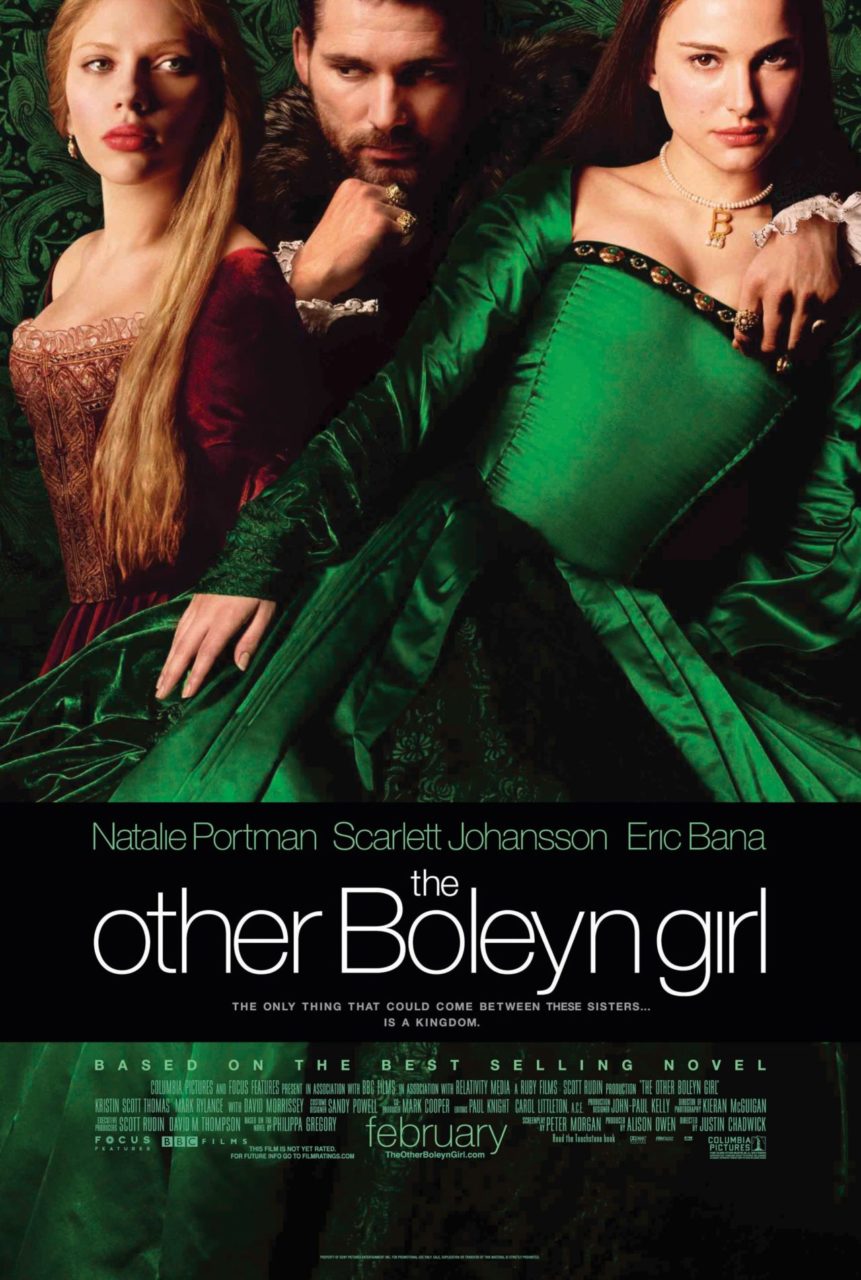

The Other Boleyn Girl (2008)

Synopsis

Two sisters, Mary and Anne Boleyn, contend for the affection of King Henry VIII.

Directed by

Justin Chadwick

Release date

29 February 2008 (USA)

Costume Designer

Sandy Powell

Studio

- Columbia Pictures

- Focus Features

- BBC Films

- Relativity Media

- Ruby Films

- Scott Rudin Productions

Source: IMDB

Film trailer

Introduction

On the heels of the 2007 blockbuster sequel Elizabeth: The Golden Age, the 2008 film The Other Boleyn Girl continued to captivate the imagination with a vision of the Tudor Dynasty. The Other Boleyn Girl directed by Justin Chadwick starred Natalie Portman as Anne Boleyn, Scarlett Johansson as Mary Boleyn, and Eric Bana as Henry VIII (IMDb). It was an adaptation of the 2001 novel of the same title by Philippa Gregory (fig. 1). The film and book were about the political climb of Anne Boleyn and the Boleyn family during the reign of Henry VIII in the 1520s and early 1530s (Sony). The film condensed the Boleyn family’s rise, which took over ten years, into a three-year time span. With a production budget of thirty-five million dollars, the film earned seventy-five million dollars doubling its profit. The Other Boleyn Girl was filmed in Kent, England in Dover Castle, Knole Castle, and Penshurst Place. Hever Castle, the Boleyn family estate during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, is also in Kent, and Henry VIII loved visiting Knole Castle in the early part of his reign (Kent Film Office). The director did not mention why the film was not produced in Hever Castle, but the location is open to the public. The film’s costumes were crucial in communicating character development, and depicted a period in England of conspicuous consumption by the royalty and aristocracy. I will be describing and analyzing the costumes of Anne Boleyn, which are used to communicate her transition from a humble lady into a boisterous Queen.

The film chronicles the Boleyn family’s political rise, by using Mary and Anne Boleyn to gain favor with Henry VIII. At the beginning of film, we briefly see Anne and Mary, and their brother George as children. Then there is an immediate cut to them as adults at Mary’s wedding to William Carey. The Boleyn Sister’s ascendance actually began around 1513 when they were sent as teenagers to France to be educated on court life while in the service of Henry VIII’s sister, Queen Mary, who married Louis XII in 1514 (PBS). Several years later, Mary Boleyn returned to England, and was maneuvered into becoming the King’s mistress, and bore him a son. Henry VIII and his wife Catherine of Aragon had a daughter, Mary, but because of primogeniture laws and social norms, Henry longed to have a son to be his heir. However, no illegitimate child could be an heir to the throne. Mary Boleyn’s rise at court was short lived once Anne returned to England in 1522 to be a lady in waiting for Queen Catherine (PBS). The following year, Anne married Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland, in secret; Anne’s father and uncle immediately annulled the marriage, and sent her to live at Hever. When Anne came back to court to be in service to the Queen again in 1526, the king began to pursue Anne fervently (PBS). According to British screenplay writer Richard Bevan, Anne captivated the king using the art of flirtation she learned in France (BBC). After giving into Anne’s demands to be with her, Henry divorced Catherine. The Pope was the only authority that could dissolve royal marriages; the Pope denied Henry’s request to divorce Catherine to remain peaceful with Spain, Queen Catherine’s home country. Pressure to marry Anne led King Henry to break from the Catholic Church, and establish the Church of England with himself as the head in September 1533, which led to the English Reformation (fig. 2). Directly after their wedding, Anne bore a daughter named Elizabeth. Anne had several miscarriages and a stillborn, which distressed the King. In May 1536, Henry VIII concocted charges of witchcraft and incest against Anne; she was beheaded ending her brief reign as Queen of England, and the Boleyn family fell from the King’s grace (PBS).

Fig. 1 - Philippa Gregory (1954-). This is the novel that inspired the film., 2001. Source: Good Reads

Fig. 2 - Artist unknown (English). Portrait of Anne Boleyn, 1533-1536. Oil on panel; (21 3/8 in x 16 3/8 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 668. Purchased 1882. Source: National Portrait Gallery

About the Period Setting

Henry VIII’s reign was during the High Renaissance; Italy dominated the luxury market. Moreover, much of the Italian style was incorporated within English fashion. Women’s dress began with a linen chemise, which was uniform throughout Europe (fig. 3). Over the chemise was the corset made with linen and stiffened with wood or whalebone; it gave a conical shape to the upper body (Mikhaila, 23). In the royal court and among upper classes, the corset was accompanied by the farthingale, a hooped skirt made of linen, and was also reinforced with wood; it gave a conical shape to the lower body. According to Ninya Mikhaila in her The Tudor Tailor: Reconstructing Sixteenth-century dress, Catherine of Aragon brought the Spanish farthingale to England when she married Henry VIII’s older brother Arthur 1501 (Mikhaila, 21). In addition to the farthingale, padded hip rolls or “bum rolls” were worn to support women’s skirts. According to fashion historian Hebert Norris, Henry VIII’s first daughter Mary wore the farthingale very often, expressing that it became the height of fashion during the 1520s and 1530s in England (Norris, 216). While the farthingale was not universally worn in England, it was highly fashionable at European courts by the 1530s, and it is likely that the Boleyn sisters were accustomed to wearing farthingales during their time as ladies-in-waiting in France. A petticoat, also named the kyrtle, was worn over the farthingale (Norris, 224). The front region of petticoats called the forepart was sometimes embroidered or exquisitely designed using a silk or gilt thread (fig 4). As high-ranking aristocrats, Mary and Anne Boleyn likely had the forepart of their petticoats made of silk that were woven or embroidered with gold and silver threads.

The next layer of a woman’s costume was her dress, consisting of a bodice and skirt. Fashionable bodices had low square necklines embroidered with precious stones like pearls (fig. 5). For the sake of modesty as well as decoration, women could also wear partlets, small pieces inserted into their necklines (fig. 5). As in the Italian style, sleeves in England were constructed in two parts. The upper sleeves fit tightly from shoulder to the elbow, and then wide, flaring cuffs lined in contrasting materials such as silk velvet or fur, and sometimes heavily embroidered, were turned up and stitched in place (Mikhaila, 13). Katherine Parr, Henry VIII’s last wife, was portrayed wearing sleeves with cuffs lined in ermine, the fur most associated with royal status (fig. 6). Fashionable women’s dresses had the lower part of the sleeve, which was padded and open, held together by ties to allow the chemise to pour out of the sleeve. The skirt of the dress, worn over the petticoat, had its fullness pushed toward the back to create a train and expose the highly decorated forepart. Wool and silk were the primary fabrics used to produce dresses, using a plain, velvet, or satin weave.

A fashionable outerwear garment was the ropa; originating from Portugal and Spain, it was a long-padded vest or coat with a high collar (fig. 7). They were made using heavy fabrics such as silk velvet. The accessories Englishwomen wore in the 1530s were the focus of fashion, and were highlighted in the film. The Gable Hood was a distinctively English fashion. It was a stiff, angular headdress that encased a woman’s face, and had two draped veils hanging in the back (fig. 8). During the 1530s, it was in vogue to pin one of the veils allowing one to hang freely. The French Hood, which can be seen in the portrait of Anne Boleyn, had a rounded shape, and allowed some of the hair and more of the face to be exposed (fig. 2). The French Hood had a single veil connected to the back. Other fashionable accessories in the 1530s were jeweled chain belts, gold rings and necklaces set with precious stones. Once they were favorites of the King, Anne and Mary probably wore petticoats and dresses embroidered with the finest jewels in Europe.

Fig. 3 - Maker unknown. Shirt and Chemise, sixteenth-century. Linen. Bath, England: Fashion Museum, Bath. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 4 - Titian (Italian, 1488-1576). The Impress Isabel of Portugal, 1548. Oil on canvas; (46 in x 39 in). Madrid: Museo del Prado, P00415. Royal Collection (Palace of El Buen Retiro, Madrid, 1772, no. 616?; Palace of El Buen Retiro, 1794, no. 440?; New Royal Palace, Madrid, "secretaría de Estado", 1814-1818).. Source: Museo del Prado

Fig. 5 - Bronzino (Italian, 1503-1572). Portrait of a Young Woman, 1545. Oil on canvas; (22.8 in x 18.3 in). Florence: Uffizi Gallery. Source: Wikipedia Commons

Fig. 6 - Master John (English). Katherine Parr, 1545. Oil on canvas; (71 in x 37 in). London: National Portrait Gallery, NPG 4451. Purchased with help from the Gulbenkian Foundation, 1965. Source: National Portrait Gallery

Fig. 7 - Antonio Moro (Dutch, 1517-1577). Catherine of Hapsburg, the Wife of King John III of Portugal, 1552-1553. Oil on canvas; (42.1 in x 33 in). Madrid: Museo del Prado, P02109. Royal Collection. Source: Museo del Prado

Fig. 8 - Hans Holbein (English, 1497-1543). Jane Seymour, 1536. Oil on canvas; (236 in x 16 in). Wien, Austria: Kunthistorisches Museum. Source: Web Gallery of Art

About the Costume Design

In the film, as the character of Anne Boleyn evolved, her costumes became more sumptuous. In the beginning of the film, Anne’s costumes imply hidden luxury; the costumes are not ostentatious displays like the costumes of Henry VIII. In the second scene of the film, Anne wears a green dress with a matching gold brocade on the bodice and petticoat to Mary’s wedding (fig. 9). The petticoat protrudes outward signifying an understructure like a bum roll creating the skirt’s triangular shape. The bodice is very stiff, indicating that it may be boned in addition to being worn over a boned corset. Over the petticoat is a silk satin forest green skirt that is attached to the bodice using ribbons running along its side. The sleeves of the dress are three-quarters length with ribbons on the hem, which reveal the bodice’s gold brocaded sleeve. Under the bodice is a partlet made of a sheer fabric, such as chiffon. Her accessories include a French hood without the veil, and a pearl necklace. In a later scene, when Henry VIII is a guest at the Boleyn home, Anne was tasked with enchanting the King. While hunting with Henry, she wears a burgundy riding ensemble (fig. 10). This ensemble illustrates how adventurous she was while remaining alluring. She wore a long silk velvet ropa, that is lined with yellow silk satin. The sleeves on Anne’s ropa are fitted with heavy ruching in the shoulders, elbows, and cuffs to emulate the heavy padding of women’s sleeves of the 1530s. The dress she wears underneath comprises a slashed bodice made of the same materials as the coat, and a silk satin skirt, which has a gold floral pattern. She wears a sheer partlet that is held with a choker, and a gold metallic snood cap that holds her hair when hunting. As seen worn by Eleanor of Toledo in her 1545 portrait by Bronzino, the snood was an embroidered netted cap that was Italian fashion; wearing the snood in the film communicates Anne’s familiarity with international fashions (fig. 11). Under this costume, Anne also wears a bum roll; her accessories are a red beret and matching leather gloves.

When the Boleyn family initially arrives at court, Mary and Anne become Queen Catherine’s ladies-in-waiting. The costumes Anne wears during this point in the film delineate her transition into court life; many of the women at court, such as Queen Catherine and her ladies-in-waiting, are wearing more conspicuous costumes. Anne’s garments are slightly more lavish than those she wears at Hever, but her style retains remnants of her old life. A noticeable difference between Anne’s dresses and those worn by the ladies of the court is the silhouette. The court ladies’ skirts are wide and round as if they are wearing cage crinolines of the nineteenth-century, while Anne wears a bum roll that makes her appear smaller and slender, and therefore making her more attractive and accessible to the audience (fig. 12). Furthermore, in the scene when Anne and Mary are presented to the Queen, she wears a blue dress with a matching French Hood without a veil (fig. 13). The bodice of the dress has silk velvet paneling along its side. The slashed shoulders, slashed cuffs of the sleeves, and the skirt are made of the same blue silk velvet. She also wears a sheer chiffon partlet and pearl necklace. The front of the bodice and petticoat are made of blue silk satin with a repeating ring pattern down the center, which was probably used to emulate the embroidery of the sixteenth-century. She is wearing a bum roll under the blue dress as she did in Hever, suggesting she has not completely adjusted to court fashion. There is a major scene during the climax that represents the end of her adjustment to court fashion; she is chastised for marrying Henry Percy in secret by her uncle and father. In the scene, she wears the same light green gold silk embroidered bodice and petticoat she wore to Mary’s wedding in the beginning of the film (fig. 14). The only difference is that she wears a snood, and a grey velvet cropped sleeveless vest with ribbon enclosures instead of the green dress. This is the final dress she wears that’s reminds the audience of her previous life; she is sent to the court of the Queen of France as punishment for marrying Henry Percy in secret, and her marriage was annulled. She is sent to France to learn how to properly behave in a royal court, and eventually returns a few months later with a vengeance while Mary is on bedrest carrying the King’s child. This transition in the movie is also a prime example of the film’s writers taking creative licenses condensing the actual history of Anne Boleyn.

The first scene where Anne makes an appearance since her exile in France is during the King’s dinner. During this dinner, everyone at court is eating and laughing at Anne’s jokes. When the King is annoyed by the laughing, he asks her to stand before him. She is shown wearing the most recognizable dress from the film, which Portman wore in advertisement posters. The costume consists of an emerald green silk satin dress and matching French hood with a veil (Fig. 15). This dress represents her complete transformation as a leading figure of the court. The bodice of the dress is very stiff, the neckline low and square, and bordered with pearl embroidery on a black silk velvet ground. The sleeves of the dress are fitted, but the cuffs are folded back to her elbow revealing the velvet lining, which emulates the fashionable sleeves of the 1530s. Her petticoat is also emerald green silk satin, and has a gold thread floral pattern. The silhouette of this costume is also wide and round, like that of the court ladies. Her most notable accessory is a pearl necklace with a gold letter “B”, which appears in a portrait said to be based upon another a lost original done during her lifetime (fig. 2). In the film, the appearance of the necklace signals character development. In earlier scenes, Anne wore a pearl necklace, but without the “B.” The letter “B” represents her renewed spirit, and her desire to rise in the court’s social ranks. Anne wears this green dress in different versions throughout the rest of the film; each new costume becomes more elaborate as she rises to become Queen of England (fig. 16). There is only one costume that falls outside of Anne’s uniform fashions that is significant to note, which is in the scene when her sister Mary gives birth. In the dining room in front of Mary’s bedroom, the King swears to Anne that he will break off his relationship with Mary. The moment Mary finishes giving birth, the King leaves the apartment without acknowledging Mary or his child signifying that Mary no longer has his favor. During this scene, Anne wears a heavy forest-green silk velvet dress with a high neckline (fig. 17). The upper sleeves are fitted with the cuffs turned upward revealing the silk satin lining. Additionally, she has a lower sleeve that is brown and silk velvet; the two-part sleeve of this dress is very accurate with the period’s fashions. Anne also wears an olive-green silk satin petticoat, and a gable hood with a green silk cover. Anne’s forest-green ensemble in this scene illustrates her complete assimilation into the drama and dangers of court life to achieve her mission of becoming Queen.

When Anne becomes Queen of England, there are three costumes that illustrate her new status, and her downfall: her coronation dress, the costume she wears to testify in court, and the dress she wears for her execution. Anne Boleyn was Queen from June 1533, and she was executed May 1536. Anne’s coronation dress is stately; it is comprised of an indigo-colored dress with a yellow silk gold-embroidered cape lined with ermine (fig. 18). Because she is pregnant during the coronation, the dress has a higher waistline. The bodice is velvet, and the sleeves are silk satin slashed and ruched in the shoulders, elbows, and cuffs revealing the yellow silk satin lining. The skirt is a silk textile woven with pomegranate motifs, the specialty of Italy, which were coveted luxuries during the Renaissance. Anne’s pregnancy creates the billowing silhouette of the costume. When the coronation was finished, Anne switches her crown for a matching Gable Hood with a chiffon veil. This luxurious dress represented the peak of Anne’s ascendancy, but the darker color was a contrast from the bright green and blue dresses she had previously worn. This suggested her uncertainty as the new Queen of England. Green was a symbol of confidence she had during her rise, but she began to wear darker blue and black dresses as her relationship with Henry deteriorated. Towards the end of the film, Anne is charged with witchcraft, and is commanded to testify. In this scene she wears a heavy black velvet dress with gold thread floral embroidery, and a matching black Gable Hood (fig. 19). The neckline is low and embroidered with precious stones like many of her costumes by this point in the film. This dress is the most accurate to the Tudor fashions. Black was a fashionable color influenced by the Spanish, and was commonly worn among the English aristocracy (Boucher, 227). The Gable Hood in this scene is very accurate; generally, the French and Gable Hoods seen in the film are inaccurate. In comparison with actual hoods from the 1530s depicted in portraits, the shapes of Anne’s hoods in the film are not extremely angular, and sometimes are worn without a veil. Furthermore, the black dress she wears for her trial has the cuff turned to her elbows, and a narrow chain belt, which was very fashionable during the 1530s. Anne’s last costume, seen in the execution scene, was significant. The dress consisted of a navy-blue silk satin skirt and fitted bodice covered with an ermine caplet (fig. 20). Down the center of the bodice and the skirt is a heavy blue medallion embroidery that blends into the dress. The silhouette of the costume’s skirt is smaller, created with a bum roll rather than a farthingale. Anne no longer wears the big farthingale understructure while she is imprisoned and executed communicating her fall from grace. The return to this silhouette reminds the audience of Anne’s beginnings at Hever. She also wore a Gable Hood that she took off before being beheaded.

Fig. 9 - Sandy Powell. Anne Boleyn at Mary Boleyn's wedding, 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 10 - Sandy Powell. Anne Boleyn's Hunting ensemble, 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 11 - Bronzino (Italian, 1503-1572). Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo, 1545. Oil on canvas; (45 in x 38 in). Florence: Uffizi Gallery. Source: Wikipedia

Fig. 12 - Sandy Powell. Lady Jane Parker addressing Queen Catherine, 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 13 - Sandy Powell. Anne Boleyn being presented to Queen Catherine, 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 14 - The Other Boleyn Girl. Anne Boleyn and Mary arguing after Anne's marriage to Henry Percy is revealed to her uncle and father., 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: DVDizzy.com

Fig. 15 - Sandy Powell. Anne Boleyn's at the King's dinner., 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 16 - Sandy Powell. Anne's uniform fashion, 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: The Costume Vault

Fig. 17 - Sandy Powell. Anne's costume when Henry promises to end his relationship with Mary to be with her., 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 18 - Sandy Powell. Anne Boleyn's coronation ceremony., 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Fanpop.com

Fig. 19 - Sandy Powell. Anne Boleyn's trial., 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

Fig. 20 - Sandy Powell. Anne Boleyn's execution., 2008. The Other Boleyn Girl. Source: Pinterest

About the Costume Designers

The costume designer for The Other Boleyn Girl was the seasoned Sandy Powell. Some of the films that she has designed for include Orlando (1992), Shakespeare in Love (1998), and many more (“Sandy Powell,” IMDb). She is one of the premiere costume designers for period films, especially films that have a Renaissance or Baroque setting. She won an Academy Award in 1999 for her designs in Shakespeare in Love and in 2009 for The Young Victoria, and received numerous Oscar and British Academy of Film and Television nominations cementing her position as one of the leaders in the field. In an interview with Costume Designers Guild, Powell discussed briefly what she wanted to achieve through the costumes; Powell was very determined to make the costumes in The Other Boleyn Girl elaborate as possible (Dawson). She expressed that her goal was to use Anne’s and Mary’s costumes to figuratively communicate their relationship throughout the story; Mary and Anne start out as loving sisters on an equal footing, and once they come to court, Anne’s ambition strains their relationship (Wycoff). Once Anne began rising to become Queen, her costumes become more conspicuous and gloomy. Conversely, as Mary leaves court life, her costumes become more luminous reflecting the peace she gains being away from the royal court life drama.

Powell mentioned she wanted to create costumes that were precisely with the 1530s English fashions despite the budget (Wycoff). She felt it was necessary to show the Gable and French Hoods to combat the stereotype that striking period fashions take attention away from the actors. She believed hoods helped frame the actors’ faces, and brought the viewers’ attention to the dialogue. In the film’s crew, there were several hairstylists including Paul Gooch, Lisa Pickering, and Ivana Primorac that also contributed significantly because they attempted to emulate the English hairstyle of the 1530s. Anne’s hair is long and straight for the first half of the film; long hair represented youth and being unmarried, which is accurately depicted before her marriage to Henry. Conversely, when Anne is married, her hairstyles inaccurately alternate from being straight to being pinned up; married women wore their hair pinned as a sign of modesty during the Renaissance.

Historical Accuracy

Powell was born in London and attended Central Saint Martins. She would have certainly had either prior knowledge on Tudor-era fashions or used the numerous resources at her disposal from all over England including the National Portrait Gallery where the portraits of Anne Boleyn are held, the British Museum, the Courtald Institute, the Fashion Museum in Bath, and many others. She could have drawn from her earlier experiences creating the Elizabethan costumes in Shakespeare in Love and Orlando. Powell wanted to make the costumes as accurate to the 1530s as possible, but she had to find a balance between achieving the period fashions and ensuring that the costumes supported the actors in their performances. A major inaccuracy of Anne’s and the other women’s dresses in the film is their silhouette. The correct understructure worn under Tudor-era skirts were bum rolls or farthingales that created an angular, conical shape. The skirts in the film, however, look like they have nineteenth-century cage crinolines under them, creating a dome-shaped silhouette. The use of color in the costumes, though it served the purpose of characterization, is also inaccurate. Anne’s signature color, green, was very unusual in the Tudor-era. Until the nineteenth-century, green required the use of two dyes, blue and yellow, and the resulting color was highly unstable. Another major inaccuracy was the patterned textiles that Anne wore like the skirt of her hunting ensemble. The patterns appeared flat as if they were printed onto the textiles. Printed textiles, such as printed cottons made in India, were extremely rare in sixteenth-century England, though some materials were painted or stained to create flat patterns. Using practical printed textiles was probably intended to captivate and appease the eye of the contemporary audience.

Anne’s Gable and French Hoods were also modified to reflect the journey in her life; the hoods shapes changed throughout the film as she matured. In the beginning of the film, Anne wears French Hoods without a veil to signify her youth, but when she returns to court from exile, she wears French and Gable Hoods with veils. Additionally, Powell adapted the costumes to the major historic inaccuracies of the script. For example, when the King visits Hever Castle, Anne goes on a hunting trip with him; she rides astride on the horse, and does not have an escort. Powell had to create something sporty for Anne to wear to keep pace with the King, thus she created the red velvet ensemble, which was flexible for Anne to move around. This ensemble is very inaccurate, but it does not feel like an outlier from the rest of Anne’s costumes.

Influence on Fashion

The Other Boleyn Girl was an independent film, and did not receive high marks from film critics; many critics felt that it was melodramatic soap opera (Rotten Tomatoes). The film did not have any direct effect on fashion around 2007 – 2008, but there were designers during this period who were creating fashions that incorporated Renaissance inspirations, such as Ellie Saab’s Fall 2007 Haute Couture, Christian Lacroix’s Spring 2008 Haute Couture, and Givenchy’s Spring 2008 Haute Couture (fig. 21).

Fig. 21 - Elie Saab (Lebanese, 1964). Look 45 of Elie Saab Fall Haute Couture Collection, 2007. Source: Vogue.com

Conclusion

Despite the inaccuracies of the film, I think that this could be a valuable source for students of costume design and fashion history. There was an exhibition at Hampton Court in 2008 that used the costumes from The Other Boleyn Girl to explore the history of the Tudor dynasty (fig. 22). Seeing the costumes on mannequins without any distractions from the film would encourage the students to focus on the important aspects of each costume for their research. Costume designer students can use this film for insight into understanding how to balance representing a period style and appeasing the modern eye. Powell uses a lot of signifiers to stress the Renaissance setting, such as the Gable and French Hoods, the billowing dresses and bum rolls, and the heavy textiles. Also, Powell has produced some of the most profound work in the costume design field, thus I think costume design students would benefit from studying any of her work. Conversely, fashion studies students can use this as a starting point for their research. I would not advise that they base their understanding of mid-sixteenth-century fashion on The Other Boleyn Girl because it would be difficult to differentiate what is accurate, but the film could open opportunities to learn about Tudor-era fashions.

References:

- Beavan, Richard. “Anne Boleyn and the Downfall of her Family.” BBC, Accessed Oct 2, 2017. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/tudors/anne_boleyn_01.shtml

- Boucher, Francois. 1987. A History of Costume in the West. London: Thomas & Hudson Ltd.

- Dawson, Alene. “The Other Boleyn Girl: Clothe the Royal Court on an Indie Film Budget.” Variety, Accessed Oct. 6, 2017. http://variety.com/2009/film/awards/the-other-boleyn-girl-1117998050/

- Martin, Richard. 1997. Tudor Costume and Fashion. New York: Dover Publications.

- Mikhaila, Ninya and Jane Malcolm-Davies. 2006. The Tudor Tailor: Reconstructing Sixteenth-century dress. London: Batsford.

- “Pomegranate Velvet.” Cooper Hewitt Museum, Accessed Oct 6, 2017. https://www.cooperhewitt.org/2015/09/21/pomegranate-velvet/

- Ribeiro, Aileen. 2000. The Gallery of Fashion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- “The Other Boleyn Girl.” IMDb, Accessed Oct 2, 2017. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0467200/

- “The Other Boleyn Girl.” Kent Film Office, Accessed October 2, 2017. http://kentfilmoffice.co.uk/2008/02/the-other-boleyn-girl-2008/

- “The Other Boleyn Girl.” Sony Pictures, Accessed Oct 2, 2017. http://www.sonypictures.com/movies/theotherboleyngirl/

- “The Six Wives of Henry VIII.” PBS, Accessed Oct 2, 2017. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/sixwives/meet/ab_handbook_main.html

- Wyckoff, Anna. “Sandy Powell.” The Costume Designers Guild, Accessed Oct. 6, 2017. http://costumedesignersguild.com/articles-videos/articles-archive/spotlight-sandypowel