About the Portrait

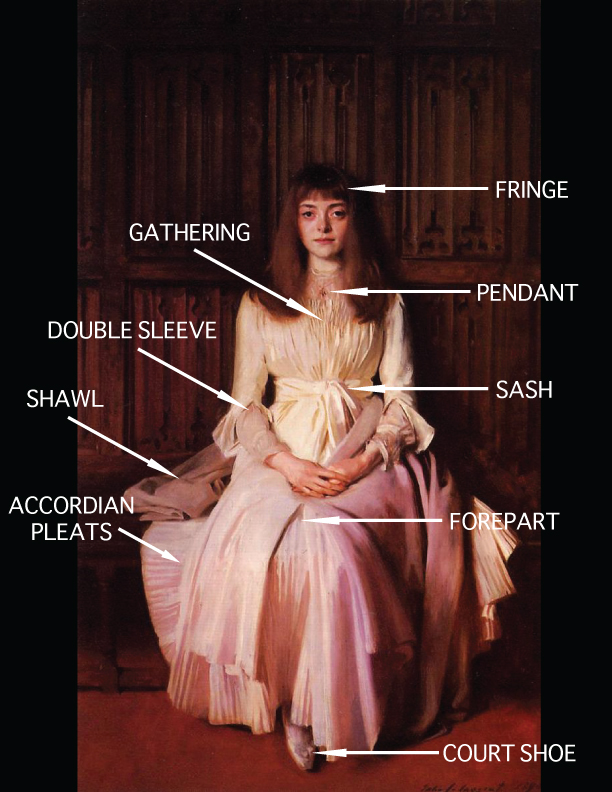

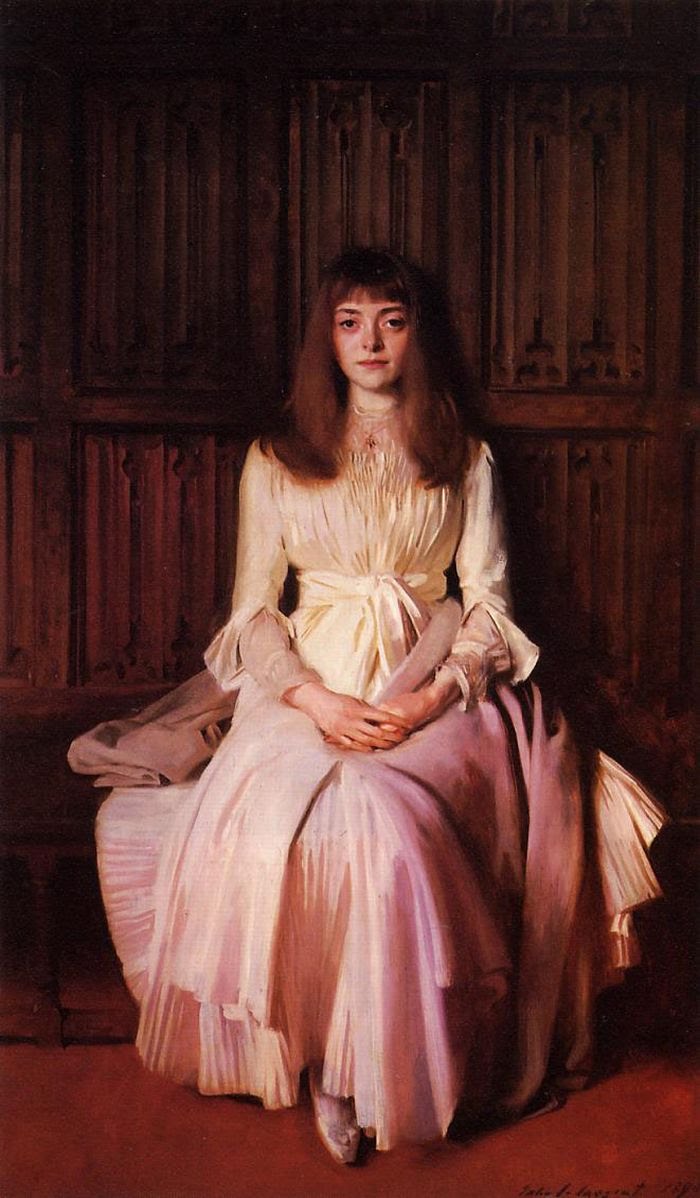

Fifteen years into his career, Sargent was commissioned to join the elite Palmer family at Ightham Mote, a grand manor outside of Kent, to paint their youngest daughter Elsie (fig.1). Elsie’s father was an American general and founder of Colorado Springs, thus the family found themselves in a position of great fortune (The Royal Oak Foundation). As a result, the family commissioned many portraits of their daughter (fig. 2), some of which are still held in the family’s private collection. However, in preparation for the more than life sized portrait Miss Elsie Palmer, also known as Young Lady in White, or Girl in White, Sargent did a number of studies (fig. 3) and sketches (fig. 4) of the seventeen year old girl. The enormous oil portrait now resides at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center where her haunting stare has guests dubing her the “Mona Lisa of Colorado Springs” (Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center).

Though it was a commissioned portrait, Miss Elsie Palmer was one of only three paintings Sargent exhibited in 1891. It was met with relatively successful reviews, as critics were intrigued by the sitter’s piercing gaze. Many tried to find a portrait to compare to the pose and dress of the young woman, but were rather unsuccessful due to the unique nature of the artwork and the clothes which she posed in (Gallati 124-126).

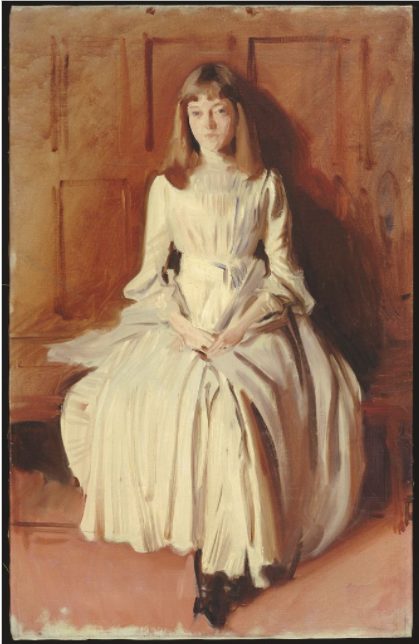

Fig. 1 - Henry Vander Weyde (Dutch, 1838-1924). Elsie Palmer, 1889. Photograph. Colorado Springs: Special Collections, Tutt Library, Colorado College. Source: Author

Fig. 2 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Elsie Palmer, 1889-1890. Oil on board; 60.5 x 32.5 cm (23.8 x 12.8 in). Private Collection. Source: Pubhist

Fig. 3 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Study for "Elsie Palmer", 1889-1890. Oil on canvas; 76.2 x 49.2 cm (30 x 19.4 in). Cambridge: Harvard's Fogg Museum, 1942.58. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Grenville L. Winthrop, Class of 1886. Source: Harvard Art Museums

Fig. 4 - John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Elsie Palmer, 1890. Brown ink on off-white wove paper; 26.4 x 35.5 cm (10.4 x 14 in). Cambridge: Harvard's Fogg Museum, 1937.7.27.2.B. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond. Source: Harvard Art Museums

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856-1925). Miss Elsie Palmer, 1889-1890. Oil on canvas; 190.8 x 114.6 cm (75.1 x 45.1 in). Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center. Image: artrenewal.org

About the Fashion

Seventeen years old at the time the portrait was painted, Elsie’s wardrobe and the fashionabilty of it fall into somewhat of a grey area. Not quite a woman, yet not quite a child, Sargent portrays Elsie trapped on the edge of adolescence. Her hair is worn down with short blunt fringe, or bangs, in a style that was only acceptable for children at the time, yet her tea gown is long and full, a silhouette that would have been much too drowning for a child. On this very juxtaposition, Barbara Dayer Gallati writes in Great Expectations: John Singer Sargent Painting Children:

“Elsie’s sibylline countenance corresponds with the mysterious emotional and physical transformations that were associated with [adolescence]. The idea of adolescence achieved remarkable force in cultural and scientific arenas about 1890, when studies (both literary and scientific) focused on the years bridging childhood and adulthood and offered interpretation of it not only as a physical awakening of sexuality but also as an evolutionary stage” (126).

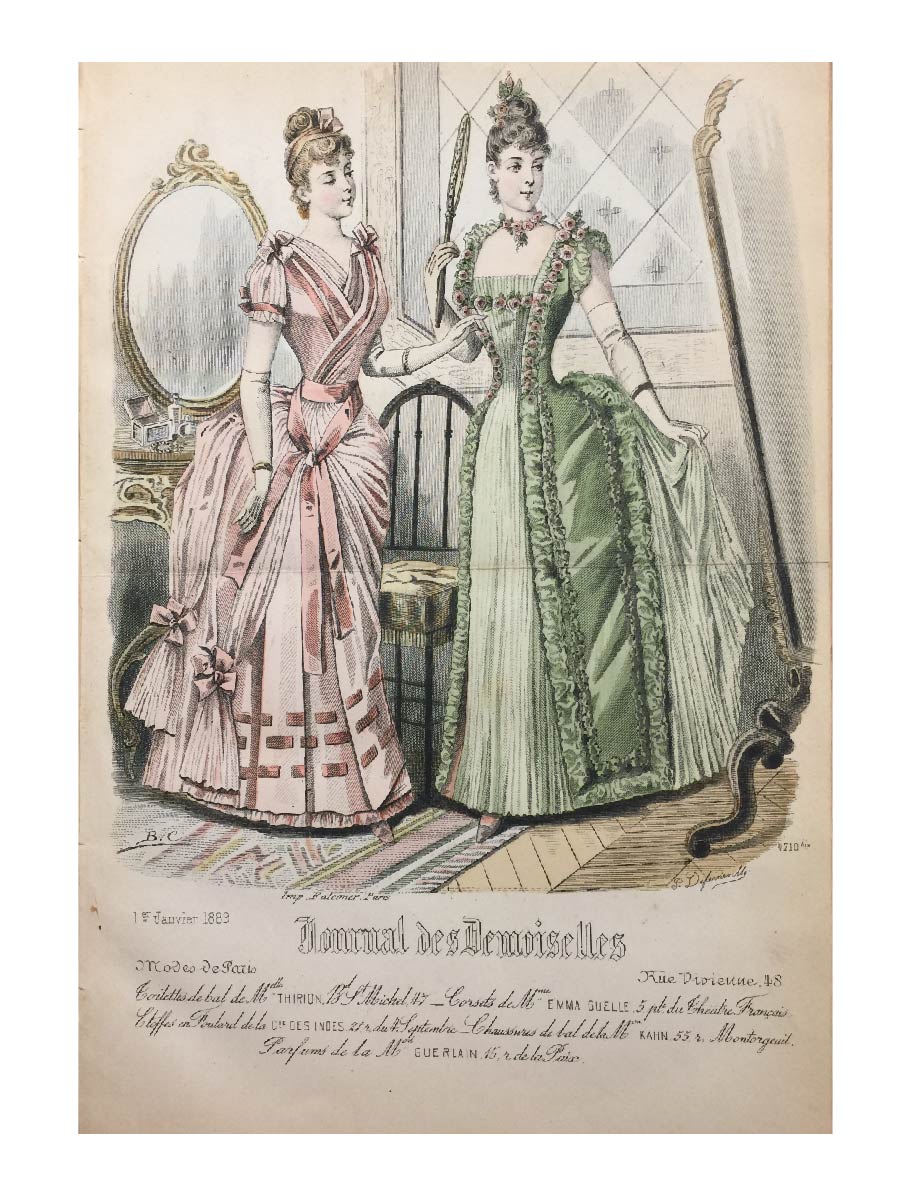

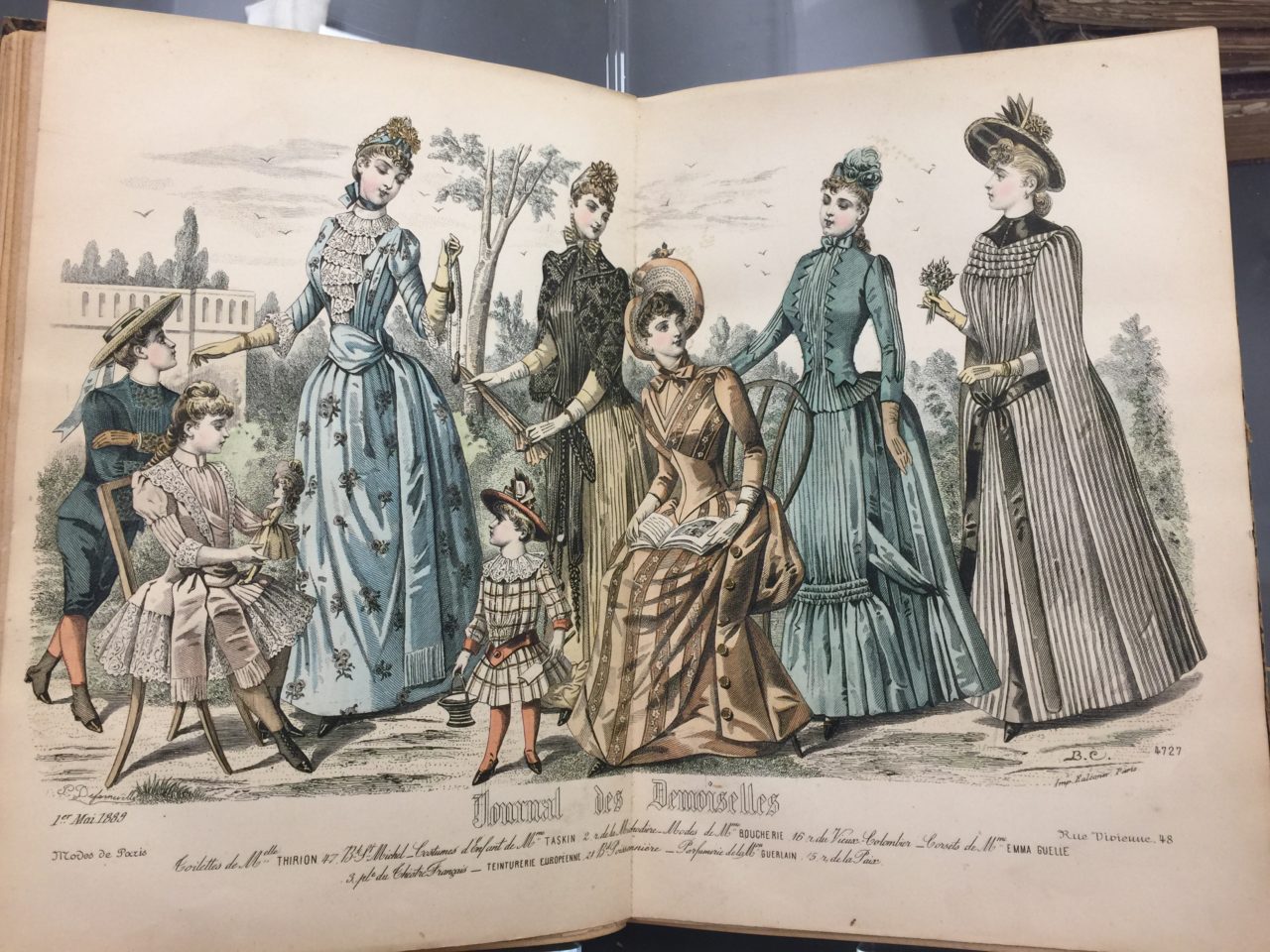

With this in mind, the style of Elsie’s clothing must be assessed with both women’s wear and children’s wear trends in mind. During the late 1880s and early 1890s the most fashionable women’s silhouette was one of volume and excess. One of the biggest fashions was the bustle, which consisted of some sort of structure underneath the skirt to provide volume at the rear. Most fashion plates and fashion press (fig. 5) represented the concept of “more is more,” i.e. more volume, bows, sashes, rosettes, frills, pleats and lace (Calahan). While Elsie’s dress may have some of these details, like the satin sash and pleated skirt, her costume certainly does not live up to the fullness and grandeur that was published in fashion journals of the time. In children’s wear, however, less fitted, more playful silhouettes were popular. Perhaps the fashion plate of 1890 that Elsie’s dress is most similar too is that of a child’s dress, complete with high neck, satin sash, gathered bodice, and loose pleated skirt (fig. 6). However, Elsie’s costume presents itself with much more length and maturity than the outfit of a little girl.

Thus, without conforming entirely to one set of style guidelines, Elsie finds herself on the outs of mainstream fashion and one must look to trends that were not yet being advertised in major publications. Aesthetic dress was one of these outcast trends that was rejected by the mainstream fashion movement and fashion press for decades. In Fashion Plates: 150 Years of Style, April Calahan describes the trend:

“In terms of clothing, the members of the Aesthetic movement were proponents of dress reform and advocates for “artistic dress,” which, for women, was characterized by a relaxation of the corset, the lack of a bustle, and a looser, draped fit that was often inspired by historical attire” (274).

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown (French). Journal des Demoiselles, January 1, 1889. New York: Special Collections, Library at The Fashion Institute of Technology. Source: Author

Fig. 6 - Artist unknown (French). Journal des Demoiselles, May 1, 1889. New York: Special Collections, Library at The Fashion Institute of Technology. Source: Author

Fig. 7 - James Jebusa Shannon (Irish, 1862-1923). Violet, Duchess of Rutland, 1889. Oil on canvas. Leicestershire: Belvoir Castle. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 8 - Liberty & Co. (British, 1875-). Tea gown, ca. 1885. Silk. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 9 - Liberty & Co. (British, 1875-). Dress, 1891. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.68.53.9. Gift of Mrs. James G. Flockhart, 1968. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“The Rational Dress Society protests against the introduction of any fashion in dress that either deforms the figure, impedes the movements of the body, or in any way tends to injure the health. It protests against the wearing of tightly-fitting corsets, of high-heeled or narrow-toed boots and shoes: of heavily weighted skirts, as rendering healthy exercise almost impossible; and of all tie down cloaks or other garments impeding the movement of the arms. It protests against crinolines or crinolettes of any kind as ugly and deforming.” (1)

Surviving garments of the aesthetic dress movement of the 19th century highlight the simpler and less restricted silhouette that mirrors the dress of the figure in Miss Elsie Palmer. With waists that are cinched by satin sashes rather than restrictive corsets, these dresses (fig. 8-9) demonstrate that while Elsie’s costume may not have aligned with the mainstream trends of her day, Sargent still painted a fashionable look (though it may have only been fashionable in the eyes of like-minded liberal women).

With her long straight locks of hair that fell to her shoulders like a child and her white satin dress that rejected the standards of mainstream fashion, Elsie finds herself on the border of two raging battles: woman or child and mainstream fashion or dress reform. Nonetheless, Sargent’s Miss Elsie Palmer is an enthralling painting full of dichotomy and fashion history.

Its Legacy

References:

- Calahan, April. Fashion Plates: 150 Years of Style. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015.

- “Coveted Singer Sargent Painting Returns Home.” The Royal Oak Foundation, Nov. 28, 2016, accessed May 1, 2017.

- Gallati, Barbara Dayer. Great Expectations: John Singer Sargent Painting Children. Brooklyn, NY: Bullfinch Press, 2004.

- “January Members.” Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center, January 2017, accessed May 1, 2017.

- Ormond, Richard. “Sargent, John Singer.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed May 1, 2017, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T076043 (subscription required).

- “The Rational Dress Society’s Gazette.” The Rational Dress Society no. 4 (December 1888-January 1989).