The Little Foxes (1941)

Synopsis

This film adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s play involves the corrupt dealings of a wealthy Southern family at the turn of the 20th century. The vicious Regina Giddens and her two greedy brothers scheme mercilessly in their attempt to make a fortune on a new cotton mill.

Directed by

William Wyler

Release date

29 August 1941

Costume Designer

Orry-Kelly

Studio

Samuel Goldwyn Productions, Inc.

Source: IMDb

Film trailer

Introduction

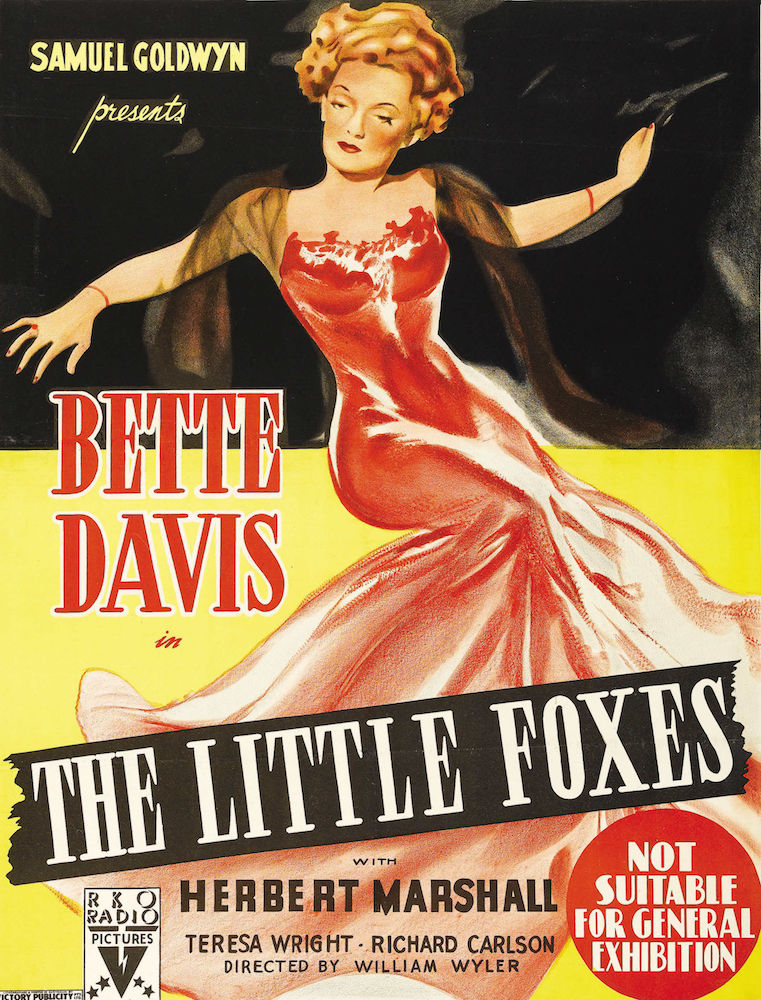

Based on the successful Broadway play by acclaimed American playwright Lillian Hellman, The Little Foxes (1941) tells a bitingly sinister story of American greed at the turn of the twentieth century. The rights to the play were purchased by producer Samuel Goldwyn, who made a triumphant return to movie-making after leaving United Artists in 1940. He would secure Bette Davis’s only loanout while she was under contract with Warner Brothers to make this film adaptation, and he used her star power as a vehicle to market the picture. Davis led a cast that included five actors who reprised their roles from the original Broadway production (Patricia Collinge, Charles Dingle, Carl Benton Reid, Dan Duryea, and John Marriott), who made their screen debuts alongside young newcomers Teresa Wright and Jesse Grayson (American Film Institute). The Little Foxes premiered at Radio City Music Hall on August 21, 1941 to a record opening day audience of 22,163 eager viewers and received critical acclaim (“Film Record Set by ‘Little Foxes’” 7). The New York Times applauded the adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s melodrama, which had been “translated to the screen with all its original viciousness intact and with such extra-added virulence as the relentless camera of Director William Wyler and the tensile acting of Bette Davis could impart” (Crowther 19). The film garnered nine Academy Award nominations: Best Picture, Best Screenplay, Best Music Scoring of a Dramatic Picture, Best Film Editing, Best Directing, Best Art Direction, Best Actress in a Leading Role for Bette Davis, and Best Supporting Role for both Patricia Collinge and Teresa Wright (American Film Institute).

About the Period Setting

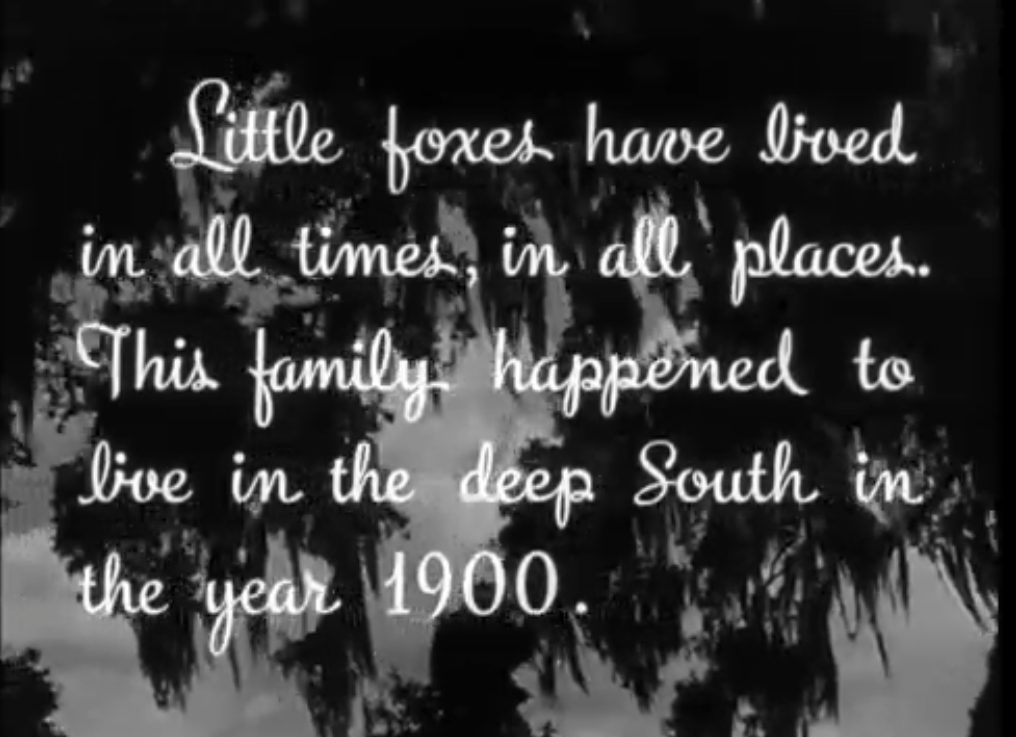

T he Little Foxes opens with a title card (fig. 1) that places the viewer “in the deep South in the year 1900.” All filming took place on the studio lot, save for the exterior shots filmed on location at the Belle Helene Plantation near Baton Rouge, Louisiana—which perfectly set the scene for Hellman’s tale of Southern avarice. The film adaptation was able to extend beyond the walls of the living room that contained the drama in the Broadway play, because director William Wyler “had advantage of an entire six-house village square built inside a studio soundstage” (“On Set with The Little Foxes” 10).

Fig. 1 - Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Opening title card from The Little Foxes, 1941. Source: Author

The social climate of the early twentieth century proves the driving force behind the film’s plot. The story focuses on the struggle of a female “Southern aristocrat” to attain wealth and freedom in a society where a father’s fortune could only be inherited by his sons. The family’s wealth comes from their dealings in trade, making them more akin to industrialists than proper aristocrats—who were defined as members of old, landed, plantation-owning families. Only the protagonist’s sister-in-law, Birdie, is able to claim the title of “aristocrat,” and therefore the other characters work tirelessly to attain enough wealth to earn comparable prominence in Southern society. Desperate to have the family fortune for herself, the protagonist, Regina, resorts to merciless scheming against her corrupt brothers and subverts the expectations of feminine behavior that prevailed in the year 1900. What results is “a realistic, disagreeable, unpleasant drama — but an engrossing one” (Hanna 6).

About the Character

At the heart of the text, Regina Giddens is an unrelentingly ambitious anti-heroine, and her imposing character has drawn many actresses to the role since the play debuted on Broadway in 1939. Since then, she has been brought to life by such leading ladies as Tallulah Bankhead in the original Broadway production (fig. 2), Bette Davis in the film adaptation, Elizabeth Taylor in the 1981 Broadway revival (fig. 3), and most recently by Laura Linney and Cynthia Nixon in 2017, in a unique Broadway production that allowed the two women to alternate in the coveted role (fig. 4). Deliciously evil and challengingly complex, the role of Regina Giddens has endured the test of time and gained a reputation for being, as Laura Linney put it: “catnip for actresses of a certain age.” Tallulah Bankhead was lauded for her impassioned portrayal of Regina in the original Broadway production—most notably, by Bette Davis, who attended the play at William Wyler’s insistence. After witnessing Bankhead’s performance, Davis felt compelled to bring a different interpretation of the character to the film adaptation. Where Bankhead’s Regina was fiery and vicious, Davis’ Regina was cold, calculating, and comparatively understated. Both manifestations of the character were supported by the script, and each appropriate for the medium through which it was being performed. It is not to say that Bette Davis’ performance was lacking in venom. Critics reveled in her interpretation of Regina, saying, “Beneath her Gibsonian pompadour there’s a modern, more self-centered Lady Macbeth, her mind and her heart full of daggers” (Hamilton 5). The public, too, expressed their excitement in such fan magazines as Modern Screen, claiming that “it seems the most natural thing in the world to see her playing the leading role in Samuel Goldwyn’s film, The Little Foxes!” (“Bette Davis” 24). Indeed, Bette Davis was completely in her element in this picture. She had become famous for playing ill-tempered women in sumptuous historical dress, and this was exactly the type of role that her fans loved to see her in. It was costume designer Orry-Kelly who helped to shape this star persona after repeated collaborations with Davis on period films; therefore, he had an integral role in delivering a vision of Regina Giddens that would meet the audience’s high expectations (Jorgensen and Scroggins, 170).

Fig. 2 - Unknown. Tallulah Bankhead as Regina Giddens in the original Broadway production of The Little Foxes, 1939. Source: Film for Fancy

Fig. 3 - Unknown. Elizabeth Taylor as Regina Giddens in the Broadway revival of The Little Foxes, 1981. Source: Playbill

Fig. 4 - Unknown. Cynthia Nixon and Laura Linney alternate in the role of Regina Giddens in Manhattan Theatre Club's production of The Little Foxes, 2017. Directed by Daniel Sullivan. Source: The New York Times

About the Costumes

Orry-Kelly’s costumes do just as much to establish the specific time period of the film’s setting as the opening title card—with the unmistakable corseted bodices, swirling skirts, and lofty hairstyles that prevailed in fashionable dress at the turn of the twentieth century. William Wyler insisted on historical accuracy in other aspects of the film, yet he demanded unrealistically lavish costumes for his leading lady, whose star power remained the driving force of the picture’s production. Bette Davis disagreed with the director’s vision of her character’s appearance, and Orry-Kelly sided with Davis as she fought Wyler on Regina’s excessively opulent wardrobe. Wyler instructed Orry-Kelly to dress Davis “in the height of Gibson Era fashions, [to coincide] with the story’s 1900 setting”; however, designer and actress were “in accord that Regina’s clothes would have, as Davis put it, ‘a certain worn out look from a few years back’ ” (Jorgensen and Scroggins, 170). When Wyler refused to compromise, Davis walked off the picture in protest and did not return for a week. Rumors flew in fan circles, which led Photoplay Magazine to speculate that it was “the uncomfortableness of her costumes” that contributed to Bette’s dramatic departure from the set (York 8). Eventually she relented, and appeared in the sumptuous fashions that ultimately satisfied both her director’s wishes and her fans’ desire for the nostalgic glamour that they had come to expect from her. Though the costumes were inaccurate to the situation of the character, they suited the styles of the time period. Women’s Wear Daily wrote the following of Davis upon the film’s release: “She has the figure for [the clothes of the period], and adopts just the proper carriage for the overpowering pompadour, the high-boned collars, the boned corseted, wine-glass figure, and the swishing trains that the 1900 ladies lead around all day long” (“Boldini Type Clothes” 4). Strict rules that dictated the appropriateness of dress for different times of day were established by the early Victorian era, and still firmly in place at the time of the film’s setting. Orry-Kelly aptly adheres to these conventions in his designs, which affords the audience the opportunity to observe a variety of costumes that span from morning until evening.

Fig. 5 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

Fig. 6 - Unknown. Bette Davis on the set of The Little Foxes, 1941. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: The Bette Davis Estate

Underwear / Dressing Ensemble

The fashionable silhouette of the period was shaped by the corset, which had reached its most severe shape around the year 1900. Preston Remington, curator of the Exhibition of Victorian and Edwardian Dresses at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1939, commented, “If the dresses of the early 1900’s display any suggestion at all of exaggeration, it may be accredited to the mode of corseting” (Remington 5). He acknowledges the distinctive silhouette of tun-of-the-century fashions as a significant departure from contemporary body ideals, explaining the general public’s proclivity to associate such shapes with the past. A woman of Regina’s position would surely rely on corsetry to communicate her participation in fashion at all hours of the day; however, the audience is only granted the briefest glimpse of one early in the film (fig. 5). She sits at her vanity arranging her hair and wears an open dressing gown that reveals the hint of a corselet beginning just under her breasts. Before long, she is prepared to receive guests, with her flowing white dressing gown arranged to perfection. It appears to be two pieces: a short type of embroidered bed-jacket with wide, winged sleeves, over a bell-shaped petticoat with tiers of ruffled lace at the hem (fig. 6). This dramatic look conveys the same flavor of movie-star glamour as would a 1940s negligee, while still managing to evoke romantic notes of the past.

Breakfast Ensemble

An ensemble worn during a breakfast scene is perhaps Regina’s most realistic look throughout the film (fig. 7). The costume was featured in Women’s Wear Daily, and described as “a screen printed silk shirtwaist with high collar and jabot, worn with a green flannel skirt, cut on bell silhouette with a deep flounce at bottom” (“Early 1900s Styles” 3). Though relatively understated, the blouse is meticulously constructed, with tiny pintucks at the center front, delicate lace trimming at the neck, and softly gathered fullness at the sleeves. Orry-Kelly has given her a wide, hard belt to accentuate the waist and a circular brooch at the neck to secure the lace jabot.

Fig. 7 - George Hurrell (American, 1904-1992). Bette Davis as Regina Giddens in a publicity photograph for The Little Foxes, 1941. Costume design by Orry-Kelly. Source: IMDb

Fig. 8 - George Hurrell (American, 1904-1992). Bette Davis in a publicity photograph for The Little Foxes, 1941. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 9 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

Walking Suit with Hat

For the film’s dramatic climax, Bette Davis is outfitted in a fashionable walking suit of rose beige wool elaborately trimmed with matching passementerie braid, as described in Women’s Wear Daily (“Fashions Worn in the New Films” 3). She is a commanding presence, as she enters the house from an afternoon out wearing a tailored jacket with broad shoulders and a shapely peplum (fig. 8). An imposing, wide-brimmed hat completes the silhouette. It features a stuffed bird—a quintessential design feature in turn-of-the-century millinery. Because California conservation laws prevented the use of stuffed birds on hats in the 1940s, “Orry-Kelly borrowed a huge white dove, the epitome of taxidermist art, from the Louisiana Museum. Here perched the snowy fowl on a huge picture hat that featured a dotted veil” (Davis 157). Davis later removes the fitted jacket and performs the last scene in a high-neck shirtwaist blouse with ruffled lace trim and a large jabot. The waist is cinched with a wide belt, and the elegant seaming of the gored skirt is visible as she moves up and down the stairs (fig. 9).

Evening Dresses

Regina is portrayed at the height of glamour in a pivotal dinner scene, in which she entertains a wealthy Chicago businessman interested in forming a partnership with her family. She wears a striking black velvet strapless evening gown trimmed with jet bead appliques bordering the décolletage, shoulders veiled in a gossamer point d’esprit net scarf. It photographed exceptionally, and was a favorite in promotional imagery for the film (fig. 10). It was, however, not without it complications. Modern Screen magazine reported: “Chief trouble maker among authentic Edwardian period gowns designed by Orry-Kelly, this black velvet, bead-trimmed creation necessitated use of flesh-pinching corsets, brought on Davis collapse” (“On Set with The Little Foxes” 8). Whatever discomfort this dress caused Davis, it greatly informed her performance by governing her posture and movement. After dinner, she lounges on the sofa with an erectness afforded by her corseted bodice (fig. 11), effectively conveying her character’s haughtiness and poise, even at a moment of rest. Modern Screen noted Regina’s other evening frocks, which included “a gown of black taffeta and lace, and one of white lace, both heirlooms” (“On Set with The Little Foxes” 8). The editorial does not elaborate on this claim, though both gowns bear a passing resemblance to authentic clothes from the period. The black taffeta dress is briefly seen, and appears somewhat anachronistic in relation to the rest of Orry-Kelly’s designs for Regina (fig. 12). It has an embellished lace yoke and a high collar that opens to a point at the base of the neck. These odd design features were not lost on Women’s Wear Daily: “There is one departure in this completely throttled look in one collar reviving a variation of the Medici collar” (“Boldini Type Clothes” 4). Ultimately, this would be more accurately classified as an afternoon dress, with it’s long sleeves and high collar.

Fig. 10 - George Hurrell (American, 1904-1992). Bette Davis in a publicity photograph for The Little Foxes, 1941. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: MPTV Images

Fig. 11 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

Fig. 12 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

The final evening dress worn by Bette Davis is made of heavy battenberg-type lace with a wide, off-the-shoulder neckline and short sleeves that have the effect of a bertha (fig. 13). It is cut close to the body, and fishtails out into an elegant, trailing skirt. This “so-called princess dress, [was] favored for formalwear in this period” due to its “graceful, unbroken flow” (Remington 5). An article in Women’s Wear Daily seems to uphold Modern Screen’s claim that this gown was indeed an heirloom from the turn-of-the-century. It describes the garment in detail, stating: “Most elaborate is a beautiful white lace gown made from 10 yards of rare lace especially created in Paris for the original owner. In order not to cut the lace more than necessary, the entire skirt is in one piece” (“Fashions Worn in the New Films” 3). From this, it can be discerned that the dress worn by Bette Davis was either an original garment from the period that had been altered for the film, or else a new garment reconstructed from the original textile.

Fig. 13 - Unknown. Bette Davis in a publicity photograph for The Little Foxes, 1942. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: "Dressed: A Century of Hollywood Costume Design" by Deborah Nadoolman Landis (New York: Harper Collins, 2007)

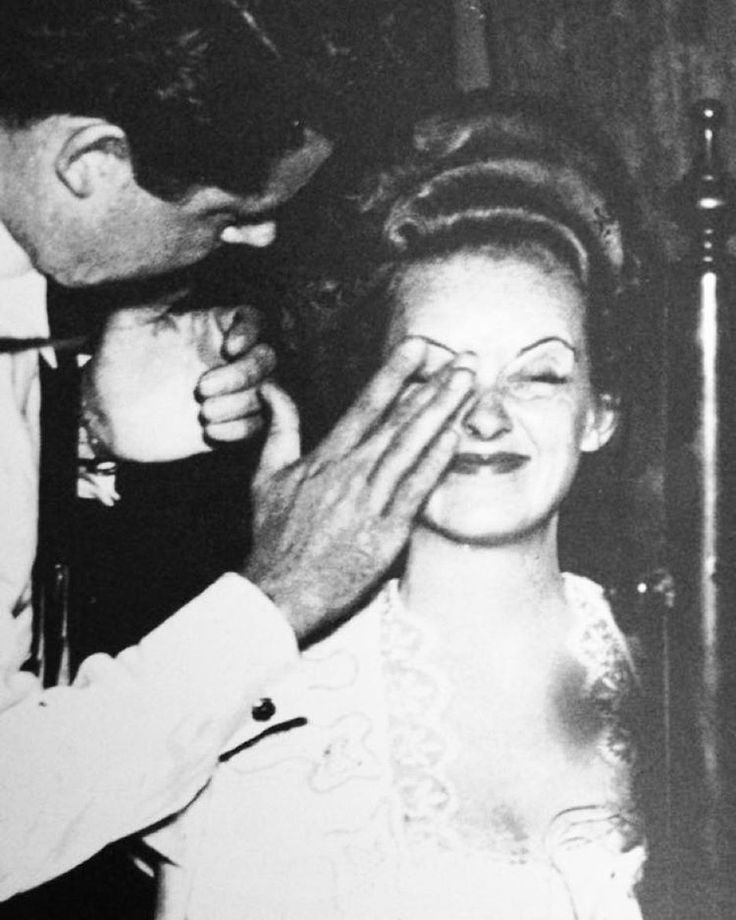

Fig. 16 - Unknown. Warner Brothers make-up artist Perc Westmore applies white foundation base to Bette Davis on the set of The Little Foxes, 1941. Featured in "Modern Screen" Magazine, October 1941. Source: Media History Digital Library

Hair and Make-up

Hair and make-up were crucial in transforming 32-year-old Bette Davis into the hard-faced, 40-year-old Regina Giddens. A stylized updo did most of the heavy lifting in the creation of the turn-of-the-century Southern matriarch (fig. 14). The incredible height achieved by the film’s hair stylist aligns Bette Davis with those iconic women illustrated by Charles Dana Gibson in the early 1900s (fig. 15). Reports from the set claim that the “becoming pompadour hairdress [required] 48-minute work each morning” (“On Set with The Little Foxes” 9). To help create the illusion of middle age, Davis requested that make-up artist Perc Westmore exaggerate the fashionable pallor of the period. Instead of conventional foundation, he used a plain white base to offset saturated lips, thin eyebrows, and long lashes (fig. 16). Cinematographer Gregg Toland then used harsh lighting to even further emphasize Regina’s icy visage, causing William Wyler to liken Davis’ look to that of a Kabuki performer (International Movie Database).

Fig. 14 - George Hurrell (American, 1904-1992). Bette Davis in a publicity photograph for The Little Foxes, 1941. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Make-up by Perc Westmore. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 15 - Charles Dana Gibson (American, 1867-1944). The Weaker Sex, 1903. Ink on paper. Source: "The Weaker Sex: The Story of a Susceptible Bachelor" (New York: Scribner’s, 1903)

About the Costume Designer

A s the in-house costume designer at Warner Brothers during the height of the studio era, Orry-Kelly (born Orry George Kelly, 1897–1964) was tasked with designing both period and contemporary films. His skill for creating costumes that drew on both past and present earned him great acclaim, and he was influential in establishing the authority of the Hollywood costume designer in the rise of the American fashion industry during the interwar years. He worked closely with actresses in crafting their star personas—creating memorable looks for fashionable ladies like Kay Francis, Ava Gardner, and Marilyn Monroe. But no collaboration proved more prominent in his career than that with Bette Davis. It is reported that “Orry-Kelly and Bette Davis made an astounding total of forty-six movies together during a period of fourteen years” (Jorgensen and Scroggins, 170). Between Jezebel (1938), Dark Victory (1939), Now, Voyager (1942), and Mr. Skeffington (1944), they worked together to create fashionable characters from a range of time periods (fig. 17-19). Throughout their partnership, Orry-Kelly became a master at designing clothes for Bette Davis’ somewhat unconventional figure. Unlike other stars of the era, her body was challenging to dress, mostly due to her large breasts. In a documentary that chronicles Orry-Kelly’s illustrious career, Women He’s Undressed (2015), costume historian David Chierechetti describes the designer’s experience in dealing with Davis’s figure: “Kelly wanted to give her bras that had underwire in them to push her up, but she wouldn’t allow him to use any wire because she thought it would give her breast cancer. And so he had to make [special] undergarments for her that pushed them up as far they could go.” Surely, the corsets required for period dress must have been problematic throughout their working relationship, but Orry-Kelly’s aptitude for design prevailed in film after film. “‘I think of Bette Davis as a period piece,’ Orry-Kelly said. ‘She belongs in costume clothing.’ ” (Jorgensen and Scroggins, 170). Ultimately, they proved to be hugely indispensable to each other in their respective careers at Warner Brothers, and theirs is a partnership cherished by Hollywood historians. Acclaimed costume designer Ann Roth says in the documentary, “It was a good marriage. Orry was very in tune with her…he loved her, and she loved him. And rightfully so” (Women He’s Undressed, 2015).

Fig. 17 - Unknown. Bette Davis in a publicity photograph for Jezebel, 1938. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: IMDb

Fig. 18 - Unknown. Bette Davis in a publicity photograph for Dark Victory, 1939. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: IMDb

Fig. 19 - Unknown. Bette Davis in a publicity photograph for Mr. Skeffington, 1944. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: IMDb

About the Production Design

Fig. 20 - Unknown. Bette Davis on the set of The Little Foxes, 1941. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Art direction by Stephen Goosson. Source: IMDb

Fig. 21 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

In relation to the film’s costume design, the same design principles were upheld to satisfy William Wyler’s vision for the world of The Little Foxes. Under the art direction of Stephen Goosson, a splendid residence was erected in which most of the film’s action would take place. Much like their arguments over Regina’s costumes, Davis and Wyler fought about the set designs, which she accused of “being too lavish, arguing that they should have been done in a style of decaying grandeur to reflect her character’s diminished lifestyle after failing to inherit family wealth along with her brothers” (Jorgensen and Scroggins, 170). Nevertheless, a visual unity between sets and costumes prevails, with the foliate scrolls of the wallpaper echoing the embroidered motifs of Regina’s clothing (fig. 20). Set decorator Howard Bristol and cinematographer Gregg Toland establish a strong pattern of shots throughout the film in which the leading lady is perfectly framed with parted curtains (fig. 21-25). This technique not only heightens her character’s prominence, but conveys a sense of staged grandeur that abounds in every aspect of the film’s production. The final shot is a close-up of Regina staring out a window, in which the curtains cut in close on either side of her face—underscoring the solitude in which she is left after her successful scheming (fig. 26). The irony lies in the overwhelming constriction of the shot, despite Regina’s newfound freedom. Between the high-necked lace collar and elegant window dressings, she is entombed by her own finery.

Fig. 22 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

Fig. 23 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

Fig. 24 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

Historical Accuracy

T he Little Foxes makes a concerted attempt at historical accuracy, and it is clear that Orry-Kelly referred to images of prominent turn-of-the-century socialites as inspiration for Regina’s costumes. The likes of Edith Vanderbilt, Alva Belmont, and Catherine Neilson were often depicted wearing such ensembles as those worn by Bette Davis in the film. A photograph in the collection at the Museum of the City of New York shows the future Mrs. Reginald C. Vanderbilt sitting for portraitist Richard Hall, in a white dress with exposed décolletage, flowing sleeves, and ruffled skirt hem (fig. 27). With hair piled high in an upswept pompadour, she bears a remarkable resemblance to Regina Giddens in her glamorous dressing gown. Such prominent aristocrats in urban society would have been far more fashionable than a wealth-chasing woman from a small Southern town, but Goldwyn’s production relied on such sources of inspiration to successfully create a glamorized version of the past fit for the screen.

Fig. 27 - Byron Company (New York). Richard Hall and Mrs. Reginald C. Vanderbilt, 1903. Gelatin silver print; (10 1/4 x 8 3/8 in). The Museum of the City of New York, 93.1.1.18429. Source: The Museum of the City of New York

Dressing Ensemble

An extant example of a white morning dress dating to ca. 1902 exists in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection (fig. 28). Like Regina’s dressing ensemble, it consists of two pieces: a loose bed jacket with voluminous ruffles adorning the neck edge and sleeve cuffs, paired with a matching skirt. The silhouette is consistent with a typical tea gown, a garment associated with women of the American leisure class in the early 1900s. The Met’s example is made of a lightweight cotton, which would have been appropriate for the Southern climate in which the film is set. However, the garment that Bette Davis wears in the film appears to have been fabricated from a semi-sheer silk, which reads as a more luxurious textile on film.

Fig. 28 - Designer unknown (American). Morning dress, ca. 1902. Cotton. New York: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.461a, b. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Charles C. Harris, 1968. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

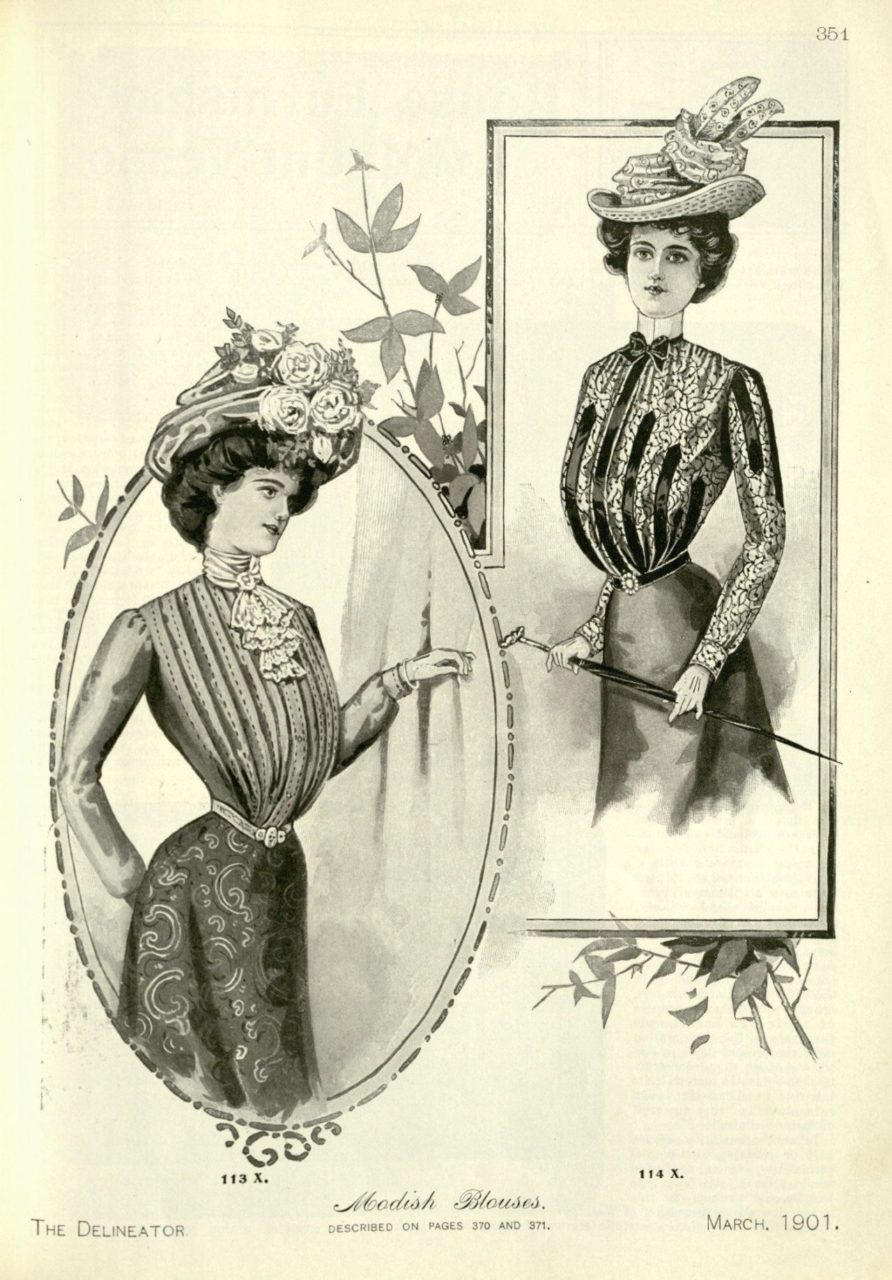

Fig. 29 - "Modish Blouses". The Delineator, March 1901. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Library

Breakfast Ensemble

At the turn of the twentieth century, the shirtwaist was ubiquitous in daytime apparel and fitting for the casual breakfast scene at the opening of the film. An egalitarian garment worn by both working class and upper class, it boasted infinite possibilities in the way of fabrication and embellishment. Such “modish” examples were shown in fashion magazines such as The Delineator (fig. 29), with delicate prints and elaborate trimmings that would have appealed to a woman of Regina’s class.

Afternoon Suit with Hat

A very similar afternoon ensemble to that which Regina wears in the latter part of the film can be seen in a fashion plate from the March 1901 issue of The Delineator—down to the embellished lapels and dotted veil (fig. 30). The overall impression of Davis’ costume is entirely convincing as a turn-of-the-century walking suit. However, the design’s inaccuracy lies in the upper half of the silhouette. Betrayed by the modernity of its tailoring, Regina’s jacket is more akin to a fitted 1940s blazer than an Edwardian monobosom bodice. Another small detail that could reveal the year of the film’s creation is the shape of the hat which Regina removes upon entering the living room. At first, it appears to be an aptly rendered reproduction of Edwardian millinery —complete with wide brim, stuffed bird, and elaborate trimming. However, we catch a glimpse of the top of the hat as she take it off, which has a tall, cone-like crown characteristic of fashionable 1940s styles (fig. 31).

Fig. 30 - "Stylish Eton Suits". The Delineator, March 1901. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Library

Fig. 31 - Unknown. Screen capture from The Little Foxes, 1941. Samuel Goldwyn Productions. Source: Author

White Lace Evening Dress

Another more historically accurate costume in the film, the white lace evening gown bears patent similarities to a dress featured in the 1939 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Exhibition of Victorian and Edwardian Dresses (fig. 32). They share a low-cut neckline with a slight sweetheart shape, and both boast an uninterrupted line from bust to hem, which skims over the contoured body. It is entirely plausible that the dress worn by Bette Davis was indeed a genuine garment from the period. The scale and texture of the lace is distinctive of those Irish crochet lace dresses that “had an unprecedented vogue in the early years of the twentieth century” (Lester and Oerke 530). The flounced sleeves were typical design features on such evening dresses, and balanced the flare of the skirt while emphasizing the narrowness of the waist (fig. 33).

Fig. 32 - Unknown. Evening dress, ca. 1907. Irish crochet lace. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 25.278.7. Bequest of Mrs. Heinrich Meyn, for her friend, Anna Mary King, 1925. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute Library Archives

Fig. 33 - Charles Klein (French). Lace evening dress, ca. 1910. Cotton, silk. New York: Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.300.1283. Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Maxime L. Hermanos, 1961. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Black Velvet Evening Gown

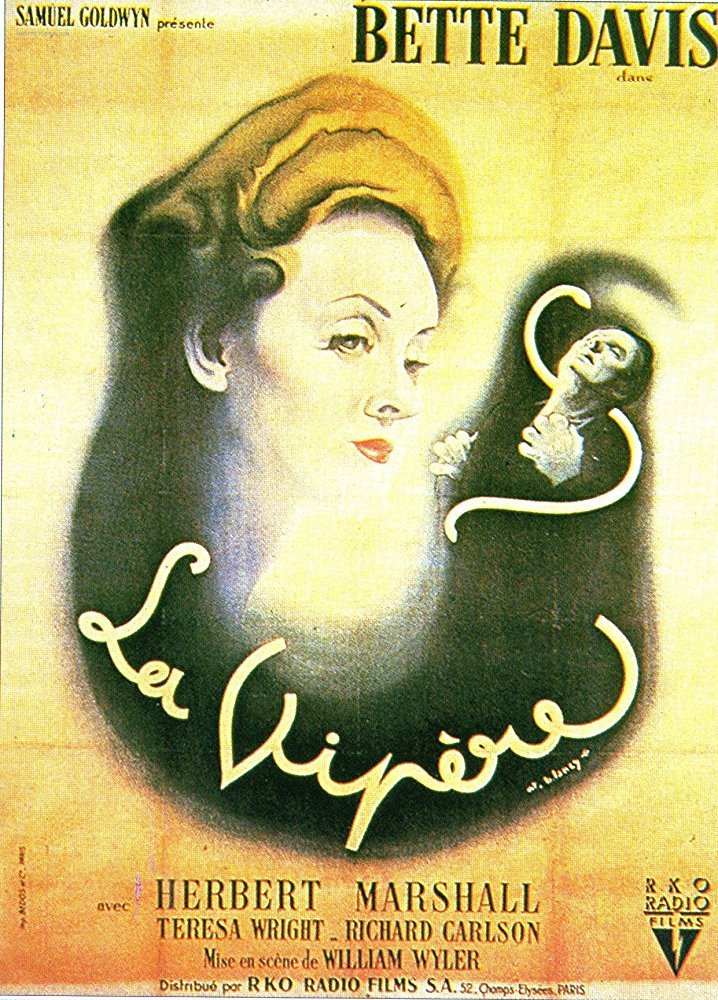

This costume was the most frequently featured in publicity photos, lobby cards, and film posters, despite it being the least historically accurate of Regina’s ensembles. Modern Screen attempted to vouch for its authenticity by focusing on the undergarments used to create the garment’s silhouette, stating, “For stays, designers had no whalebone, used steel instead” (“On Set with The Little Foxes” 8). In an attempt to historicize the costume, the writer of the article neglects to realize that steel had been in use for decades at the time in which the film was set. In addition, such a corset would not have been worn without a chemise. The desire to impose the impression of authenticity through corsetry was negated by the very design of the strapless gown, under which a chemise could not be worn. In designing this costume, Orry-Kelly may have referred to images of famed turn-of-the-century actresses like Camille Clifford, who was often featured on postcards wearing dresses with dangerously skimpy straps (fig. 34). Such revealing garments were associated with women of the theatre and other disreputable occupations. A woman of Regina’s social class would more likely be seen in an elegant black evening dress like the one in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection dating to 1898-1900, designed by the House of Worth (fig. 35). It has similar features to the dress worn by Bette Davis, especially in the uniquely decorated neckline, which mirrors the jagged edges of the beaded jet appliques at Regina’s décolletage. Another source of inspiration for this costume could have been a 1903 portrait by Italian painter Giovanni Boldini (fig. 36). The subject, Mademoiselle de Nemidoff, is dynamically rendered in a sweeping black evening gown, as if in mid-motion. Her flimsy sleeves have fallen from the crest of her shoulders and almost resemble a sheer shawl tucked around her upper arms. Her hairstyle and posture contribute to her likeness to Bette Davis as Regina Giddens, and it seems likely that both actress and costume designer referred to this well-known painting in the making of the film. Ultimately, this contentious costume served to create stylistic appeal for the audiences of the 1940s. It proved a close relative to the slinky strapless evening gowns worn by stars of the studio era, and it was easy for the film’s promoters to brand Bette Davis as a sort of femme fatale of yore (fig. 37). Many of the promotional posters used graphic features commonly associated with the film noir genre—abstracting the Regina’s historical signifiers with dramatic shadows and simplified, painterly linework (fig. 38). Such imagery increased the character’s potency, as if to suggest that her viciousness transcended the time period of the film’s setting and proved just as threatening in the present day.

Fig. 34 - Unknown. Postcard featuring Camille Clifford, ca. 1900. Private Collection. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 35 - House of Worth (French, 1858-1956). Evening dress, ca. 1899. Silk, cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.258.4a, b. Gift of Miss Eva Drexel Dahlgren, 1976. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 36 - Giovanni Boldini (Italian, 1842-1931). Mademoiselle de Nemidoff, 1903. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Source: Wikipedia

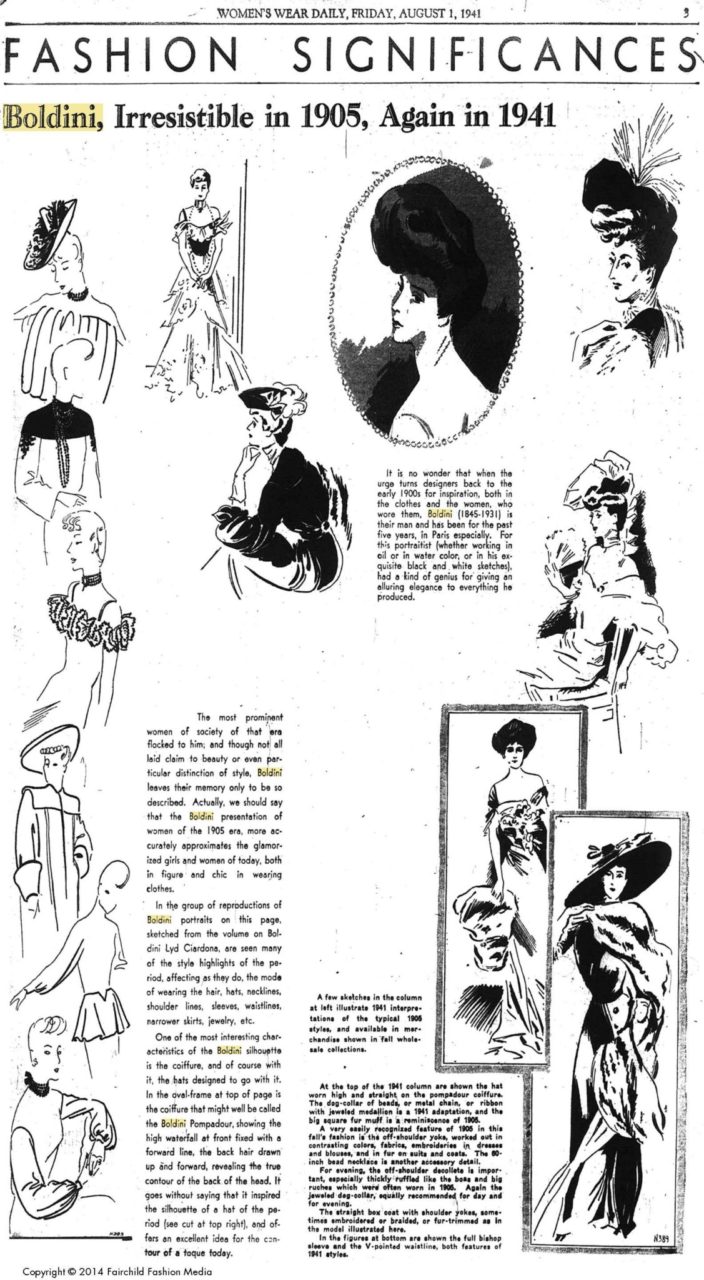

Influence on Fashion

A few weeks before the official premiere of The Little Foxes, turn-of-the-century influences on contemporary fashion were already prevalent. The August 1, 1941 issue of Women’s Wear Daily cited Boldini’s paintings as the source of inspiration (fig. 39). The article states, “We should say that the Boldini presentation of women of the 1905 era, more accurately approximates the glamorized girls and women of today, both in figure and chic in wearing clothes,” and then goes on to illustrate “1941 interpretations of the typical 1905 styles…available in merchandise shown in fall wholesale collections” (“Fashion Significances” 3). Design features commonly associated with the fashions from the turn-of-the-century—such as “off-shoulder lines, high collars, and heavy laces”—appeared on garments sold at American department stores that season (“Early 1900 Styles in Star Movies” 3). More editorials followed after The Little Foxes premiered, and for a time Regina Giddens became a sort of muse for fashion journalists, who reported on her period costumes as if they were phenomenons of present-day fashion. Such headlines appeared in Women’s Wear Daily: “Rounded Shoulders and Narrow Waistlines, Peplums and Low Flounces, as Worn by Bette Davis” (“Fashions Worn in the New Films” 3). This journalism forged a kinship between the clothes worn in the period film and those available for purchase to contemporary audiences. Millinery trends in the early 1940s also lent themselves to the turn-of-the-century influences, when ostentatious hats were commonly used to accessorize utilitarian fashions that would come during wartime. Some especially flamboyant designs harkened back to the early 1900s, with the use of fake taxidermied birds (fig. 40).

Fig. 39 - "Fashion Significances: Boldini, Irresistible in 1905, Again in 1941". Women's Wear Daily, August 1, 1941. Source: Fairchild Fashion Media

Fig. 40 - Designer unknown (American). Hat, 1945. Wool felt. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, C.I.53.70.4. Gift of Virginia Pope, 1953. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fig. 41 - Unknown. Bette Davis as the ugly-duckling-turned-swan Charlotte Vale in Now, Voyager, 1942. Warner Brothers Studios. Source: In the Good Old Days of Classic Hollywood

Fig. 42 - Unknown. Bette Davis does a screen test for Now Voyager, 1942. Warner Brothers Studios. Source: IMDb

Lingering traces of The Little Foxes were seen in Bette Davis’ next picture, Now, Voyager (1942). Another collaboration with Orry-Kelly, this film gave birth to one of Bette Davis’ more iconic roles—this time as a contemporary woman of fashion. Now, Voyager is the ultimate makeover story, in which costumes play a vital role. Soon after her dramatic transformation, Bette Davis’ character appears in a fashionable wide-brimmed hat, trimmed with micro-pleated tulle. The tall, conical crown recalls the shape of Regina’s picture hat at the end of The Little Foxes—this time, sans bird (fig. 41). Her hair, too, is borrowed from the turn-of-the-century, in a pompadour-inspired updo with Marcel waves in front (fig. 42). Following the premiere of The Little Foxes, it was noted that “Miss Davis’ coiffure is easily recognizable as the prototype of the pompadour coiffure of today with an increasing number of girls and women are adopting” (“Boldini Type Clothes” 26). However, the pompadour had already been established as a fashionable hairstyle at the beginning of 1941, and its popularity was likely unrelated to the success of The Little Foxes. Harper’s Bazaar reported in February of 1941 that “pompadours seem to be here to stay—and pompadours that mean business, not those timid afterthoughts that soon flatten into ordinary bangs” (Neff 119). Indeed, there was nothing timid about Bette Davis or her hair in The Little Foxes, making her portrayal of Regina Giddens one of film history’s favorite memories.

Conclusion

As a source for fashion studies, The Little Foxes holds up better than most other films produced in the 1940s and set at the turn-of-the-century—many of which were highly stylized movie musicals. Almost all of the costumes throughout the film adhere to the reigning principles of fashionable dress in the early twentieth century, and the film is more or less an accurate portrayal of the Southern aristocracy in 1900. The few historical anachronisms lie in some of Bette Davis’ costumes, which bear the distinctive flavor of glamour that permeates all aspects of Hollywood design. Consistent with other period films produced in this era, The Little Foxes demands less historical accuracy from its leading performer than it does from its supporting characters. At the height of the studio system, stars were beholden to the personas crafted by the studios’ publicity departments, and were therefore not free to lose themselves in outdated period dress, which could risk lessening their contemporary appeal. This film was ultimately produced as a star vehicle for Bette Davis—and as the so-called First Lady of Hollywood, she was obligated to deliver glamour to her fans in this role (fig. 43).

Fig. 43 - George Hurrell (American, 1904-1992). Bette Davis as Regina Giddens in a publicity photograph for The Little Foxes, 1941. Costume Design by Orry-Kelly. Source: IMDb

References:

- “AFI Catalog of Feature Films – The Little Foxes (1941).” The American Film Institute. https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/moviedetails/27019

- “Back Again…Leads Again! Samuel Goldwyn returns to production with the finest and greatest production of his memorable career!” Variety, Aug. 27, 1941, pp. 14-15.

- “Bette Davis.” Modern Screen, August 1941, p. 24.

- “Boldini Type Clothes Worn by Bette Davis in The Little Foxes.” Women’s Wear Daily, August 22, 1941, pp. 4, 26.

- Crowther, Bosley. “The Screen in Review: ‘The Little Foxes’ Full of Evil, Reaches the Screen of the Music Hall.” The New York Times, Aug. 22, 1941, p. 19.

- Davis, Bette. Mother Goddam. New York: Berkley Books, 1980. p. 157.

- “Early 1900s Styles in Star Movies Tie-In With Fall Merchandise.” Women’s Wear Daily, August 19, 1941, p. 3.

- “Fashion Significances: Boldini, Irresistible in 1905, Again in 1941.” Women’s Wear Daily, August 1, 1941, p. 3.

- “Fashions Worn in the New Films—Orry-Kelly’s 1903 Costumes for The Little Foxes Suggest 1941 Versions.” Women’s Wear Daily, August 13, 1941, p. 3.

- “Film Record Set by ‘Little Foxes.’” The New York Times, Aug, 23, 1941, p. 7.

- Hanna, David. Review of The Little Foxes, directed by William Wyler. Independent Exhibitors Film Bulletin. August 23, 1941, p. 6.

- Hamilton, James Shelley. Review of The Little Foxes, directed by William Wyler. National Board of Review Magazine. September 1941, pp. 4-5.

- Jorgensen, Jay and Donald L. Scoggins. Creating the Illusion: A Fashionable History of Hollywood Costume Designers. Philadelphia: Running Press Book Publishers, 2015.

- Landis, Deborah Nadoolman. Dressed: A Century of Hollywood Costume Design. New York: Harper Collins, 2007.

- Lester, Katherine Morris and Bess Viola Oerke. An illustrated history of those frills and furbelows of fashion which have come to be known as accessories of dress. Peoria, Illinois: Manual Arts Press 1940, p.530.

- Neff, Elinor Guthrie. “The Cosmetic Urge.” Harper’s Bazaar, February 1941, p. 119.

- “On Set with The Little Foxes.” Modern Screen, October 1941, pp. 8-10.

- Remington, Preston. Victorian and Edwardian Dresses. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications, 1939.

- Russell, Norton. “The Little Foxes.” Photoplay, Sept. 1941, pp. 44-45, 80-84.

- Women He’s Undressed. Directed by Gillian Armstrong, screenplay by Katherine Armstrong, Damien Parer Productions, 2015.

- York, Cal. “Inside Stuff.” Photoplay, Sept. 1941, pp. 6-8.