Emulating the work of Old Masters, William Merritt Chase paints Lydia Field Emmet wearing black as a fashionable color and immediately catches the viewer’s attention with the shocking vertical contrast of a pink ribbon.

About the Portrait

William Merritt Chase (Figs. 1, 2) was born in Indianapolis, Indiana on November 1, 1849, and quickly became one of the most famous American Impressionist painters, enjoying considerable success during his lifetime. Chase biographer Carolyn Kinder Carr details his early success:

“Chase had exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1875, received a medal of honour at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and won critical attention for his portrait Ready for the Ride (1877; New York, Un. League Club), shown at the inaugural exhibition of the Society of American Artists.”

The painter traveled around the United States and Europe before he established himself at the Art Students League of New York and began a vigorous life of teaching and producing works of art. “Chase was one of the most conspicuous, influential painters of his time,” according to Nicolai Cikovsky Jr., curator of American painting at the National Gallery of Art.

Chase enjoyed great popularity due to his skillful incorporation of Baroque painting motifs and the Impressionist style. He was deeply inspired by and clearly emulated Baroque painters such as Anthony van Dyck, while simultaneously incorporating the stylistic influences of Impressionism, imitating artists such as Édouard Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and his American peer James McNeill Whistler. Chase’s portrait of Emmet is almost a direct copy of van Dyck’s Lord John Stuart and his Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart (Fig. 3) from the striking hand-on-the-hip pose to the highly contrasted color scheme. Chase’s inspiration can also be seen in other van Dyck paintings such as Charles I at the Hunt (Fig. 4), where the subject assumes a very similar pose.

“It’s a pose that, in the old masters’ [paintings, was] mostly given to men,” explains curator Erica Hirshler, of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. “And Chase takes that old master pose and he gives it to a new woman, a professional.”

Chase often made trips to Europe, participating in the Salons there, even winning an honorable mention in the Paris Salon of 1881, and coming into close contact with the French Impressionists. It was around this time that he met Whistler, whose influence is apparent among most of Chase’s work through the last part of the decade. According to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston:

“Chase greatly admired Whistler. After their meeting, he made a series of paintings of women in shimmering monochromatic color schemes that pay homage to Whistler’s aesthetic. Others pay homage to the past—among them is Chase’s striking portrait of his student, Lydia Field Emmet (1892, Brooklyn Museum), which presents her in a commanding pose often used in Old Master portraits of men, investing her with authority as she embarked on her own career.”

Chase painted many large-scale portraits, all of which are “characterized by a subtly modulated palette accented by shots of brilliant colour, a simple, soft and atmospheric background and brushwork that is lively but not overbearing” (Carr). This portrait of Lydia Field Emmet is one of the highly Impressionistic paintings done during this time.

Fig. 1 - William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916). Self Portrait, 1888. Pastel; 38.74 x 29.85 cm. Private Collection. Source: Wikiart

Fig. 2 - William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916). Self Portrait in 4th Avenue Studio, 1915-1916. Oil on canvas; 38.74 x 29.85 cm. Indiana: Richmond Art Museum. Gift of Warner M. Leeds and Richmond Art Museum Purchase, 1916. Source: Richmond Art Museum

Fig. 3 - Sir Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641). Lord John Stuart and his Brother, Lord Bernard Stuart, 1638. Oil on canvas; 237.5 x 146.1 cm (93.5 x 57.5 in). London: The National Gallery, NG6518. Source: National Gallery

Fig. 4 - Sir Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641). Charles I at the Hunt, 1635. Oil on canvas; 266.00 x 207.00 cm (104.7 x 81.4 in). Paris: Musée du Louvre. Source: Louvre

About the Sitter

Lydia Field Emmet was also an artist; in fact, she was one of Chase’s students (Fig. 5). It was not uncommon for Chase to paint his students and he often painted them in fashionable Impressionistic style. Emmet was a very successful artist, having a prosperous career and earning a living making art for upwards of 60 years (NGA). Emmet’s education began in Paris, where she and her sister enrolled at the Académie Julian. Later, she returned to New York and spent the next six years studying at the Art Students League where she studied under leading artists such as Kenyon Cox and Chase. Even after she finished school, Chase remained close to Emmet as he was impressed with her work, and soon appointed Emmet as an instructor at his unique Impressionism-focused Summer School of Art in Shinnecock, Long Island. Emmet’s career flourished during the 1890s and she exhibited regularly at the National Academy of Design, even painting one of the murals decorating the Woman’s Building at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, alongside other influential women artists like Mary Cassatt. It was during this time that Chase painted her portrait.

Chase gave a handful of his works to museums around New York City, which is how the Portrait of Lydia Field Emmet entered the Brooklyn Museum. It was becoming common for fashionable, young American women to be depicted with a hand on the hip; a pose paralleling that of women in bloomers riding bikes alluding to the depiction of an assertive, active, independent women. It is “a pose associated particularly in popular culture with ‘The New Women’ of the 1890s” (Hirshler). Chase painted others in similar poses as well, such as the portrait of Marietta Benedict Cotton (Fig. 6), who was a friend of his. He was keen to capture the women he looked up to in powerful, authoritative postures which aligned well with the trends in New York at the time. According to curator Erica Hirshler in a lecture regarding the William Merritt Chase exhibition at the MFA:

“Women had, even within them, considerable latitude. So, the women that Chase depicts are not only regarded as modern women but also in a lot of ways distinctly American. Their assertive actions, their freedom from tradition continuously… becoming entangled in the customs and conventions of European society. That native wit and courage was very much celebrated.”

This painting of Emmet, with all its power and Impressionistic flair, is an excellent example of who William Merritt Chase was as an artist.

Fig. 5 - Lydia Field Emmet (American, 1866-1952). Self-portrait, 1912. Oil on canvas; 63.5 cm x 76.2 cm (25 in x 30 in). New York: National Academy of Design. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 6 - William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916). Lady in Black, 1888. Oil on canvas; 188.6 x 92.2 cm (74 1/4 x 36 5/16 in). New York, New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.11. Gift of William Merritt Chase, 1891. Source: The Met

William Merritt Chace (American, 1849–1916). Lydia Field Emmet, 1892. Oil on canvas; 72 x 36 1/8 in. (182.9 x 91.8 cm.) New York: Brooklyn Museum, 15.316. Gift of the artist. Source: The Brooklyn Museum

About the Fashion

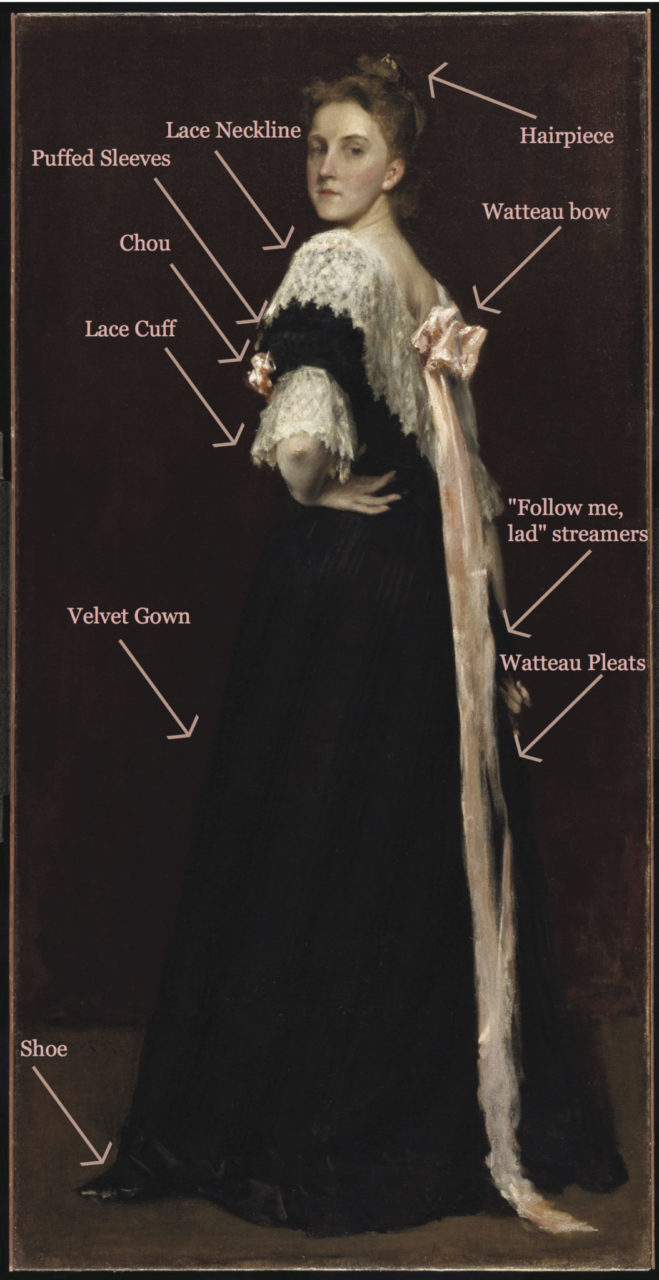

At the beginning of the 1890s, fashionable women abandoned the exaggerated bustle of the 1880s and instead looked back on previous decades for inspiration. Large leg-of-mutton sleeves soon became popular; however, this portrait was painted during was a transitional moment when high fashion embraced slimmer silhouettes. Emulating the work of Old Masters, Chase paints Emmet wearing black as a fashionable color and immediately catches the viewer’s attention with the shocking vertical contrast of a loosely painted pink ribbon.

Chase had an eye for fashion equivalent to that of van Dyck or Claude Monet. Emmet wears an elegant ensemble which is fashionable for early 1890s dress. The dress is black, though she is not in mourning, which is made clear by the contrasting white lace at the collar and cuffs, as well as the bright pink ribbon streamers that cascade down her back. She is wearing black as a fashionable color, as many women had before her, including Charles Carolus-Duran’s wife in his celebrated Lady With the Glove exhibited to great success at the 1869 Salon (Fig. 7) and which Chase could have seen in Paris as it was bought by the French state in 1875.

Emmet’s dress embodies several fashionable characteristics seen in 1892. The black dress is slim-bodied, rendered so it appears to be made out of rich black velvet either appliquéd with satin stripes or pleated, which were two fashionable dress manipulations at the time. The dress is identified as being velvet by curator and Chase expert Erica Hirshler and, according to Harper’s Bazaar in January 1892, velvet was a fashionable fabric for winter party gowns:

“Black velvet is also worn by young and beautiful women; one gown especially admired being of princesse shape.” (63)

The dress also appears to subscribe to the “princesse shape”, a very fashionable 1890s silhouette. The princesse shape, more often than not accompanied by Watteau pleats, was a revival of an 18th-century French fashion (Fig. 9). The sack-back gown or robe à la française, a loose dress with Watteau pleats, became extremely popular in the 1740s-50s. The style came back, in a much more subdued silhouette and became a popular eveningwear trend in the early 1890s. It’s difficult to discern if Emmet’s dress features Watteau pleats, but prominent pink ‘follow-me-lad’ streamers cascade from the bow between her shoulders–such streamers often appeared with the Watteau pleats.

Fig. 7 - Charles Carolus-Duran (French, 1837-1917). The Lady with the Glove, 1869. Oil on canvas; 228 × 164 cm (89.7 × 64.5 in). Paris: Musée d'Orsay, RF 152. Source: Orsay

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (French). Robe à la française, 1775–1800. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.61.13.1a, b. Purchase, Irene Lewisohn Bequest, 1961. Source: The Met

Diagram of referenced dress features.

Source: Author

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode Illustrée, 1892. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library. Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

Fig. 11 - Adele-Anaïs Colin Toudouze (French, 1822-1899). La Mode Illustrée, no. 32, 1892. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library. Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

Fig. 12 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode Française, no. 12, 1891-1892. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Costume Institute, b17520939. Gift of Woodman Thompson. Source: The Met

These “follow-me-lad streamers” as curator Hirschler describes them can be seen throughout European fashion plates of the decade, emphasizing them as truly fashionable. Ribbons cascading from the back at the Watteau pleat as well as ribbons streaming out from anywhere at the back of the dress (Fig. 10), or even flowing to the ground form the side of the waistband (Fig. 11) all feature regularly in fashion periodicals. La Mode Française gives an excellent example of a very fancy princesse dress with long contrasting ribbon steamers (Fig. 12). The ribbon is tied in a bow at the center of the shoulder blades, just as the ribbon on Emmet’s dress, and is attached where the lacy decoration ends. The ribbons in the plate fall over the Watteau pleat and the same can be assumed for Emmet’s dress. The gold dress in the German fashion plate Der Bazar (Fig. 13) possesses similar characteristics, being a princesse dress with Watteau pleats and a cascading ribbon, although here the ribbon is of the self-fabric instead of a contrasting color and/or fabrication which was most popular. Harper’s Bazaar in February 1892, in particular, has a lot to say about the trend:

“Watteau princesse dresses for the house are imported in the changeable surah silks, combined with écru point de Gênes lace set down each side from top to foot, with trimmings of velvet ribbon. The front is straight, its fullness shirred to a standing collar, then caught in at the waist by a belt of velvet ribbon, which starts under a chou next the Watteau fold in the back, and crossing the front, meets another chou on the other side of the flowing fold. A long end of the ribbon falls from each chou to the foot of the skirt. The Watteau fold is shirred to a narrow point just below the collar, and widens gradually to be lost in the skirt. Large puffs of silk form the tops of the sleeves, and are gathered to closely fitted lace sleeves. The high collar band is covered with lace, and a row of velvet ribbon set at the top to fasten at the back under a chou. This is prettily carried out in pink and green changeable surah that is dotted with black, white, and green.” (163)

Fig. 13 - Illustrirte Damen-Zeitung Illustration Der Bazar (German). Fashion Plate 454, April 1892. Berlin: Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf. Source: Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf Digital Resources

Fig. 14 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode Illustrée, 1892. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library. Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

The large puffed sleeves, the rosettes on the chest, also known as chou, and lace details emphasized in the periodical also make an appearance in many fashion plates and in the portrait of Emmet. Both previously mentioned fashion plates sport the iconic 1890s puffed sleeve, however both display high necklines, an example of modesty. In the Portrait of Lydia Field Emmet, she sports a dramatic low neckline that dips down in the back and can be assumed to do the same in the front from a small piece of lace peeking out from the curve of her chest, right above the chou. More dramatic styles such as these can be seen on young women in 1892 La Mode illustrée fashion plates. For example, a woman in evening dress can be seen wearing a low, open neckline (Fig. 14), and many fashionable ladies wear similarly revealing dresses in a full-page ball gown spread (Fig. 15). All of these necklines have one other thing in common; they are all trimmed in a long contrasting lace ruffle as in Emmet’s dress.

Fig. 15 - La Mode Illustrée (French). Toilette de Bal, 1892. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library. Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

This lace ruffle trims not only the neckline but also the cuffs of the sleeves. The puffy leg-of-mutton sleeve was a revival of earlier fashion as well, the return of a popular 1830s trend where the sleeves were huge–almost to the point of sagging at the upper arm and tapered to a skinny long sleeve to the wrist (Fig. 16). In 1892, it was common to see women wearing their sleeves in a less exaggerated yet long 1830s style but also in a more updated, shorter style; see, for example, the white dress on the left in an 1892 La Mode illustrée fashion plate (Fig. 17). These shorter sleeve designs, like that on the woman in white, all have a lacy or ruffled trim at the hem of their sleeve, something very prominent in the portrait of Emmet. In fact, it seems to be extremely uncommon to find a shorter puffed sleeve without lace trim. Emmet’s lace, however, is of contrasting color and texture–a fashionable choice. An albumen cabinet card photograph of Lady Randolph Churchill (Fig. 18) displays this contrasting-lace-against-puffy-sleeve trend perfectly and although she does not have lace trim at the sleeve like Emmet, she does sport contrasting chous very similar to those suggested in the portrait.

Emmet wears few accessories; apart from the small glint of some sort of hair decoration and her simple black shoes, she seems to have decorated herself rather plainly. She is not wearing, nor even holding, a pair of gloves. The contrasting chou on the dress and exuberant lace might have been enough for her fashion taste. Her hair is done up in a simple style, probably a bun or curled up-do of sorts similar to those seen in an 1892 La Mode illustrée fashion plate (Fig. 19), with a decorative pick stuck in the top of it. In addition to an absence of accessories, Emmet also seems to lack a voluminous petticoat. Her dress is A-line and crumples limply at her feet suggesting that no support is worn underneath. Nonetheless, she almost certainly would have been wearing a corset as was typical of the time.

Based on all the fashionable details captured in this portrait, it is fair to say Lydia Field Emmet is appropriately dressed for an evening event. Though the background is nondescript in its Impressionist style, the fashion itself distinguishes the context. Most fashion plates previously discussed show women wearing almost identical dresses in festive ballroom settings. Both the dress and the pose suggest a powerful, authoritative woman with a strong sense of self. Emmet’s success and confidence as a modern woman shines through clearly, emphasized by her obvious sense of personal style, captured well in the portrait by Chase.

Fig. 16 - Designer unknown (American). Dress, 1837. Silk. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 37.192. Rogers Fund, 1937. Source: The Met

Fig. 17 - Artist unknown (French). La Mode Illustrée, no. 29, 1892. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library. Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

Fig. 18 - W. & D. Downey (English). Jeanette ('Jennie') Churchill (née Jerome), Lady Randolph Churchill albumen cabinet card, 1893 or before. Photograph; 150 mm x 100 mm cm (5 7/8 in x 3 7/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 19 - Adele-Anaïs Colin Toudouze (French, 1822-1899). La Mode Illustrée, no. 3, 1892. Tokyo: Bunka Gakuen Library. Source: Bunka Gakuen Library

References:

- “1890s in Western Fashion.” Wikipedia, March 3, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=1890s_in_Western_fashion&oldid=828531862.

- Brooklyn Museum. “Lydia Field Emmet.” Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/68.

- Carr. “Chase, William Merritt | Grove Art.” Accessed April 28, 2018. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000016128.

- Gernsheim, Alison. Victorian & Edwardian Fashion: A Photographic Survey. New York: Dover Publications, 1981. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868281359

- Hirshler, Erica. “William Merritt Chase’s Modern Women.” Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Accessed May 1, 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I4wZpYERYug.

- Lyall, Sarah. “Chase’s Art Glows Anew.” The New York Times, September 6, 1987, sec. N.Y. / Region. https://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/06/nyregion/chase-s-art-glows-anew.html.

- “Lydia Field Emmet.” National Gallery of Art. Accessed April 28, 2018. https://www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1267.html.

- Milbank, Caroline Rennolds, and Harold Koda. Fashion: A Timeline in Photographs: 1850 to Today. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc, 2015. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1028511118

-

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. “Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Opens Landmark Exhibition of William Merritt Chase.” Accessed March 15, 2022. https://www.mfa.org/news/william-merritt-chase.

- “New York Fashions,” Harper’s Bazaar, January 28, 1892, 63. http://hearth.library.cornell.edu

- “New York Fashions,” Harper’s Bazaar, February 27, 1892, 163. http://hearth.library.cornell.edu

- Pisano, Ronald G. William Merritt Chase. New York: Watson-Guptill, 1979. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4983286

-

Pisano, Ronald G., D. Frederick Baker, and Marjorie Shelley. William Merritt Chase: The Complete Catalogue of Known and Documented Work by William Merritt Chase (1849-1916). New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/162471316

- Stamberg, Susan. “Meet William Merritt Chase, The Man Who Taught America’s Masters.” NPR.org, June 28, 2016. https://www.npr.org/2016/06/28/483231216/meet-william-merritt-chase-the-man-who-taught-americas-masters.