The Leopard (Ill Gattopardo) (1963)

Synopsis

The Prince of Salina, a noble aristocrat of impeccable integrity, tries to preserve his family and class amid the tumultuous social upheavals of 1860s Sicily.

Directed by

Luchino Visconti

Release date

27 March 1963 (Italy)

Costume Designer

Piero Tosi

Studio

- Twentieth Century – Fox (US)

- Titanus (Italy)

Source: IMDB

Film trailer

Introduction

Luchino Visconti’s (1906-1976) film, Il Gattopardo (1963), translated in the United States as The Leopard, is an Italian epic based on Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s (1896-1957) novel of the same name, published 1958. Both film and novel recount the decline of a Sicilian prince and his family during Italy’s Risorgimeno, when the middle class rebelled against the aristocracy to establish a democratic Italy. Lampedusa, a Sicilian aristocrat himself, based the character of Don Fabrizio, Prince of Salina on his own noble great-grandfather, who lived during the conflict and witnessed the downfall of his feudal family (Kael 2011, 723). In Visconti’s adaptation, the Prince is played by Burt Lancaster, alongside Alain Delon as Tancredi Falconeri, the prince’s nephew, and Claudia Cardinale as Angelica, Tancredi’s fiancé. In this paper I will describe and analyze the costumes of the Prince, Tancredi and Angelica, as well as some supporting characters, specifically in the opening scene and in the ball scene. All analysis is based on the 185-minute cut of the film on the Criterion Collection DVD set released in 2004 by Twentieth-Century Fox. The film is set in 1860 Sicily and focuses on a noble family whose lives will inevitably change due to the social upheaval that is taking place all around them. The filmmakers had to communicate through clothes and setting that the family was aristocratic while maintaining a certain level of historical accuracy. Since this paper will focus on two specific scenes, one taking place during the day and the other at night, it is important to establish what typical daywear and eveningwear for a European patrician family was in 1860.

Fig. 1 - Godey's Lady's Book. Fashion plate, Apriil 1861. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (Great Britain). Cage crinoline, 1860-1865. Spring steel, woven wool, linen, lined with cotton, and brass. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.150-1986. Given by Mrs. A. E. Valdez. Source: Victoria & Albert Museum

About the Period Setting

Women

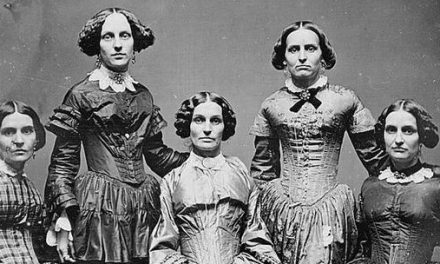

For women, the prevailing silhouette of the time was tightly corseted through the waist with a full, rounded skirt (Fig. 1). This broad based shape that resembled a bell was supported by cage crinolines (Fig. 2), which had replaced layers of petticoats as the way to maintain a skirt’s fullness. There was an emphasis on particular dress for different activities or public occasions, such as the walking dress, carriage dress and promenade dress. Daytime called for long sleeves, which may have been tight through the arms (Fig. 3) or constructed with more voluminous, pagoda-style sleeves. Bodices featured high neck lines with buttons up the center front and sloped shoulders. Fashions of the 1860s often featured masculine elements, especially evident in the bodices of the time period like the extant example from the Museum at FIT, which borrows military elements (Fig. 4). Lace was used for details like collars and cuffs. By the 1860s the invention of aniline dyes allowed for dresses to be dyed a much wider range of colors, allowing for brighter, more saturated hues. For day fabrics, cotton, wool and even silk would be used. Social rules demanded that women cover their heads with bonnets or other hats when outside and also served to protect from the sun. Bare shoulders were typical of 1860s evening gowns, with bodices featuring wide necklines and short sleeves. The volume in skirts remained full and emphasized a narrow waist. In some instances, dresses could transform from a day dress to an evening dress by using the same skirt and simply switching the bodice. Evening gowns of the period were often made of sumptuous materials that were reminiscent of the Rococo era. This is exemplified in Franz Xavier Winterhalter’s 1855 group portrait The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by Her Ladies in Waiting (Fig. 5), in which all the women are dressed in lavish evening dresses with the characteristic full skirts and off the shoulder bodices. One surviving example is made from similar materials as the garments seen in the painting, like silk taffeta, satin, tulle and other embellishments (Fig. 6). Fans were often necessary accessories at balls when dancers became over-heated. Eveningwear did not require a hat while inside, but hair would have been worn pulled back, parted down the center to the nape of the neck and with loops or ringlets covering the ears. Ornaments for eveningwear may have been floral wreaths, ostrich feathers or other decorations (V&A Museum 2017).

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (England). Afternoon dress, ca. 1860. Purple and black silk taffeta. New York: Museum at FIT, 2006.43.1. Museum purchase. Source: Museum at FIT

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (USA (possibly)). Afternoon dress, ca. 1865. Green silk faille, chenille, and velvet. New York: Museum at FIT, P88.43.1. Museum purchase. Source: Museum at FIT

Fig. 5 - Franz Xaver Winterhalter (German, 1805-1873). The Empress Eugenie Surrounded by her Ladies in Waiting, 1855. Oil on canvas; 300 x 420 cm (118.1 x 165.4 in). Compiègne: Musée du Second Empire, MMPO 941. Source: Wikimedia

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Scotland). Dress, ca. 1865. Cream silk taffeta, satin, tulle, cording and tassels and black silk ribbon. New York: Museum at FIT, 75.227.41. Gift of Mildred R. Mottahedeh. Source: Museum at FIT

Men

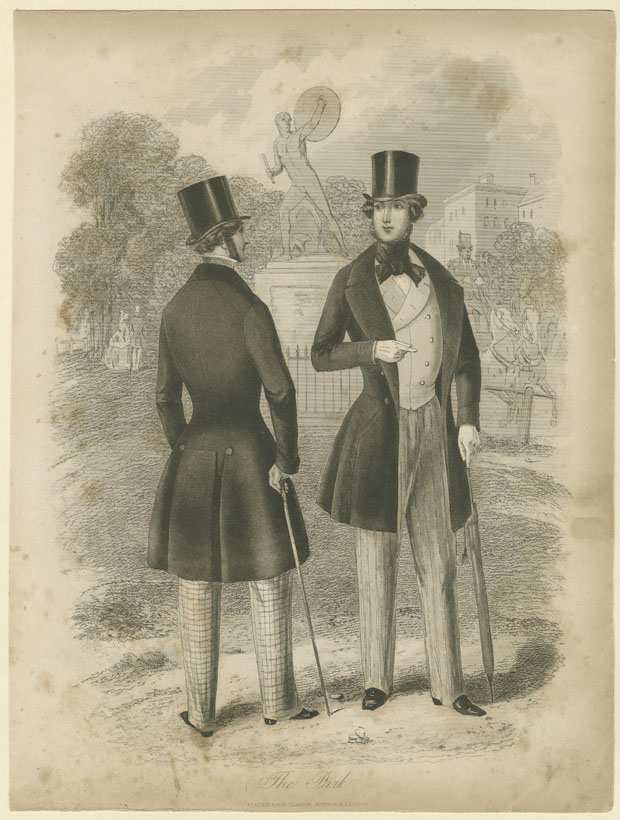

By the 1860s, fashion had established the three-piece suit as standard attire for men. Since all classes would don coats, waistcoats and trousers with ties or cravats (Perrot 1994, 33) (Fig. 7). Informal coats could be the knee-length frock coat, or the newer sack coat, a precursor to today’s suit jacket that was shorter cut to have a flat back. The 1860s saw a penchant for single-breasted and semi-fitted jackets and coats. Formal coats consisted of tails and were cut to emphasize a high, narrow waist. Waistcoats, with or without collars, allowed for some color and creativity in a man’s afternoon ensemble since it would be seen when a man wore his coat open, but this was only permissible during the day. In formal wear, the evening tailcoat, always black, would be paired with trousers the same color and material as the jacket, along with a white waistcoat. Hats were a necessary accessory to any well-dressed man, especially top hats, but would only be worn outside. Hair was worn natural, foregoing the wigs of the previous century. Longer sideburns were paired with a drooping moustache and, in some instances, a full beard (V&A Museum 2017).

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. The Park, ca. 1850-1860. Library of Birmingham, UK: R. Compton Rhodes Collection of Fashion Plates, F391 S623. Source: Library of Birmingham

Fig. 8 - James Tissot (French, 1836-1902). The Circle of the Rue Royale, 1868. Oil on canvas; 175 x 281 cm (68.9 x 110.6 in). Paris: Musée d’Orsay, RF 2011 53. Source: Wikimedia

A group portrait by James Tissot from 1868 (Fig. 8) exemplifies the decade’s men’s fashions in the same way Winterhalter’s painting does for the women. There were varying different cuts of the jackets and coats, but essentially the three-piece suit was a codified standard for nineteenth century men.

About the Costume Design

There are a large number of characters in the film, or at least extras, which allows viewers to evaluate a variety of costumes. The two scenes analyzed provide viewers with close-up and full-length views of the costumes, one taking place during the day and the other set at a formal ball.

Daytime

The ten minute opening scene shows the Prince and his family praying inside their large home and establishes the family as pious and aristocratic. Along with his wife and seven children, there are maids, a Jesuit priest and a number of other people in attendance. The camera pans across the group, all kneeling (Fig. 9). We see all the figures dressed in dark colors. The camera zooms in to the Prince’s wife who is dressed in a long sleeved black dress and a lace headdress. Her dress has a high neckline and buttons up the center front. Nearby are two men kneeling, both in dark suits, one in a grey waistcoat and the other in black. Their suits may have been made from wool. We get a glimpse of the Prince himself who is in a similar black jacket and waistcoat, kneeling near the priest wearing what looks like cassock.

Fig. 11 - 1964 The Leopard. . Source: Author

There is an interruption in the action of the story that causes the Prince to stand up, allowing the audience to see his full suit including grey trousers that contrast against his black coat (Fig. 10). Among the crowd, we can now see a maid in uniform wearing a black long sleeved dress with a high neckline with a white apron, an old woman wearing a typical day dress with a shawl and more young men in three-piece suits, usually of dark neutrals and a contrasting waistcoat. There is a shot of the Prince seated with his family all around him that allows us to see his wife and children’s costume (Fig. 11). In the foreground we see his daughter Concetta, who is in a long-sleeved, high-necked dress that buttons down the center front and has what appears to be black braided details. The skirt is full and round. Her sisters are wearing similar dresses in varying different neutral tones made of heavy looking fabrics, but with the braided details seen near the hem of the skirts. The sleeves and collars are a stark white against the dark colors of the dresses. The Prince’s sons are in their dull colored suits, one black and one brown, with crisp white shirts and neckties. The overall mood of all their appearances is heavy and stately. The last glimpse we have of the scene is the Prince’s wife fainting on a coach in a heavily decorated room, which allows us to see back views of her daughters’ dresses that have no extra embellishments.

Evening

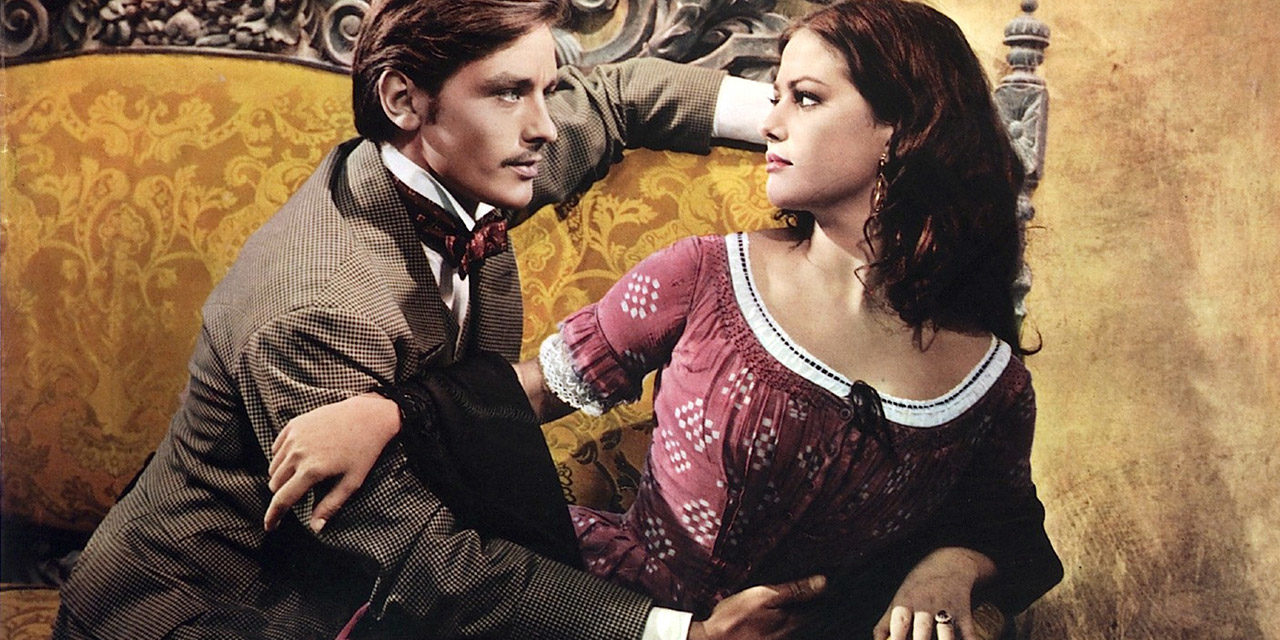

The film culminates in a ball scene that is approximately 50 minutes long. A huge crowd of people have shown up in their finest, women in their evening dresses and men in white tie. It’s a critical event for the Prince because his nephew is introducing his fiancé, Angelica, to society for the first time. Angelica wears an all white ball gown (Fig. 12) that looks to be made from an organza. Her bodice fits tightly through the waist and comes to a point in the center. The ruffled neckline reveals her shoulders and there is a bow at the center front. The skirt is round and voluminous with more ruffles as embellishments. Other women attendees of the ball are dressed in a very similar silhouette, in different colors and with varied accessories and other details. There is a shot of a group of women watching the Prince and Angelica when they dance (Fig. 13), which allows a clear view of the characters from the waist up. Each dress is a different color with varied trimmings, but essentially the same wide cut neckline and bare shoulders. Ruffles are featured along the neckline, as in Angelica’s dress. Each woman has accessorized for the occasion: fans, gloves, necklaces, floral wreaths for hair. When the camera allows for a complete shot of their ensembles the audience gets a complete sense of the silhouette and see how the fabrics behaved when in movement. Each woman’s hair is pulled back low behind the head and some women wear floral wreaths or other accessories.

Fig. 12 - 1964 publicity photo The Leopard. . Source: Pinterest

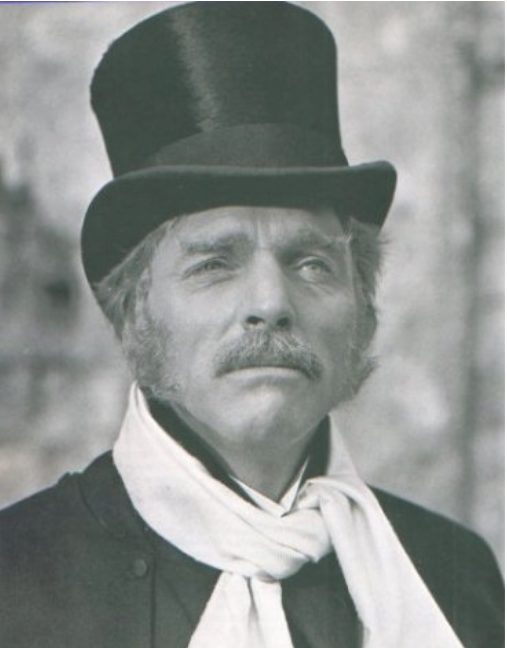

The men’s uniform for the ball consists of a black tailcoat, a white shirt, a white waistcoat and white tie (Fig. 14). Both men and women wear gloves throughout the ball. The men who are not in tails for the ball are in army uniforms. The suits and uniforms are most likely made from a heavy cloth like wool, which would allow the garments to maintain their tailored shape (Fig. 15). In the last shot of the party when the Prince is getting ready to leave, we see him put on a black overcoat, white scarf and black top hat (Fig. 16). Those who are wearing suits also don top hats to go outside and those in uniform complete their costumes with feathery regiment hats. The Prince’s hair is natural, parted off-center and worn with a drooping mustache and long sideburns. Tancredi is sporting a more youthful, slicked back hairstyle and thinner mustache. Men shown in the background all generally have short hair with either a mustache or long sideburns, sometimes both.

About the Costume Designers

Costume design is about working closely with the director” (Landis 2003, 148), The Leopard costume designer Piero Tosi (b. 1927) stated in an interview. He and the film’s director, Luchino Visconti, collaborated on a number of other films over a 25-year period, including Rocco and His Brothers (1960), Death in Venice (1971) and Ludwig (1973). The pair made a successful match thanks to their mutual dedication to representing authenticity on screen. Visconti got a reputation for being a “neo-realist” early in his career, which film critic David Thomson attributes to his use of filming in real locations and emphasizing human weakness and struggle (Thomson 2016,1075-1075). Soon after The Leopard was released, Vogue praised Visconti’s work by calling it, “The film in which his Renaissance taste for magnificent display, ornamentation and formal perfection fuses with his sensitivity to historical fact, with his historical compassion” (Moravia 1963, 298). Tosi has long been known for his commitment to historical accuracy. As a student of costume design, he stated that he “thought that production design should be approached in a different way, with more research and more authenticity, closer to the actual script and the nuances of the script’s ambience” (Landis 2003, 139). He recognized the difference between a fashion designer and a costume designer by saying, “A costume designer’s work is from story and culture, while the fashion designer captures trends that are in the air” (Landis 2003, 146).

For The Leopard, Tosi partnered with costumer Umberto Tirelli to construct the costumes. They began with researching old patterns and antique fabrics and created the costumes in a way that was more similar to “reconstruction rather than design” (Butchart 2016, 86). Replication was important since it would affect how an actor moved in the dress and therefore be more accurate. Foundation garments were important, unlike in so many other period films. Claudia Cardinale reportedly suffered from bruising caused by the corsets she wore during filming (IMDB 2017). Tosi’s goal when approaching a film is to maintain historical authenticity while also staying true to the script and the character. He said, “The study of a character may include a certain type of sleeve, a particular neckline, a tie, and a hairdo […] I try to get to know the actor or the actress, and then I begin to work from that image. I try to change a hairstyle, or the makeup, or the physical structure to bring the actor and character together” (Landis 2003, 142). For Cardinale’s character, Tosi attempted to make her look less sophisticated by putting grease in her hair to communicate Angelica’s lack of refinement (Landis 2003, 142). In The Leopard, the collaboration between Visconti and Tosi, as well as cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno, production designer Mario Garbuglia and many others resulted in a cohesive product. The use of candlelight in many of the film’s scenes compliments the way the costumes move. The film’s score by Nino Rota blends into the waltz that plays as the Prince and Angelica dance. Every detail was carefully considered, from furniture and decorations that were prepared in Sicily (Landis 2003, 140) to an embroidered handkerchief that Cardinale kept in her purse but never appeared on camera. The Palazzo Valguarnera Gangi in Sicily provided a grand backdrop to the climactic ball scene (IMDB 2017). All together, the film replicates a specific time and place, which came from Visconti’s family reminiscences. Tosi said, “It was a color film and the landscape was the background of the story. We adapted the colors of the costumes to the backgrounds that we chose” (Landis 2012, 448). Visconti and Tosi’s contributions to film have not gone unnoticed. Tosi received an Academy Honorary Award in 2013 for his contributions towards costume design (Oscars 2017). For The Leopard, Tosi was nominated for the 1963 Academy Award in costume design (IMDB 2017) while Visconti won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival the same year (Festival de Cannes 2017).

Historical Accuracy

The historical accuracy of the costumes in The Leopard is astounding. The film is often referred to as Tosi’s “masterpiece” (Landis 2012, 446) and it’s easy to see why. The design for Angelica’s ball gown was based in real material culture and can be compared to surviving garments that are now in museum collections. In silhouette, the gowns worn by other characters at the ball emulate fashion plates of the period, down to exact details like gloves and other accessories that the nineteenth century dictated. The men’s costumes are also very true to the period, as we can see in fashion plates of the time. There was great attention paid to the smallest social requirements that dictated the nineteenth century, like the culture of hats and gloves, both which would have been required. There is some level of interpretation coming from Tosi, based on his insistence that the costumes must reinforce each character. But even with this, he never strays far from historical precedents. In fact, in terms of costume authenticity, the film accomplishes the rare feat of getting much more correct than it does wrong.

One of the most obvious elements of contemporary fashion in the film is Cardinale’s use of winged eyeliner. She is the only woman who wears makeup in the film, which sets her apart from the other women, especially those in the Prince’s family. Also, it may be a way to communicate her character as a symbol of the new Italy that was forming. This is also shown at the ball in the way her white dress stands out in a room full of women in equally huge ball gowns. The recently invented aniline dyes allowed for bright colors, which can be seen on the background actors, but by putting Angelica in white and allowing her to be relatively unadorned when it comes to accessories, she is symbolizing both her upcoming marriage and a new start for Italy. Comparatively, the Prince’s wife is dressed in a heavily adorned black evening gown that is reminiscent of the huge, stately manor where she and her family live. She acts as a symbol of the Italy that is being left behind.

The Prince himself is an embodiment of the decline of nobility. He is always elegant, in his mannerisms, dress and demeanor. Scenes showing him dancing allow viewers to get a 360 degree view of his suit, which show how his costume and his posture seem unified. The opening scene of the family praying shows everyone in dark, somber colors. They all give off an air of piety, especially the Prince’s wife, whose lace headdress gives the indication that she is the most devout of them all. Even the other members of the household exemplify this idea, by adhering to the image of a conservative, noble family. This adds to the theme of the aristocracy being outdated.

Influence on Fashion

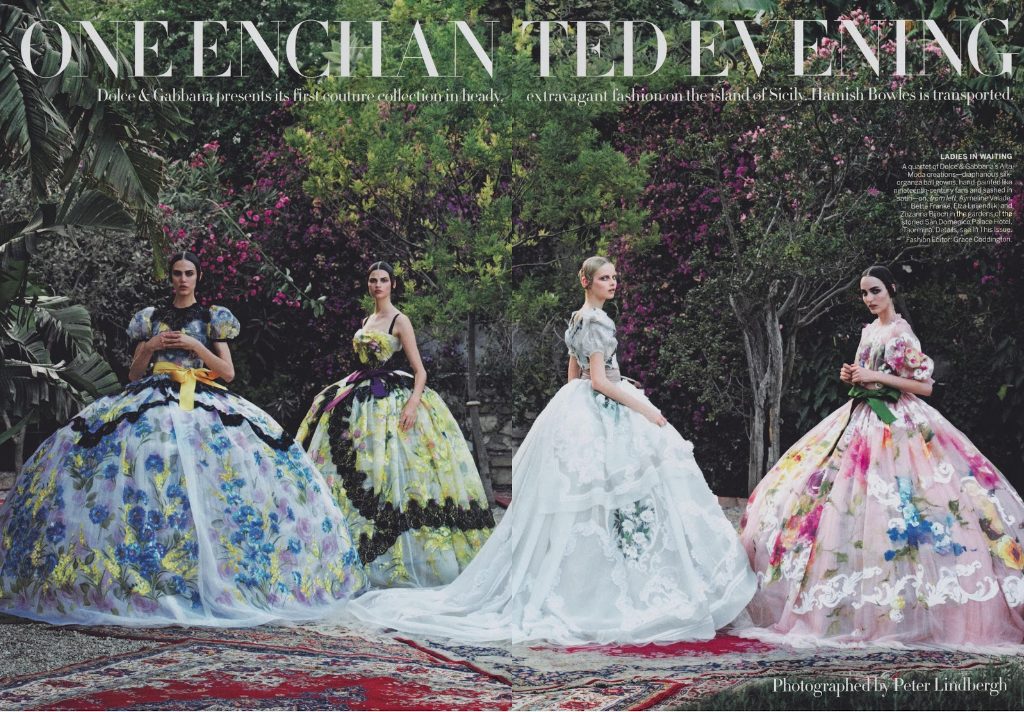

The Leopard has captured the imagination of a number of designers, especially Italian ones. Most notably, Dolce & Gabbana have used Tosi’s designs as a reference point, numerous times. In their Autumn/Winter 2012-2013 collection (Fig. 17) they emulate the full, rounded skirt shape. More recently, in their Alta Moda 2017 collection the opening dress of the show alludes to the quote, “everything needs to change, so that everything can stay the same” (Leitch 2017). The quote was taken from a line in both the novel and the film and was handpainted along the hem of a skirt (Fig. 18) that prominently features a leopard as a direct reference to the Prince. Also drawing from this quote, Roberto Cavalli also cited the film as inspiration for his Autumn/Winter 2008-2009 ad campaign. He said that the notion that “the more things change, the more they stay the same” is a metaphor applicable to fashion (Butchart 2016, 88).

Fig. 18 - Dolce & Gabbana (Italian). Gown, Alta Moda 2017. Source: Vogue.com

Fig. 17 - Peter Lindbergh (Photo). Gowns from Dolce & Gabbana’s Autumn/Winter 2012-13 collection, as seen in Vogue, September 1, 2012. Source: Vogue

Conclusion

This film would be of interest to both fashion historians and costume designers because of its impressive accuracy. It shows very little contemporary influence and can give those interested in historical fashion an accurate view of what would have been worn in 1860. Costume designers should also look to Tosi as a successful costume designer to emulate when approaching period fashion. It will enhance anyone’s knowledge about the period in the way the costume are married to the set and art design.

References:

- Butchart, Amber. The Fashion of Film: How Cinema has Inspired Fashion. London: Hachette, 2016.

- Festival de Cannes. “Il Gattopardo.” Accessed October 8, 2017. http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/films/il-gattopardo

- IMDB.com. “The Leopard.” Accessed October 9, 2017. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0057091/

- Kael, Pauline. “A Masterpiece.” In The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael, edited by Sanford Schwartz, 723-729. New York: Library of America, 2011.

- Landis, Deborah Nadoolman. Costume Design. Burlington, MA: Focal Press, 2003.

- ______. Hollywood Sketchbook: A Century of Costume Illustration. New York: Harper Design, 2012.

- Leitch, Luke. “Sicilians Do It Better: Dolce & Gabbana Present Their Alta Moda in Palermo.” Vogue.com, posted July 8, 2017. https://www.vogue.com/article/dolce-and-gabanna-alta-moda-palermo

- Moravia, Alberto. “Visconti, The Leopard Man.” Vogue, July 1, 1963.

- Oscars.org. “2013 Governor’s Awards.” Accessed October 8, 2017. https://www.oscars.org/awards/governors/2013/index.html

- Perrot, Philippe. Fashioning the Bourgeoisie: A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century. Translated by Richard Bienvenu. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Thomson, David. The New Biographical Dictionary of Film. New York: Knopf, 2016.

- Victoria & Albert Museum. “History of Fashion, 1840-1900.” Accessed October 7, 2017. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/h/history-of-fashion-1840-1900/