From the eighteenth century to the present day, women’s swimwear has undergone an unparalleled transformation. Changes in women’s swimwear throughout history have reflected sociological and technological factors, thus the garment acts as a barometer of time.

Swimwear is loosely defined as a category of garment often worn when participating in aquatic activities, such as swimming or bathing. Swimwear is expected to fulfil varying requirements. For competitive swimmers, a streamlined and tight-fitting garment which reduces friction and drag in the water is favoured to enhance propulsion and buoyancy. For recreational use, swimwear needs to be fashionable whilst also maintaining its functionality, for example protecting the wearer’s modesty and withstanding the effects of elements such as water and sunlight. Exploring the history of female swimwear, tracing how it has evolved through time and across continents, not only gives an insight into fashion trends and technological advancements in materials and design, but also an exploration of female liberation.

18th Century

In the eighteenth century, sea bathing became a popular recreational activity. It was believed that there were considerable health benefits to bathing in the sea, thus it was encouraged for both women and men (Kidwell). However, immersing oneself completely was discouraged. This was deemed particularly important for women as activity in water was not seen as sufficiently feminine. For bathing, women would wear loose, open gowns, that were similar to the chemise (Kidwell). These bathing gowns were more comfortable to wear in the water, especially when compared to more restrictive day clothes.

The bathing gown in figure 1 is from 1767 and belonged to Martha Washington, the wife of then-Continental Army commander, and later the first US president, George Washington. The blue and white checked gown is made from linen and is in an unfitted shift style. Small lead weights are sewn into each quarter of the dress, just above the hem. This was to ensure the dress did not float up in the water, helping women to maintain their modesty. It is known that Martha Washington travelled in the summers of 1767 and 1769 to the famed mineral springs in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia, to absorb the apparent health benefits.

Fig. 1 - Maker unknown (American). Bathing gown, ca. 1767-1769. Linen, lead. Mount Vernon: George Washington’s Mount Vernon, W-580. Gift of Mrs. George R. Goldsborough, Vice Regent for Maryland 1894. Source: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

19th Century

In the 19th century, the popularity of recreational aquatic activities surpassed the desire to bathe for health benefits. With this, the loose-fitting chemise gowns became increasingly fitted and more complex, replicating the silhouettes of women’s fashion.

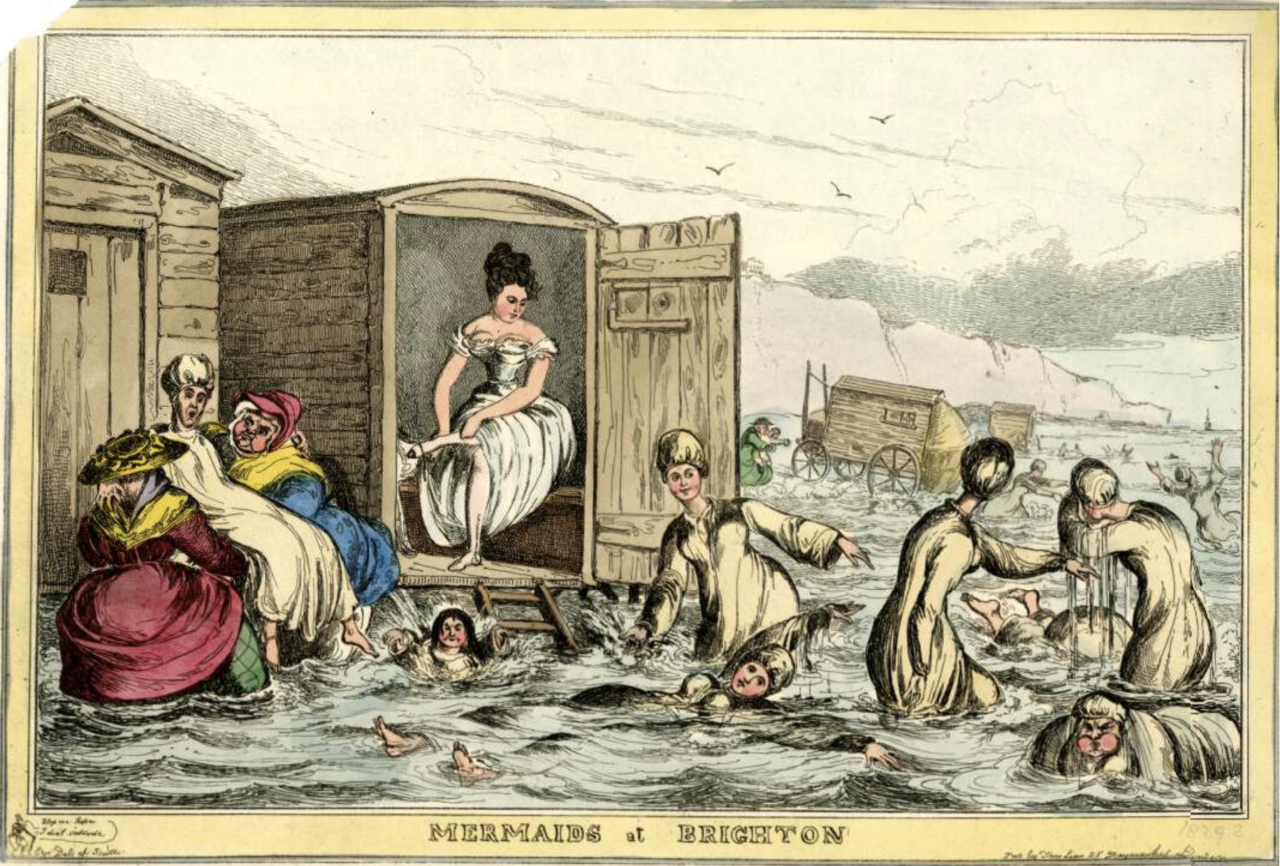

The number one priority for women who took part in water-based activities was to maintain their modesty. Whilst bathing for health benefits fell out of fashion, women still tended to bathe or paddle in water. This was because vigorous exercise in water was not considered ladylike. Women’s swimwear had to reflect this notion of remaining proper, as defined by contemporary society. Bathing outfits would consist of a bathing dress, drawers and stockings, often made of wool or cotton. These fabrics would become heavy when wet and were hardly suitable for any vigorous activities. In this case, it can be said that women’s swimwear, which prohibited ease of movement in water, reflected and maintained the social and physical constraints on women in nineteenth-century patriarchal society.

Fig. 2 - William Heath (British, 1794-1840). Mermaids at Brighton, 1825-1830. Etching. London: The British Museum, 1868,0808.9134. Purchased from Edward Hawkins (estate of). Source: British Museum

Fig. 3 - Designer unknown (American). Bathing suit, 1870s. Wool. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.346.18a, b. Gift of The New York Historical Society, 1979. Source: The Met

During the Victorian period, known for its strict moral values, women frequently used bathing machines, as pictured in figure 2, when getting in and out of the sea. Bathing machines were little houses on wheels that would be drawn in and out of deeper water by horses. They provided women with a place to change in privacy before making their way directly into the sea.

Into the 1880s, women continued to wear bathing dresses, as seen in figures 3 and 4. These garments had high-necks, long-sleeves, and knee-length skirts. Linen and wool fabrics were still used. Women often wore belts at the waist to replicate the popular silhouette of the time. Under the bathing dress, women would wear bloomer-like trousers to maintain their modesty.

An alternative female swimwear garment, popularised towards the end of the Victorian era, was the Princess suit (Kennedy 23). These were one-piece garments where the blouse was attached to the trousers. On top, women wore a mid-calf length skirt which diverted attention from the wearer’s figure. The garments tended to be dark colours, which meant onlookers could not tell if the garment was wet. The suits were not the most practical, restricting the wearers’ arm movements and weighing them down in the water.

The Princess suit was a catalyst for the considerable changes to women’s swimwear that was to come. Most obviously, the Princess suit was the beginning of the one-piece swimsuit for women (Fig. 5). Changes began to happen quickly as women’s activities in water began to be more socially acceptable. Firstly, by the 1890s, the trousers of the Princess suit were shortened so they could not be seen under the skirt. The material that was used to create a Princess suit moved away from flannel, which became heavy when wet, towards serge and other knitted materials (Kidwell).

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. Bathing Costume, from The Delineator, July 1884. Washington D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution, photo 58466. Source: Alamy

Fig. 5 - Maker unknown (American). Bathing suit, 1890-95. Wool, cotton. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975.227.6. Gift of Theodore Fischer Ells, 1975. Source: The Met

1900-1945

During the twentieth century women’s swimwear underwent significant transformations as a result of the material advancements and increasingly liberal fashion trends.

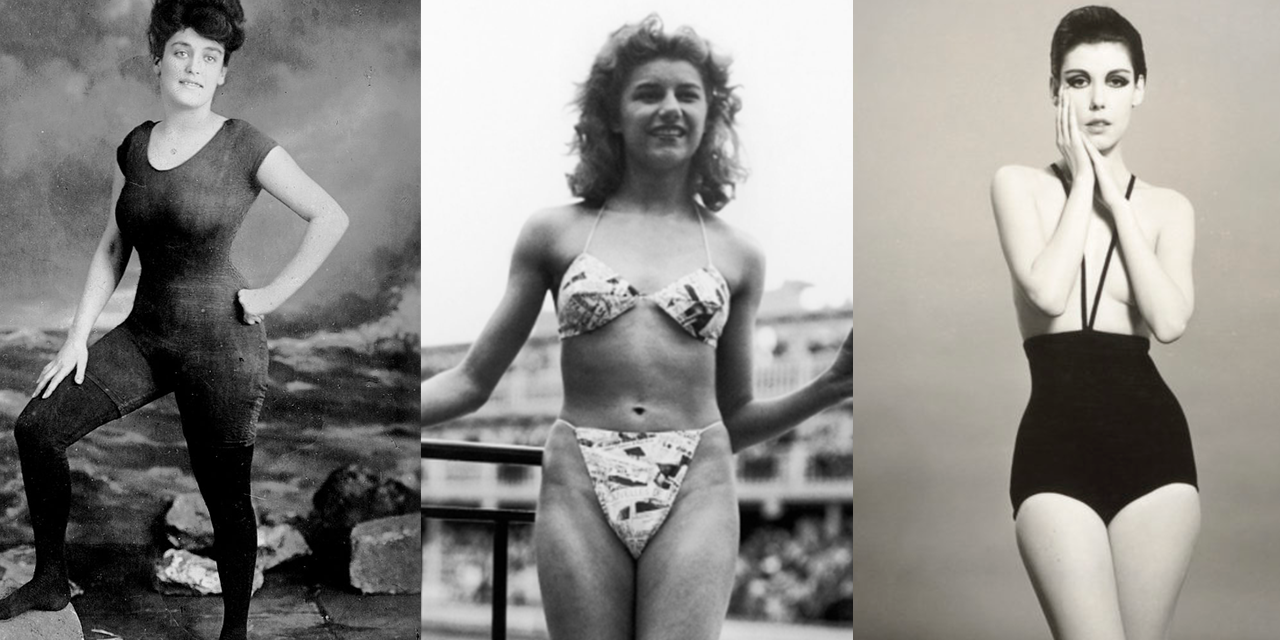

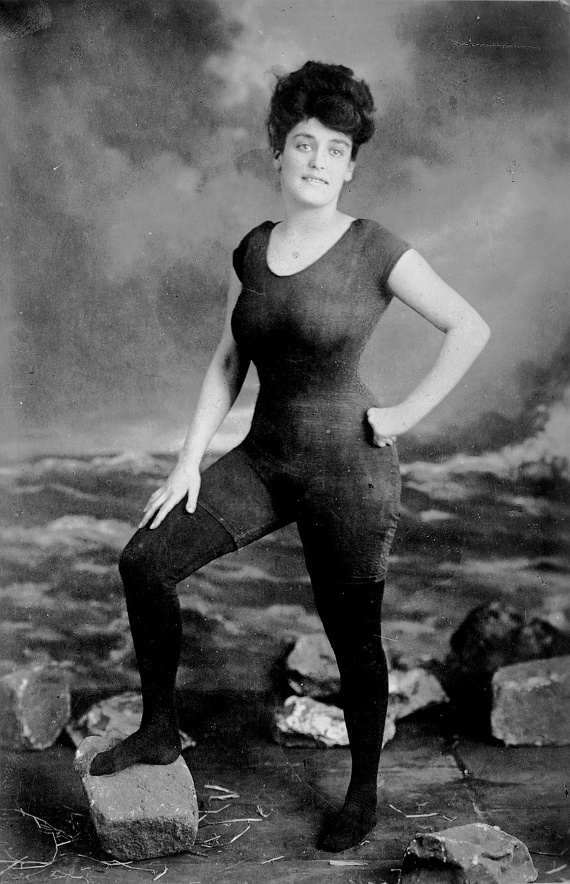

In the early nineteenth century swimming emerged as a competitive sport. However, its popularity was not solidified until its first appearance at the Olympic Games in 1896. Women were permitted to compete in swimming for the first time at the 1912 Olympics. Annette Kellerman (Fig. 6), a swimmer from Australia, can be credited for shifting social attitudes towards acceptance of female participation in swimming and beginning the modernization of female swimwear. Kellerman was dubbed “the Australian Mermaid” because of her swimming capabilities. She was known for swimming the English Channel and famed for her performances in Hollywood movies (Schmidt and Tay).

In 1905, Annette Kellerman was invited to perform in front of the British Royal Family, however her swimsuit was prohibited as it was tight-fitting and revealed the lower half of her legs. Kellerman refused to compete in an inconvenient and ill-fitting garment which would meet their modesty standards, so she instead sewed black stockings onto her swimsuit, as seen in figure 6. Kellerman encountered trouble again when she competed in Boston. Her swimsuit was deemed to be of indecent exposure; however, this was overruled in her favour as the judge agreed that heavy and ill-fitting swimsuits were impractical garments for swimming. This incident was widely publicised in the media, and whilst Kellerman’s action could have had a liberating effect on female swimwear, it unfortunately led to a crackdown on female immodesty in some parts of the world, with police working to enforce strict clothing conduct policies.

Fig. 6 - George Grantham Bain (American, 1865-1944). Miss Annette Kellerman, ca. 1905. Glass negative. Washington D.C.: Library of Congress, LC-B2- 738-5 [P&P]. Source: LOC

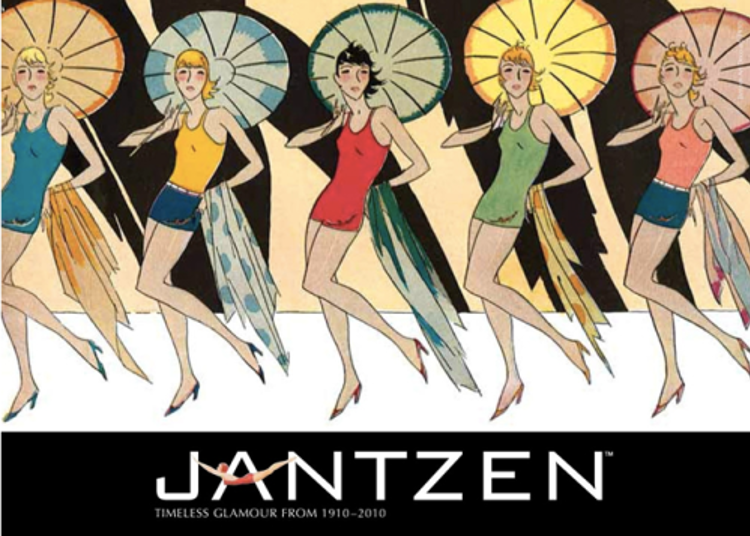

Fig. 7 - Jantzen (1910-). Jantzen 1910-2010, 2010. Source: Lingerie Talk

In the 1910s, Jantzen, originally known as the Portland Knitting Company, was the leading producer of bathing suits (Fig. 7). This was the start of technological advancements in the materiality of swimwear. At first, Jantzen produced what they referred to as ‘woollen suits’ for rowing clubs. This became very popular and so Jantzen marketed it to a wider audience. It was not until 1921 that Jantzen referred to the garment as a swimsuit. Speedo, the Australian clothing company, started to experiment with swimwear in 1914. For both sexes, the all-in-one garments tended to have short sleeve or vest style tops with long legs. Whilst social reform had begun, the commercial sector lagged behind. Therefore, both Jantzen and Speedo continued to market their all-in-ones as bathing suits throughout the 1910s.

Following the First World War, women’s swimwear trends began to differ across continents. In America and Europe women wore knitted swimwear which replaced the bathing suit, however there were slight tweaks depending on where you lived. In America, women favoured a practical and sporty look whilst European women opted for sleeker swimsuits which cut closely to the body. Another key difference between the two fashion trends was that women’s swimsuit fashions were accessible to a very large middle class in America, whereas in Europe there were clear class divisions on what women could or could not afford to buy for wearing to the beach. An affluent woman could set herself apart by wearing a silk jersey swimming suit, instead of a knitted one (Kidwell). Kennedy reiterates this when she wrote:

“Both sides of the Atlantic favoured the practical one-piece ‘maillot’, but in France the costume’s legs were shorter in length, the knitted ribwork was more finely woven and the decoration was kept to a minimum.” (34)

Whilst the maillot costumes worn by women were improvements on what they had to wear before the turn of the century, they still had their impracticalities. Due to the materiality of the garment, the knitted swimsuits tended to become misshapen when wet. The fabric absorbed a great deal of water resulting in the elongation and sagging of the swimsuit. These issues often jeopardised the modesty of the women’s swimsuits which concerned inter-war society.

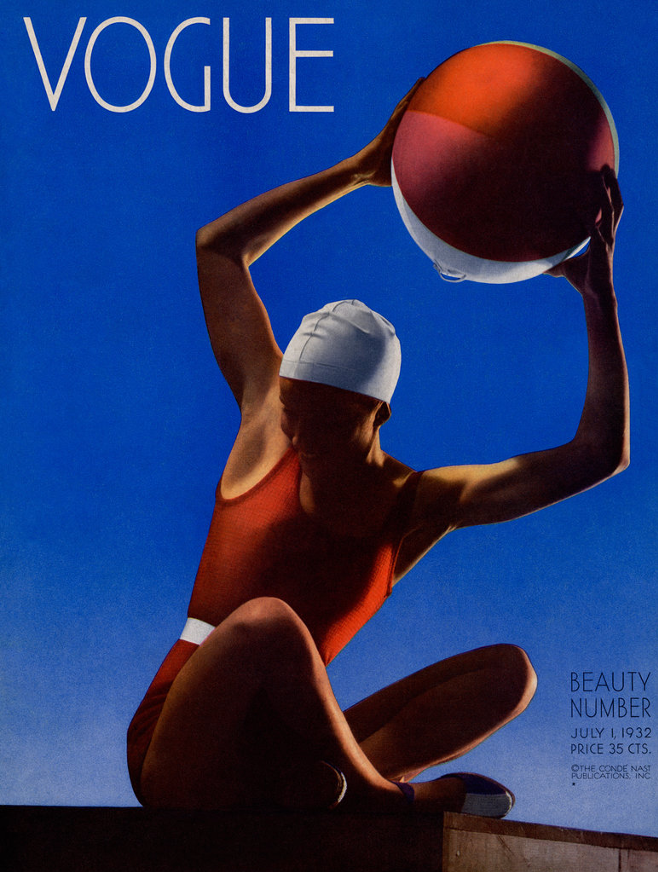

Fig. 8 - Photographer unknown. Vogue Cover, July 1932. Source: Vogue Archive

Fig. 9 - Neyret (French). Bathing Costume, 1937. Machine-knitted wool. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, T.293-1971. Source: V&A

During this period, swimwear began to feature in magazines as fashionable garments (Fig. 8) as fashion designers turned a hand to creating swimwear. Coco Chanel created a one-piece swimsuit, woven from a boucle fabric, that could have almost passed as unisex (Kennedy 48). Chanel’s foray into swimwear brought it into modern fashion. Jean Patou, who worked with his sister Madeleine, was probably the best-known sportswear designer at the time. Swimwear could also be found in the Cannes boutiques of Lanvin, Molyneux, Schiaparelli and Poiret (Kennnedy 53).

The 1930s gave way to the health and fitness movement which favoured fit and healthy female physiques. To maintain their figures, women were encouraged to participate in exercise, though only in ways that were deemed lady-like. Swimming was one of these exercises, which also gave women the opportunity to experiment with tanning. Towards the end of the 1920s, tanned skin was no longer a marker of the working class, but instead became fashionable and conveyed that one holidayed, and was therefore affluent. So much so, in 1932, Elsa Schiaparelli patented a backless swimsuit with a built-in brassiere for the sole purpose of avoiding tan lines from swimsuit straps whilst sunbathing (Snodgrass 566).

The boyish silhouettes were a thing of the past as women sought more shapely figures. The swimsuit in figure 9 is a machine-knit, woollen garment from 1937. Wool was favoured for its slightly elasticated qualities. The swimsuit has thin straps allowing women to catch the sun on their shoulders. There is a ribbed midriff panel which would have provided extra support and enhanced the female figure. The brief-like bottoms maintain the wearer’s modesty.

1945-1999

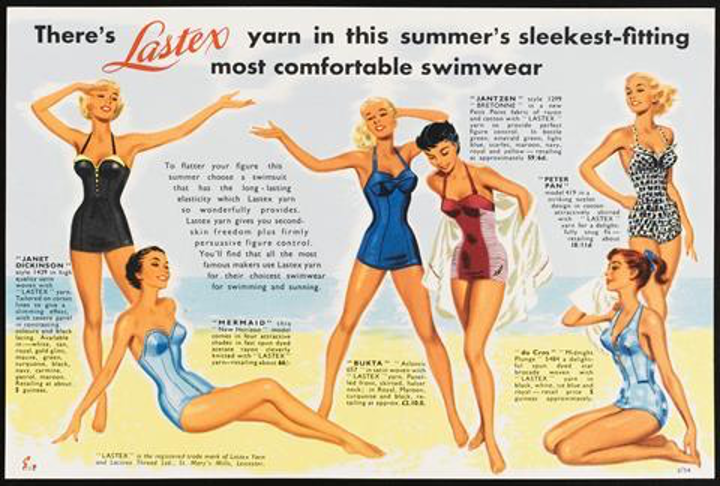

Lastex yarn (Fig. 10) was invented in 1931 (Kennedy 71). This was a game changer for swimwear once it was regularly used in production. Typically knitted swimsuits were made from wool which would lose its shape when wet. The introduction of Lastex yarn into women’s swimwear meant the garments would hold their form in and out of the water. Lastex would often be combined with artificial fibres such as rayon resulting in a stretchy and shiny fabric (Kennedy 71). Swimsuits could now be produced in a much larger range of colours and prints (Kennedy 71). Furthermore, at the end of the 1940s, Christian Dior launched his New Look which consisted of nipped in waists and full skirts, accentuating the female form. This exciting design shifted the trend to feminine and hourglass figures for women, including in swimwear. In this Lastex yarn advertisement from ca. 1950 (Fig. 10), the figure-hugging swimsuits reflect the fashionable feminine post-war silhouettes.

One of the most significant moments in the history of women’s swimwear was the creation of the bikini in 1946. The design of the bikini is credited to two separate designers who introduced the revolutionary garment at the same time. Jacques Heim, a French fashion designer, created a minimalist two-piece swimming garment in May 1946, called the Atome. Heim’s Atome featured a bra-like top and bottoms which covered the bottom and navel. Later that year, in July 1946, Louis Réard, an engineer turned designer, created what he called the bikini. Réard’s skimpy design, pictured in figure 11, consisted of only four triangles of material that were held together with string. The two designs competed for public attention and whilst Heim’s garment was the first to be worn on a beach, it was the term bikini, as coined by Réard, that stuck.

The rise of the film industry and Hollywood glamour, which celebrated the female form in its entirety, had a big impact on the swimwear industry. In 1952, Bridget Bardot starred in the French film Manina, The Girl in the Bikini. At just 17, Bardot was one of the first women to sport a bikini on the big screen. Towards the end of the decade, in 1956, Bardot appeared bikini-clad again in And God Created Women. These appearances brought the bikini into mainstream media, thus beginning the garment’s transition from outrageous and shocking to everyday. According to Vogue, by the mid-1950s swimwear was seen more as a “state of dress, not undress” (Delis Hill 63), illustrating how liberated fashion trends were gradually being accepted, even if society was not quite ready for the bikini.

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown. Before the bikini: ‘To flatter your figure this summer choose a swimsuit that has the long-lasting elasticity which Lastex yarn provides…’, ca. 1950s. Source: Alamy Stock Photos

Fig. 11 - Photographer unknown (French). Bikini At The Molitor Swimming Pool, 1946. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 12 - Willy Rozier (French, 1901-1983). Bridget Bardot, 1952, Manina, The Girl in the Bikini, with Jean-Francois Calve, Ullstein Bild Dtl, 1952. Source: Getty Images

In terms of competitive swimming, Speedo first introduced nylon into swimwear in 1956 (Kennedy 10). For the Melbourne Olympics in 1956, Speedo created the well-known male Speedo shorts (Kennedy 10). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the technological advances in materiality were prioritised for use in male competitive swimming before female competitive swimming. However, it was not long before women’s competitive swimwear also utilised the hydrodynamic qualities of nylon. In the 1970s Speedo introduced elastane into their swimwear. The combination of elastane and nylon significantly reduced water drag and improved the durability of swimwear.

Fig. 13 - Rudi Gernreich (American, born Austria, 1922–1985). Bathing Suit, 1964. Wool, elastic. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986.517.13. Gift of Betty Furness, 1986. Source: The Met

Fig. 14 - William Claxton (American, 1927-2008). Peggy Moffit, monokini by Rudi Gernreich, 1964. Source: Feature Shoot

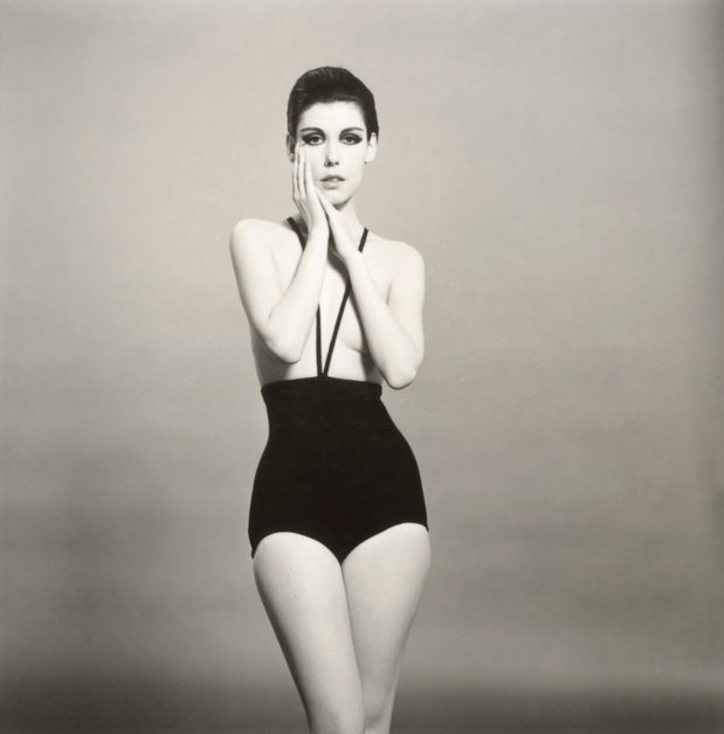

Designers continued to experiment with swimwear throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Emanuel Ungaro, André Courrѐges, Giorgio Armani, Oscar de la Renta and Calvin Klein all started selling ready-to-wear swimwear in the 1960s (Snodgrass 567). In 1964, the designer Rudi Gernreich launched his iconic monokini (Figs. 13-14). The first topless garment, the one-piece consisted of slim-fitting high-waisted bottoms which were held in place by thin halter-neck straps. Gernreich’s monokini thus juxtaposed conservative dress with immodesty.

Fig. 15 - Photographer unknown. Nicolette Sheridan at the 1988 Kauai Lagoons Celebrity Sports Invitational, 1988. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 16 - Photographer unknown. Pamela Anderson, Baywatch, 1995. Source: Harper's Bazaar

Towards the end of the twentieth-century, women’s swimwear became increasingly bold and colourful, a reflection of the fashion trends at the time. Bikinis and swimsuits were still the go-to swimwear, which now featured high-cut legs, strapless bandeau bikini tops and even matching sarongs (Fig. 15). The television show Baywatch, which first aired in 1989, became known for its characters’ bright red, high-cut swimsuits (Fig. 16). This style of swimwear re-popularised the one-piece in this new shape.

21st Century

Competitive swimming in the twenty-first century has continued to benefit from technological advancements in shapes and materials. In 2008 Speedo launched the LZR Racer, pictured in figures 17 and 18. The body-length swimsuit is made from elastane-nylon and polyurethane. These swimsuits were controversial as many felt the materials being used gave an unfair advantage due to their hydrodynamic properties. Following their use in the 2008 Beijing Olympics, where athletes who wore the LZR performed exceptionally well, the regulations for swimwear in the Olympic games were revised. It was concluded that women’s swimwear could only be shoulder to knee-length.

Since the 2000s, many female swimwear trends from the twentieth century are being revisited due to the cyclical nature of fashion. 1950s one-pieces, high-cut Baywatch swimwear and itsy-bitsy teeny-weeny bikinis will often be spotted on the same beach. Women’s swimwear continues to be more than just a functional garment, it must also be fashionable. Something that is new in female swimwear in the twenty-first century is swimwear brands being more inclusive of female sizing. The pressure to look a certain way when poolside is slowly dwindling. Whilst the twentieth-century sought to eradicate laws controlling women’s modesty, perhaps the twenty-first century will be the era when women’s swimwear becomes inclusive for all.

Fig. 17 - Photographer unknown. Speedo Launch Worlds Fastest Swimsuit, 2008. Source: Getty Images

Fig. 18 - Mike Stobe (American). Speedo Swimsuit Launch, 2008. Source: Getty Images

References:

- Delis Hill, Daniel. As Seen in Vogue. Texas: Texas Tech University Press. 2007. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1027144384

- Kay, Fiona and Storey, Neil. R. 1940s Fashion. England: Amberley Publishing, 2018. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/100792685

- Kennedy, Sarah. Vintage Swimwear: A History of Twentieth Century Fashions. London: Carlton. 2010. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1089738980

- Kidwell, Claudia Brush. Women’s Bathing and Swimming Costume in the United States. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. 1968. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/249672621

- Schmidt, Christine and Tay, Jinna. Undressing Kellerman, Uncovering Broadhurst: The Modern Women and “Un-Australia”, Fashion Theory, Volume 13, Issue 4. https://doi.org/10.2752/175174109X467495

- Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. World Clothing and Fashion: An Encyclopaedia of History, Culture and Social Influence. London, England: Routledge. 2014. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/881384673