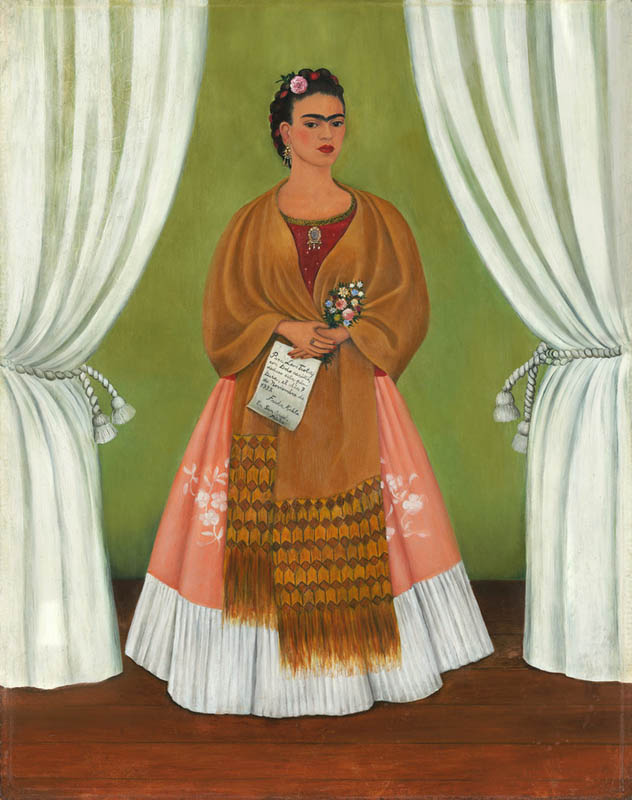

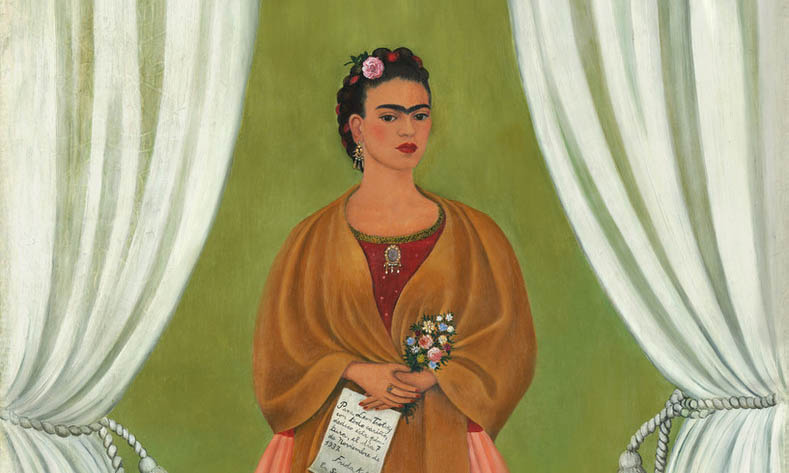

Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky shows a front-facing Frida Kahlo holding a letter with a bouquet of flowers in her arms. Brilliant white curtains flank each side against a green background to reveal an elegantly dressed Frida, who adopts elements of Mexican Zapotec dress.

About the Portrait

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907-1954) is known for her distinctive personal style, dream-like and shocking paintings that reflect her personal life, and infamous marriage to Mexican muralist painter, Diego Rivera.

According to the National Museum of Women in the Arts, this portrait memorializes the affair between Kahlo and exiled Russian revolutionary leader, Leon Trotsky, during his arrival to Mexico in 1937. The NMWA states the dedication to Trotsky reads:

“Para Leon Trotsky con todo cariño, dedico ésta pintura, el dia 7 de Noviembre de 1937. Frida Kahlo. En San Ángel, Mexico.

For Leon Trotsky with all my love, this portrait is dedicated on 7 of November 1937. Frida Kahlo. In San Ángel, Mexico.”

The compositional elements reinforce the focus on Kahlo, which harks back to similar compositional techniques used in retablos, vernacular devotional paintings, of the Virgin of Guadalupe (NMWA), which elevates Kahlo’s portrait to a goddess-like devotion to love.

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954). Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, 1937. Oil on masonite; 76.2 x 60.9 cm (30 x 24 in). Washington: National Museum of Women in the Arts. The Honorable Clare Boothe Luce. Source: NMWA

About the Fashion

Frida Kahlo is known to wear a Zapotec style of dress derived from Tehuanas, Zapotec women from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Sayer, Figs. 1 and 2). The typical style consists of a floral patterned huipil (tunic) and skirt, trimmed with starched lace, gold and silver jewelry worn on the ears, wrists, and neck, with bright ribbons decorated with fake or fresh flowers. This style has variations all over Mexico and Guatemala, each with different contexts and Kahlo wore versions from both areas (Sayer). Within this portrait, Kahlo’s attire is more subtle and plain in comparison to her other portraits. She wears a green-trimmed red blouse with a bejeweled pendant, a beige rebozo, and a pink skirt with white flowers and trimmed with white pleats. Her hair is in a Tehuana traditional braid with red ribbon and one pink flower in her hair. Her face is made up with rouge, lipstick, and her prominent unibrow. She wears one ring and holds a bouquet of flowers. Her ensemble blends late-30s beauty trends with traditional clothing.

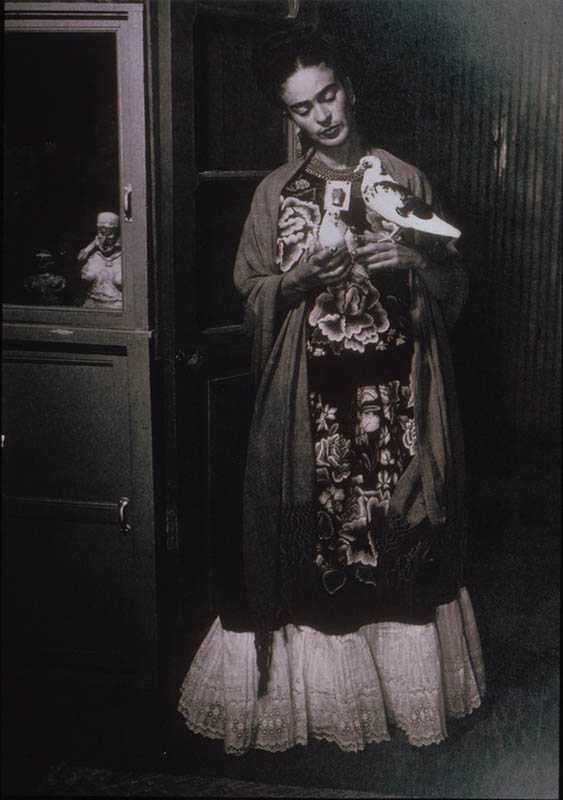

Fig. 1 - Juan Guzmán (German born Mexican, 1911-1982). Frida with Two Birds, ca. 1940s. New York: Throckmorton Fine Art Gallery. Source: Artstor Digital Library

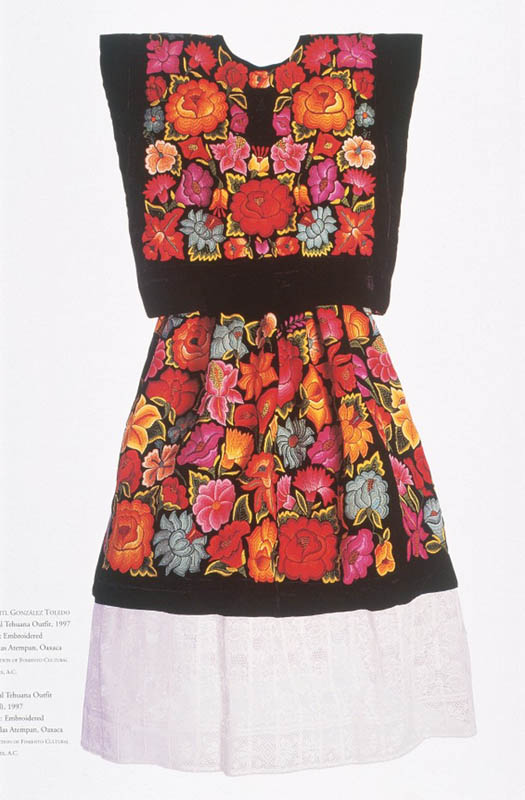

Fig. 2 - Xóchitl González Toledo. Typical Tehuana Outfit from San Blas Atempan, Oaxaca, 1997. Embroidered velvet. Mexico: Fomento Cultural Banamex. Source: Artstor Digital Library

Fig. 3 - Lola Alvarez Bravo (Mexican, 1907-1993). Girl embroidering huipil, Tehuantepec, n.d. Gelatin silver print; 19 x 22.5 cm (7 1/2 x 8 7/8 in). Tucson: Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Lola Alvarez Bravo Archive, 93.6.43. Source: Artstor Digital Library

A huipil (Fig. 2) is a sleeveless tunic worn by women throughout Mexico and Guatemala with a lineage dating back to two thousand years ago (Sayer). The backstrap loom technique is traditionally used to create a huipil, but can be embellished through embroidery, lacework, braided, and ribboned as seen in figure 3. According to Francie Chassen-Lopez in The Traje De Tehuana as National Icon: Gender, Ethnicity, and Fashion in Mexico (2014), the earliest image of a huipil is from the Vatican Codex, which shows a woman wearing a V-shaped huipil that stops below her hips (306). Some traditional huipils are still made by hand (Fig. 4), but most modern huipils are brightly decorated and machine-made. Within the portrait, Kahlo is not wearing her iconic huipils, but is wearing a bejeweled red blouse possibly made at the time of the portrait or created from her mind using popular trends (Fig. 5/Museo Frida Kahlo).

Fig. 4 - Designer unknown (Mayan). Woman’s Blouse (Huipil), ca. 1930. Cotton, silk; discontinuous supplementary weft patterning; 56.52 x 100.81 cm (22 1/4 x 39 11/16 in). Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Art, 98.273.43. Gift of Richard Simmons. Source: MIA

Fig. 5 - Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, 1890-1973). Evening Blouse, 1936-1937. Silk. Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, 2009.300.2377. Gift of Millicent Huttleston Rogers, 1951. Source: The Met

Fig. 6 - Designer unknown (Mexican). China Poblana, ca. 1925. Blouse: cotton plain weave with bead and sequin embellishment; skirt: felted cotton plain weave; printed and with sequin embellishment; shawl (rebozo): rayon plain weave with ikat-dyed patterning. Providence: RISD Museum, 1996.84. Gift of Barbara White Dailey. Source: RISD Museum

A rebozo is a long, rectangular shawl traditionally worn by women and seen as a symbol of womanhood (Sayer). They come in various colors, styles and are generally worn around the shoulders (Fig. 6 and 7). The reservado/jaspe, also known as the ikat technique, is how most of the rebozos are produced. Color sequences are created through tie-dying selected warp threads before weaving (Sayer). Rebozos have many uses: they can protect from the cold and convert into a sling to carry goods and infants (Sayer). In Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, Kahlo’s rebozo is a perfect example of the ikat technique and shows how the ends are knotted to form fringe. The painting simplifies the knots, but the knots act as an embellishment and practical tool for tying off ends.

Most of Kahlo’s skirts, demonstrated in the painting and in figure 1, are known as enaguas which means “petticoat.” However, they are not worn under larger skirts, instead, they are their own article of clothing. They fasten at the side with fabric ties and usually have a detachable cotton lace flounce known as a holán (Fig. 8/ Sayer). Mexican textile specialist Chloë Sayer states that patterned cloth was imported from Manchester, England, and became fused into the local fashion (Sayer). Sayer also draws a distinction between the enagua and rabona: “The enagua is still used on the Isthmus for formal occasions, [while] the rabona, a lighter style with a pleated flounce of [printed cotton]…remains a popular item of everyday wear on the Isthmus” (Fig. 9). Self-Portrait demonstrates an example of the rabona style with an holán: the blush-pink skirt has minimal decoration of white floral patterning, possibly printed, in contrast to the more elaborate enagua in figure 8.

Fig. 7 - Antíoco Cruces and Luis Campa (Mexican). Buñolera [seated woman wearing rebozo selling buñuelos], ca. 1870-1875. Carte-de-visite. Davis Museum at Wellesley College: Wellesley, 2011.173.5. Museum purchase with funds given by The Gruber Family Foundation through the generosity of Linda Wyatt Gruber. Source: Artstor Digital Library

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown (Zapotec). Woman's Skirt, 20th C.. Musée du Quai Branly: Paris, 70.2008.61.141. Source: Artstor Digital Library

Fig. 9 - Designer unknown (Zapotec). Skirt, n.d.. Cotton fiber, silk fiber, dye. Vancouver: Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia, E206 b. Source: Museum of Anthropology

Its Legacy

To close out this discussion about the basic elements of Tehuana-style dress, Francie Chassen-Lopez writes about the relationship between the wearer and their clothing:

“The tehuana’s dress acquires a symbolic life of its own independent from the body of the woman who wears it: a ‘look’ that is uprooted from place and, as such, accessible to women in many different places as an icon of a national identity…[and] is nothing without the woman wearing it…the women’s erect posture as they walk…each wearing a different combination of hues that shimmer in the bright sun, vying for attention with the colorful flowers and produce…the body functions as a dynamic field…[with] the traje’s charge of ethnicity is fluid and depends on whether the body wearing it is white, mestiza, or indigenous…[a] ‘second skin,’ intricately entwined with her sense of individual and specifically Zapotec cultural identity…. [However], for a non-Isthmian woman, the traje serves to provide a white or mestizo body with a generic indigenous identity, enabling it to temporarily participate in the rich culture and history of indigenous Mexico” (310).

There has been ongoing discussion of Kahlo’s appropriation of the Tehuana and how it displaces Isthmian women who traditionally wear the traje (Kale). Chassen-Lopez points to the appropriation of the traje in white and mestizo bodies as being a symbol of pride, whether national or personal. Kahlo’s attire points to her pride in being able to glamorize her body in pain with folkloric finery of ribbons, jewels, and bright colors (Fuentes 8). Self-Portrait points to an illusion of divine seduction of her lover, Leon Trotsky and the flowers, jewelry, and warm tones act as a dynamic confession of love cemented in paint that continues to uplift Kahlo as a fashion icon within the Latinx identity.

References:

- Chassen-Lopez, Francis. “The Traje De Tehuana as National Icon: Gender, Ethnicity, and Fashion in Mexico.” The Americas 71, no. 2 (October 2014): 281-314. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43189263

- Fuentes, Carlos. Introduction to The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait, 8. New York: Abrams, 2005. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/966141419

-

“The Dresses of Frida Kahlo.” Museo Frida Kahlo, https://www.museofridakahlo.org.mx/en/exhibitions/.

- Sayer, Chloë. “Traditional Mexican dress.” Victoria & Albert Museum. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/traditional-mexican-dress

- Wall text, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. Accessed December 28, 2020. https://nmwa.org/art/collection/self-portrait-dedicated-leon-trotsky/

![Buñolera [seated woman wearing rebozo selling buñuelos] Buñolera [seated woman wearing rebozo selling buñuelos]](https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/image008.jpg)