This essay traces the evolution of New York’s shopping scene in the 19th century from the downtown dry goods store to the uptown “palace of consumption.” Read Part 1 here.

By the late 1850s the Grand Street area was established as the new shopping district, but society had already moved north to live. Nathaniel P. Willis, editor of The Home Journal, described the smart set as those:

“who keep carriages, live above Bleecker Street, are subscribers to the opera, go to Grace Church, have a town house and country house, [and] give balls and parties.”

A.T. Stewart, always ahead of the game, moved his store in 1862 into a cast iron palace on Broadway between Ninth and Tenth Streets. Fully embracing the industrial age, A.T. Stewart bid farewell not only to lower Manhattan, but also to the marble of his former palace. Outside, cast iron formed an elaborate and fashionable façade while inside cast iron columns supported the building, enabling open spaces to become the distinctive department store architecture. The large open interiors, washed with natural light from the great glass dome, embodied the new style of consumption— drawing in crowds of shoppers who were free to leisurely study the vast array of local and imported merchandise.

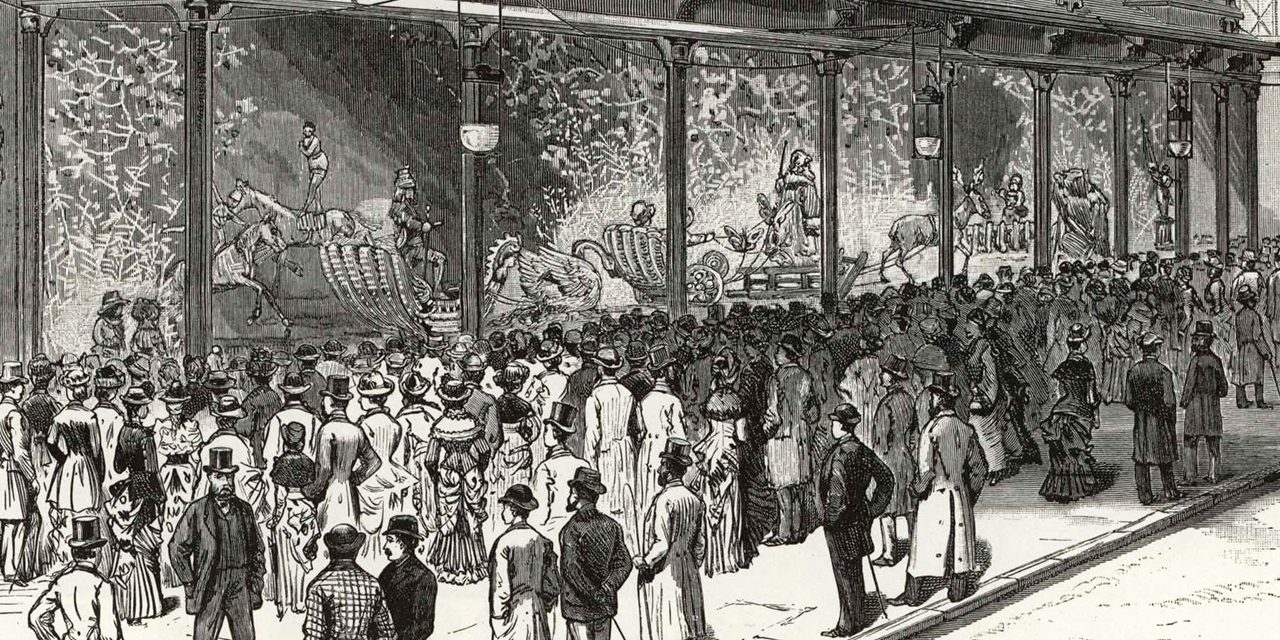

Fig. 1 - Artist unknown. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, Christmas shopping on Grand Street, New York, 1890. Source: Wikimedia

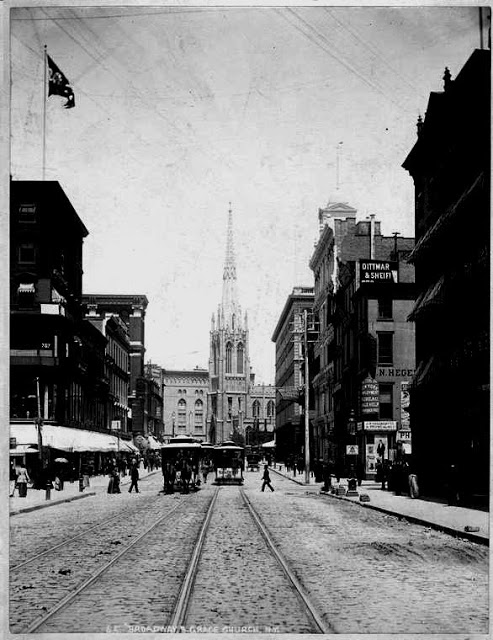

Fig. 2 - J. S. Johnston. Broadway & Grace Church, N.Y.. New York: Art and Picture Collection, 800598. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections

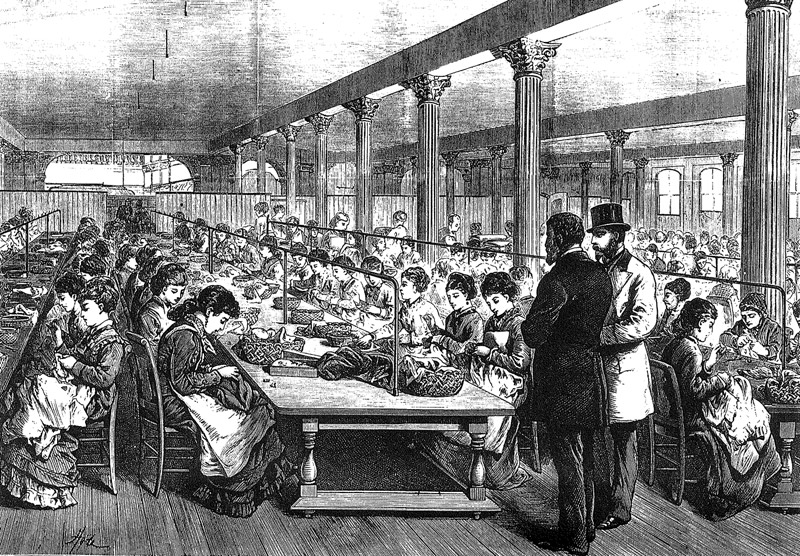

A.T. Stewart’s eight-floored fashion emporium employed over 2,000 men and women. One visitor observed that this immense establishment was arranged as follows:

“There is one general superintendent, with nineteen assistants, each of whom is the head of a department. Nine cashiers receive and pay out money, twenty- five book keepers keep the record of the day; thirty ushers direct purchasers to the department they seek; two hundred cash boys receive the money and bring back the change of purchases; four hundred and seventy clerks, a few of whom are females, make the sales of the day; fifty porters do the heavy work and nine hundred seamstresses are employed in the manufacturing department. Besides these, there are usually about five hundred other persons employed about the establishment in various capacities.”

This account demonstrates that the traditional dry goods store has fully bloomed into a department store, providing employment to many and a substantial income to some.

The 1860s gave birth to New York’s most famous shopping district—the “Ladies Mile.” Historians define the Ladies Mile as a stretch of blocks from Fourteenth to Twenty Third Streets along Broadway and Sixth Avenue and later up Fifth Avenue. As the city’s elite society started another migration northward, now residing around Union and Madison Squares, store owners felt compelled to follow.

Though A.T. Stewart remained successful in its Ninth Street location, most downtown establishments that made the move to Grand Street area in the 1850s, relocated further north to the Ladies Mile in the 1860s. The stores enjoyed a constant traffic of shoppers who were transported to the area in carriages and public horse drawn trolleys from every direction–up and down Broadway and from the two rivers.

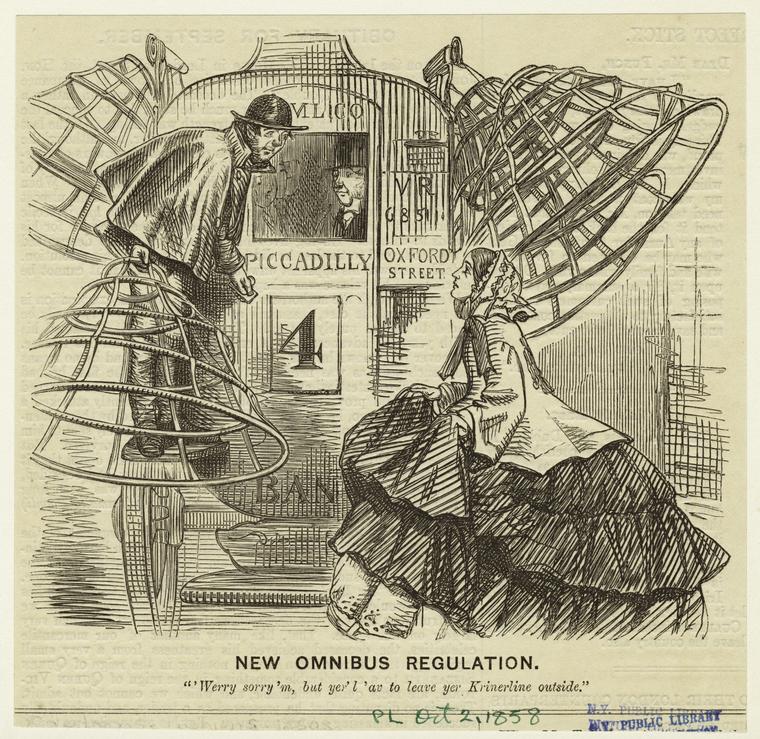

If boarding a carriage was challenging with the fashionable clothes of the 1850s, it must have been as hard, if not harder, when in the 1860s the horsehair crinoline gave way to a new invention. The cage crinoline, a petticoat of flexible steel hoops, invented in 1856, was mass-produced in factories and sold ready-made in the department stores built of the same material. The lightweight steel supported even the widest skirt, freeing women from the cumbersome weight of the petticoats, yet allowing skirts to achieve an even wider circumference. The increasing use of sewing machine, invented in the late 1840s, meant that elaborate trims were more easily applied to dresses. Decorations such as machine-made lace, embroidery and ribbons were now more affordable, permitting even women of lesser income to participate in fashion.

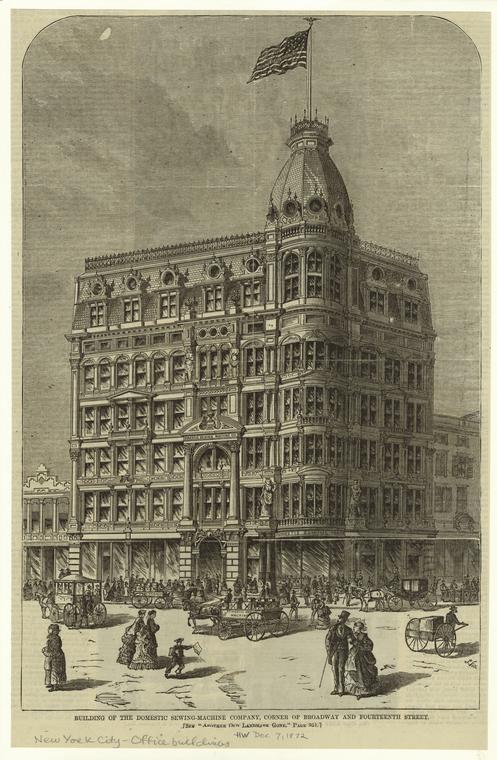

The invention of the sewing machine is largely credited for propelling the dry goods trade along Ladies Mile, not only for its ability to increase production, but also because it became available for domestic use. Union Square and the surrounding area of Ladies Mile was also becoming a center for the selling and promoting of domestic sewing machines. The most famous was the Domestic Sewing Machine building, where fashion shows displayed imported dress models from Europe. These models were later translated into paper patterns published and sold in the company’s Fashion Review magazine. The paper patterns would have been taken to a local dress-maker, several of them residing along the ladies mile, or cut and sewn at home. The fabric, trims, undergarments and accessories to go with the dress would have been offered and religiously purchased at the new palaces of consumption- the grand department stores.

Fig. 3 - Wurts Bros.. A.T. Stewart’s store at the corner of Broadway and Tenth Street, ca. 1869. New York: The New York Public Library, AZ 06-6805. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Fig. 4 - Artist unknown. The sewing-room at A.T. Stewart's, between Ninth and Tenth Streets, Broadway and Fourth Avenue / Hyde, 1875. Wood engraving. Washington: The Library of Congress, Illus. in AP2.L52 1875 Case Y. Purchase, The Lauder Foundation and The Irving Penn Foundation Gifts, 2014. Source: Library of Congress

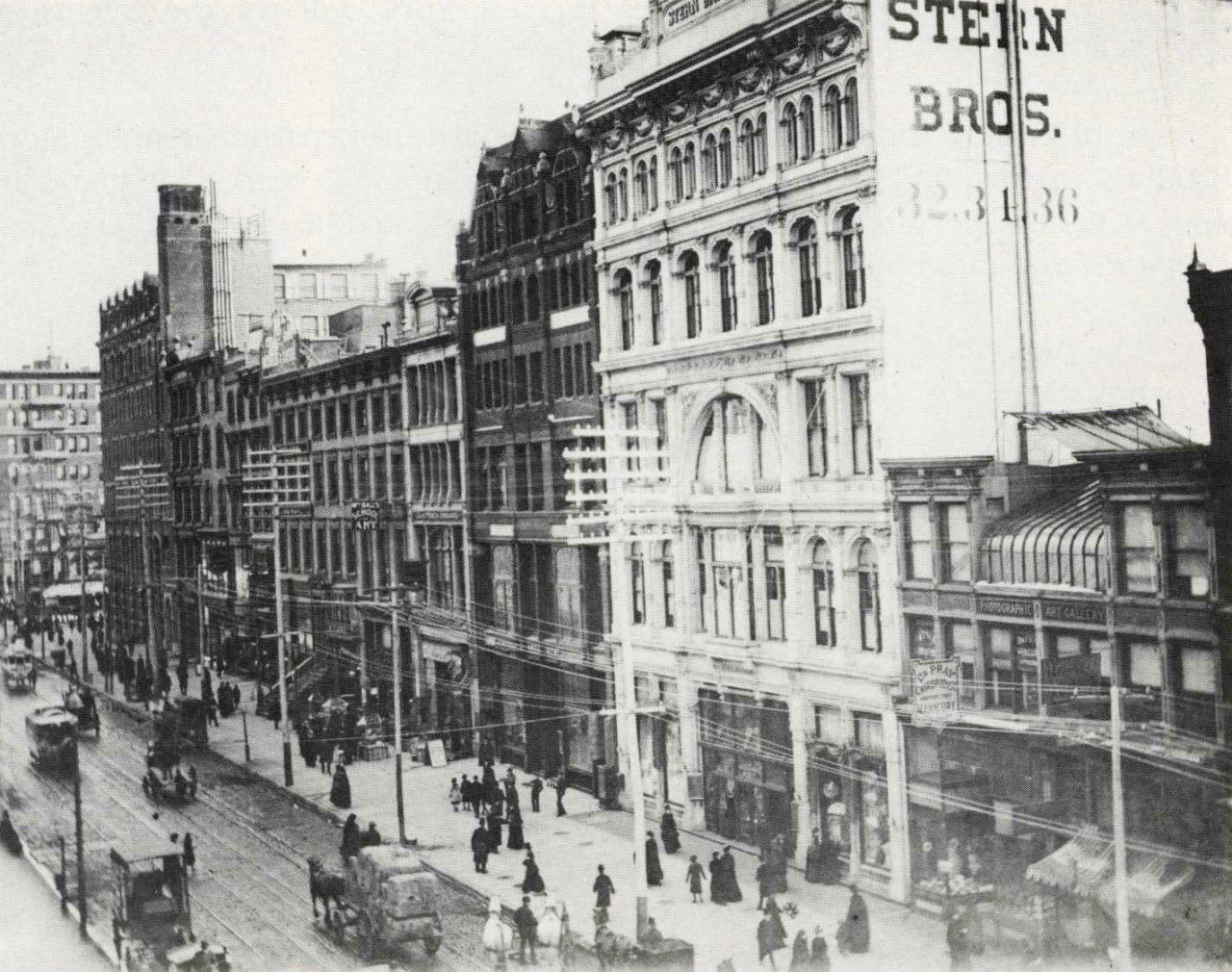

Fig. 5 - Artist unknown. Twenty Third Street, 1885. Source: On Pins and Needles

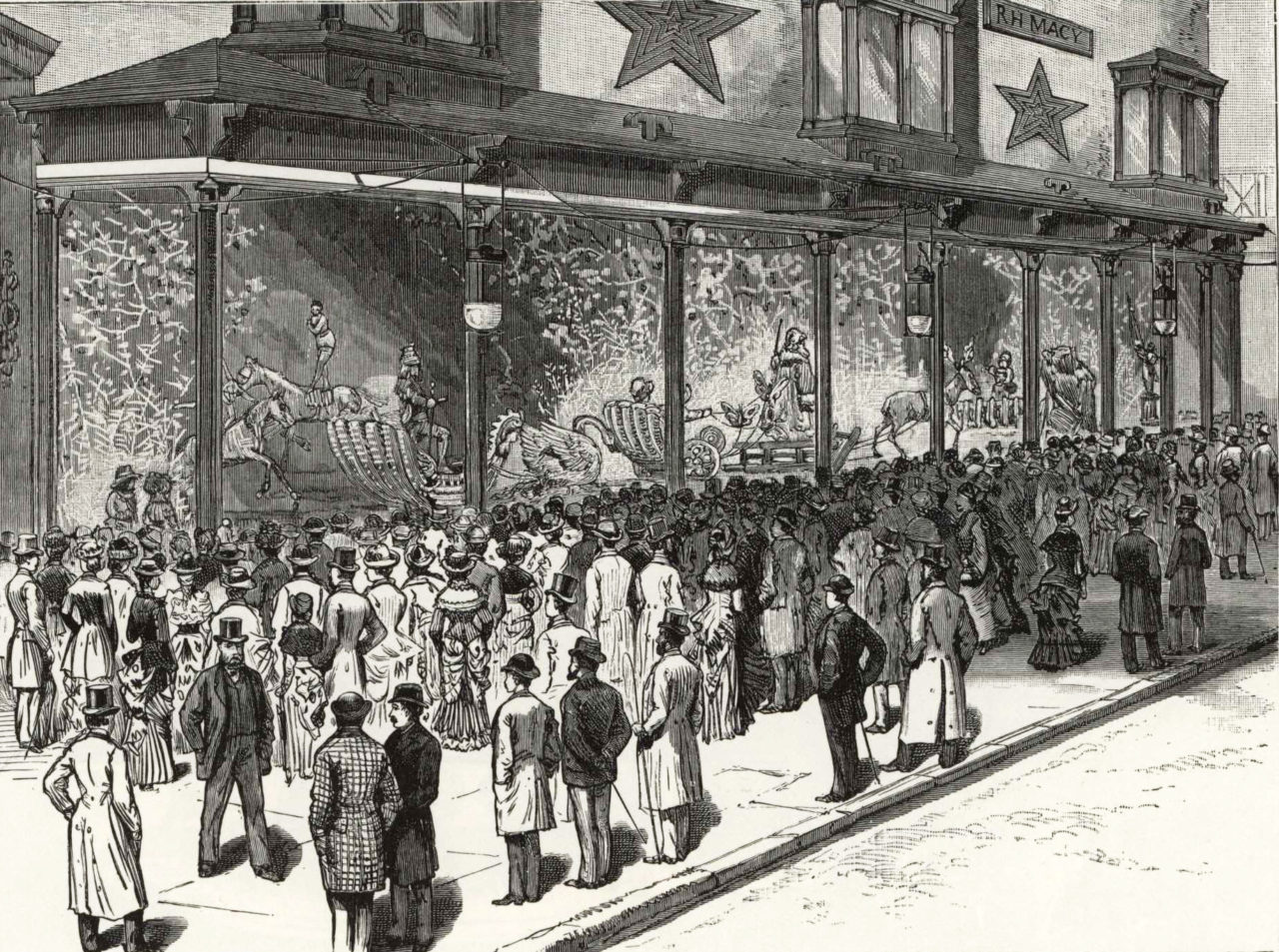

Although department store owners chased elite society, leaping from one district to another in an attempt to remain close to the trendsetters, it is evident that by the 1860s the new commercial palaces catered no less to the rising middle classes. Fashion, so it seems, was democratized by technological advances. The department store adopted several marketing methods to appeal to all classes, yet the newest of them all was the window display. For the nineteenth-century shopper, window displays created a sensation. Presenting the goods behind a glass window for the shoppers’ scrutinizing eyes, was in many ways an extension of the mind-set of the open space interior, which allowed visitors to roam the sales floor uninterrupted. This new approach to shopping made luxury goods seem more accessible to more people. The German historian Uwe Spiekermann notes that “when gazing into the shop window, even a person with little income believed that the world was at his feet.”

Fig. 6 - Maker unknown (English). Cage crinoline, 1871. Spring-steel and linen. London: The Victoria and Albert Museum, T.195-1984. Given by Miss C. E. and Miss E. C. Edlmann. Source: The V&A Museum

Fig. 7 - Artist unknown. New Omnibus Regulation, 1858. New York: New York Public Library, PC COSTU-Car-18. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections

As America entered the Gilded Age, the middle and upper classes’ appetite for consuming fashion grew even more. Store owners who survived the panic of 1873 could not expand fast enough to appease this hunger. Barely surviving the economic downturn, Lord & Taylor recovered and continued growing, gradually adding more and more buildings along Nineteenth and Twentieth Streets, eventually taking up the whole block. But, by the turn of the century, society had set in motion yet another cycle of migration northward.

As commerce came in place of elite residence, the once fashionable districts of Union and Madison Squares were abandoned for the new, more desirable neighborhoods, which lay above 32nd street up to the edge of Central Park. While American millionaires lived in private palaces along Fifth Avenue, the middle class had the department store. By the end of the decade most major Ladies Mile department stores adopted a new Fifth Avenue address which epitomized the luxury and wealth most associated with the Industrial Revolution. For the masses visiting Lord & Taylor, B. Altman’s, Henri Bendel, and Arnold Constable among others who had found a new home here, the commercial palace became a symbol of potential social mobility, attained by the mass consumption of luxury goods.

Fig. 8 - Designer unknown. Two-piece dress, ca. 1859. Silk ottoman and silk velvet. New York: The Museum at FIT, P91.23.3. Source: The Museum at FIT

Fig. 9 - Stanley Fox. Building of the Domestic Sewing-Machine Company, corner of Broadway and Fourteenth Street, 1872. Wood block print; 37 x 24 cm (14 1/2 x 9 1/2 in). New York: New York Public Library, PC NEW YC-Off. Source: The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Fig. 10 - Artist unknown. An early rendering of an animated display at R.H. Macy’s in New York City, ca. 1884. Source: Collectors Weekly

References:

- Birmingham, Nan Tillson. Store: A Memoir of America’s Greatest Department Stores. New York: Putnam, 1978. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/918392031.

- Boyer, M. Christine. Manhattan Manners: Architecture and Style, 1850-1900. New York: Rizoli, 1985. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/12344148.

- Font, Lourdes M., and Trudie Grace. Summer Afternoon: Fashion and Leisure in the Hudson Highlands, 1850-1950. Cold Spring, NY: Putnam History Museum, 2012. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/827732342.

- Hendrickson, Robert. The Grand Emporiums: The Illustrated History of America’s Great Department Stores. New York: Stein and Day, 1980. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/11476450.

- The History of Lord & Taylor, 1826-1926. New York: [Guinn], 1926. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/101652433.

- Morris, Lloyd R. Incredible New York: High Life and Low Life from 1850 to 1950, 1996. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1024107303.

- Weisman, Winston. “Commercial Palaces of New York: 1845-1875.” The Art Bulletin 36, no. 4 (1954): 285–302. https://doi.org/10.2307/3047580.

- Whitaker, Jan. The World of Department Stores. New York: Vendome Press, 2011. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/818618320.