Vivienne Westwood’s 1990 corset from her “Portrait Collection” took an 18th-century painting and garment type and updated them to the 20th century. She emphasized the erotic power of the form, but employed more modern, flexible materials to improve comfort.

About the Look

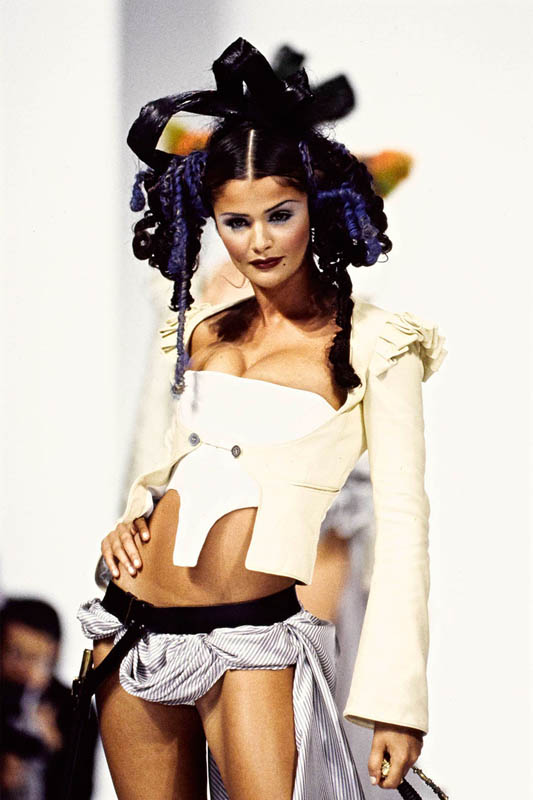

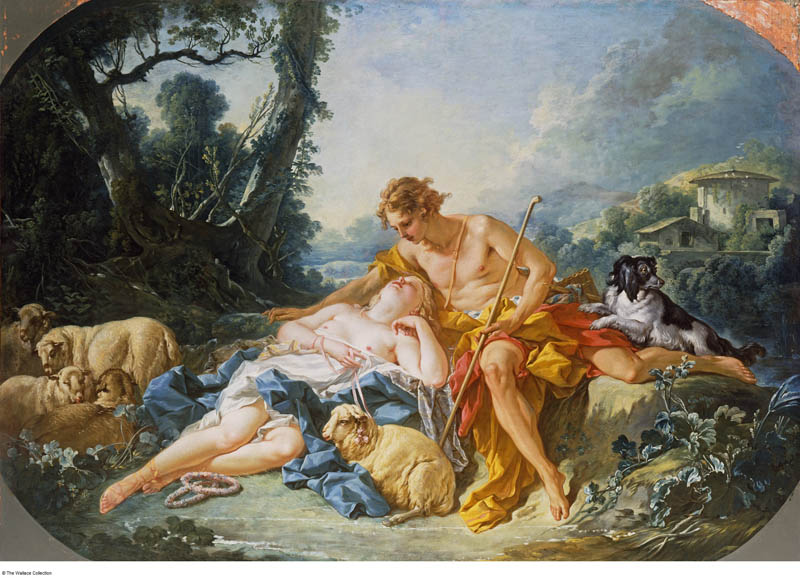

Vivienne Westwood is known for her reinterpretations of past fashions, subverting their purpose and bringing them into the current era. This corset (Fig. 1), which debuted in her 1990 Spring/Summer Portrait Collection, was no exception. On the front panel of the corset, Westwood printed the 1743 painting Daphnis and Chloe, Shepherd Watching a Sleeping Shepherdess by French Rococo artist François Boucher (Fig. 9). It is framed by shoulder straps featuring classical motifs and gold sides.

The corset emulates the corset shape from the eighteenth century (Fig. 2), however, the fabrics used to create it have been modernised. Westwood utilises more comfortable and flexible fabrics, such as lycra, and leaves out the traditional boning which is used in corsetry to maintain a rigid structure and shape. Furthermore, Westwood has alternatively presented her corset as outerwear instead of an undergarment. By utilising the corset as outerwear, Westwood subverts the traditional purpose of corsetry and in turn, reclaims it as a symbol of female liberation and empowerment.

Fig. 1 - Vivienne Westwood (British, 1941-). Corset, 1990. Polyamide, polyester, lycra. London: Victoria & Albert Museum. T.216-2002. Source: V&A

Vivienne Westwood (Italian, born 1940). Vivienne Westwood (British, 1941-). Corset, 1990. Polyamide, polyester, lycra. London: Victoria & Albert Museum. T.216-2002. Source: V&A

About the Context

From the sixteenth to the twentieth century, the corset was a vital piece of underwear for women. However, it is one of the most controversial garments in fashion history. Originating in aristocratic court culture, the corset was a symbol of nobility and wealth until it was worn by women of all classes (Steele 1). The main purpose of the undergarment was to slim a woman’s waist whilst providing support to the bust resulting in the desired feminine silhouette of the era.

Figure 2 is an eighteenth-century corset that is referred to as a ‘stay’. It is a stiff, boned garment that would have supported the women’s bust, slimmed the waist, and pushed their shoulders back. A ca. 1890s corset is featured in figure 3. This French corset illustrates the fashionable silhouette at that time: a full bust, nipped-in waist, and curved hips. The corset is made from cotton twill and is structured with baleen and steel bones to keep its rigidity. The similarities in shape, such as the slimmed waist and neckline, are clear to see in Westwood’s corset and the eighteenth-century corset in figure 2.

Vivienne Westwood and Jean Paul Gaultier began to use underwear as outerwear in the 1980s. In Westwood’s 1982 collection, Nostalgia of Mud, she featured the Mud Bra (Fig. 4). Gaultier designed the cone bra dress in 1984 (Fig. 5), a play on the cone bra which came out in the 1950s. However, Vivienne Westwood was the first twentieth-century designer to revive the corset in its original form in 1987 (V&A), and it continued to be incorporated in fashion designs by designers throughout the 1990s (Fig. 6).

Fig. 2 - Designer unknown (French). Women's corset, ca. 1730-1740. Silk plain weave with supplementary weft-float patterning. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (French). Corset, ca. 1890s. Cotton twill. Online: The Underpinnings Museum, KL-2020-012. From the collection of Karolina Laskowska. Source: The Underpinnings Museum

Fig. 4 - Vivienne Westwood (British, 1941-). Mud Bra, 1982. Synthetic satin. London: Victoria & Albert Museum, T.238-1985. Given by Mr Patrick Moore. Source: V&A

Fig. 5 - Jean Paul Gaultier (French, 1952-). Dress, Fall/Winter 1984-1985 Ready to Wear. Orange shirred velvet. New York: The Museum at FIT, P92.8.1. Museum purchase. Source: MFIT

Fig. 6 - John Galliano (British, 1960-). Corset top, Spring/Summer 1993. Source: Vogue

Fig. 7 - Vivienne Westwood (British, 1941-). Corset, 1987. Red synthetic velvet and black wool. Source: Vivienne Westwood

In The Corset: A Cultural History (2011), Valerie Steele wrote, “Westwood’s revival of the corset may be one of her most important contributions to late twentieth-century fashion” (166). Westwood first reintroduced the traditional corset shape in her Harris Tweed collection in 1987 (Fig. 7). Westwood called the corset ‘Stature of Liberty,’ emphasizing how they were no longer constricting undergarments, instead bold statements of female liberation (Kendall). Westwood reiterated the same message when she featured this corset in her Portrait collection in 1990.

It is important to note, as Steele stresses, that “Corsetry was not one monolithic, unchanging experience that all unfortunate women experienced before being liberated by feminism” (1). Her book debunks the myth that corsets were entirely enforced by a patriarchal society. The experience of wearing a garment is subjective and this monolithic, oppressive view positions women as uniformly passive and oppressed. Steele shows that many arguments about corsetry being detrimental to the health of the wearer do not hold up to scrutiny as corsets could not have caused all the health issues and illnesses some claimed they did (68). In the case of Westwood reclaiming the corset, she wishes to retire the oppressive myth of corsetry, and celebrate it as a garment of female power and liberation, as demonstrated by her naming the corset in the Harris Tweed collection ‘Stature of Liberty.’

The Portrait Collection, 1990

In the documentary Why I Love the Wallace about The Wallace Collection, which owns the Boucher painting she printed on the corset, Vivienne Westwood said:

“All my ideas come from studying the ideas of the past. There is a link between art and fashion. I couldn’t design a thing if I didn’t look at art.”

One of Westwood’s favoured sources of inspiration is The Wallace Collection, in London, which is known for its extensive collection of 18th-century decorative arts and paintings. For Westwood, it represents a high point of culture from 18th Century Britain which she wanted to celebrate and therefore, she based the Portrait collection on it (Westwood).

Fig. 8 - John Van Hasselt. Models kiss as they wear outfits during a fashion show by British designer Vivienne Westwood, 1990. Getty Images. Source: AnOther Magazine

Fashion in the 1980s and 90s saw a revival of 18th-century society in popular culture (Dorogova). Fully embracing the taste and style of The Wallace Collection, Westwood styled her models entirely on 18th-century paintings. For example, models wore pearl accessories as though they may have just stepped out of the paintings (Dorgova). Westwood was keen to include an actual painting in her collection, thus she printed Boucher’s Daphnis and Chloe painting onto the corset.

Never one to play it safe, Westwood included two models who kissed on the runway (Fig. 8), just as Daphnis and Chloe seem poised to do. As Westwood once said in an interview, “I play around with the idea of sexuality because I don’t like orthodoxy in any shape or form.” (Westwood). The models were dressed in the corset, thus building on the ideas of the Portrait collection corset being a metaphor for female liberation.

Daphnis and Chloe, François Boucher, 1743

Fig. 9 - François Boucher (French, 1703-1770). Daphnis and Chloe, 1743. Oil on canvas; 109.5 x 154.8 cm. London: The Wallace Collection, P385. Koucheleff-Bezborodko collection, St. Petersburg; c. 1865-69, bought by Richard Seymour-Conway, 4th Marquess of Hertford.. Source: The Wallace Collection

Written in the Roman Empire, the Ancient Greek novel tells the story of Daphnis and Chloe who were both abandoned at birth. Chloe was found by Dryas, a shepherd, and Lamon, a goatherd, discovers Daphnis. Growing up together, Daphnis and Chloe fall in love, however they can’t comprehend what their feelings are. Various characters pitch in to try and help Daphnis and Chloe make sense of their feelings. One character suggests the cure is kissing. Whilst another explains love making to Daphnis, including details of the discomfort and bleeding Chloe may experience. These details put Daphnis off engaging in such activities with Chloe. Time passes during which Daphnis and Chloe are separated. Chloe is courted by suitors and Daphnis is abducted by pirates. Recognising them, Daphnis and Chloe’s birth parents come to the rescue and return them to safety. Chloe and Daphnis reunite and get married, living out the rest of their lives happily together.

For her corset, Vivienne Westwood honed in on the erotic section of the painting. Westwood’s corset, featuring Daphnis and Chloe in lust, leaves a memorable impression of the subversion of a garment which no longer confines women, but liberates them.

Its Afterlife

The corset is now a regular feature on the runway, arguably as a result of Westwood’s innovative use of the historic garment. Many fashion designers continue to use the corset in their collections (Figs. 10, 11). Westwood’s original period corset from 1990 also continues to be worn and celebrated as a breakthrough fashion moment of the twentieth century. In figure 12 it is worn by the singer-songwriter FKA Twigs in 2019. No longer is female sexuality concealed and eschewed, instead Westwood brings it to the fore, celebrating it by subverting the purpose of this historical garment. As Steele wrote, “the meaning of any item of clothing is not embedded in the clothing itself; it’s something we create and are constantly renegotiating” (Bramley). This is certainly true for Westwood’s corset.

Fig. 10 - Saint Laurent (French, 1961-). Look 46, Fall 2019 RTW. Source: Vogue Runway

Fig. 11 - Tomor Koizumi (Japanese, 1988-). Look 12, Fall 2019 RTW. Source: Vogue Runway

Fig. 12 - Photographer unknown. FKA Twigs at Sundance Film Festival, February 2019. Source: Vogue

References:

-

Bramley, Ellie Violet. “Let Loose: How the Corset Is Being Reclaimed by the Fashion Industry.” The Guardian, April 1, 2017. http://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2017/apr/01/corset-new-female-power-suit-vivienne-westwood-madonna-miuccia-prada.

- Dorogova, Waleria, “Ensemble from the “Portrait” Collection, Vivienne Westwood Ready-to-Wear, Fall/Winter 1990-1991”, Fashion Photography Archive, London: Bloomsbury, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474260428-FPA177

- Kendall, Zoë, “How Corsets Took Over the World”, i-D, 2020. https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/wxq8v5/how-corsets-took-over-the-world

- Longus, Daphnis and Chloe, Penguin Classics, England: Penguin Books, 1989. https://www.worldcat.org/title/daphnis-and-chloe/oclc/1129638322&referer=brief_results

- “Painted Ladies”, Channel 4 Documentary, 1996, Part 1: “Nobility, Virtue and Nobility”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fyswGKKhdAw Part 2: “Aesthetic Lust”, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlkTluY-e_c Part 3: “Luxury and Frivolity,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7MlIkXdlOjc

- Steele, Valerie, The Corset: A Cultural History, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2011. https://www.worldcat.org/title/corset-a-cultural-history/oclc/993523680&referer=brief_results

- “The Corset in Late 20th Century Fashion”, The Victoria and Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-corset-in-late-20th-century-fashion/

- Vivienne Westwood: Why I Love the Wallace. Video. The Wallace Collection, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v_-XK5WaZEo