Though the subject is not in a casual garment or setting, the painter attempts to convey a portrait of feigned intimacy, as the wealthy woman poses in her sumptuous environment, seemingly taking a brief minute to herself in a presumed social setting that is obscured from the viewer. Through her carefully arranged gown and surroundings, Faustina achieves the goal held by all fashionable women in the 19th century, as explained by Aileen Ribeiro in Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity:

“The aim of a woman of fashion, as expressed in etiquette books, was to ‘bring her toilette into harmony . . . with her character, mood, age, face, complexion, and the color of her eyes.’” (197)

Fig. 1 - Mariano Benlliure Gil (Spanish, 1862-1947). Faustina Peñalver y Fauste, dowager Marchioness of Amboage, 1914. Carrara marble; 73 x 60 x 42 cm (28.7 x 23.6 x 16.5 in). Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, E000800. Legacy of Faustina Peñalver y Fauste, dowager Marchioness of Amboage, 1916. Source: Museo Nacional del Prado

Manuel Domínguez Sánchez (Spanish, 1840-1906). Faustina Peñalver y Fauste, marquesa de Amboage, 1899. Oil on canvas; 241 x 131 cm (94.8 x 55.6 in). Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, POO4284. Source: Prado

About the Fashion

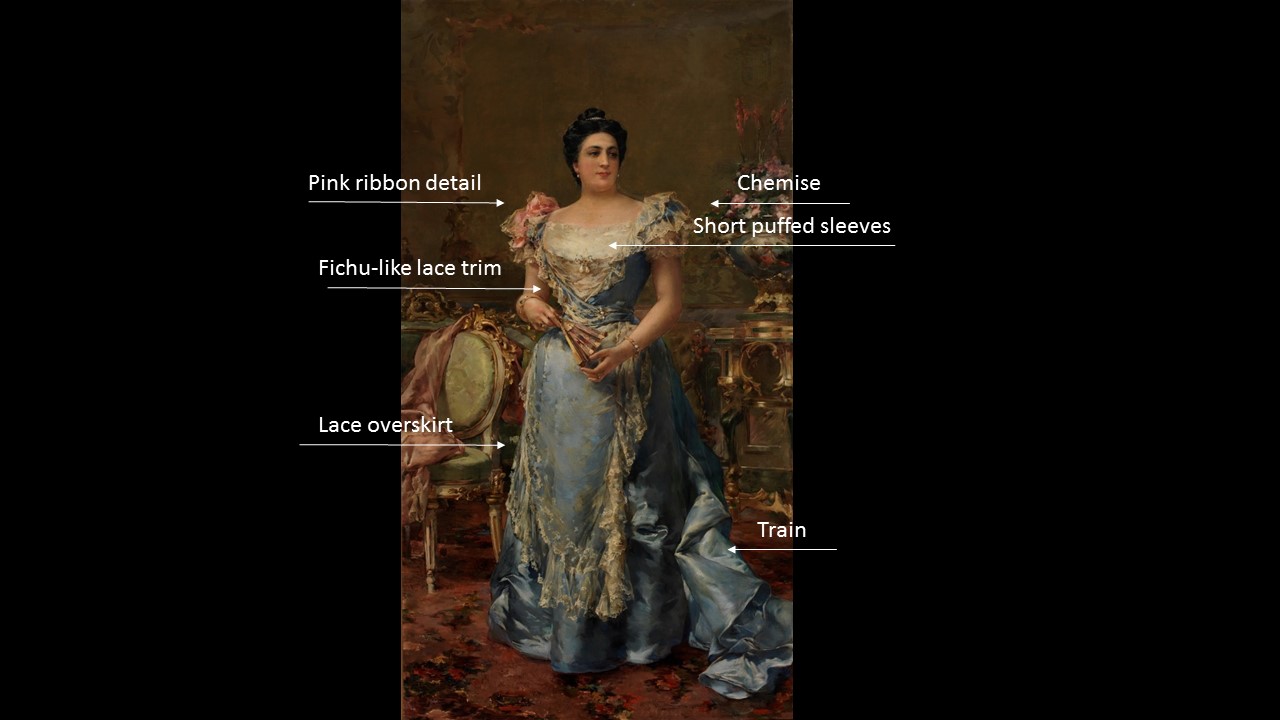

In the portrait, Faustina wears an evening or dinner gown appropriate for any formal event in 1899. Her dress appears to be comprised of an expensive pale blue satin or silk, adorned with frothy lace on the bodice, sleeves, and overskirt. The dramatic décolleté V-neck of her gown endangers the wearer of losing her modesty; however, Faustina has allowed her silky, ivory chemise to peep out from her gown, covering any inappropriate amount of skin that could potentially be on display. The painting in figure 2 displays a German duchess wearing a similar gown that is cut in a cleavage-bearing fashion, but she allows her chemisette to cover the bosom, much like Faustina. The V-neck of Faustina’s dress is bordered by a decorative trim of translucent, ruffled lace, traveling across her bust to form the apex of the V at her waist in an asymmetrical point. The addition of lace to her décolleté neckline creates an almost fichu-like effect, giving the gown an elegantly modest appearance while still drawing attention across her bust to her minuscule waist. The dress in the upper left hand corner of figure 3 exhibits a nearly identical use of trimming, an extremely tasteful detail for evening gowns in 1899. Harper’s Bazar writes:

“The fancy for lace trimming has proved more than a passing one… a band of guipure passes over the shoulder and descends into a V shape to the center of the back and front… The beauty of guipure is best enhanced by combining it with light, delicate evening tints of silk.” (417)

In like manner, her neckline fulfills both fashionable styles for evening gowns in 1899, as it is square cut with the illusion of being a V-neck. Harper’s Bazar touches on this trend, declaring that:

“The fichu effects become more and more fashionable all the time… they are shaped so as to give the right breadth to the shoulders without making the figure too square… they are a great addition to evening gowns. Evening gowns are to be cut in two ways… quite off the shoulders or else square necks. V shape is fashionable only in the trimming.” (758)

Figure 4 serves as an example of a fichu effect, very similar to that used in Faustina’s gown, and both garments feature sleeves comprised of puffed layers of lace. The sleeves of her gown are short and puffed, almost balloon-like, and they are covered with tiered layers of lace descending down her fashionably pale and supple arms.

Fig. 2 - Philip de László (Hungarian, 1869-1937). Ratibor, Duchess of, née Countess Maria Breunner-Enkevoith, 1899. Oil on canvas. Philip de Laszlo Archive Trust. Source: Philip de Laszlo Archive Trust

Fig. 3 - Artist unknown (French). Les Elegances de la Semaine, 1899. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17520939. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown (American). Full dress Toilettes, March 1898. Private Collection. Source: Vintage Victorian Fashion History Library

Fig. 5 - Jean-Philippe Worth (French, 1856–1926). Ball gown, 1898. Silk, rhinestones, and metal. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1324a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Fig. 6 - Sir Edward John Poynter (English, 1836-1919). The Hon. Violet Monckton, 1899. Oil on canvas; 213.8 x 152.6 cm (84.17 x 60 in). Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 6078. Anonymous gift arranged by the artist 1913-14. Source: Art Gallery NSW

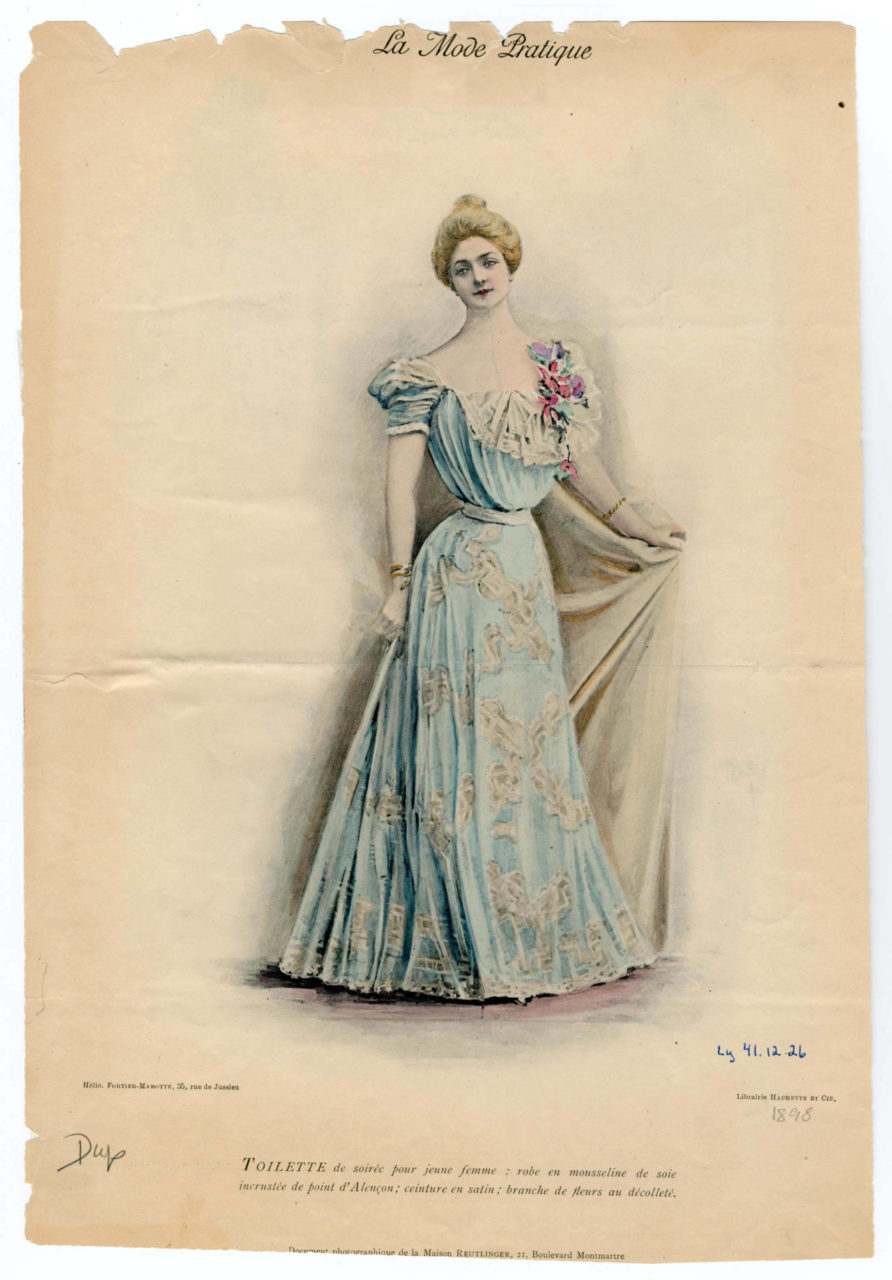

Fig. 7 - Designer unknown (French). La Mode Pratique, 1898. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, b17520939. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The gown features an interesting pink ribbon detail on the cap of her left sleeve only, adding diagonal interest from the trimming at the waist, which is concluded on her right side. The artificial broadness of the shoulders, created by the layers of lace, further emphasizes her wasp waist, the defining characteristic of the late 1890s silhouette. In like manner, the 1898 gown from the House of Worth shown in figure 5 displays a great deal of puffed lace and ruffles around the shoulders and bust, drawing attention to the breadth of the wearer’s upper body while creating the illusion of an even smaller midriff. Similarly, the theatrical balloon sleeves shown in figure 6 accentuate the subject’s waist in contrast, further exhibiting the effect used by women to sculpt their bodies with gown silhouettes in addition to corsets. Moore’s The Woman in Fashion further details this unrealistic body shape, explaining that:

“Ladies laced up the corset so tightly that it created a new figure distortion… The new fashionable ideal was therefore achieved: a full, forward bosom, a tiny waist, and generous backward-slanting hips.” (128)

Faustina’s ample hips make her waist seem smaller as well, and she wears a lovely apron-like overskirt of lace, which serves to lengthen her figure as well as to provide additional adornment. The fashion plate from 1899 in figure 7 shows off a lace overskirt as well; however, it spans the entire width of the skirt, not just the front section. In regards to silhouette, the subject’s gown is quite fashionable in that the skirt of the garment falls straight in the front but seems to have some fullness in the back. The Pictorial Review from 1899 elaborates on the desired shape for evening gowns, writing:

“This is the time of year when the tailor-made gown occupies the center of the stage… the skirts cling to the knees. They are straight in front, flare a trifle at the sides, and spread into a wide flare in the back. They are very long all around and trail from two to four inches… They give that sinuous wriggle to the hips that is characteristic to the Spanish women…” (7)

Her fashionably long train is showcased in the portrait as well, as it is brought around to the front as if Faustina had been in the process of turning when the artist captured this moment. As for jewelry, she wears stylish emerald and pearl bracelets and rings, which are her only accessories besides her pearl earrings and hair circlet. Though not the main focus of her outfit, Faustina still maintains a perfectly fashionable appearance in her taste of decoration, as in an 1899 article, “Modish Jewels,” Vogue advised women that:

“The queen jewel of the moment is the emerald… Pearls reign triumphant year after year, being found in greater beauty and size than was thought possible when their modishness was slumbering… foreign women are never seen without them, night or day.” (x)

Overall, Faustina herself seems to be the ideal of beauty in 1899, as women were more focused on silhouette as opposed to specific trimmings and details. Thus, one can conclude that Faustina is perfectly fashionable, as she fulfills the requirements for a fashionable gown in the late 1890s, as detailed in The Survey of Historic Costume:

“Although vestiges of the bustle remained in pleats or gathers concentrated at the back of the skirt, the silhouette of the 1890s could be described as hourglass shaped. By mid-decade, sleeve styles were large and wide at the top for both day and evening. Waists were as small as corsets could make them, and skirts flared out into a bell-like shape.” (Tortora 337)

References:

- “Domínguez Sánchez, Manuel.” Museo Nacional del Prado, May 3, 2018. https://www.museodelprado.es/aprende/enciclopedia/voz/dominguez-sanchez-manuel/112973e3-a8cd-4533-a027-ec250d94725c.

- “Faustina Peñalver y Fauste, marquesa de Amboage.” Museo Nacional del Prado. Accessed May 3, 2018. https://www.museodelprado.es/coleccion/obra-de-arte/faustina-pealver-y-fauste-marquesa-de-amboage/e0589fa5-478b-43ca-b1ea-b6f824d90330.

- “Modish Jewels.” Vogue 14, no. 21 (November 23, 1899): x.

- Moore, Doris. The Woman in Fashion. New York: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1949. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/631779491.

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar 32, no. 36 (1899): 758.

- “New York Fashions.” Harper’s Bazar 32, no. 20 (1899): 417.

- Ribeiro, Aileen. Impressionism, Fashion, and Modernity. Edited by Gloria Groom. Chicago: The Art Insitute of Chicago, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/843185621.

- Tortora, Phyllis G., and Keith Eubank. Survey of Historic Costume: A History of Western Dress. 5th ed. New York: Fairchild Publications, 2010. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/865480300.