Princess Diana’s wedding dress, made by the Emanuel Salon, combines historical inspirations and a fairytale look with strict royal tradition. Its influence on the bridal world can still be seen today.

About the Look

Diana Frances Spencer (1961-1997), Princess of Wales, walked down the aisle on July 29th, 1981 in an ivory silk taffeta gown embellished with antique lace once owned by Queen Mary (1867-1953) (Fig. 1). The dress featured thousands of hand-embroidered sequins and pearls; some were arranged in a heart motif on the fitted, boned bodice, while others decorated the waist, hem, and long train (Dunn). The silhouette of the dress included a Romantic-style full skirt and large puffed sleeves with lace flounces on the neckline and cuffs (Fig. 2).

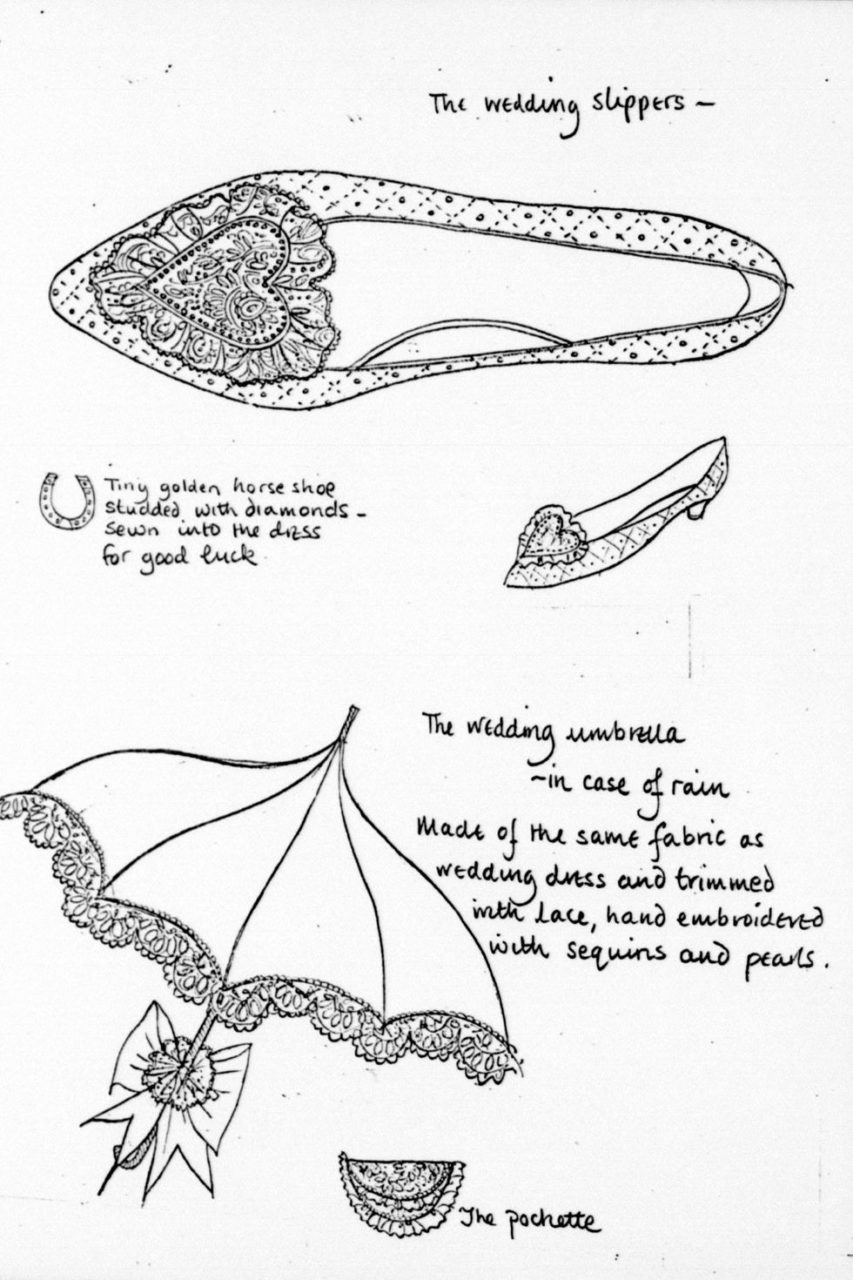

The ivory silk tulle veil featured mother-of-pearl sequins, held in place with a diamond tiara owned by the Spencer family (Dunn). Not clearly visible under Princess Diana’s wedding dress were hand-made ivory silk slippers (Fig. 3) adorned with 542 sequins and 132 pearls that centered around another heart-shaped design (Chrisman-Campbell 176). The hand-painted arch soles bore the initials ‘C’ and ‘D’, for Charles and Diana, and featured a kitten heel. These incredibly detailed shoes took cobbler Clive Shilton about six months to create (Chrisman-Campbell 176). Princess Diana’s 25-foot train and cathedral-length veil were the longest train and veil ever worn at a royal wedding (Fig. 4). The Emanuels had designed a matching parasol in case of rainy weather (Fig. 5). Princess Diana carried a bouquet (Fig. 6) made of “gardenias, lilies-of-the-valley, white freesia, golden roses, white orchids, and stephanotis” down the aisle (Goodey).

Charles, Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer—her official title at the time—were married at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. Princess Diana was seen as the likely future queen consort and so the wedding commanded a considerable amount of attention from the public and the media. The marriage ceremony had a global televised viewership of an estimated 750 million people in 74 countries and some 600,000 spectators that lined the route from Buckingham Palace to St. Paul’s (BBC). Given the amount of attention the wedding received, the far-reaching influence of her wedding dress design seems to have been inevitable.

A September 1981 Harper’s and Queen article, “The Wedding of the Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer,” emphasized the fairy-tale character of the event and enthusiastically praised the overall look and effect, giving a good sense of the laudatory press coverage at the time:

“It has been a truly fairy-tale romance, with Lady Diana capturing the hearts of everyone who met her… There was more beautiful music at this wedding, than, I think, at any wedding that has ever taken place….” (222)

“She was the most beautiful bride anyone could dream of. Her wedding dress, designed as we all know by David and Elizabeth Emanuel, was made of ivory silk taffeta, and old lace hand embroidered with tiny mother of pearl sequins and pearls. The twenty-five foot train was edged with the same sparkling lace. Her veil, of ivory silk tulle, was also hand embroidered with thousands of mother of pearl sequins and was held in place by an exquisite Spencer family diamond tiara.” (224)

Fig. 1 - David and Elizabeth Emanuel (British). Princess Diana's wedding gown is displayed at a preview of the traveling "Diana: A Celebration" exhibit at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, October 1, 2009. Photo by William Thomas Cain. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 2 - David and Elizabeth Emanuel (British). Diana, Princess of Wales, on her wedding day, July 29, 1981. Photo by Lichfield Archive. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 3 - Clive Shilton (British). Princess Diana's wedding slippers are displayed at a preview of the traveling "Diana: A Celebration" exhibit, October 1, 2009. Photo by William Thomas Cain. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 4 - David and Elizabeth Emanuel (British). Diana Princess of Wales enters the church with her 25-foot train trailing behind her., July 29, 1981. Photo by Ron Bull. Source: The Star

Fig. 5 - David and Elizabeth Emanuel (British). Sketches of accessories which will be worn or carried by Lady Diana Spencer during her wedding to the Prince of Wales at St. Paul's Cathedral in London, July 29, 1981. Photo by PA Images. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 6 - David and Elizabeth Emanuel (British). Diana, Princess of Wales, wearing an Emanuel wedding dress, leaves St. Paul's Cathedral with Prince Charles, Prince of Wales at their wedding, July 29, 1981. Photograph by Anwar Hussein. Source: Getty Images

David Emanuel (Welsh, born 1952) and Elizabeth Emanuel (British, born 1953). Princess Diana’s Wedding Dress, 1981. Ivory silk taffeta and antique lace embroidered with pearls and sequins. Collection of Henry Mountbatten-Windsor. Source: Getty Images

About the context

Royal Tradition

The British royal family has a long history of creating fashionable trends that later have been adopted by the public—both domestically and internationally. But beyond setting new fashions, royal wedding dresses also must incorporate older traditions, reflecting a bride’s personal preferences while honoring royal precedents. Since Charles, Prince of Wales, was heir apparent to the throne, Princess Diana’s wedding dress was expected to reflect the heritage of the British royal family.

In the 19th century, Queen Victoria (1819-1901) had redefined royal wedding dress traditions (Fig. 7) [Read all about her 1840 wedding gown in our analysis essay!]. Victoria chose a white gown to distance herself from other royal brides who typically wore ostentatious gold-embroidered dresses with red velvet robes of state (Lee). Prior to Victoria’s 1840 wedding, everyday brides typically wore garments that were considered their Sunday best; this meant bridal attire came in a range of colors besides white, including “red, pink, blue, brown, or even black” (V&A – Wedding Colours). But Victoria’s choice of white established it as a favorite bridal color that is still dominant today.

Fig. 7 - Mary Bettans (English). Queen Victoria’s wedding dress, 1840. Spitalfields silk, honiton lace. London: The Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 71975. Source: Royal Collection Trust

Victoria also saw the dress as an opportunity to support Britain’s struggling Honiton lace-makers; the dress was made from “white satin with a deep flounce of Honiton lace” that was later removed and reused on another gown (Lee). Since then, the use of Honiton lace has become a key feature of British royal wedding dresses as has loyalty to British designers and producers. After Queen Victoria’s wedding, many brides emulated the monarch by wearing white wedding dresses adorned with lace, and her romantic young marriage to Prince Albert helped create the fairy-tale idea of the royal wedding still common today (V&A – Victoria Connection).

Fig. 8 - Photographer unknown (British). The wedding of Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh, November 20, 1947. Source: Getty Images

While not officially mandated, several other traditions also shape royal wedding dresses. Princess Elizabeth, now Queen Elizabeth II (born 1926), had long sleeves and a conservative neckline on her 1947 satin wedding dress designed by Norman Hartnell, which set the standard for modesty (Fig. 8). Since then, most British royal brides have followed her example. Elizabeth’s ivory silk wedding dress incorporated crystals and ten thousand seed pearls with “an iconographic scheme of national and Commonwealth floral emblems in gold and silver thread and pastel-coloured silks” (RCT).

Long trains have also been a signature of royal wedding dresses. Elizabeth’s dress featured a 15-foot long silk tulle “star-patterned train, woven in Braintree in Essex, inspired by the famous Renaissance painting of Primavera by Botticelli, symbolising rebirth and growth after the war” (RCT). Diana, as noted above, however, pushed this tradition even further with her own 25-foot train.

One of the most striking symbols of royal and aristocratic weddings is the diamond tiara. Icons of power and rank, the tiaras worn by royal brides are typically family heirlooms. Princess Elizabeth wore Queen Mary’s fringe tiara at her 1947 wedding. In 1973, Anne, Princess Royal, Elizabeth’s daughter, wore the same tiara at her wedding. To honor this tradition, Princess Diana wore a diamond tiara from the Spencer family’s collection.

About the Design

Princess Diana’s wedding dress was designed by the Emanuel Salon, which was headed by British designers David and Elizabeth Emanuel (Fig. 9). The Emanuels were inspired by the grandeur and rich heritage of the monarchy in their previous bridal designs. The Victoria & Albert Museum describes a 1979 Emanuel wedding dress in their collection (Fig. 10):

“With its festooned and trained crinoline- style skirt, and frills, bows, and fabric flowers, this romantic gown is a precursor of the Emanuels’ design for Lady Diana Spencer’s wedding dress in 1981. The Emanuels were inspired by Winterhalter’s portraits of the 1860s–the same source that prompted Norman Hartnell to revive full-skirted styles for the Queen Mother in 1938.”

Fig. 9 - Tim Graham (British, born 1948). Fashion designers David Emanuel and Elizabeth Emanuel in their workshop in Mayfair, May 1981. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 10 - David and Elizabeth Emanuel (British). Wedding dress, 1979. Ivory silk taffeta dress with pink ribbon bows. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.181-1980. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 11 - Franz Xavier Winterhalter (German, 1805–1873). Wiencyzyslawa Barczewksa, Madame de Jurjewicz, 1860. Oil on canvas; 156.1 x 124 cm (61 7/16 x 48 13/16 in). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1998.396. Source: MFA

Fig. 12 - Sir Gerald Kelly (British, 1879-1972). Queen Elizabeth, Queen Mother, in a dress designed by Norman Hartnell, 1938. Oil on canvas; 98.4 x 78.1 cm (38 3/4 x 30 3/4 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4962. Source: NPG

German artist Franz Xavier Winterhalter was a master of painting 19th-century aristocratic portraits, with close attention to fabrics and fashion details such as bows, ribbons, and lace, as can be seen in his 1860 portrait of Wiencyzslawa Barczewka, Madame de Jurjewicz (Fig. 11). Norman Hartnell’s dress for Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother (Fig. 12), shows a similar enthusiam for large crinolined skirts; the Emanuel’s 1979 wedding dress (Fig. 10) shares the same flounced decoration on the skirt.

Making Diana’s wedding dress was the commission of a lifetime, but it was especially important for the Emanuels as they were relatively unknown when they received the commission. Designing a royal wedding dress was a challenge that placed intense pressure on them, especially because they had to keep in mind royal traditions alongside Princess Diana’s wishes.

In an interview with BBC Designed, Elizabeth Emanuel explained their approach:

“We just went for drama… It was everyone’s idea of a fairy princess. The time was perfect for that. It was a time of frills and flounces.” (Baker)

Diana added personal touches to the dress by considering the old adage for brides: something old, something new, something borrowed, and something blue. She incorporated antique Carrickmacross lace from Queen Mary, the new dress designed by the Emanuels, her family’s Spencer tiara, and a small blue bow sewn into the waist of her dress (Lang).

There was great public interest surrounding the design of the dress. The media had long had a reputation for invading the privacy of the royals, and strict measures were put into place to ensure secrecy. They installed heavy window blinds and stored their sketches (Fig. 13) and fabric swatches in a safe (Vargas). The final design was successfully kept a secret until the day of the wedding. An article published the day after the wedding dubbed Diana’s wedding dress the “most closely guarded secret in fashion history” (Johnson).

The Emanuel’s design was thoroughly historical in its inspiration. The bold silhouette with its puffed sleeves and pronounced shoulders emphasized Diana’s waist, which was further set off by the large crinolined skirt. The gigot sleeves and ruffled neckline look like they came straight out of a gown from 1895 (Fig. 14). Additionally, the full romantic skirt speaks not only to the styles of the 1950s, heralded by Christian Dior’s 1947 New Look, but especially to the crinoline silhouette of the 1860s (Fig. 15), painted by Winterhalter (Fig. 11). The dress itself was supported by layers of tulle that helped to retain the voluminous shape. The pronounced shoulders, inspired not only by the excess of the 1890s but also the self-sufficiency of the 1940s, became a major trademark of 80s fashion as women turned to power-dressing.

In the 1980s, fashion had entered a postmodern era that drew inspiration from an eclectic array of historical fashion styles and global trends. While large puffed sleeves and full skirts had been seen earlier–as in Valentino’s 1980 white couture dress worn by Beverly Johnson (Fig. 16)–Princess Diana and her wedding gown were crucial in defining the newest fashionable silhouette. Replicas of the dress and designs inspired by it flooded the market; the Emanuels’ wedding design became a “massive trend in bridal wear,” primarily for their use of tulle and ruffles—a different direction than the “more conventional, stiff, A-line creations” of the 1950s (Baker). This bridal trend extended to formal and evening dresses which began to feature similar puffed sleeves, tapered waists, and voluminous skirts.

In 1981, the Emanuel wedding dress for Diana cost an estimated $115,000 (compared to a regular Emanuel wedding dress with a starting cost of $5,610) (Vargas). In a 2005 interview with CBS News, Elizabeth Emanuel revealed that a duplicate version of Diana’s dress was created as a backup and was later displayed at Madame Tussauds [See the Afterlife section below] (CBS News). But a second wedding dress with a different design was also created–one that did not feature the enormous gigot sleeves–in the event the initial dress design was leaked to the press (Gonzales).

Fig. 13 - David and Elizabeth Emanuel (British). A sketch of Lady Diana's wedding dress, 1981. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 14 - Lafayette Ltd (British, founded 1880). Lady Beatrice Frances Elizabeth Pole-Carew (née Butler), ca. 1893-5. Cabinet card; 15.3 x 10.4 cm (6 in x 4 1/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG x36207. Purchased 1991. Source: NPG

Fig. 15 - Photographer unknown. Hand coloured photograph of Princess Louis of Hesse and by Rhine standing at an altar in her wedding dress, 1862. Hand-coloured photograph, probably albumen; 18 x 13 cm. London: Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 2374616. Source: The Royal Household

Fig. 16 - Valentino Garavani (Italian, 1932-present). Beverly Johnson in Valentino Couture, 1980. Photo Mike Reinhardt. Source: Valentino

Its Afterlife

The success of Princess Diana’s wedding dress lent the Emanuel Salon prestige and popularity, especially because they continued to create more garments for Diana(Figs. 17-18) and other members of the royal family. Yet, the wedding dress of Princess Diana remains their most notable design (Melik).

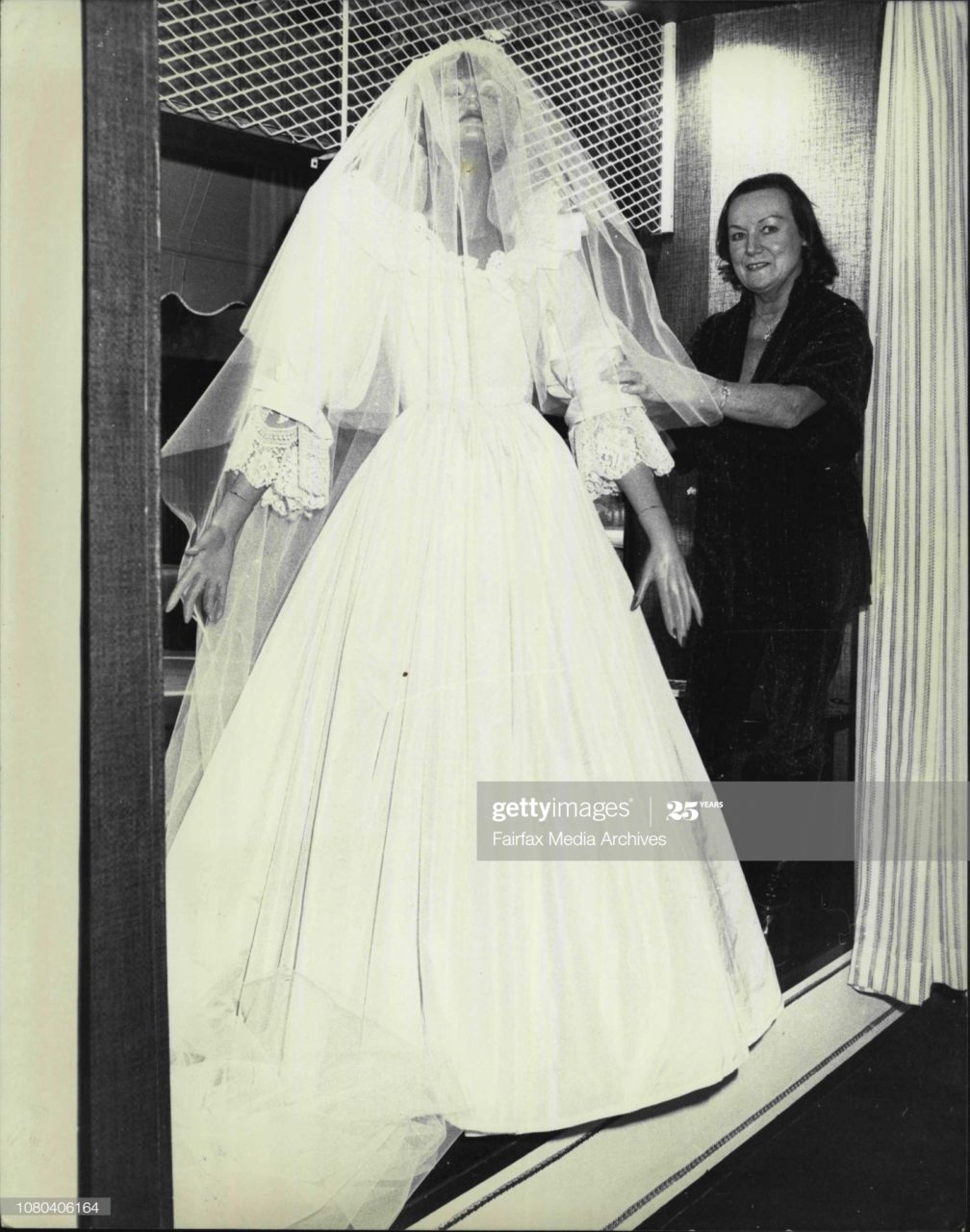

Following the royal wedding, a duplicate version of the dress went on display at Madame Tussauds (Fig. 19) (Gonzales). To this day, the Emanuel brands receive requests from clients to create replicas of the iconic wedding dress.

Fig. 17 - Tim Graham (British, born 1948). Prince Charles Dancing With His Wife, Princess Diana, In Melbourne, During Their Official Tour Of Australia. The Princess Is Wearing A Diamond And Emerald Choker (a Wedding Gift From The Queen) As A Headband With A One-shouldered Turquoise Satin Organza dress Designed By David And Elizabeth Emanuel, October 1, 1985. Source: Getty

Fig. 18 - Photographer unknown. Diana, Princess of Wales attends the premiere of the James Bond film 'The Living Daylights' in London wearing an Emanuel dress, June 1987. Hulton Royals Collection. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 19 - Michael Crabtree. The wax work model of Diana, Princess of Wales at London's famous tourist attraction Madame Tussauds, February 2000. Source: Getty Images

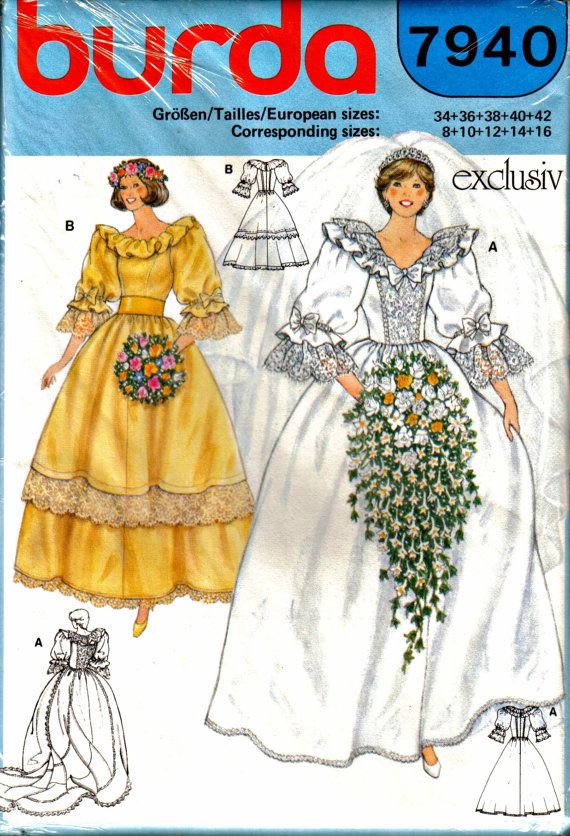

Hours after the wedding took place, replicas surfaced with manufacturers rushing to recreate the iconic wedding dress for as low as $467 (Fig. 20) (Johnson). Sewing pattern brands like McCalls and Burda also quickly issued replica patterns (Fig. 21).

After Diana’s unexpected death on August 31, 1997, an exhibition titled “Diana: A Celebration” was created to display a hundred and fifty artifacts from her life (Fig. 22) including her tiaras, designer gowns and suits, family heirlooms, letters, paintings, and videos. Her wedding ensemble was among the garments featured in the exhibition (“Sad End of Diana Exhibit at Althorp: Packing for America”). Initially opening in July 1998 at the Spencer’s Althorp estate, where Princess Diana spent part of her childhood, the exhibition finally closed in August 2014. Proceeds of more than £1.2 million were donated to the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Fund which funds charities she had previously supported (“Princess Diana: Althorp House Exhibition to Close”).

Fig. 20 - Paul Murray. Boutique owner and designer Miss Brown of double bay with her replica of the wedding dress worn by the Princess of Wales, Lady Diana Spencer, August 3, 1981. Fairfax Media Archive. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 21 - Burda. Lady Diana's Wedding Gown dress Sewing Pattern, circa 1981. Source: Etsy

Fig. 22 - Tana Weingartner. Princess Diana exhibit makes final stop in Cincinnati, February 2014. Cincinnati: Cincinnati Museum Center. Source: WVXU

Princess Diana’s wedding dress is one of the most recognizable garments of the 20th century and is also considered to be one of the most iconic wedding dresses of the century. In 2007, bridal retailers were still calling Diana’s dress the “gold standard,” emphasizing its lasting influence “long–long–after the dress itself went out of style” (Nixon-Knight). Elements of her wedding dress design remain popular in bridal fashion today, as some brides inevitably chase that fairytale dream.

References:

- Baker, Lindsay. “Culture – The Dress That Made the World Gasp.” BBC Designed, 29 Apr. 2019, BBC.

- BBC. “The Wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer.” Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/anniversaries/july/wedding-of-prince-charles-and-lady-diana-spencer.

- Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. Worn on This Day: The Clothes That Made History. 2019. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1128055494

- “Di’s Backup Bridal Gown In Dispute.” CBS News. Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/dis-backup-bridal-gown-in-dispute/.

- Dunn, Charlotte. “Royal Wedding Dresses throughout History.” The Royal Family, 28 Feb. 2019, https://www.royal.uk/wedding-dresses

- Gonzales, Erica. “Princess Diana Had a Second Wedding Dress That She Never Even Saw.” Harper’s Bazaar, 17 Aug. 2018, www.harpersbazaar.com/celebrity/latest/a22756759/princess-diana-second-wedding-dress/.

- Goodey, Emma. “Diana, Princess of Wales.” The Royal Family, 31 Mar. 2020, www.royal.uk/Diana-princess-wales.

- Jennifer. “The Wedding of the Prince of Wales and Lady Diana Spencer.” Harpers and Queen, Sept 1981, 222-225. Retrieved from https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2818/docview/2020139719?accountid=27253

- Johnson, Maureen. “Design of Lady Diana’s Wedding Dress Revealed.” The Press-Courier, 30 July 1981, pp. 11, https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=BjtLAAAAIBAJ&sjid=OCINAAAAIBAJ&dq=dianawedding&pg=2406,7438391.

- Lang, Cady. “Best British Royal Wedding Dresses in History: Photos.” Time, Time, 1 May 2018, Time.

- Lee, Summer. “1840 – Queen Victoria’s Wedding Dress.” Fashion History Timeline, 28 Jan 2020. Accessed 14 July 2020. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1840-queen-victorias-wedding-dress/

- Melik, James. “Royal wedding: Diana’s designers on how the dream faded.” BBC World Service, 16 Feb. 2011, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-12269667

- Nixon-Knight, Lynnell. “Natural Evolution: How the Modern Wedding Dress Came to Be.” Indianapolis Monthly. Jan. 2007, Google Books.

- “Princess Diana: Althorp House Exhibition to Close.” BBC News, BBC, 11 May 2013, BBC.

- “The Queen’s Wedding and Coronation Dresses to Be Displayed Together for the First Time to Mark Her Majesty’s 90th Birthday.” Royal Collection Trust, Royal Collection Trust, 27 May 2016, Royal Collection Trust.

- “Sad End of Diana Exhibit at Althorp: Packing for America.” Royal Central, 6 Sept. 2013, Royal Central.

- Vargas, Chanel. “Every Detail About Princess Diana’s Iconic Wedding Dress.” Town & Country, Town & Country, 11 Apr. 2018, www.townandcountrymag.com/the-scene/weddings/g18205746/princess-diana-wedding-dress/.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “V&A · The Victoria Connection.” Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-victoria-connection.

- Victoria and Albert Museum. “V&A · Wedding Colour.” Accessed July 15, 2020. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/wedding-colour.