About the Look

I

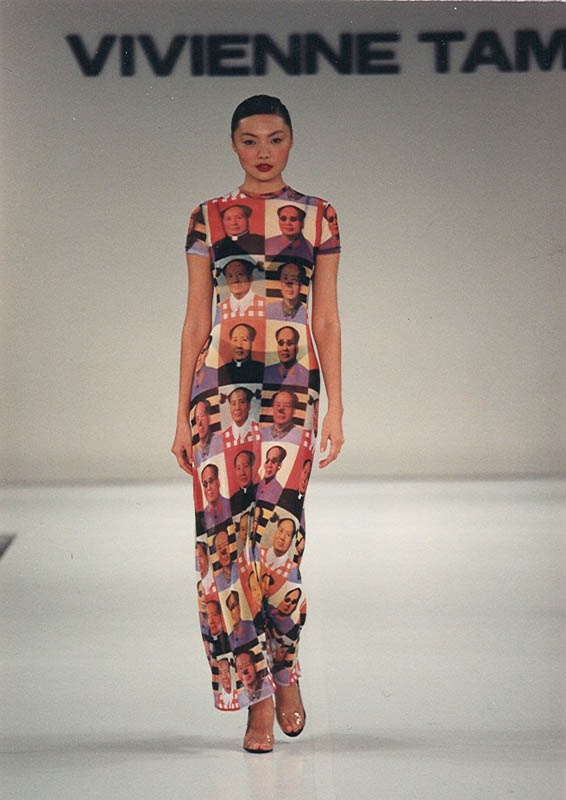

n November 1994, Vivienne Tam presented her spring 1995 collection, which would become one of the most notable of her career. Known as the “Mao collection,” it was comprised of t-shirts, dresses, and skirt suits featuring comical images of Mao Zedong (1893-1976), the founding father of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and former chairman of the Communist Party of China. This collection was a collaboration between Tam and Chinese artist Zhang Hongtu.

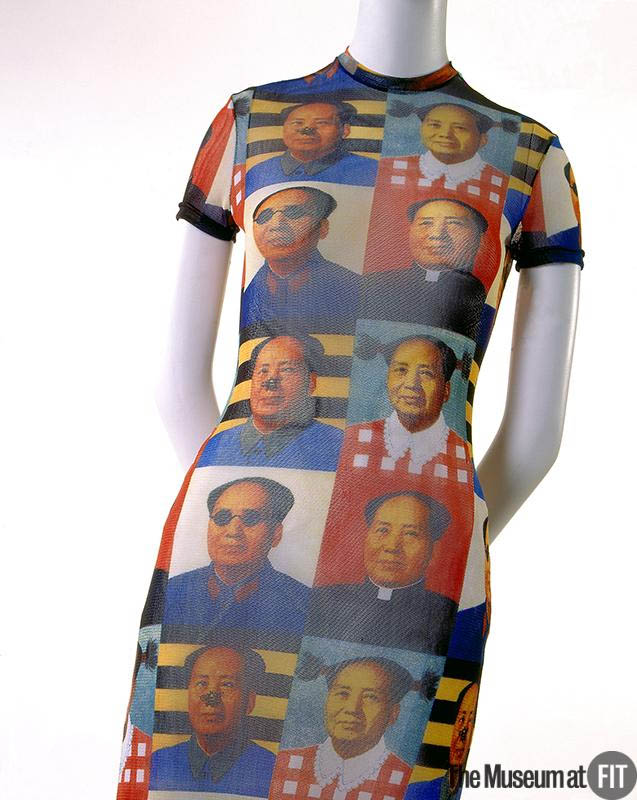

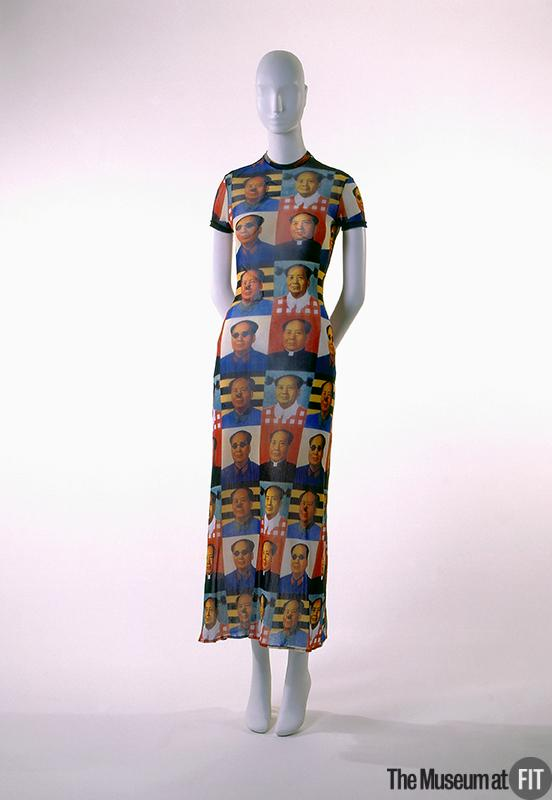

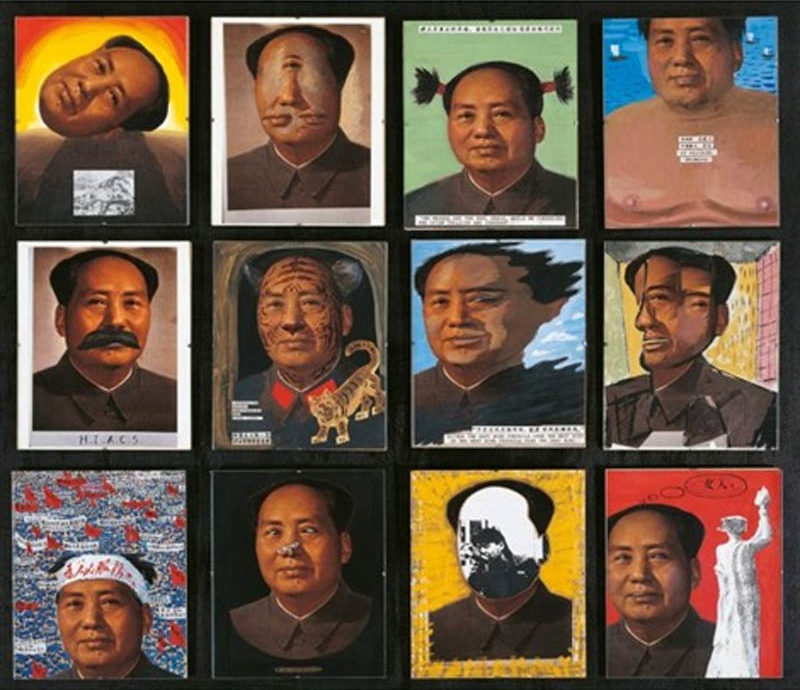

This multicolored nylon dress features a checkerboard pattern of humorous images of Mao by Zhang Hongtu (Fig. 1). The portraits include “Mao so Young” (pigtails and gingham dress”, “Ow Mao” (bee on his nose), “Holy Mao” (clerical collar), “Psycho Mao” (dark hypnotic glasses), “Miss Mao” (smear of lipstick), “Nice day Mao” (smiling face). The checkerboard pattern was intended to reflect “Mao’s changeable character” (Tam 88). Tam and Hongtu also used these portraits to be on printed t-shirts, embellished with sequins which make the designs come alive as they move in the light (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 - Vivienne Tam (Chinese, 1957-). Dress, 1995. Multicolor nylon. New York: The Museum at FIT, 95.82.6. Gift of Vivienne Tam. Source: MFIT

Fig. 2 - Vivienne Tam (Chinese, 1957-). Dress, 1995. White cotton, clear sequins, yellow polyester crepe. New York: The Museum at FIT, 95.82.1. Gift of Vivienne Tam. Source: MFIT

Vivienne Tam (Chinese, born 1957). Dress, 1995. Multicolor nylon. New York: The Museum at FIT, 95.82.6. Gift of Vivienne Tam. Source: MFIT

About the context

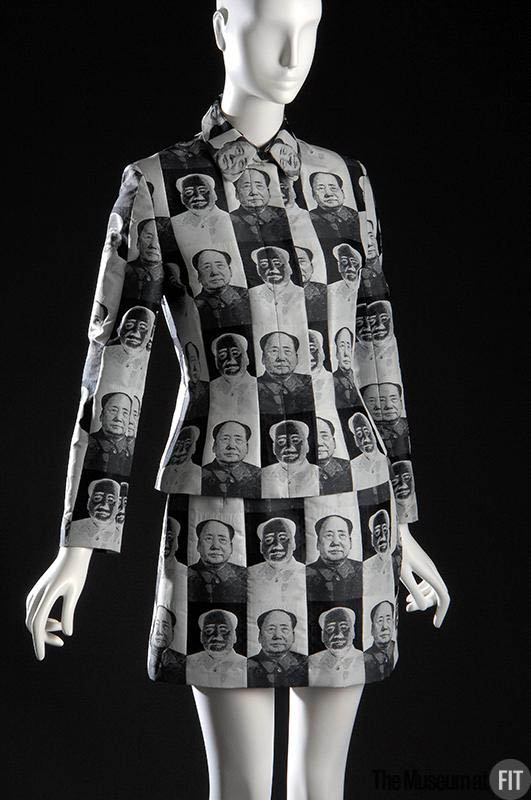

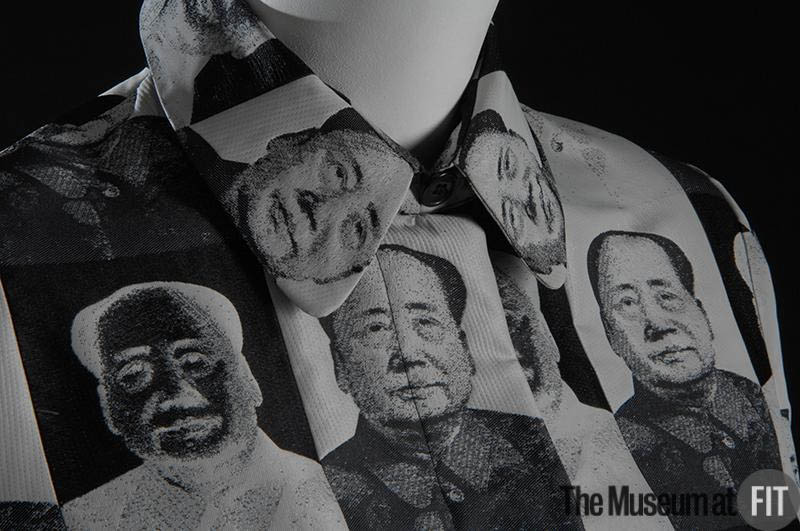

Tam also designed garments with black and white images of Mao for the Spring 1995 collection, which “were more serious, symbolizing the positive and negative effects Mao had on Chinese culture” (Tam 88). This matching polyester jacket and skirt suit (Fig. 3) featured a repetitive pattern of the same Mao portrait, which is still hung in Tiananmen Square. The jacket closely resembles elements of the suit Mao regularly wore, which is called the Zhongshan suit, also known as the “Mao suit” (Fig. 4). A major trend from the spring 1995 collections included black and white skirt suits with the same standing collar, also known as the “Mao collar.” This tailoring technique was seen in collections by Chanel, Calvin Klein, and Prada (Figs. 5-7). However, none of the designers made an impactful political statement like Vivienne Tam.

About the Designer

Vivienne Tam was born in Guangzhou in 1957, almost ten years after Mao formed the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Since her family was wealthy and owned land, they were targeted by the communist party. To escape political unrest during Mao’s regime, Tam’s family escaped to Hong Kong when she was three years old. Growing up in Hong Kong, Tam’s upbringing was a blend of Eastern and Western cultural influences. She returned to China in the late 1970s to a completely different world than she grew up in. After Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution in 1966, the communist party eliminated the four olds, Old Ideas, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Customs, to which fashion was included. The qipaos and Western suits from the 1920s and 1930s were replaced with the Zhongshan suit and military-like clothing.

Fig. 5 - Chanel (French, 1910-). Look 18, Spring 1995 RTW. Source: Vogue Runway

Fig. 6 - Prada (Italian, 1913-). Look 1, Spring 1995 RTW. Source: Vogue Runway

Fig. 7 - Calvin Klein (American, 1942-). Look 26, Spring 1995 RTW. Source: Vogue Runway

Tam went on to study fashion design at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University. To enhance her fashion career, she moved to New York in 1983 (Goodman). Her work often included Eastern inspirations. During the early nineties, while Tam was living in New York, China experienced a Mao cultural revival. People incorporated his image on a variety of items to reflect on the past and as a form of political satire. Many avant-garde Chinese artists used Mao’s image in their work, which sold very well. One of the first Chinese artists to do so was Zhang Hongtu (Fig. 8).

About the Artist

Zhang Hongtu was born in Gansu province in 1943. His father was a leading scholar, which led him to be denounced by Mao’s regime. Growing up under Mao’s leadership, Zhang explained, “like everyone of my generation, I completely trusted in Mao” (Tu 145). However, he would later witness situations like a student being brutally beaten for sitting on a newspaper featuring Mao’s portrait. In 1969, Zhang graduated from the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts in Beijing, where he studied painting. To build up his art career, he moved to New York in the early 1980s, which was when he began experimenting with painting Mao in a humorous light. After the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 (Fig. 9), he focused on manipulating Mao’s image as “a kind of mental therapy.” When he first started working with Mao’s portrait, Zhang experienced a sense of guilt, as if he was “committing a sin” (Tam 92). He explained, “You have to understand how powerful his image is for my generation. During the Cultural Revolution, in my teens, he was like a god” (Tu 152). Zhang created multiple works featuring Mao including Chairman Mao (12 works), Les Banquet, and Material Mao.

Fig. 8 - Zhang Hongtu (Chinese, 1943-). Chairman Mao (12 works), 1989. Acrylic on paper collage. Private Collection. Source: Artnet

Fig. 9 - Photographer unknown. Tiananmen Square Protests, 1989. Source: PRI's The World

About the Spring 1995 Collection

In 1994, Tam was introduced to Zhang and they collaborated for her spring 1995 collection. Tam explained, “His art was political, but I thought I could loosen it up a bit with fashion, to represent the openness of China. This would show its humor and warmth, and the growing freedom of its people from Mao’s image” (Tam 88). However, once the designs were completed, Tam had trouble manufacturing the collection. Due to the power Mao’s image still held, dozens of factories refused her order. When one finally accepted and completed the garments, they were sent to Tam disguised in layers of brown paper.

Fig. 10 - Vivienne Tam (Chinese, 1957-). Dress, Spring 1995. Courtesy of Vivienne Tam. Source: NBC News

Fig. 11 - Andy Warhol (American, 1928-1987). Mao, 1972. Acrylic, silkscreen ink, and pencil on linen; 448.3 x 346.7 cm (176.5 x 136.5 in). Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1974.230. Mr. and Mrs. Frank G. Logan Purchase Prize and Wilson L. Mead funds. Source: Art Institute of Chicago

Fig. 12 - Designer unknown. "Talking Fashion: Raging Red" In Vogue, vol. 188, no. 6 (June 1998). Source: The Vogue Archive

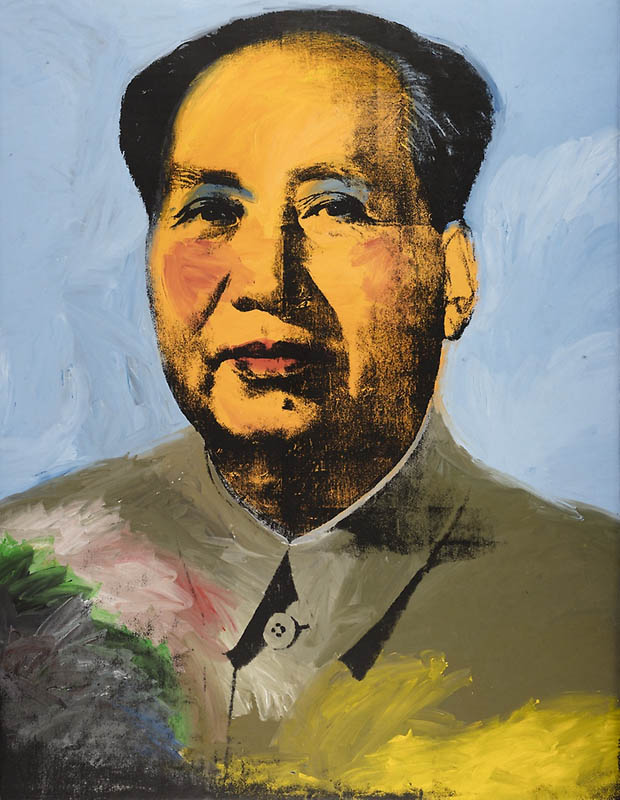

Once the collection was shown in New York in November 1994 (Fig. 10), the reactions were mixed. Zhang explained, “People who looked at the collection had different reactions to the images depending on where they were from and the bodies that wore them” (Tam 88). For example, some buyers did not know who Mao was and one asked if it was a portrait of Tam’s father. Others made the connection to Andy Warhol’s Mao portraits (Fig. 11). However, Zhang explained the difference of the two artist’s motives:

“Yes, Warhol just took the image of Mao as another mass icon, like Marilyn Monroe. But for Chinese artists, Mao is a political figure. I’ve been asked, ‘if Mao was a dictator like Hitler or Stalin, how can it be okay to use his image as pop art? Isn’t it tasteless to make fun of the suffering they caused?’ Good question. Mao is still controversial. Today, even if his deeds are criticized, the government still uses his ideologies, image, and flag. I believe that any use of Mao’s image which makes him less godlike is a form of criticism and it’s necessary.” (Tam 94)

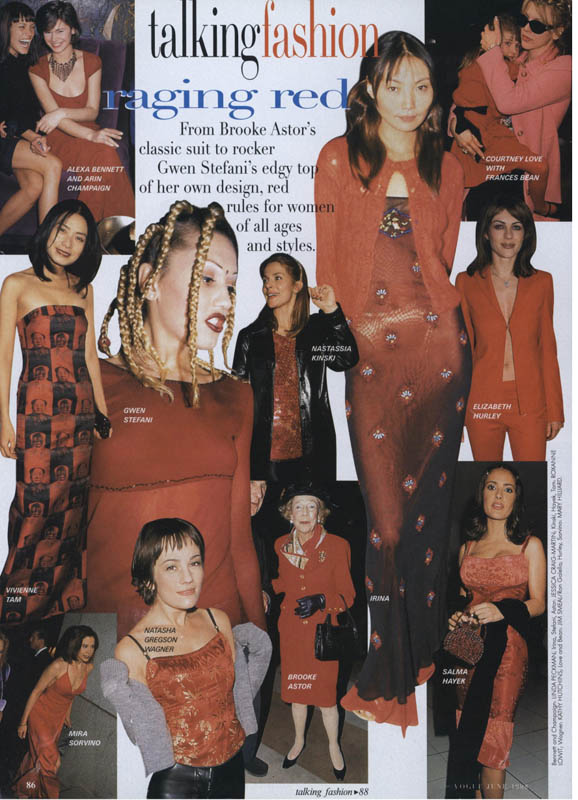

When the collection was available for purchase in stores, the controversy did not stop. Shops in Taiwan would not carry the collection and some American stores decided not to display the clothes. At Tam’s Hong Kong store, the sales associates experienced angry protestors who threw stones at the t-shirts featured in the window (Veridiano). While the garments received a lot of press and attention, not all was negative. Japan was very open to the idea of the collection. Vivienne Tam, herself, was also featured in one of her Mao dresses in Vogue in June 1998 (Fig. 12). However, a few months after the article came out, Vogue published a letter from one of their readers which read:

“I am shocked that the images of Mao Tse-tung can turn into a fashion statement. Mao directly and indirectly caused a lot of people to suffer beyond Vogue’s and my imagination. People lost their basic freedom and had to flee their country. My family was forced to burn all family pictures during the Cultural Revolution. I won’t be surprised to see the images of Hitler and Pol Pot making the latest trends! Seeing Mao preserved in fashion is an insult to all people who lost their basic human rights to him.”

It is important to note that while Tam’s collection did receive a lot of press, many did not report on Zhang Hongtu’s contribution or the message the two tried to convey.

Its Afterlife

V

ivienne Tam’s spring 1995 collection would change her career. Through her clothes, Zhang and Tam successfully combined fashion and art to highlight China’s past and present political issues. In Thuy Linh Tu’s The Beautiful Generation: Asian Americans and the Cultural Economy of Fashion, Tu explains:

“The collection pointed to the possibility that Asian images could, in this cultural economy, be more than just a floating signifier. They could serve as a resource to narrate cultural memories, and to reaffirm the importance of history, here posited neither as time or place, but as a set of questions to be continually repeated.” (24)

The “Mao collection” is now included in museum collections around the world, including The Museum at FIT, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Victoria and Albert Museum (Figs. 12, 13). Tam is now an established designer in both the Asian and Western market. In 2016, Tam relaunched the collection with Opening Ceremony for an initiative to highlight Chinese fashion.

Fig. 12 - Photographer unknown. Exhibitionism: 50 Years of The Museum at FIT, 2019. New York: The Museum at FIT. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 13 - Photographer unknown. China: Through The Looking Glass, 2015. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Source: The Guardian

References:

- Goodman, Wendy. “Her Serene Highness.” New York Magazine. Last modified April 17, 2003. https://nymag.com/nymetro/shopping/homedesign/features/n_8641/.

- “Talking Back.” Vogue 188, no. 9 (Sep 01, 1998): 172. https://libproxy.fitsuny.edu:2365/magazines/talking-back-bridal-bouquet-stealing-beauty/docview/879308480/se-2?accountid=27253. [subscription required]

- Tam, Vivienne. China Chic. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/795560414.

- Tu, Thuy L. The Beautiful Generation: Asian Americans and the Cultural Economy of Fashion. Durham: Duke University Press, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1158602084.

- Veridiano, Ruby. “Inspired by China, Designer Vivienne Tam Has Always ‘Thought Differently’.” NBC News. Last modified September 7, 2016. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/inspired-china-designer-vivienne-tam-has-always-thought-differently-n643431.